Typhoon Nabi

| Typhoon (JMA scale) | |

|---|---|

| Category 5 (Saffir–Simpson scale) | |

Typhoon Nabi on September 2, 2005 | |

| Formed | August 29, 2005 |

| Dissipated | September 10, 2005 |

| (Extratropical after September 8, 2005) | |

| Highest winds |

10-minute sustained: 175 km/h (110 mph) 1-minute sustained: 260 km/h (160 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 925 hPa (mbar); 27.32 inHg |

| Fatalities | 35 total |

| Damage | $972 million (2005 USD) |

| Areas affected | Northern Marianas Islands, Guam, Japan, South Korea, Russian Far East |

| Part of the 2005 Pacific typhoon season | |

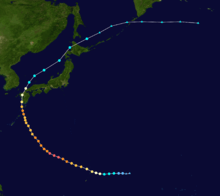

Typhoon Nabi, known in the Philippines as Typhoon Jolina, was a powerful typhoon that struck southwestern Japan in September 2005. The 14th named storm of the 2005 Pacific typhoon season, Nabi formed on August 29 to the east of the Northern Mariana Islands. It moved westward and passed about 55 km (35 mi) north of Saipan on August 31 as an intensifying typhoon. On the next day, the Joint Typhoon Warning Center upgraded the storm to super typhoon status, with winds equivalent to that of a Category 5 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale. The Japan Meteorological Agency estimated peak ten-minute winds of 175 km/h (110 mph) on September 2. Nabi weakened while curving to the north, striking the Japanese island of Kyushu on September 6. After brushing South Korea, the storm turned to the northeast, passing over Hokkaido before becoming extratropical on September 8.

The typhoon first affected the Northern Marianas Islands, where it left US$2.5 million in damage,[nb 1] while damaging or destroying 114 homes. The damage was enough to warrant a disaster declaration from the United States government. While passing near Okinawa, Nabi produced gusty winds and caused minor damage. Later, the western fringe of the storm caused several traffic accidents in Busan, South Korea, and throughout the country Nabi killed six people and caused US$115.4 million in damage. About 250,000 people evacuated along the Japanese island of Kyushu ahead of the storm, and there were disruptions to train, ferry, and airline services. In Kyushu, the storm left ¥4.08 billion[nb 2] (US$36.9 million) in crop damage after dropping 1,322 mm (52.0 in) of rain over three days. During the storm's passage, there were 61 daily rainfall records broken by Nabi's precipitation. The rains caused flooding and landslides, forcing people to evacuate their homes and for businesses to close. Across Japan, Nabi killed 29 people and caused ¥94.9 billion (US$854 million) in damage. Soldiers, local governments, and insurance companies helped residents recover from the storm damage. After affecting Japan, the typhoon affected the Kuril Islands of Russia, where it dropped the equivalent of the monthly precipitation, while also causing road damage due to high waves. Overall, Nabi killed 35 people, and its effects were significant enough for the name to be retired.

Meteorological history

On August 28, a large area of convection persisted about 1,035 km (645 mi) east of Guam. Located within an area of moderate wind shear, the system quickly organized while moving westward, its track influenced by a ridge to the north.[2] At 00:00 UTC on August 29, a tropical depression formed from the system,[3] classified by the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC)[nb 3] as Tropical Depression 14W. In initial forecasts, the agency anticipated steady strengthening,[5] due to warm sea surface temperatures in the area.[6] At 12:00 UTC on August 29, the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA)[nb 4] upgraded it to a tropical storm.[7] As such, the JMA named the storm Nabi.[nb 5][2] About 12 hours later, the JMA upgraded Nabi further to a severe tropical storm,[3] after the convection organized into spiral rainbands.[6] At 18:00 UTC, Nabi intensified to typhoon status, reaching ten-minute sustained winds of 120 km/h (75 mph).[3]

