Tzompantli

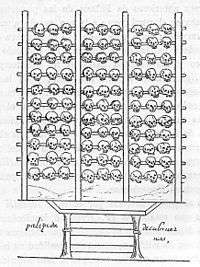

A tzompantli [t͡somˈpant͡ɬi] or skull rack is a type of wooden rack or palisade documented in several Mesoamerican civilizations, which was used for the public display of human skulls, typically those of war captives or other sacrificial victims. It is a scaffold-like construction of poles on which heads and skulls were placed after holes had been made in them.[1] Many have been documented throughout Mesoamerica, and range from the Epiclassic (ca. 600–900 CE) through early Post-Classic (ca. 900–1250 CE).[2]

Etymology

The name comes from the Classical Nahuatl language of the Aztecs, however it is also commonly applied to similar structures depicted in other civilizations. Its precise etymology is uncertain, although its general interpretation is "skull rack", "wall of skulls", or "skull banner".[3] It may be seen to be a compound of the Nahuatl words tzontecomatl ("skull"; from tzontli or tzom- "hair", "scalp" and tecomatl ("gourd" or "container"), and pamitl ("banner"). This derivation has been ascribed to explain the depictions in several codices which associate these with banners; however, Nahuatl linguist Frances Karttunen[4] has proposed that pantli means merely "row" or "wall".

Distribution

General information

It was most commonly erected as a linearly-arranged series of vertical posts connected by a series of horizontal crossbeams. The skulls were pierced or threaded laterally along these horizontal stakes. An alternate arrangement, more common in the Maya regions, was for the skulls to be impaled on top of one another along the vertical posts.[5]

Tzompantli are known chiefly from their depiction in Late Postclassic (13th to 16th centuries) and post-Conquest (mid-16th to 17th centuries) codices, contemporary accounts of the conquistadores, and several other inscriptions. However, a tzompantli-like structure, thought to be the first instance of such structures, has been excavated from the Proto-Classic Zapotec civilization at the La Coyotera, Oaxaca site, dated from c. 2nd century BCE to 3rd century CE.[6] The Zapotecs called this structure a "yàgabetoo," and it displayed 61 skulls.[7]

Tzompantli are also noted in other Mesoamerican pre-Columbian cultures, such as the Toltec and Mixtec.[8][9]

Toltec

At the Toltec capital of Tula exists the first indications in Central Mexico of a real fascination with skulls and skeletons. Tula flourished from the ninth century until the thirteenth century A.D. The site includes the decimated remains of a tzompantli. The tzompantli at Tula displayed multiple rows of stone carved skulls adorning the sides of a broad platform upon which the actual skulls of sacrificial victims were exhibited. The tzompantli appeared during the final phases of civilization at Tula, which was destroyed around 1200 A.D.[10]

Maya

Other examples are indicated from Maya civilization sites such as Uxmal and other Puuc region sites of the Yucatán, dating from around the late 9th-century decline of the Maya Classical Era. A particularly fine and intact inscription example survives at the extensive Chichen Itza site.[11]

Human sacrifice on a large scale was introduced to the Maya by the Toltecs from the appearances of the tzompantli by the Chichen Itza ball courts. Six ball court reliefs at Chichen Itza depict the decapitation of a ball player; it seems that the losers would be beheaded and would have their skulls placed on the Tzompantli.[12]

Aztec

The Aztecs had their share of tzompantli; one such example is in the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan. The skull rack here is a reminder of the Aztec's ongoing Flowery Wars.[13] Aztec warfare was primarily concerned with the capture of enemy warriors to serve as sacrifice, which is evident from the number of warriors found sacrificed around Aztec structures.[14] The heart of the captive would be torn from his chest, and the corpse pushed down the stairs at the front of the temple. Attendants at the bottom were responsible for severing the limbs and head from the torso, and the warrior who brought the captive in would be given the limbs as property. Many scholars have determined that these limbs would be cannibalized [15]

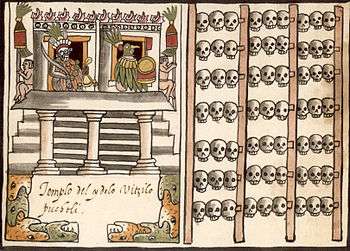

One conquistador, Andrés de Tapia, was given the task of counting the skulls on the "tzompantli" at Tenochtitlan estimated that there were 136,000 skulls on it.[16] However, based on numbers given by Taipa and Fray Diego Durán, Bernard Ortiz de Montellano[17] has calculated that there were at most 60,000 skulls on the "Hueyi Tzompantli" (Great Skullrack) of Tenochtitlan. The "Hueyi Tzompantli" consisted of a massive masonry platform composed of “thirty long steps” measuring fully 60 meters in length by 30 meters wide at its summit. Atop of the aforementioned platform was erected an equally formidable wooden palisade and scaffolding consisting of between 60 and 70 massive uprights or timbers woven together with an impressive constellation of horizontal cross beams upon which were suspended the tens of thousands of decapitated human heads once impaled thereon.[18] There were at least five more skull racks in Tenochtitlan but by all accounts they were much smaller.

