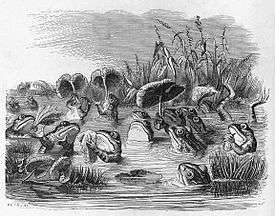

The Frogs and the Sun

The Frogs and the Sun is one of Aesop's Fables and is numbered 314 in the Perry Index.[1] It has been given political applications since Classical times.

The fable

There are both Greek and Latin versions of the fable. Babrius tells it unadorned and leaves hearers to draw their own conclusion, but Phaedrus gives the story a context. While people are rejoicing at the wedding of a thief, Aesop tells a story of frogs who lament at the marriage of the sun. This would mean the birth of a second sun and the frogs suffer already from the drying up of the ponds and marshes in which they live.

Though the story appears to have an ecological meaning, it was believed that the real target was Sejanus, the powerful aide of the Roman Emperor Tiberius, who had attempted to marry into the imperial family.[2] Certainly the fable was used in a similar way to criticize overweaning lords during the Middle Ages. Marie de France's Ysopet contains a version of the story which was to influence later writers. In her telling, the Sun asks the animals for advice on taking a partner. Alarmed, they appeal to Destiny on the grounds that nothing would be able to grow in the heat of a second sun. Marie draws the feudal lesson in a moralising passage at the end.[3]

The fable was included in Nicholas Bozon's collection of moralising stories (Contes moralisés) during the 1320s. Prefaced with a Latin comment that great lords impoverish others, it pictures the Sun asking his courtiers to find him a rich wife. They take the problem to Destiny, who points out the danger that would follow from having a second sun.[4] A century later, John Lydgate tells the story of "The Sun’s Marriage" in his Isopes Fabules. Here it is prefaced by an attack on tyranny, which the story is to illustrate. The Sun asks the assembly of gods for advice on taking a marriage partner and they disallow such a union.[5]

William Caxton's account later in the 14th century is nearer the Phaedrus version. It is prefaced by the remark that 'of an evil man may well issue a worse than himself' and then relates the circumstances in which Aesop tells the tale. It is ‘all the nations of the world’ who appeal to Jupiter against the proposed marriage, realising for themselves the calamity that would follow from having more than one sun.[6] The story went on to be included by Jean de la Fontaine in his first collection of fables (1668), where it is told as a cautionary tale at a tyrant's wedding.[7]

Contemporary politics, however, were soon to give the fable an alternative reading, supporting the sovereign powers against the upstart, commercially successful Dutch Republic. The first to do so was the royalist John Ogilby, adding the fable to his 1665 edition, coupled with an illustration by Wenceslas Hollar of frogs demonstrating against the background of the Amsterdam Town Hall. According to this interpretation, the Republic was ungratefully throwing over its former ally who (in its own view, at least) had helped the Dutch to prosperity. The poem was also issued as a propaganda pamphlet under the title of The Frog, or the Low Countrey Nightingale during the Second Anglo-Dutch War.

A similar claim was made, using the same fable, during the Franco-Dutch War of 1672-8 in a European pamphlet war encompassing publications in Latin, French, Spanish and Italian.[8] La Fontaine's contribution was a long fable with the same title (Le soleil et les grenouilles), dating from this time but not included among his fables until the final volume. The (Dutch) frogs, having spread to every shore, are now complaining of the tyranny of the Solar Monarch (Louis XIV). The poem ends with a threat of the vengeance that the Sun will soon bring upon the impudence of ‘That kingless, half-aquatic crew’.[9]

Thereafter the subverted fable dropped from popularity until it was revived, in both France and Britain, during the 19th century. The La Fontaine version has also served as the basis for one of Ned Rorem’s micro-operas in 1971.[10]

References

- ↑ Aesopica site

- ↑ Robert William Browne, A history of Roman classical literature, London 1853 pp.345-6

- ↑ Fable 6

- ↑ Ebooks; original text in Les contes moralisés de Nicole Bozon, Paris 1889, p.115

- ↑ Minor Poems of John Lydgate

- ↑ Fable 1.7

- ↑ VI.12

- ↑ Paul J. Smith, "On cocks and frogs: fables and pamphlets around 1672", in Selling and Rejecting Politics in Early Modern Europe, Leuven B 2007, pp.105-12

- ↑ XII.24

- ↑ Boosey & Hawkes site