On August 31, Nabi passed about 55 km (35 mi) north-northeast of Saipan in the Northern Mariana Islands during its closest approach.[8] The typhoon continued to intensify quickly as it moved to the west-northwest. On September 1, the JTWC upgraded the storm to a super typhoon and later estimated peak one-minute winds of 260 km/h (160 mph); this is the equivalent of a Category 5 on the Saffir-Simpson scale. By contrast, the JMA estimated peak ten-minute winds of 175 km/h (110 mph) on September 2, with a barometric pressure of 925 mbar (27.3 inHg).[2][3] While at peak intensity, the typhoon developed a large 95 km (60 mi) wide eye.[9] For about 36 hours, Nabi maintained its peak winds, during which it crossed into the area of responsibility of PAGASA;[2][3] the Philippine-based agency gave it the local name "Jolina", although the storm remained away from the country.[2]

On September 3, Nabi began weakening as it turned more to the north, the result of an approaching trough weakening the ridge.[2] Later that day, the winds leveled off at 160 km/h (100 mph), according to the JMA. On September 5, Nabi passed near Minamidaitōjima and Yakushima, part of the Daitō and Ōsumi island groups offshore southern Japan.[7] Around that time, the JTWC estimated that the typhoon reintensified slightly to a secondary peak of 215 km/h (130 mph).[3] After turning due north, Nabi made landfall near Isahaya, Nagasaki around 05:00 UTC on September 6, after passing through the Izumi District of Kagoshima.[10] Shortly thereafter, the storm entered the Sea of Japan.[7] The typhoon turned to the northeast into the mid-latitude flow, influenced by a low over the Kamchatka Peninsula.[11] At 18:00 UTC on September 6, the JTWC discontinued advisories on Nabi, declaring it extratropical,[12] although the JMA continued tracking the storm. On the next day, Nabi moved across northern Hokkaido into the Sea of Okhotsk. The JMA declared the storm as extratropical on September 8, which continued eastward until dissipating on September 10 south of the Aleutian Islands.[7] The remnants of Nabi weakened and later moved into southwestern Alaska on September 12.[13]

Preparations

After Nabi formed as a tropical depression on August 29, the local National Weather Service office on Guam issued a tropical storm watch for the islands Tinian, Rota, Sapian, and Agrihan.[14] On August 30, the watch was upgraded to a tropical storm warning for Rota and Agrihan, while a typhoon warning was issued for Tinian and Saipan.[15] On all four islands, a Condition of Readiness 1 was declared. The government of the Northern Mariana Islands advised Tinian and Saipan residents along the coast and in poorly-built buildings to evacuate, and several schools operated as shelters.[16] About 700 people evacuated on Saipan,[17] and the airport was closed, stranding about 1,000 travelers.[18] As a precaution, schools were closed on Guam on August 31, after a tropical storm warning was issued for the island the night prior. The island's governor, Felix Perez Camacho, also declared a condition of readiness 2,[16] as well as a state of emergency.[19] Due to the typhoon, several flights were canceled or delayed at Antonio B. Won Pat International Airport on Guam.[20]

Ahead of the storm, United States Forces Japan evacuated planes from Okinawa to either Guam or mainland Japan to prevent damage.[21] Officials at the military bases on Okinawa advised residents to remain inside during the storm's passage. While Nabi was turning to the north, the island was placed under a Condition of Readiness 2.[22] At the military base in Sasebo, ships also evacuated,[23] and several buildings were closed after a Condition of Readiness 1 was declared.[24]

In Kyushu, officials evacuated over a quarter of a million people in fear of Typhoon Nabi affecting Japan.[25] These continued after the storm made landfall to protect residents from flood waters and landslides. The first order during the storm took place in the Arita district. In Miyazaki City, 21,483 households were evacuated following reports of significant overflow on the nearby river. Another 10,000 residences were vacated in Nobeoka following similar reports.[26] The entirety of the West Japan Railway Company was shut down.[2] Canceled train services affected 77,800 people on Shikoku.[27] Ferry service was also shut down, cutting off transportation for tens of thousands of people. In addition, at least 723 flights were cancelled because of the storm.[28] Japan's second-largest refinery, Idemitsu Kosan, stopped shipments to other refineries across the area, and Japan's largest refinery, Nippon Oil, stopped all sea shipments. The Cosmo Oil Company, Japan's fourth largest refinery, stopped all shipments to Yokkaichi and Sakaide refineries.[29] About 700 schools in the country were closed. Approximately 1,500 soldiers were dispatched to Tokyo to help coastal areas prepare for Typhoon Nabi's arrival, and to clean up after the storm.[30] Officials in the Miyazaki Prefecture issued a flood warning for expected heavy rains in the area.[26]

