Tropeognathus

| Tropeognathus Temporal range: Aptian-Albian, 112 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Restored skeleton of T. mesembrinus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | †Pterosauria |

| Suborder: | †Pterodactyloidea |

| Family: | †Ornithocheiridae |

| Genus: | †Tropeognathus Wellnhofer, 1987 |

| Type species | |

| †Tropeognathus mesembrinus Wellnhofer, 1987 | |

| Species | |

|

†T. mesembrinus Wellnhofer, 1987 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Tropeognathus is a genus of large pterosaurs from the late Cretaceous Period of South America. It was a member of the Ornithocheiridae (alternately Anhangueridae), a group of pterosaurs known for their keel-tipped snouts, and was closely related to species of the genus Anhanguera. The type and only species is Tropeognathus mesembrinus; a second species, Tropeognathus robustus, is now considered to belong to Anhanguera.

Discovery and naming

In the 1980s the German Bayerische Staatssammlung für Paläontologie und historische Geologie at Munich acquired a pterosaur skull from Brazilian fossil dealers that had probably been found in Ceará, in the Chapade do Araripe. In 1987 it was named and described as the type species Tropeognathus mesembrinus by Peter Wellnhofer. The generic name is derived from Greek τρόπις, tropis, "keel", and γνάθος, gnathos, "jaw". The specific name is derived from Koine mesembrinos, "of the noontide", "southern", in reference to the provenance from the Southern hemisphere.[1]

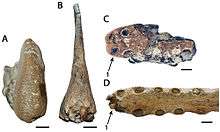

The holotype, BSP 1987 I 46, was discovered in a layer of the Romualdo Member of the Santana Formation, dating from the Aptian-Albian. It consists of a skull with lower jaws. A second specimen was referred by André Jacques Veldmeijer in 2002: SMNS 56994, consisting of partial lower jaws.[2] In 2013, Alexander Wilhelm Armin Kellner referred a third, larger, specimen: MN 6594-1, a skeleton with skull, with extensive elements of all body parts, except the tail and the lower hindlimbs.[3]

After Tropeognathus mesembrinus was named by Peter Wellnhofer in 1987[4] other researchers tended to consider it part of several other genera, leading to an enormous taxonomic confusion.[3] It was considered an Anhanguera mesembrinus by Alexander Kellner in 1989, a Coloborhynchus mesembrinus by Veldmeijer in 1998 and a Criorhynchus mesembrinus by Michael Fastnacht in 2001. In 2001, David Unwin referred the Tropeognathus material to Ornithocheirus simus, making Tropeognathus mesembrinus a junior synonym,[5] though he again reinstated a Ornithocheirus mesembrinus in 2003.[6] Veldmeijer in 2003 accepted that Tropeognathus and Ornithocheirus were cogeneric but rejecting O. simus as the type species of Ornithocheirus in favor of O. compressirostris (named Lonchodectes by Unwin), used the names Criorhynchus simus and Criorhynchus mesembrinus.[7] In 2000, Kellner again began to use the original name Tropeognathus mesembrinus. In 2013, Taissa Rodrigues and Kellner concluded Tropeognathus to be valid, and containing only T. mesembrinus.[3]

In 1987 Wellnhofer named a second species, Tropeognathus robustus, based on specimen BSP 1987 I 47, a more robust lower jaw.[1] Today, this is no longer considered cogeneric with Tropeognathus mesembrinus.[3]

Description

Tropeognathus mesembrinus is known to have reached wingspans of up to 8.2 m (27 ft), as can be inferred from the size of specimen MN 6594-1.[8] T. mesembrinus bore distinctive convex "keeled" crests on its snout and underside of the lower jaws.[9] The upper crests arose from the snout tip and extended back to the fenestra nasoantorbitalis, the large opening in the skull side. An additional, smaller crest projected down from the lower jaws at their symphysis ("chin" area).[10] While many ornithocheirids had a small, rounded bony crest projecting from the back of the skull, this was particularly large and well-developed in Tropeognathus.[7] The first five dorsal vertebrae are fused in to a notarium. Five sacral vertebrae are fused into a synsacrum. The third and fourth sacral vertebrae are keeled. The front blade of the ilium is strongly directed upwards.[8]

Classification

In 1987 Wellnhofer assigned Tropeognathus to a Tropeognathidae.[1] This concept was not adopted by other workers; Brazilian researchers place Tropeognathus mesembrinus in the Anhangueridae, their European colleagues tend to prefer the Ornithocheiridae.

