Dyatlov Pass incident

|

The group's tomb at the Mikhajlov Cemetry in Yekaterinburg. | |

| Native name | Гибель тургруппы Дятлова |

|---|---|

| Date | February 2, 1959 |

| Venue | Dyatlov Pass |

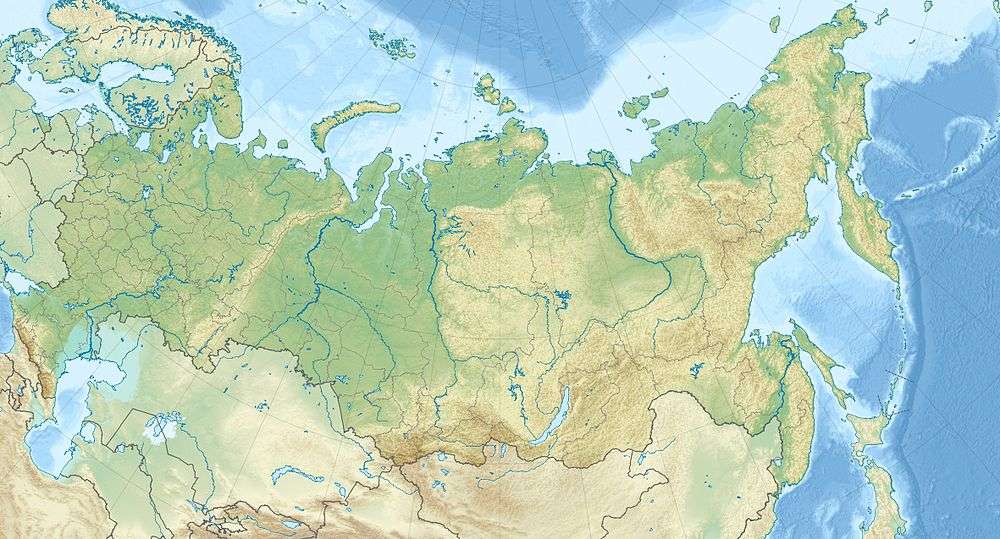

| Location | Kholat Syakhl, Northern Urals, Russia |

| Coordinates | 61°45′17″N 59°27′46″E / 61.75472°N 59.46278°ECoordinates: 61°45′17″N 59°27′46″E / 61.75472°N 59.46278°E |

| Type | Multiple deaths |

| Cause | Undetermined |

| Participants | Ski hikers from Ural Polytechnical Institute |

| Outcome | Area closed for three years |

| Deaths |

Nine dead from hypothermia and physical trauma |

The Dyatlov Pass incident (Russian: Гибель тургруппы Дятлова) is the mysterious deaths of nine ski hikers in the northern Ural Mountains on February 2, 1959. The experienced trekking group, who were all from the Ural Polytechnical Institute, had established a camp on the slopes of Kholat Syakhl when disaster struck. During the night something made them tear their way out of their tents from the inside and flee the campsite inadequately dressed in heavy snowfall and sub-zero temperatures.

Soviet investigators determined that six victims died from hypothermia but others showed signs of physical trauma. One victim had a fractured skull while another had brain damage but without any sign of distress to their skull. Additionally, a female team member had her tongue missing. The investigation concluded that an "unknown compelling force" had caused the deaths. Access to the region was consequently closed to amateur hikers and expeditions for three years after the incident (the area is named Dyatlov Pass in honor of the group's leader, Igor Dyatlov).

As the chronology of events remains uncertain due to the lack of survivors, several explanations have been put forward as to the cause; they include an animal attack, hypothermia, an avalanche, infrasound-induced panic, military involvement, or a combination of explanations.