In South Korea, the government issued a typhoon warning for the southern portion of the country along the coast, prompting the airport at Pohang to close,[31] and forcing 162 flights to be canceled.[32] Ferry service was also disrupted,[32] and thousands of boats returned to port.[33] The storm also prompted 138 schools to close in the region.[32] Earlier, the storm spurred fears of a possible repeat of either typhoon Rusa in 2002 or Maemi in 2003, both of which were devastating storms in South Korea.[34] Officials in the Russian Far East issued a storm warning for Vladivostok, advising boats to remain at port.[35]

Impact

While passing between Saipan and the volcanic island of Anatahan, Nabi brought tropical storm force winds to several islands in the Northern Mariana Islands. Saipan International Airport reported sustained winds of 95 km/h (59 mph), with gusts to 120 km/h (75 mph). Also on the island, Nabi produced 173 mm (6.82 in) of rainfall. The storm destroyed two houses and left 26 others uninhabitable, while 77 homes sustained minor damage, largely from flooding or roof damage. Nabi damaged 70–80% of the crops on Saipan and also knocked down many trees, leaving behind 544 tonnes (600 tons) of debris. The entire island was left without power, some without water, after the storm. On Tinian to the south, Nabi damaged or destroyed nine homes, with heavy crop damage. On Rota, there was minor flooding and scattered power outages. Farther south, the outer reaches of the storm produced sustained winds of 69 km/h (43 mph) at Apra Harbor on Guam, while gusts peaked at 101 km/h (63 mph) at Mangilao.[17] Gusts reached 72 km/h (45 mph) at the international airport on Guam, the highest during 2005. The storm dropped 115 mm (4.53 in) of rainfall in 24 hours on the island.[36] Flooding covered roads for several hours and entered classrooms at Untalan Middle School, forcing hundreds of students to evacuate. Damage in the region was estimated US$2.5 million.[17] After Nabi exited the region, it produced high surf for several days on Guam and Saipan.[36]

Later in its duration, Nabi brushed southeastern South Korea with rainbands.[2] Ulsan recorded a 24‑hour rainfall total of 319 mm (12.6 in),[2] while Pohang recorded a record 24‑hour total of 540.5 mm (21.28 in).[37] The highest total was 622.5 mm (24.5 in) of rainfall.[38] The periphery of the storm produced gusts of 121 km/h (75 mph) in the port city of Busan,[33] strong enough to damage eight billboards and knock trees over.[2] Heavy rains caused several traffic accidents and injuries in Busan,[33] while strong waves washed a cargo ship ashore in Pohang.[2] Throughout South Korea, the storm led to six fatalities and caused US$115.4 million in damages.[38]

In the Kuril Islands of Russia, Nabi dropped about 75 mm (3 in) of rain, equivalent to the monthly average. Gusts reached 83 km/h (51 mph), weak enough not to cause major damage. During the storm's passage, high waves washed away unpaved roads in Severo-Kurilsk.[39]

Japan

The outer rainbands of Nabi began affecting Okinawa on September 3.[40] The storm's strongest winds ended up bypassing the island, and wind gusts peaked at 85 km/h (53 mph).[23] Two elderly women were injured from the wind gusts. There were minor power outages and some houses were damaged.[41] In the Amami Islands between Okinawa and mainland Japan, Nabi produced gusts of 122 km/h (76 mph) in Kikaijima.[42] Waves of 9 m (30 ft) in height affected Amami Ōshima.[43]

While moving through western Japan, Nabi dropped heavy rainfall that totaled 1,322 mm (52.0 in) over a three-day period in Miyazaki Prefecture,[42][44] the equivalent to nearly three times the average annual precipitation.[45] The same station in Miyazaki reported a 24‑hour rainfall total of 932 mm (36.7 in), as well as an hourly total of 66 mm (2.6 in).[42] Within the main islands of Japan, Nabi dropped 228.6 mm (9 in) of rainfall per hour in the capital Tokyo.[2]

