The Man who Runs after Fortune

“The man who runs after fortune" is the shortened title of La Fontaine's Fables, L'homme qui court après la fortune et l’homme qui l’attend dans son lit (The fortune-seeker and the layabout, VII.12).[1] It is one of the few that is of La Fontaine’s own invention but there are verbal echoes of other works. The title in the present tense points to the general lesson discussed in the prologue. The fable relates how an ambitious man suggests to his friend that they leave their small town together to seek their fortune. When his friend replies that he prefers to stay at home, the man departs to take up a position at Court. Not finding favour there, he next leaves to trade in the Orient but is no more successful. But when he gives up his pursuit and returns home at last, he find his friend in bed and Fortune sitting outside the door.

Emblems and echoes

Although there is no known source for the story as such, it has been suggested that La Fontaine had in mind the French proverb la fortune vient en dormant (fortune comes while one sleeps),[2] used of those who grow rich without exerting themselves.[3] A pictorial emblem was dedicated to this proposition in Guillaume Guéroult’s Le premier livre des emblemes (1550), a book that is considered the source of several more of La Fontaine’s fables.[4] Emblem 16 has the title Fortune favorise sans labour (Fortune favours those who labour not) and points out in an opening verse that the blind and inconstant goddess disdains those who work hard in her pursuit. The illustration features a naked huntsman and a sleeping monarch.[5]

La Fontaine prefaces his fable with a meditation on the difficulties and uncertainties of chasing fortune and what motivates people to do so. As a notable example of success he does not mention an earthly monarch but, “‘That man,’ say they, and feed their hope,/ ‘Raised cabbages — and now he’s pope'". Commentators cite several popes of humble origin, of whom the one that La Fontaine probably had in mind was the most recent, Sixtus V, once a swineherd in his youth.[6] Charles Denis, the first English translator of this fable, paraphrased the text radically and shifted La Fontaine’s preface to the end. There the Catholic reference is altered to something more in accord with his time: “Here is a fellow, you will say,/ Carried a knapsack t’other day, / In wretched, dismal, dirty plight,/ And now, forsooth, he’s dubb’d a Knight!”[7] La Fontaine himself, however, had then gone on to say in his preface that he prefers repose, which is the divine lot, an Epicurean doctrine according to the commentators.

Commentators also point out echoes of Latin writers within the text.[8] During his time at court, the fortune-seeker busies himself Se trouvant à tout, et n’arrivant à rien (being everywhere and getting nowhere), which may allude to the fable of “Tiberius Caesar and his Slave” by Phaedrus. The slave there is described as Multa agendo, nihil agens, “mightily employed and yet doing nothing”.[9] When the man decides to go trading, La Fontaine reflects on the bravery of those who sail the seas:

- O, human hearts are made of bronze!

- His must have been of adamant,

- Who ventured first this route to try.

In this case the allusion is to lines in an ode of Horace, Illi robur et aes triplex circa pectus erat, qui fragilem truci commisit pelago ratem primus (Odes.1.3), which translates as “Oak round his breast and triple brass, the sailor wore, whose bark first ventured on the sea.”[10]

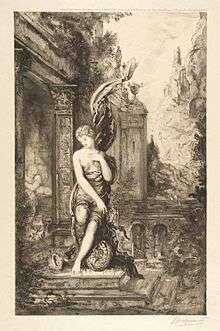

A slightly later emblem by Theodore Beza, in this case relating to the pursuit of glory, appears in his Vrais Pourtraits (1581). That pictures a man chasing his shadow while another is looking back at the shadow that the sun throws behind him. The accompanying verse points out that glory (which is but a shadow) flees the proud but accompanies the humble person who does not seek fame.[11] In this is summed up the substance of La Fontaine’s fable of those who, in his own words, “court a flighty phantom”. He was himself followed at a distance by Ivan Krylov in that fabulist’s more succinct but similar “The Man and his Shadow”, in the concluding commentary to which there are verbal echoes of La Fontaine’s preface.[12]

References

- ↑ Elizur Wright translation

- ↑ Andrew Calder, The Fables of La Fontaine: Wisdom Brought Down to Earth, Geneva CH, p.150

- ↑ French Wiktionary

- ↑ French Emblems at Glasgow

- ↑ Emblem 16

- ↑ Fables, Paris 1863, p.186

- ↑ Select Fables (1754) p.341

- ↑ Fables de Jean de La Fontaine, Paris 1829, p.49

- ↑ The Fables of Phaedrus in Latin and English, II. 5

- ↑ Horace, The Collected Works, London 1961, p.6; Lord Dunsany’s translation]

- ↑ Emblem 14

- ↑ W.R.S.Ralston, Krilof and his Fables, London 1889, pp.59-60