Background

A group was formed for a ski trek across the northern Urals in Sverdlovsk Oblast. The original group, led by Igor Dyatlov, consisted of eight men and two women. Most were students or graduates of Ural Polytechnical Institute (Уральский политехнический институт, УПИ), now Ural Federal University:

- Igor Alekseievich Dyatlov (Игорь Алексеевич Дятлов), the group's leader, born January 13, 1936

- Yuri Nikolaievich Doroshenko (Юрий Николаевич Дорошенко), born January 29, 1938

- Lyudmila Alexandrovna Dubinina (Людмила Александровна Дубинина), born May 12, 1938

- Yuri (Georgiy) Alexeievich Krivonischenko (Юрий (Георгий) Алексеевич Кривонищенко), born February 7, 1935

- Alexander Sergeievich Kolevatov (Александр Сергеевич Колеватов), born November 16, 1934

- Zinaida Alekseevna Kolmogorova (Зинаида Алексеевна Колмогорова), born January 12, 1937

- Rustem Vladimirovich Slobodin (Рустем Владимирович Слободин), born January 11, 1936

- Nicolai Vladimirovich Thibeaux-Brignolles (Николай Владимирович Тибо-Бриньоль), born July 8, 1935

- Semyon (Alexander) Alekseevich Zolotariov (Семён (Александр) Алексеевич Золотарёв), born February 2, 1921

- Yuri Yefimovich Yudin (Юрий Ефимович Юдин), born July 19, 1937, died April 27, 2013[1]

The goal of the expedition was to reach Otorten (Отортен), a mountain 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) north of the site of the incident. This route, in February, was estimated as Category III, the most difficult. All members were experienced in long ski tours and mountain expeditions.

The group arrived by train at Ivdel (Ивдель), a city at the center of the northern province of Sverdlovsk Oblast on January 25. They then took a truck to Vizhai (Вижай) – the last inhabited settlement so far north. They started their march toward Otorten from Vizhai on January 27. The next day, one of the members, Yuri Yudin, was forced to go back due to illness.[2] The remaining group of nine people continued the trek.

Diaries and cameras found around their last campsite made it possible to track the group's route up to the day preceding the incident. On January 31, the group arrived at the edge of a highland area and began to prepare for climbing. In a wooded valley they cached surplus food and equipment that would be used for the trip back. The following day (February 1), the hikers started to move through the pass. It seems they planned to get over the pass and make camp for the next night on the opposite side, but because of worsening weather conditions – snowstorms and decreasing visibility – they lost their direction and deviated west, up towards the top of Kholat Syakhl. When they realized their mistake, the group decided to stop and set up camp there on the slope of the mountain, rather than moving 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi) downhill to a forested area which would have offered some shelter from the elements.[2] Yudin postulated that "Dyatlov probably did not want to lose the altitude they had gained, or he decided to practice camping on the mountain slope."[2]

Search and discovery

Before leaving, Dyatlov had agreed he would send a telegram to their sports club as soon as the group returned to Vizhai. It was expected that this would happen no later than February 12, but Dyatlov had told Yudin, before his departure from the group, that he expected to be longer. When the 12th passed and no messages had been received, there was no immediate reaction, as delays of a few days were common with such expeditions. It was not until the relatives of the travelers demanded a rescue operation on February 20 that the head of the institute sent the first rescue groups, consisting of volunteer students and teachers.[2] Later, the army and militsiya forces became involved, with planes and helicopters being ordered to join the rescue operation.

On February 26, the searchers found the group's abandoned and badly damaged tent on Kholat Syakhl. The campsite baffled the search party. Mikhail Sharavin, the student who found the tent, said "the tent was half torn down and covered with snow. It was empty, and all the group's belongings and shoes had been left behind."[2] Investigators said the tent had been cut open from inside. Eight or nine sets of footprints, left by people who were wearing only socks, a single shoe or were even barefoot, could be followed, leading down toward the edge of a nearby woods, on the opposite side of the pass, 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi) to the north-east. However, after 500 metres (1,600 ft) these tracks were covered with snow. At the forest's edge, under a large cedar, the searchers found the visible remains of a small fire, along with the first two bodies, those of Krivonischenko and Doroshenko, shoeless and dressed only in their underwear. The branches on the tree were broken up to five metres high, suggesting that one of the skiers had climbed up to look for something, perhaps the camp. Between the cedar and the camp the searchers found three more corpses: Dyatlov, Kolmogorova and Slobodin, who seemed to have died in poses suggesting that they were attempting to return to the tent.[2] They were found separately at distances of 300, 480 and 630 metres from the tree.