During the storm's passage, there were 61 daily rainfall records broken by Nabi's precipitation across Japan.[2] The rains from Nabi caused significant slope failures and large accumulations of driftwood. The amount of sediment displaced by the rains was estimated at 4,456 m3/km2, over four times the yearly average. A total of 630 m3 (2,066 ft3) of driftwood was recorded.[46] However, the rainfall also helped to end water restrictions in Kagawa and Tokushima prefectures.[47][48] In addition to the heavy rainfall, Nabi produced gusty winds on the Japan mainland, peaking at 115 km/h (72 mph) in Muroto. A station on Tobishima in the Sea of Japan recorded a gust of 119 km/h (74 mph).[42] The typhoon spawned a F1 tornado in Miyazaki, which damaged several buildings.[49] In Wajima, Ishikawa, Nabi produced a Foehn wind, causing temperatures to rise quickly.[50]

| Precipitation | Storm | Location | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | mm | in | |||

| 1 | 2781.0 | 109.50 | Fran 1976 | Hiso | [51] |

| 2 | >2000.0 | >78.74 | Namtheum 2004 | Kisawa | [52] |

| 3 | 1805.5 | 71.08 | Talas 2011 | Kamikitayama | [53] |

| 4 | 1518.9 | 59.80 | Olive 1971 | Ebino | [54] |

| 5 | 1322.0 | 52.04 | Nabi 2005 | Mikado | [55] |

| 6 | 1286.0 | 50.62 | Kent 1992 | Hidegadake | [56] |

| 7 | 1167.0 | 45.94 | Judy 1989 | Hidegadake | [57] |

| 8 | 1138.0 | 44.80 | Abby 1983 | Amagisan | [58] |

| 9 | 1124.0 | 44.25 | Flo 1990 | Yanase | [59] |

| 10 | ~1092.0 | ~43.00 | Trix 1971 | Yangitake | [60] |

Throughout Japan, Nabi caused damage in 31 of the 47 prefectures,[61] leaving over 270,000 residences without power.[2] Torrential rains caused flooding and landslides throughout the country.[62] The storm destroyed 7,452 houses and flooded 21,160 others.[42] Several car assembly plants were damaged in southwestern Japan,[2] while others were closed due to power outages, such as Toyota, Mazda, and Mitsubishi.[63] In addition, the storm wrecked about 81 ships along the coast.[42] On the island of Kyushu, damage in Ōita Prefecture on Kyushu reached ¥11.7 billion (US$106 million), the fifth highest of any typhoon in the preceding 10 years; about 20% of the total there was related to road damages.[64] In nearby Saga Prefecture, crop damage totaled about ¥1.06 billion (US$9.6 million), mostly to rice but also to soybeans and various other vegetables.[65] Crop damage as a whole on Kyushu totaled ¥4.08 billion (US$36.9 million).[45]

In the capital city of Tokyo, heavy rainfall increased levels along several rivers, which inundated several houses.[66] Strong winds damaged ¥28.8 million (US$259,000) in crop damage in Gifu Prefecture,[67] and ¥27.1 million (US$244,000) in crop damage in Osaka.[68] In Yamaguchi Prefecture on western Honshu, Nabi damaged a portion of the historical Kintai Bridge, originally built in 1674.[69] In Yamagata Prefecture, the winds damaged a window in a school, injuring several boys from the debris.[70] One person was seriously injured in Kitakata, Fukushima after strong winds blew a worker from scaffolding of a building under construction.[71] Effects from Nabi spread as far north as Hokkaido, where heavy rainfall damaged roads and caused hundreds of schools to close.[72] In Ashoro, an overflown river flooded a hotel,[73] and a minor power outage occurred in Teshikaga.[74]

Ahead of the storm, high waves and gusty winds led to one drowning when a woman was knocked off a ferry in Takamatsu, Kagawa. A landslide in Miyazaki destroyed five homes,[75] killing three people. A man who was listed as missing was found dead in a flooded rice field. In Tarumi, a landslide buried a home in mud, killing two people.[62] Nabi caused a portion of the San'yō Expressway to collapse in Yamaguchi Prefecture, killing three people.[66] In Fukui Prefecture, the winds knocked an elderly man off a bicycle, killing him.[76] Overall, Nabi killed 29 people in Japan and injured 179 others, 45 of them severely. Damage was estimated at ¥94.9 billion (US$854 million).[42]