According to Bernal Díaz del Castillo's eye-witness account (The Conquest of New Spain) written several decades after the event, after Cortes' expedition was forced to make their initial retreat from Tenochtitlan, the Aztecs erected a makeshift tzompantli to display the severed heads of men and horses they had captured from the invaders. This taunting is also depicted in an Aztec codex which relates the story, and the subsequent battles which led to the eventual capture of the city by the Spanish forces and their allies.[19]

There are numerous depictions of tzompantli in Aztec codices, dating from around the time or shortly after the Spanish conquest of Mexico, such as the Durán Codex, Ramírez Codex and Codex Borgia. During the stay of Cortes' expedition in the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan (initially as guest-captives of the Emperor Moctezuma II, before the battle which would lead to the conquest), they reported a wooden tzompantli altar adorned with the skulls from recent sacrifices.[20] Within the complex of the Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan (Templo Mayor) itself, a relief in stucco depicted these sacrifices; the remains of this relief have survived and may now be seen in the ruins in the Zócalo of present-day Mexico City.

Association and Meaning

Apart from their use to display the skulls of ritualistically-executed war captives, tzompantli often occur in the contexts of Mesoamerican ball courts, which were widespread throughout the region's civilizations and sites. The game was 'played for keeps' ending with the losing team being sacrificed. The captain of the winning team was tasked with taking the head of the losing team's captain to be displayed on a tzompantli.[21] In these contexts it appears that the tzompantli was used to display the losers' heads of this often highly ritualised game. Not all games resulted in this outcome, however, and for those that did it is surmised that these participants were often notable captives. An alternative theory is that it was the captain of the winning team who lost his head, but there is little evidence that this was the case.[22] Still, it is acknowledged that in Mesoamerican culture to be sacrificed was to be honored with feeding the gods.[23] Tula, the former Toltec capital, has a well-preserved tzompantli inscription on its ball court.

The association with ball courts is also reflected in the Popol Vuh, the famous religious, mythological and cultural account of the K'iche' Maya. When Hun Hunahpu, father of the Maya Hero Twins, was killed by the lords of the Underworld (Xibalba), his head was hung in a gourd tree next to a ball court.[24] The gourd tree is a clear representation of a "tzompantli", and the image of skulls in trees as if they were fruits is also a common indicator of a tzompantli and the associations with some of the game's metaphorical interpretations.[25]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tzompantli. |

Notes

- ↑ Palka (2000) pg 152

- ↑ Mendoza (2007) pg 397

- ↑ Mendoza (2007) pg 397

- ↑ Frances Karttunen. "Linguist list server". etymology of Tzompantli. Retrieved September 25, 2005.

- ↑ Nelson et al. (1992) p. 308

- ↑ Spencer (1982), pp.236-239

- ↑ Flannery (2003)

- ↑ Coe (2011) 196

- ↑ Mendoza (2007) 396

- ↑ Brandes (2009) p. 51

- ↑ Miller and Taube (1993), p.176.

- ↑ Coe (2011) pg. 195-196 or 210 in the 2015 edition

- ↑ Coe and Koontz (2008) p. 194

- ↑ Coe and Koontz (2008) pg 110

- ↑ Michael Harner (1977) p. 120

- ↑ Harner (1977) p. 122

- ↑ Ortíz de Montellano 1983

- ↑ Ruben Mendoza (2007) p. 407-408.

- ↑ Diaz del Castillo (1963)

- ↑ Levy (2009) pg 65

- ↑ Coe (2011) pg 195-196

- ↑ Joseph Campbell (1988) p. 108

- ↑ Coe and Koontz (2008) 204-205

- ↑ Coe (2011) p. 67

- ↑ Mendoza (2007)pg 418

References

- Mendoza, Ruben G. (2007). Richard J. Chacon; David H. Dye, eds. "The Divine Gourd Tree: Tzompantli Skull Racks, Decapitation Rituals, and Human Trophies in Ancient Mesoamerica". The Taking and Displaying of Human Body Parts as Trophies by Amerindians. New York: Springer Press: 400–443. ISBN 978-0-387-48300-9.

- Miller, Mary; Karl Taube (1993). The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05068-6.

- Spencer, C. S. (1982). The Cuicatlán Cañada and Monte Albán: A Study of Primary State Formation. New York: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-656680-1.

- Ortíz de Montellano; Bernard R. (1983). "Counting Skulls: Comment on the Aztec Cannibalism Theory of Harner-Harris". American Anthropologist. 85 (2): 403–406. doi:10.1525/aa.1983.85.2.02a00130.

- Coe, Michael D.; Rex Koontz (2008). Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs. New York: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28755-2.

- Coe, Michael D. (2011). The Maya. New York: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28902-0.

- Palka, Joel W. (2007). Historical Dictionary of Mesoamerica. Lanham: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0810837157.

- Harner, Michael (February 1977). "The Ecological Basis for Aztec Sacrifice". American Ethnologist. 4 (1): 117–135. doi:10.1525/ae.1977.4.1.02a00070. JSTOR 643526.

- Brandes, Stanley (2009). Skulls to the Living, Bread to the Dead: The Day of the Dead in Mexico and Beyond. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781405178709.

- Nelson, Ben A.; J. Andrew Darling; David A. Kice (December 1992). "Mortuary Practices and the Social Order at La Quemada, Zacatecas, Mexico". Latin American Antiquity. 3 (4): 298–315. doi:10.2307/971951.

- Campbell, Joseph (1988). The Power of Myth. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0385418867.

- Flannery, Kent V.; Joyce Marcus (July 2003). "The origin of war: New 14C dates from ancient Mexico". PNAS. 100 (20): 11801–11805. doi:10.1073/pnas.1934526100.

- Levy, Buddy (2009). Conquistador: Hernán Cortés, King Montezuma, and the Last Stand of the Aztecs. New York: Random House LLC. ISBN 9780553384710.

- Diaz del Castillo, Bernal (1963). Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España [The Conquest of New Spain]. Translated by J. M. Cohen. New York: Penguin Group. ISBN 978-0140441239.