Searching for the remaining four travelers took more than two months. They were finally found on May 4 under four metres of snow in a ravine 75 metres farther into the woods from the cedar tree. These four were better dressed than the others, and there were signs that those who had died first had apparently relinquished their clothes to the others. Zolotariov was wearing Dubinina's faux fur coat and hat, while Dubinina's foot was wrapped in a piece of Krivonishenko's wool pants.

Another notable find besides the four remaining hikers was a camera around Zolotariov's neck. The camera was not reported as having been part of the equipment. Also, the film in the camera was reported to have been damaged by water.[3]

Investigation

A legal inquest started immediately after finding the first five bodies. A medical examination found no injuries which might have led to their deaths, and it was eventually concluded that they had all died of hypothermia. Slobodin had a small crack in his skull, but it was not thought to be a fatal wound.

An examination of the four bodies which were found in May shifted the narrative as to what had occurred during the incident. Three of the ski hikers had fatal injuries: Thibeaux-Brignolles had major skull damage, and both Dubinina and Zolotarev had major chest fractures. According to Dr. Boris Vozrozhdenny, the force required to cause such damage would have been extremely high, comparing it to the force of a car crash. Notably, the bodies had no external wounds related to the bone fractures, as if they had been subjected to a high level of pressure. However, major external injuries were found on Dubinina, who was missing her tongue, eyes, part of the lips, as well as facial tissue and a fragment of skullbone;[4] she also had extensive skin maceration on the hands. It was claimed that Dubinina was found lying face down in a small stream that ran under the snow and that her external injuries were in line with putrefaction in a wet environment, and were unlikely to be related to her death.

There was initial speculation that the indigenous Mansi people might have attacked and murdered the group for encroaching upon their lands, but investigation indicated that the nature of their deaths did not support this hypothesis; the hikers' footprints alone were visible, and they showed no sign of hand-to-hand struggle.[2]

Although the temperature was very low, around −25 to −30 °C (−13 to −22 °F) with a storm blowing, the dead were only partially dressed. Some of them had only one shoe, while others had no shoes or wore only socks.[2] Some were found wrapped in snips of ripped clothes that seemed to have been cut from those who were already dead.

Journalists reporting on the available parts of the inquest files claim that it states:

- Six of the group members died of hypothermia and three of fatal injuries.

- There were no indications of other people nearby on Kholat Syakhl apart from the nine travelers.

- The tent had been ripped open from within.

- The victims had died 6 to 8 hours after their last meal.

- Traces from the camp showed that all group members left the campsite of their own accord, on foot.

- To dispel the theory of an attack by the indigenous Mansi people, Dr. Boris Vozrozhdenny stated that the fatal injuries of the three bodies could not have been caused by another human being, "because the force of the blows had been too strong and no soft tissue had been damaged".[2]

- Forensic radiation tests had shown high doses of radioactive contamination on the clothes of a few victims.

- Released documents contained no information about the condition of the skiers' internal organs.

- There were no survivors of the incident.

At the time the verdict was that the group members all died because of a compelling natural force.[5] The inquest officially ceased in May 1959 as a result of the absence of a guilty party. The files were sent to a secret archive, and the photocopies of the case became available only in the 1990s, although some parts were missing.[2]

Controversy regarding investigation

- 12-year-old Yury Kuntsevich, who would later become head of the Yekaterinburg-based Dyatlov Foundation (see below), attended five of the hikers' funerals, and recalls their skin had a "deep brown tan".[2]

- Another group of hikers (about 50 kilometres south of the incident) reported that they saw strange orange spheres in the night sky to the north on the night of the incident.[2] Similar spheres were observed in Ivdel and adjacent areas continually during the period from February to March 1959, by various independent witnesses (including the meteorology service and the military).[2]

- Some reports suggest that there was a great deal of scrap metal in and around the area, leading to speculation that the military had utilized the area secretly.