Aftermath

After the storm, members of Marine Corps Air Station Iwakuni provided $2,500 to the town of Iwakuni toward cleanup and disaster relief.[77] Soldiers also helped nearby residents and farmers to complete the rice harvest, after floods from the typhoon damaged harvesting machines.[78] The local government of Iwakunda distributed disinfectant chemicals to flooded houses.[79] Closed markets and decreased supplies caused the price of beef to reach record levels in the country.[80] Following the storm, the General Insurance Association of Japan reported that insurance claims from the typhoon totaled ¥58.8 billion (US$53 million), the tenth-highest for any natural disaster in the country. Miyazaki Prefecture reported the highest claims with ¥12.6 billion (US$11.4 million). The total was split between ¥49 billion (US$44 million) in housing claims and ¥7.9 billion (US$71 million) in car claims.[81] The Japanese government provided food, water, and rescue workers to the affected areas in the days after the storm, along with Japan Post, the local post system; trucks were mobilized to affected towns, accompanied by a mobile bank and insurance agent.[82]

On November 8, nearly two months after the dissipation of Typhoon Nabi, President George W. Bush declared a major disaster declaration for the Northern Mariana islands. The declaration allocated aid from the United States to help restore damaged buildings, pay for debris removal, and other emergency services. Federal funding was also made available on a cost-sharing basis for the islands to mitigate against future disasters.[83] The government ultimately provided $1,046,074.03 to the commonwealth.[84]

Due to the damage of the storm in Japan, the Typhoon Committee of the World Meteorological Organization agreed to retire the name Nabi. The agency replaced it with the name Doksuri, effective January 1, 2007.[85]

See also

- Typhoon Mireille - costliest typhoon in Japan history that struck southwestern Japan in 1991

- Typhoon Songda - similarly destructive typhoon that took a similar path to Nabi in 2004

Notes

- ↑ All damage totals are in 2003 values of their respective currencies.

- ↑ All Japanese monetary figures were originally in Japanese yen. Totals were converted via the Oanda Corporation website.[1]

- ↑ The Joint Typhoon Warning Center is a joint United States Navy – United States Air Force task force that issues tropical cyclone warnings for the western Pacific Ocean and other regions.[4]

- ↑ The Japan Meteorological Agency is the official Regional Specialized Meteorological Center for the western Pacific Ocean.[7]

- ↑ The name Nabi was submitted to the World Meteorological Organization by South Korea, meaning butterfly.[2]

References

- ↑ "Historical Exchange Rates". Oanda Corporation. 2013. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Kevin Boyle; Huang Chunliang. "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Summary August 2005". Gary Padgett. Retrieved May 27, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 2005 Nabi (2005241N15155). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Retrieved May 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Joint Typhoon Warning Center Mission Statement". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 2011. Archived from the original on July 26, 2007. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- ↑ Joint Typhoon Warning Center (August 28, 2005). Tropical Depression 14W Warning NR 001 (Report). Unisys Corporation. Retrieved May 27, 2014.

- 1 2 Japan Meteorological Agency (August 29, 2005). Reasoning No. 3 for STS 0514 (Nabi) (0514) (Report). Unisys Corporation. Retrieved May 27, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Annual Report on Activities of the RSMC Tokyo: Typhoon Center 2005 (PDF) (Report). Japan Meteorological Agency. 8. Retrieved May 27, 2014.

- ↑ Mike Ziobro (August 31, 2005). Typhoon Nabi (14W) Position Estimate. Tinian, Guam National Weather Service (Report). Unisys Corporation. Retrieved May 27, 2014.

- ↑ Joint Typhoon Warning Center (September 1, 2005). Super Typhoon 14W (Nabi) Warning NR 015 (Report). Unisys Corporation. Retrieved May 27, 2014.

- ↑ 台風0514号(0514 NABI) (PDF) (Report) (in Japanese). Japan Meteorological Agency. Retrieved March 21, 2016.

