Tetrahymena

| Tetrahymena | |

|---|---|

| |

| Tetrahymena thermophila | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| (unranked): | SAR |

| (unranked): | Alveolata |

| Phylum: | Ciliophora |

| Class: | Oligohymenophorea |

| Order: | Hymenostomatida |

| Family: | Tetrahymenidae |

| Genus: | Tetrahymena |

| Species | |

|

T. hegewischi | |

Tetrahymena are free-living ciliate protozoa that can also switch from commensalistic to pathogenic modes of survival. They are common in freshwater ponds. Tetrahymena species used as model organisms in biomedical research are T. thermophila and T. pyriformis.[1]

T. thermophila: a model organism in experimental biology

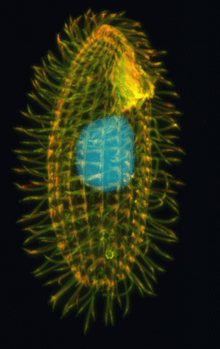

As a ciliated protozoan, Tetrahymena thermophila exhibits nuclear dimorphism: two types of cell nuclei. They have a bigger, non-germline macronucleus and a small, germline micronucleus in each cell at the same time and they both carry out different functions with distinct cytological and biological properties. This unique versatility allows scientists to use Tetrahymena to identify several key factors regarding gene expression and genome integrity. In addition, Tetrahymena possess hundreds of cilia and has complicated microtubule structures, making it an optimal model to illustrate the diversity and functions of microtubule arrays.

Because Tetrahymena can be grown in a large quantity in the laboratory with ease, it has been a great source for biochemical analysis for years, specifically for enzymatic activities and purification of sub-cellular components. In addition, with the advancement of genetic techniques it has become an excellent model to study the gene function in vivo. The recent sequencing of the macronucleus genome should ensure that Tetrahymena will be continuously used as a model system.

Tetrahymena thermophila exists in 7 different sexes (mating types) that can reproduce in 21 different combinations, and a single tetrahymena cannot reproduce sexually with itself. Each organism "decides" which sex it will become during mating, through a stochastic process.[2]

Studies on Tetrahymena have contributed to several scientific milestones including:

- First cell which showed synchronized division, which led to the first insights into the existence of mechanisms which control the cell cycle.[3]

- Identification and purification of the first cytoskeleton based motor protein such as dynein.[3]

- Aid in the discovery of lysosomes and peroxisomes.[3]

- Early molecular identification of somatic genome rearrangement.[3]

- Discovery of the molecular structure of telomeres, telomerase enzyme, the templating role of telomerase RNA and their roles in cellular senescence and chromosome healing (for which a Nobel Prize was won).[3]

- Nobel Prize–winning co-discovery (1989, in Chemistry) of catalytic ribonucleic acid (ribozyme).[3]

- Discovery of the function of histone acetylation.[3]

- Demonstration of the roles of posttranslational modification such as acetylation and glycylation on tubulins and discovery of the enzymes responsible for some of these modifications (glutamylation)

- Crystal structure of 40S ribosome in complex with its initiation factor eIF1

- First demonstration that two of the "universal" stop codons, UAA and UAG, will code for the amino acid glutamine in some eukaryotes, leaving UGA as the only termination codon in these organisms.[4]

- Discovery of self-splicing RNA.[5]

Life cycle

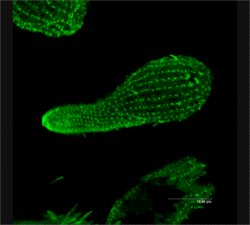

The life cycle of T. thermophila consists of an alternation between asexual and sexual stages. In nutrient rich media during vegetative growth cells reproduce asexually by binary fission. This type of cell division occurs by a sequence of morphogenetic events that results in the development of duplicate sets of cell structures, one for each daughter cell. Only during starvation conditions will cells commit to sexual conjugation, pairing and fusing with a cell of opposite mating type. Tetrahymena has seven mating types; each of which can mate with any of the other six without preference, but not its own.