Aftermath

In 1967, Sverdlovsk writer and journalist Yuri Yarovoi (Russian: Юрий Яровой) published the novel Of the Highest Degree of Complexity,[6] inspired by the incident. Yarovoi had been involved in the search for Dyatlov's group and at the inquest as an official photographer during both the search and the initial stage of the investigation, and so had insight into the events. The book was written during the Soviet era when details of the accident were kept secret and Yarovoi avoided revealing anything beyond the official position and well-known facts. The book romanticized the accident and had a much more optimistic end than the real events – only the group leader was found deceased. Yarovoi's colleagues say that he had alternative versions of the novel, but both were declined because of censorship. Since Yarovoi's death in 1980, all his archives, including photos, diaries and manuscripts, have been lost.

Anatoly Gushchin (Russian: Анатолий Гущин) summarized his research in the book The Price of State Secrets Is Nine Lives (Цена гостайны – девять жизней).[5] Some researchers criticized the novel due to its concentration on the speculative theory of a Soviet secret weapon experiment, but its publication led to public discussion, stimulated by interest in the paranormal. Indeed, many of those who had remained silent for thirty years reported new facts about the accident. One of them was the former police officer, Lev Ivanov (Лев Иванов), who led the official inquest in 1959. In 1990, he published an article which included his admission that the investigation team had no rational explanation for the accident. He also stated that, after his team reported that they had seen flying spheres, he then received direct orders from high-ranking regional officials to dismiss this claim.[7]

In 2000, a regional television company produced the documentary film The Mystery of Dyatlov Pass (Тайна перевала Дятлова). With the help of the film crew, a Yekaterinburg writer, Anna Matveyeva (Russian: Анна Матвеева), published a fiction/documentary novella of the same name.[8] A large part of the book includes broad quotations from the official case, diaries of victims, interviews with searchers and other documentaries collected by the film-makers. The narrative line of the book details the everyday life and thoughts of a modern woman (an alter ego of the author herself) who attempts to resolve the case.

Despite its fictional narrative, Matveyeva's book remains the largest source of documentary materials ever made available to the public regarding the incident. In addition, the pages of the case files and other documentaries (in photocopies and transcripts) are gradually being published on a web forum for enthusiastic researchers.[9]

A Dyatlov Foundation was founded in Yekaterinburg, with the help of Ural State Technical University, led by Yuri Kuntsevitch (Юрий Кунцевич). The foundation's stated aim is to convince current Russian officials to reopen the investigation of the case and to maintain the Dyatlov Museum to preserve the memory of the dead hikers.

Explanations

Avalanche

The theory that an avalanche caused the hikers' deaths, while initially popular, has since been questioned. Reviewing the sensationalist "Yeti" hypothesis (see below), American skeptic author Benjamin Radford suggests as more plausible;

"that the group woke up in a panic (...) and cut their way out the tent either because an avalanche had covered the entrance to their tent or because they were scared that an avalanche was imminent (...) (better to have a potentially repairable slit in a tent than risk being buried alive in it under tons of snow). They were poorly clothed because they had been sleeping, and ran to the safety of the nearby woods where trees would help slow oncoming snow. In the darkness of night they got separated into two or three groups; one group made a fire (hence the burned hands) while the others tried to return to the tent to recover their clothing, since the danger had apparently passed. But it was too cold, and they all froze to death before they could locate their tent in the darkness. At some point some of the clothes may have been recovered or swapped from the dead, but at any rate the group of four whose bodies were most severely damaged were caught in an avalanche and buried under 13 feet of snow (more than enough to account for the 'compelling natural force' the medical examiner described). Dubinina's tongue was likely removed by scavengers and ordinary predation."[10]

However, contrary to what Radford states, this is very unlikely, and evidence contradicting the avalanche theory includes:[11][12]

- The location of the incident did not have any obvious signs of an avalanche having taken place. An avalanche would have left certain patterns and debris distributed over a wide area. The bodies found within ten days of the event were covered with a very shallow layer of snow and, had there been an avalanche of sufficient strength to sweep away the second party, these bodies would have been swept away as well; this would have caused more serious and different injuries in the process and would have damaged the tree line.