- ↑ Patrick A. Harr; Doris Anwender; Sarah C. Jones (September 2008). "Predictability Associated with the Downstream Impacts of the Extratropical Transition of Tropical Cyclones: Methodology and a Case Study of Typhoon Nabi (2005)". Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 136. Bibcode:2008MWRv..136.3205H. doi:10.1175/2008MWR2248.1. Retrieved May 27, 2014.

- ↑ Joint Typhoon Warning Center (September 6, 2005). Tropical Storm 14W (Nabi) Warning NR 035 (Report). Unisys Corporation. Retrieved May 27, 2014.

- ↑ George P. Bancroft (April 2006). "Marine Weather Review—North Pacific Area September through December 2005". Mariners Weather Log. 50 (1). Retrieved May 27, 2014.

- ↑ Carl McElroy (August 28, 2005). Tropical Depression 14W Advisory Number 1. Tinian, Guam National Weather Service (Report). Unisys Corporation. Retrieved May 27, 2014.

- ↑ Mike Ziobro (August 29, 2005). Tropical Storm Nabi (14W) Advisory Number 4. Tinian, Guam National Weather Service (Report). Unisys Corporation. Retrieved May 27, 2014.

- 1 2 Tropical Storm Nabi (14W) Local Statement. Tinian, Guam National Weather Service (Report). Unisys Corporation. August 30, 2005. Retrieved May 27, 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena". Storm Data. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 47 (8): 223. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 28, 2014. Retrieved May 28, 2014.

- ↑ "Northern Marianas Clean Up After Typhoon Nabi". Terra Daily. Agence France-Presse. September 1, 2005. Retrieved May 28, 2014.

- ↑ Felix Perez Camacho (August 31, 2005). "Relative to Declaring an Emergency in Order to Expedite the Island-Wide Preparation and Recovery from Typhoon Nabi (14W)" (PDF). Office of the Governor of Guam. Retrieved May 28, 2014.

- ↑ U.S. Department of Homeland Security (August 31, 2005). "Typhoon Nabi Affects Air Service". Guam Homeland Security. Archived from the original on March 31, 2006. Retrieved May 28, 2014.

- ↑ Dave Ornauer (September 3, 2005). "Typhoon Nabi Shifts Course, Now Heading to Okinawa". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- ↑ Dave Ornauer (September 4, 2005). "Okinawa Troops Bracing for Super Typhoon Nabi". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- 1 2 "Nabi Turns Its Force Toward Sasebo, Iwakuni". Stars and Stripes. September 5, 2005. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- ↑ Greg Tyler; David Allen (September 7, 2005). "Sasebo Braces for Arrival of Typhoon Nabi". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- ↑ Hector Forster (September 7, 2005). "Typhoon Nabi Hits Western Japan, Leaving Seven Dead (Update1)". Bloomberg News.

- 1 2 藤吉洋一郎, 有馬正敏, 水上知之, 天野 篤, 大妻女子大学教授 解説委員 日本災害情報学会副会長 (November 4, 2006). 台風 0514 号災害 宮崎・鹿児島現地調査(速報) (PDF) (in Japanese). デジタル放送研究会. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- ↑ Weather Disaster Report (2005-891-10) (Report). Digital Typhoon. Retrieved June 4, 2014.

- ↑ Hector Forster (September 7, 2005). "Typhoon Nabi Heads Back to Sea After Lashing Kyushu (Update3)". Bloomberg News.

- ↑ Hector Forster; Hiroshi Suzuki (September 5, 2005). "Typhoon Nabi Makes Landfall in Kyushu; 47,000 Homes Evacuated". Bloomberg News.

- ↑ "Typhoon Nabi Moves to Hokkaido Leaving More than 18 People Dead and 140 Wounded". Asia News. September 8, 2005. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- ↑ Kim Yoon-mi (September 6, 2005). "Typhoon Warning Issued as Nabi Approaches Southern Korea". The Korea Herald. – via LexisNexis (subscription required)

- 1 2 3 "Typhoon Nabi Causes Damage in S.Korean Coastal Areas". Xinhua. September 6, 2005. Retrieved June 5, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Jin Hyun-joo (September 7, 2005). "Nabi Hits the Peninsula, Causing Damages". The Korea Herald. – via LexisNexis (subscription required)

- ↑ Cho Chung-un (September 3, 2005). "Typhoon Nabi Likely to Hit Korea". The Korea Herald. – via LexisNexis (subscription required)

- ↑ "Typhoon Nabi Closes in on Russia's Far East". RIA Novosti. September 7, 2005. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- 1 2 Water and Environmental Research Institute of the Western Pacific (WERI) at the University of Guam. "Pacific ENSO Update 1st Quarter, 2006 Vol. 12 No. 1". University of Hawaii School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology. Retrieved May 28, 2014.

