Treaty of Amity and Commerce (United States–France)

The Treaty of Amity and Commerce Between the United States and France, was the first of two treaties between the United States and France, signed on February 6, 1778 at the Hôtel de Crillon in Paris. Its sister treaty, the Treaty of Alliance, as well as a separate and secret clause related to the future inclusion of Spain[1] into the alliance were signed immediately thereafter. The Treaty of Amity and Commerce recognized the de facto independence of the United States and established a strictly commercial treaty between the two nations as an alternative to, and in direct defiance of, the British Acts of Trade and Navigation; the Treaty of Alliance, for mutual defense, was then signed "particularly in case Great Britain in Resentment of that connection and of the good correspondence which is the object of the [first] Treaty, should break the Peace with France, either by direct hostilities, or by hindering her commerce and navigation, in a manner contrary to the Rights of Nations, and the Peace subsisting between the two Crowns".[2] These were the first treaties ever negotiated by the fledgling United States and signed in the midst of the American Revolutionary War. Due to later complications with the alliance treaty, America would not sign another military alliance until the Declaration by United Nations in 1942.

Background

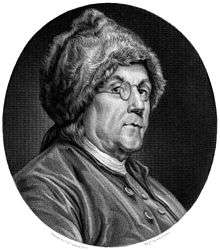

Early in 1776, as the members of the American Continental Congress began to move closer to declaring independence from Britain, leading American statesmen began to consider the benefits of forming foreign alliances to assist in their rebellion against the British Crown.[3] The most obvious potential ally was France, a long-time enemy of Britain and a colonial rival who had lost much of their lands in the Americas after the French and Indian War. As a result, John Adams began drafting conditions for a possible commercial treaty between France and the future independent colonies of the United States, which declined the presence of French troops and any aspect of French authority in colonial affairs.[3] On September 25 the Continental Congress ordered commissioners, led by Benjamin Franklin, to seek a treaty with France based upon Adams's draft treaty that had later been formalized into a Model Treaty which sought the establishment of reciprocal trade relations with France but declined to mention any possible military assistance from the French government.[4] Despite orders to seek no direct military assistance from France, the American commissioners were instructed to work to acquire most favored nation trading relations with France, along with additional military aid, and also encouraged to reassure any Spanish delegates that the United States had no desire to acquire Spanish lands in the Americas, in the hopes that Spain would in turn enter a Franco-American alliance.[3]

Despite an original openness to the alliance, after word of the Declaration of Independence and a British evacuation of Boston reached France, the French Foreign Minister, Comte de Vergennes, put off signing a formal alliance with the United States after receiving news of British victories over General George Washington in New York.[4] With the help of the Committee of Secret Correspondence, established by the Continental Congress to promote the American cause in France, and his standing as a model of republican simplicity within French society, Benjamin Franklin was able to gain a secret loan and clandestine military assistance from the Foreign Minister but was forced to put off negotiations on a formal alliance while the French government negotiated a possible alliance with Spain.[4]

With the defeat of Britain at the Battle of Saratoga and growing rumors of secret British peace offers to Franklin, France sought to seize an opportunity to take advantage of the rebellion and abandoned negotiations with Spain to begin discussions with the United States on a formal alliance.[4] With official approval to begin negotiations on a formal alliance given by King Louis XVI of France, the colonies turned down a British proposal for reconciliation in January 1778[5] and began negotiations that would result in the signing of the Treaty of Alliance and Treaty of Amity and Commerce.

Signers

United States

France

Provisions

- Peace and friendship between the U.S. and France

- Mutual most favored nation status with regard to commerce and navigation

- Mutual protection of all vessels and cargo when in U.S. or French jurisdiction

- Ban on fishing in waters possessed by the other with exception of the Banks of Newfoundland

- Mutual right for citizens of one country to hold land in other's territory

- Mutual right to search a ship of the other's coming out of an enemy port for contraband

- Right to due process of law if contraband is found on an allied ship and only after being officially declared contraband may it be seized

- Mutual protection of men-of-war and privateers and their crews from harm from the other party and reparations to be paid if this provision is broken

- Restoration of stolen property taken by pirates

- Right of ships of war and privateers to freely carry ships and goods taken for their enemy

- Mutual assistance, relief, and safe harbor to ships, both of War and Merchant, in crisis in the other's territory

- Neither side may commission privateers against the other nor allow foreign privateers that are enemies of either side to use their ports

- Mutual right to trade with enemy states of the other as long as those goods are not contraband

- If the two nations become enemies six months protection of merchant ships in enemy territory

- To prevent quarrels between allies all ships must carry passports and cargo manifests

- If two ships meet ships of war and privateers must stay out of cannon range but may board the merchant ship to inspect her passports and manifests

- Mutual right to inspection of a ship's cargo to only happen once

- Mutual right to have consuls, vice consuls, agents, and commissaries of one nation in the other's ports

- France grants one or more ports under its control to be free ports to ships of the United States

Ratification

The Treaty was received by Congress on May 2, 1778 and ratified on May 4, 1778 by unanimous vote, however, not all states were represented in the vote. It is certain that New Hampshire and North Carolina were not present for the vote. It is doubted whether Delaware was present and Massachusetts' presence is uncertain. Urgency overrode the necessity of having all thirteen states ratify the document.[6]

The Treaty was ratified by France on July 16, 1778.[7]

Articles 11 and 12

The day after ratification Congress expressed a desire that Articles 11 and 12 "be revoked and utterly expunged." These two articles dealt with a duty on and exportation of molasses. On September 1, 1778 they were formally suppressed and in France where the first printing of the treaty came in October, there was no reference to Articles 11 and 12. Thus, by omitting the original articles 11 and 12 all subsequent articles had to be renumbered and the original article 13 became article 11.[8]

See also

References

- ↑ Act Separate and Secret Between The United States and France; February 6, 1778

- ↑ Preamble of the Treaty of Alliance

- 1 2 3 Model Treaty (1776)

- 1 2 3 4 5 French Alliance, French Assistance, and European diplomacy during the American Revolution, 1778–1782

- ↑ Perspective on the French-American Alliance

- ↑ "Treaty of Amity and Commerce: 1778 – Hunter Miller's Notes," The Avalon Project at Yale Law School.

- ↑ Mary A. Giunta, ed., Documents of the Emerging Nation: U.S. Foreign Relations, 1775–1789 (Wilmington, Del.: Scholarly Resources, 1998), 59.

- ↑ "Hunter Miller's Notes."

Sources

- Giunta, Mary A., ed. Documents of the Emerging Nation: U.S. Foreign Relations 1775–1789. Wilmington, Del.: Scholarly Resources Inc., 1998.

- Middlekauff, Robert. The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763–1789. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982.

- "Treaty of Amity and Commerce," The Avalon Project at Yale Law School. http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/. Accessed March 30, 2008.

- "Treaty of Amity and Commerce: 1778 – Hunter Miller's Notes,"The Avalon Project at Yale Law School. http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/. Accessed March 30, 2008.

External links

- Avalon Project – Treaty of Amity and Commerce

- Avalon Project – Treaty of Amity and Commerce:1778 – Hunter Miller's Notes