- Over a hundred expeditions to the region were held since the incident, and none of them ever reported conditions that might create an avalanche. A study of the area using up-to-date terrain-related physics revealed that the location was entirely unlikely for such an avalanche to have occurred. The "dangerous conditions" found in another nearby area (which had significantly steeper slopes and cornices) were observed in April and May when the snowfalls of winter were melting. During February, when the incident occurred, there were no such conditions.

- An analysis of the terrain, the slope and the incline indicates that even if there could have been a very specific avalanche that circumvents the other criticisms, its trajectory would have bypassed the tent. It had collapsed laterally but not horizontally.

- Dyatlov was an experienced skier and the much older Alexander Zolotarev was studying for his Masters Certificate in ski instruction and mountain hiking. Neither of these two men would have been likely to camp anywhere in the path of a possible avalanche.

Infrasound

Another hypothesis popularized by Donnie Eichar's 2013 book Dead Mountain is that wind going around Holatchahl Mountain created a Kármán vortex street, which can produce infrasound capable of inducing panic attacks in humans.[13][14]

Military tests

Some people believe it was a military accident which was then covered up; there are records of parachute mines being tested by the Russian military in the area around the time the hikers were there. Parachute mines detonate a meter or two before they hit the ground and produce similar damage to those experienced by the hikers, heavy internal damage with very little external trauma. There were also glowing orbs reported in the sky in that general vicinity, possibly caused by such ordnance. This theory uses animals to account for the missing nose, tongue and leg of certain victims.[15] People believe the bodies were moved; photos of the tent show that it was apparently erected incorrectly, something that these experienced hikers are unlikely to have done.[16]

Paradoxical undressing

iScience Times posited that the hikers' deaths were caused by hypothermia, which can induce a behavior known as paradoxical undressing in which hypothermic subjects remove their clothes in response to perceived feelings of burning warmth.[17] That six out of nine hikers died of hypothermia is undisputed. The hypothesis doesn't address why the hikers fled the tent in the first place. The temperature inside the tent would not have been low enough to induce paradoxical undressing.

Cryptozoological explanation

The 2014 Discovery Channel special Russian Yeti: The Killer Lives explored the cryptozoology theory that the Dyatlov group was killed by a Russian yeti. Writer and skeptic, Benjamin Radford, wrote on the Doubtful News website that "Russian Yeti" begins with the premise that the injuries sustained by the skiers were so grave and extraordinary that they could only have been inflicted by an inhumanly strong creature."[18] The show focuses on Ludmila Dubinina's missing tongue and claims that something must have "ripped it out" of her. However, Radford states,

"As it happens a tongue-eating Yeti (…) is by far the least likely explanation. The 'missing parts' aspect of this case is a familiar one to skeptics, and has been invoked in countless other 'unsolved' mysteries including the chupacabra, cattle mutilations, Satanic animal sacrifices, and aliens. Typically a mystery is mongered by those unfamiliar with—or who intentionally ignore—ordinary predation and decomposition. Lots of animals both big and small scavenge on the soft parts of dead bodies. Another possibility is that Dubinina was caught in an avalanche and the force of the snow and rocks caused her tongue to be bitten off as she yelled and tumbled down the ravine where she was eventually found."[18]

He also thought the show:

"would have us believe that the nine skiers had an encounter with a Yeti, which they not only saw and photographed but stalked them. And yet none of the skiers mentioned anything else about the Yeti, or their shock at having photographed the creature. In fact, if [..] to be believed, their encounter with a Yeti was such an insignificant event that they didn't mention it at all in their journals, and continued their journey uninterrupted."[18]

The episode admits it found no real evidence to prove that the Yeti exists. However, the episode also states that one of the hikers did write in their journal "The snowman exists."