- ↑ Jin Hyun-joo (September 8, 2005). "3 Still Missing, 70 Left Homeless After Typhoon Nabi's Downpours". The Korea Herald. – via LexisNexis (subscription required)

- 1 2 "Natural Hazards in Republic of Korea in 2005" (PDF). National Institute for Disaster Prevention. 2006. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- ↑ "Typhoon Brings Heavy Rainfall to North Kurils". RIA Novosti. September 9, 2005. – via LexisNexis (subscription required)

- ↑ Dave Ornauer (September 4, 2005). "Officials: Nabi Won't Be as Bad as Katrina". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- ↑ Weather Disaster Report (2005-936-12) (Report). Digital Typhoon. Retrieved June 4, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Typhoon 200514 (Nabi) – Disaster Information (Report). Digital Typhoon. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- ↑ "Typhoon Nabi Lashes Japan". The Courier Mail. Queensland, Australia. Reuters. September 6, 2005. – via LexisNexis (subscription required)

- ↑ "WMO Statement on the Status of the Global Climate in 2005" (DOC). World Meteorological Organization. December 15, 2005. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- 1 2 "22 Killed, Nine Missing in Japan, S.Korea as Powerful Tropical Storm Heads Borth". AP Worldstream. September 9, 2005. – via LexisNexis (subscription required)

- ↑ "Slope Failures and Movement of Driftwoods Caused by Typhoon Nabi" (PDF). Department of Environmental Sciences and Technology, Faculty of Agriculture, Kagoshima University. November 18, 2006. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- ↑ Weather Disaster Report (2005-891-05) (Report). Digital Typhoon. Retrieved June 4, 2014.

- ↑ Weather Disaster Report (2005-895-04) (Report). Digital Typhoon. Retrieved June 4, 2014.

- ↑ Weather Disaster Report (2005-830-07) (Report). Digital Typhoon. Retrieved June 4, 2014.

- ↑ Weather Disaster Report (2005-605-08) (Report). Digital Typhoon. Retrieved June 4, 2014.

- ↑ Ikuo Tasaka (1981). "The Difference of Rainfall Distribution in Relation to Time-Scale: A Case Study on Heavy Rainfall of September 8–13, 1976, in the Shikoku Island Caused by Typhoon 7617 Fran" (PDF). Geographical Review of Japan (in Japanese). 54 (10): 570–578. doi:10.4157/grj.54.570. Retrieved January 5, 2016.

- ↑ Gonghui Wang; Akira Suemine; Gen Furuya; Masahiro Kaibori & Kyoji Sassa (2006). Rainstorm-induced landslides in Kisawa village, Tokushima Prefecture, Japan (PDF) (Report). International Association for Engineering Geology. Retrieved January 5, 2016.

- ↑ "Typhoon Talas". Japan Meteorological Agency. 2011. Retrieved September 6, 2011.

- ↑ "Climatological Data: National Summary". 22 (1). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. January 1971: 771. Retrieved April 12, 2013.

- ↑ (Japanese) "台風200514号 (Nabi) - 災害情報". National Institute of Informatics. 2011. Retrieved December 31, 2011.

- ↑ (Japanese) "台風199211号 (Kent) - 災害情報". National Institute of Informatics. 2011. Retrieved December 31, 2011.

- ↑ (Japanese) "アメダス日出岳(64211)@台風198911号". National Institute of Informatics. 2011. Retrieved December 31, 2011.

- ↑ (Japanese) "台風198305号 (Abby) - 災害情報". National Institute of Informatics. 2011. Retrieved December 31, 2011.

