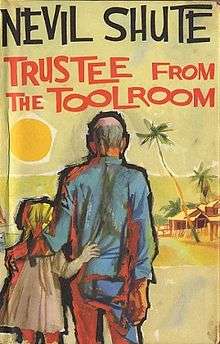

Trustee from the Toolroom

First edition | |

| Author | Nevil Shute |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Heinemann |

Publication date | 1960 |

Trustee from the Toolroom is a novel written by Nevil Shute. Shute died in January 1960; Trustee was published posthumously later that year.

Plot summary

The plot of the novel hinges on the actions of a modest technical journalist, Keith Stewart, whose life has been focused on the design and engineering of scale-model machinery. Stewart writes serial articles about how to create scale models in a magazine called the Miniature Mechanic, which are extremely well regarded in the modelling community — as is he.

Keith's sister had married a wealthy naval officer, recently retired from service at the opening of the story. The couple plan a long pleasure cruise in their small yacht before settling in British Columbia, meanwhile leaving their 10-year-old daughter with Keith and his wife. Before leaving, they ask Keith for assistance in hiding a jewelry box in the yacht's concrete ballast. When the couple are killed in a shipwreck in French Polynesia, Keith becomes the permanent guardian and trustee of his niece (hence the title). But, the solicitor handling the estate finds that the money has disappeared; the evidence suggests that Keith's brother-in-law converted his wealth into diamonds to take with him abroad in order to evade export and currency restrictions intended to prevent capital leaving Britain.

Keith infers that the metal box he secreted contained the diamonds, and he starts to investigate how he may retrieve them from the wreck. It is a difficult problem. Keith, while not poor, has chosen to do work he loves in place of better-paying work, and cannot afford to travel to Polynesia. He is able to call on connections in the model engineering world to deadhead his way on a flight as far as Hawaii. Finding no conventional way to get further which is within his means, he takes passage on the hand-built sailing ship of an illiterate half-Polynesian from Oregon, Jack Donelly.

One of the aircrew who took Keith to Hawaii worriedly approaches Keith's editor on his return to England. The editor, somewhat shocked at the risks that Keith is taking, starts trawling the close-knit world of miniature mechanics for someone who could help Keith. Eventually, Mr. Solomon Hirzhorn, who runs a vast timber business near Tacoma, Washington, is informed. Hirzhorn, an inexperienced modeller, has sent lengthy letters asking for elementary clarifications of Keith's modelling articles, which Keith always patiently answered. Hirzhorn is currently building one of Keith's designs, a Congreve clock, and jumps at the chance to help him. Hirzhorn arranges for the yacht of a business associate, Chuck Ferris, to proceed to Tahiti to help Keith out. Coincidentally, Keith and Jack had already consulted the yacht's captain for navigation advice in Honolulu.

Keith and Jack arrive safely in Tahiti but are in danger of being thrown into jail due to not having proper ship's papers. The yacht captain smooths over the situation, and brings Keith to the island where the wreck is located. There he meditates on the fate that has brought him so far, takes many pictures, erects a headstone, and salvages the yacht's engine, which he arranges to ship back to Britain to sell.

After an amusing incident where Ferris's much-married daughter, Dawn, runs off with Jack Donelly, the yacht proceeds to Washington State. Keith spends several days visiting Hirzhorn, helping him with his model. After Keith catches an engineering error in the contract between Hirzhorn's company and Ferris's that might have cost a couple of million dollars, Hirzhorn arranges for a large consultancy fee to be paid by Ferris's company and has his own company pay Stewart's airfare home.

The consultancy fee enables Keith's wife to stop working and take care of their niece. The diamonds are "discovered" by Keith in the oil in the engine's sump soon after it arrives, and proceeds from their sale enable them to take care of their niece's education and other needs. The other characters proceed on their lives happily, we are told at the end of what is probably Shute's most villain-free novel.

Major themes

The book is well loved by tool lovers, especially engineers and model engineers, for its reverent treatment of machinery, tools, and craftsmanship. The fictional magazine Miniature Mechanic is based on the actual British magazine, Model Engineer, and Shute himself admitted that the novel's protagonist is inspired by an author of that magazine, Edgar T. Westbury.[1] The novel's plot is not especially complex, nor is the novel's mystery terribly well hidden: the tension and drama of the story are generated by suspecting the outcome but not knowing how it will be achieved.

The novel represents a more liberal view of sexual conduct than we see in Shute's earlier books. The affair between Donelly and Dawn Ferris is accepted with amusement or resignation by most of the characters. In earlier books, such as A Town Like Alice, premarital sex was deprecated.

Several of the novel's characters come from groups subject to prejudice. The Hirzhorn family is Jewish, as is the diamond merchant Elias Franck. Jack Donelly is a 'coloured' American who is also illiterate and mentally 'deficient', although a talented boat-builder and sailor. The hero, Keith Stewart, is a 'working class' mechanic, although an extremely talented one. All four characters are portrayed in a positive light.

Footnotes

Trustee from the Toolroom was voted #27 on the Modern Library Readers' list of the top 100 novels.[2] The top ten in that poll, though, included four works by Ayn Rand and three by L. Ron Hubbard—according to David Ebershoff, Modern Library's publishing director, "the voting population [was] skewed."[3]

Bibliography

- Shute, Nevil (1960). "Trustee from the Toolroom". London: Heinemann. LCCN 60002940.. (U.S. co-edition: New York, Morrow, 1960, LCCN 60-9545.)

See also

References

- ↑ Model Engineer magazine, vol. 123 No 3102, 22. Dec. 1960

- ↑ "100 Best Novels". Modern Library. Retrieved 27 June 2011.

- ↑ http://www.caj.ca/mediamag/fall2002/opinion.html Archived April 4, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.