In popular culture

Popular interest in Russia was revived in the 1990s in the wake of Gushchin's 1990 novel, The Price of State Secrets Is Nine Lives. In 2000, a regional television company produced the documentary film, with a follow-up novella by Anna Matveyeva. Anna Kiryanova wrote a journal-style novel based on a fictionalized account of the incident in 2005.

The incident came to wider attention in popular media outside of Russia in the 2010s.

- Anatoly Guschin (Анатолий Гущин), The Price of State Secrets Is Nine Lives (Цена гостайны – девять жизней), 1990.

- The Mystery of Dyatlov Pass: 2000, TAU (Ural Television Agency).

- Матвеева Анна. Перевал Дятлова, 2000/1

- Кирьянова Анна. Охота Сорни-Най, 2005.

- The Greek author Panayiotis Panagopoulos transported the incident to the slopes of Mt. Olympus for his 2011 novel To Perasma tou Ignatiou (The Ignatius Pass).[19]

- A 2012 Episode of Dark Matters: Twisted But True tells the story of the incident.

- The Dyatlov Pass Incident (aka Devil's Pass), a film directed by Renny Harlin, was released on February 28, 2013 in Russia and Aug 23, 2013 in the USA. It follows five American students retracing the steps of the victims, but, being a work of fiction, makes several mistakes in describing the initial events, e.g. inverting names of victims.[20]

- The incident figures prominently in the 2012 novel City of Exiles by Alec Nevala-Lee.[21]

- The incident was featured on the Russian talk show Let Them Talk during a two-hour special in April 2013.

- The 2014 Discovery Channel special Russian Yeti: The Killer Lives explores the possibility that the hikers were killed by a Yeti.

- Russia's Mystery Files: Episode 2 – The Dyatlov Pass Incident, Nov 28, 2014, National Geographic[22]

- The 2015 Polish horror game Kholat is inspired by the Dead Mountain incident, in which the player goes to Dyatlov Pass in order to trace the steps of the lost expedition, and begins to uncover "the true cause" of the hikers' deaths.[23]

- In October 2015, the Russian metal band Kauan released their seventh full-length album Sorni Nai sung in poetic Finnish (the title references the golden goddess of the Ural Mountains' Mansi region). It is a concept album that focuses on the incident.

- The incident was the focus of an episode of the podcast Lore in July, 2016.[24]

- The event was the subject of an episode of The Last Podcast on The Left, in which the hosts theorize and extrapolate on the different theories and conspiracies surrounding the incident. [25]

- The incident is referred to in the Australian fiction TV series The Kettering Incident, supposedly being of the same origin as the mysterious events in Kettering.

References

- ↑ Дарья Кезина (27 April 2013). "Умер последний дятловец". Rossiyskaya Gazeta. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Osadchuk, Svetlana (February 19, 2008). "Mysterious Deaths of 9 Skiers Still Unresolved". St. Petersburg Times. Archived from the original on 28 February 2008. Retrieved 2016-01-22 – via CryptoZooNews, "Ural Mystery" posted by Loren Coleman.

- ↑ "The Cloaked Hedgehog". The Cloaked Hedgehog. Retrieved 2016-01-22.

- ↑ "Акт исследования трупа Дубининой - hibinaud". google.com.

- 1 2 Гущин Анатолий: Цена гостайны – девять жизней, изд-во "Уральский рабочий", Свердловск, 1990 (Gushchin Anatoly: The price of state secrets is nine lives, Izdatelstvo "Uralskyi Rabochyi", Sverdlovsk, 1990)

- ↑ 1967 (Yarovoi, Yuri: Of the Highest Degree of Complexity, Sredneuralskoye knizhnoye izdatelstvo, Sverdlovsk, 1967)

- ↑ Иванов Лев: "Тайна огненных шаров", "Ленинский путь", Кустанай, 22–24 ноября 1990 г. (Ivanov, Lev: "Enigma of the fire balls", Leninskyi Put, Kustanai, Nov 22–24 1990)