- ↑ (Japanese) "台風199019号 (Flo) - 災害情報". National Institute of Informatics. 2011. Retrieved December 31, 2011.

- ↑ "Annual Tropical Cyclone Report: Typhoon Trix" (PDF). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. United States Navy. 1972. pp. 183–192. Retrieved April 12, 2013.

- ↑ Charles Enman (December 18, 2005). "Year of Disasters". The Ottawa Citizen. – via LexisNexis (subscription required)

- 1 2 "Typhoon Nabi Leaves 32 Dead or Missing in Japan". People's Daily Online. September 8, 2005. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- ↑ "VOA News: Typhoon Disrupts Production in Southern Japan". US Fed News. September 9, 2005. – via LexisNexis (subscription required)

- ↑ "Typhoon Nabi Causes $106.1 Mln Damages to Japan Oita". Japanese Business Digest. September 13, 2005. – via LexisNexis (subscription required)

- ↑ "Typhoon Nabi Causes $9.56 Mln Damages to Japan Saga Agriculture". Japanese Business Digest. September 9, 2005. – via LexisNexis (subscription required)

- 1 2 Weather Disaster Report (2005-662-09) (Report). Digital Typhoon. Retrieved June 4, 2014.

- ↑ Weather Disaster Report (2005-632-12) (Report). Digital Typhoon. Retrieved June 4, 2014.

- ↑ Weather Disaster Report (2005-772-08) (Report). Digital Typhoon. Retrieved June 4, 2014.

- ↑ Mikio Koshihara. The Secular Change of the Timber Bridge "Kintai-Kyo" (PDF) (Report). World Conference on Timber Engineering. Retrieved June 17, 2014.

- ↑ Weather Disaster Report (2005-588-13) (Report). Digital Typhoon. Retrieved June 4, 2014.

- ↑ Weather Disaster Report (2005-595-09) (Report). Digital Typhoon. Retrieved June 4, 2014.

- ↑ Weather Disaster Report (2005-407-02) (Report). Digital Typhoon. Retrieved June 4, 2014.

- ↑ Weather Disaster Report (2005-417-03) (Report). Digital Typhoon. Retrieved June 4, 2014.

- ↑ Weather Disaster Report (2005-418-04) (Report). Digital Typhoon. Retrieved March 12, 2016.

- ↑ "Typhoon Nabi Pounds Japan". Ireland On-line. September 6, 2005. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- ↑ Weather Disaster Report (2005-616-10) (Report). Digital Typhoon. Retrieved June 4, 2014.

- ↑ Greg Tyler (November 26, 2005). "Iwakuni Gives $2,500 to Typhoon Nabi Victims". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- ↑ "Station Residents Connect with Japan's Past". US Fed News. October 2, 2005. – via LexisNexis (subscription required)

- ↑ "Iwakuni Distributes Undiluted Disinfectants in Beverage Bottles". Japan Economic Newswire. September 21, 2005. – via LexisNexis (subscription required)

- ↑ "Japanese beef price hits new record high due to import ban". Japan Economic Newswire. September 12, 2005. – via LexisNexis (subscription required)

- ↑ "Insurance Claims Related to Typhoon Nabi at 58.8 B. Yen". Jiji Press Ticker Service. September 15, 2005. – via LexisNexis (subscription required)

- ↑ Joseph Coleman (September 9, 2005). "Japan Post Privatization Debate in Spotlight Ahead of Weekend Elections". Associated Press. – via LexisNexis (subscription required)

- ↑ "President Declares Major Disaster for the Mariana Islands". Federal Emergency Management Agency. November 9, 2005. Retrieved May 28, 2014.

- ↑ "Financial Assistance to Help Families and Communities Recover". Federal Emergency Management Agency. Retrieved May 28, 2014.

- ↑ The Typhoon Committee. ESCAP/WMO Typhoon Committee Thirty-Ninth Session (PDF) (Report). World Meteorological Organization. p. 5. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Typhoon Nabi. |

- RSMC Tokyo - Typhoon Center

- Best Track Data of Typhoon Nabi (0514) (Japanese)

- Best Track Data (Graphics) of Typhoon Nabi (0514)

- Best Track Data (Text)

- JTWC Best Track Data of Super Typhoon 14W (Nabi)