Below is a cladogram showing the phylogenetic placement of this genus within Pteranodontia from Andres and Myers (2013).[11]

| Pteranodontia |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

In popular culture

Tropeognathus mesembrinus was the subject of an entire episode of the award-winning BBC television program Walking with Dinosaurs (which used the first name of its cousin Ornithocheirus but was incorrectly named as a species of it, as Ornithocheirus mesembrinus).[10] In Walking with Dinosaurs: A Natural History, a companion book to the series, it was claimed that several large bone fragments from the Santana Formation of Brazil indicated that O. mesembrinus may have had a wingspan reaching almost 12 m (39 ft) and a weight of 100 kg (220 lb), making it one of the largest known pterosaurs.[13] However, the largest definite Ornithocheirus mesembrinus specimens described at the time measured 6 m (20 ft) in wingspan.[4] The specimens which the producers of the program used to justify such a large size estimate were described in 2012, and were under study by Dave Martill and Heinz Peter Bredow at the time of Walking With Dinosaurs' production. The final description of the remains found a maximum estimated wingspan of 8.26 m (27 ft) for this large specimen.[8] Bredow stated that he did not believe the higher estimate used by the BBC was likely, and that the producers likely chose the highest possible estimate because it was more "spectacular."[14] Nevertheless, specimen MN 6594-V in 2013 was, at its degree of completeness, the largest known pterosaur individual.[8]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Peter Wellnhofer, 1987, "New crested pterosaurs from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil", Mitteilungen der Bayerischen Staatssammlung für Paläontologie und historische Geologie 27: 175–186; Muenchen

- ↑ Veldmeijer, A.J. 2002, "Pterosaurs from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil in the Stuttgart collection", Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde Serie B (Geologie und Paläontologie) 327: 1–27

- 1 2 3 4 Rodrigues, T.; Kellner, A. (2013). "Taxonomic review of the Ornithocheirus complex (Pterosauria) from the Cretaceous of England". ZooKeys. 308 (308): 1–112. doi:10.3897/zookeys.308.5559. PMC 3689139

. PMID 23794925.

. PMID 23794925. - 1 2 Wellnhofer, P. (1991). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Pterosaurs. New York: Barnes and Noble Books. pp. 124. ISBN 0-7607-0154-7.

- ↑ Unwin, D.M., 2001, "An overview of the pterosaur assemblage from the Cambridge Greensand (Cretaceous) of Eastern England", Mitteilungen aus dem Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin, Geowissenschaftliche Reihe 4: 189–221

- ↑ http://dml.cmnh.org/2003Sep/msg00388.html

- 1 2 Veldmeijer, A.J. (2006). "Toothed pterosaurs from the Santana Formation (Cretaceous; Aptian-Albian) of northeastern Brazil. A reappraisal on the basis of newly described material." Tekst. - Proefschrift Universiteit Utrecht.

- 1 2 3 4 Kellner, A. W. A.; Campos, D. A.; Sayão, J. M.; Saraiva, A. N. A. F.; Rodrigues, T.; Oliveira, G.; Cruz, L. A.; Costa, F. R.; Silva, H. P.; Ferreira, J. S. (2013). "The largest flying reptile from Gondwana: A new specimen of Tropeognathus cf. T. Mesembrinus Wellnhofer, 1987 (Pterodactyloidea, Anhangueridae) and other large pterosaurs from the Romualdo Formation, Lower Cretaceous, Brazil". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 85: 113. doi:10.1590/S0001-37652013000100009.

- ↑ Fastnacht, M. (2001). "First record of Coloborhynchus (Pterosauria) from the Santana Formation (Lower Cretaceous) of the Chapada do Araripe of Brazil." Paläontologisches Zeitschrift, 75: 23–36.

- 1 2 Unwin, David M. (2006). The Pterosaurs: From Deep Time. New York: Pi Press. p. 246. ISBN 0-13-146308-X.

- ↑ Andres, B.; Myers, T. S. (2013). "Lone Star Pterosaurs". Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 103 (3–4): 1. doi:10.1017/S1755691013000303.

- ↑ http://www.oum.ox.ac.uk/learning/pdfs/dinosaur.pdf

- ↑ Haines, T., 1999, "Walking with Dinosaurs": A Natural History, BBC Books, p. 158

- ↑ Bredow, H.P. (2000). "Re: WWD non-dino questions." Message to the Dinosaur Mailing List, 18 Apr 2000. Accessed online 20 Jan 2011: http://dml.cmnh.org/2000Apr/msg00446.html