- ↑ Матвеева Анна: "Перевал Дятлова", "Урал" N12-2000, Екатеринбург (Matveyeva Anna: "Dyatlov pass", "Ural"#12-2000, Ekaterinburg)

- ↑ Перевал Дятлова: форум по исследованию гибели тургруппы И. Дятлова [Dyatlov Pass: Forum Research death Dyatlova tour group I]. Pereval 1959 (in Russian). RU: Forum 24. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

- ↑ Korbus, Jason; Nelson, Bobby. "SFR 291: The Russian Yeti of Dyatlov Pass w/ Benjamin Radford". Strange Frequency Radio. Archived from the original on 5 September 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ↑ "Dyatlov Pass – Some Answers". Curious World. Curious Britannia Ltd. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- ↑ Dunning, Brian. "Mystery at Dyatlov Pass". Skeptoid. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- ↑ Eichar, Donnie (2013). Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. pp. 246–2. ISBN 978-1-4521-2956-3.

- ↑ Zasky, Jason (February 1, 2014). "Return to Dead Mountain". Failure magazine. Retrieved 2014-06-29.

- ↑ "Dead Mountain: The Untold Story Of The Dyatlov Pass Incident." Publishers Weekly 260.32 (2013): 46. Business Source Elite. Web. 30 Oct. 2015.

- ↑ Nat Geo. "Russia's Mystery Files". National Geographic Wild. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- ↑ Smith, Anthony (1 August 2012). "Dyatlov Pass Explained: How Science Could Solve Russia's Most Terrifying Unsolved Mystery". isciencetimes.com

- 1 2 3 Radford, Benjamin. "Dyatlov Pass and Mass Murdering Yeti? A DN Exclusive". Doubtful News. Archived from the original on 9 September 2015. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ↑ The disappearance of the nine hikers.(Greek) Archived December 2, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Dyatlov Pass Incident, The". A Company Filmed Entertainment. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- ↑ "City of Exiles". Publishers Weekly. Retrieved February 2013. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "About Russia's Mystery Files Show – National Geographic Channel – UK". National Geographic Channel – Videos, TV Shows & Photos – UK.

- ↑ "Kholat – an adventure-horror game inspired by true event known as Dyatlov Pass Incident". kholat.com.

- ↑ "Episode 38: The Mountain". Retrieved 2016-07-12.

- ↑ http://cavecomedyradio.com/podcast-episode/episode152-the-dylatov-pass-incident/

Further reading

- McCloskey, Keith Journey to Dyatlov Pass: An Explanation of the Mystery (CreateSpace 24 October 2016, ISBN 978-1539583028)

- McCloskey, Keith Mountain of the Dead: The Dyatlov Pass Incident (The History Press Ltd, 1 July 2013, ISBN 978-0-7524-9148-6)

- Eichar, Donnie Dead Mountain: The True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident (Chronicle Books, October 22, 2013, ISBN 1-4521-1274-6)

- Irina Lobatcheva, Vladislav Lobatchev, Amanda Bosworth Dyatlov Pass Keeps Its Secret (Parallel Worlds' Books, August 30, 2013)

- Oss, Svetlana Don't Go There: The Mystery of Dyatlov Pass (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform Dec 2015 ISBN 978-1517755591)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dyatlov Pass incident. |

- Full investigation of the case including original documents, autopsy reports, morgue photos and detailed information on possible causes

- Map of the Dyatlov Pass region (sheet P-40-83,84) scale 1:100000 (Russian)

- Deathly Urals location draws in tourists

- Complete photo gallery including search party photos (Russian)

- Some photos and text (Russian)

- Photo gallery including: party photos, photos of some investigator's documents including termination of criminal case act (Russian)

- Mystery at Dyatlov Pass – A look at one of the most bizarre cases in Russian cross country skiing history Skeptoid: Critical Analysis of Pop Phenomena

- The Dyatlov Pass Accident

- Photo-video site with English

- Atlas Obscura article on the Dyatlov Pass Incident

- Death on the trail. Controlled delivery theory by A. Rakitin(Russian)