Typical of ciliates, T. thermophila differentiates its genome into two functionally distinct types of nuclei, each specifically used during the two different stages of the life cycle. The diploid germline micronucleus is transcriptionally silent and only plays a role during sexual life stages. The germline nucleus contains 5 pairs of chromosomes which encode the heritable information passed down from one sexual generation to the next. During sexual conjugation, haploid micronuclear meiotic products from both parental cells fuse, leading to the creation of a new micro- and macronucleus

in progeny cells. Sexual conjugation occurs when cells starved for at least 2hrs in a nutrient-depleted media encounter a cell of complementary mating type. After a brief period of co-stimulation (~1hr), starved cells begin to pair at their anterior ends to form a specialized region of membrane called the conjugation junction.

It is at this junctional zone that several hundred fusion pores form, allowing for the mutual exchange of protein, RNA and eventually a meiotic product of their micronucleus. This whole process takes about 12 hours at 30 °C, but even longer than this at cooler temperatures. The sequence of events during conjugation is outlined in the accompanying figure.[6]

The larger polyploid macronucleus is transcriptionally active, meaning its genes are actively expressed, and so it controls somatic cell functions during vegetative growth. The polyploid nature of the macronucleus refers to the fact that it contains approximately 200–300 autonomously replicating linear DNA mini-chromosomes. These minichromosomes have their own telomeres and are derived via site-specific fragmentation of the five original micronuclear chromosomes during sexual development. In T. thermophila each of these minichromosomes encodes multiple genes and exists at a copy number of approximately 45-50 within the macronucleus. The exception to this is the minichromosome encoding the rDNA, which is massively upregulated, existing at a copy number of approximately 10,000 within the macronucleus. Because the macronucleus divides amitotically during binary fission, these minichromosomes are un-equally divided between the clonal daughter cells. Through natural or artificial selection, this method of DNA partitioning in the somatic genome can lead to clonal cell lines with different macronuclear phenotypes fixed for a particular trait, in a process called phenotypic assortment. In this way, the polyploid genome can fine-tune its adaptation to environmental conditions through gain of beneficial mutations on any given mini-chromosome whose replication is then selected for, or conversely, loss of a minichromosome which accrues a negative mutation. However, the macronucleus is only propagated from one cell to the next during the asexual, vegetative stage of the life cycle, and so it is never directly inherited by sexual progeny. Only beneficial mutations that occur in the germline micronucleus of T. thermophila are passed down between generations, but these mutations would never be selected for environmentally in the parental cells because they are not expressed.[7]

DNA Repair

It is common among protists that the sexual cycle is inducible by stressful conditions such as starvation.[8] Such conditions often cause DNA damage. A central feature of meiosis is homologous recombination between non-sister chromosomes. In T. thermophila this process of meiotic recombination may be beneficial for repairing DNA damages caused by starvation.

Exposure of T. thermophila to UV light resulted in a greater than 100-fold increase in Rad51 gene expression.[9] Treatment with the DNA alkylating agent methyl methane sulfonate also resulted in substantially elevated Rad 51 protein levels. These findings suggest that ciliates such as T. thermophila utilize a Rad51-dependent recombinational pathway to repair damaged DNA.

The Rad51 recombinase of T. thermophila is a homolog of the Escherichia coli RecA recombinase. In T. thermophila, Rad51 participates in homologous recombination during mitosis, meiosis and in the repair of double-strand breaks.[10] During conjugation, Rad51 is necessary for completion of meiosis. Meiosis in T. thermophila appears to employ a Mus81-dependent pathway that does not use a synaptonemal complex and is considered secondary in most other model eukaryotes.[11] This pathway includes the Mus81 resolvase and the Sgs1 helicase. The Sgs1 helicase appears to promote the non-crossover outcome of meiotic recombinational repair of DNA,[12] a pathway that generates little genetic variation.

References

- ↑ Elliott, Alfred M. (1973). Biology of Tetrahymena. Dowen, Hutchinson and Ross Inc. ISBN 0-87933-013-9.

- ↑ Selecting; Segment Joining, Gene; Deletion; Cervantes, MD; Hamilton, EP; Xiong, J; Lawson, MJ; Yuan, D; et al. (2013). "Selecting One of Several Mating Types through Gene Segment Joining and Deletion in Tetrahymena thermophila". PLoS Biol. 11 (3): e1001518. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001518.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Tetrahymena Genome Sequencing White Paper

- ↑ Horowitz S; Gorovsky M (April 1985). "An unusual genetic code in nuclear genes of Tetrahymena". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 82 (8): 2452–2455. doi:10.1073/pnas.82.8.2452. PMC 397576

. PMID 3921962.

. PMID 3921962. - ↑ Kruger, K.; Grabowski, P. J.; Zaug, A. J.; Sands, J.; Gottschling, D. E.; Cech, T. R. (1982). "Self-splicing RNA: Autoexcision and autocyclization of the ribosomal RNA intervening sequence of tetrahymena". Cell. 31: 147–57. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(82)90414-7. PMID 6297745.

- ↑ Elliott, AM; Hayes, RE (1953). "Mating Types in Tetrahymena". Biological Bulletin. 105: 269–284. doi:10.2307/1538642.

- ↑ Prescott DM (June 1994). "The DNA of ciliated protozoa". Microbiol. Rev. 58 (2): 233–67. PMC 372963

. PMID 8078435.

. PMID 8078435. - ↑ Bernstein, Harris; Bernstein, Carol; Michod, Richard E. (2011). "19. Meiosis as an Evolutionary Adaptation for DNA Repair". In Inna Kruman. DNA Repair. InTech Open Publisher. doi:10.5772/25117.

- ↑ Campbell C, Romero DP (1998). "Identification and characterization of the RAD51 gene from the ciliate Tetrahymena thermophila". Nucleic Acids Res. 26 (13): 3165–72. doi:10.1093/nar/26.13.3165. PMC 147671

. PMID 9628914.

. PMID 9628914. - ↑ Marsh, TC; Cole, ES; Stuart, KR; Campbell, C; Romero, DP (2000). "RAD51 is required for propagation of the germinal nucleus in Tetrahymena thermophila". Genetics. 154 (4): 1587–1596. PMID 10747055.

- ↑ Chi, J; Mahé, F; Loidl, J; Logsdon, J; Dunthorn, M (2014). "Meiosis gene inventory of four ciliates reveals the prevalence of a synaptonemal complex-independent crossover pathway". Mol Biol Evol. 31 (3): 660–672. doi:10.1093/molbev/mst258. PMID 24336924.

- ↑ Lukaszewicz A, Howard-Till RA, Loidl J (November 2013). "Mus81 nuclease and Sgs1 helicase are essential for meiotic recombination in a protist lacking a synaptonemal complex". Nucleic Acids Res. 41 (20): 9296–309. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt703. PMC 3814389

. PMID 23935123.

. PMID 23935123.

Further reading

- Methods in Cell Biology Volume 62: Tetrahymena thermophila, Edited by David J. Asai and James D. Forney. (2000). By Academic Press

ISBN 0-12-544164-9

- Collins, K.; Gorovsky, M.A. (2005). "Tetrahymena thermophila 5004392". Curr Biol. 15: R317–8. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.04.039.

- Eisen, JA; Coyne, RS; Wu, M; Wu, D; Thiagarajan, M; et al. (2006). "Macronuclear Genome Sequence of the Ciliate Tetrahymena thermophila, a Model Eukaryote". PLoS Biol. 4 (9): e286. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040286. PMC 1557398

. PMID 16933976.

. PMID 16933976.

External links

- Tetrahymena Stock Center at Cornell University

- ASSET: Advancing Secondary Science Education thru Tetrahymena

- Tetrahymena Genome Database

- Biogeography and Biodiversity of Tetrahymena

- Tetrahymena thermophila Genome Project at The Institute for Genomic Research

- Tetrahymena thermophila Genome Sequence Synopsis

- Tetrahymena thermophila genome paper

- Tetrahymena experiments on Journal of Visualized Experiments (JoVE) website

- Microbial Digital Specimen Archives: Tetrahymena image gallery

- All Creatures Great and Small: Elizabeth Blackburn