Upnor Castle

| Upnor Castle | |

|---|---|

|

Upnor Castle on the River Medway | |

| Coordinates | 51°24′25″N 0°31′38″E / 51.406907°N 0.527114°ECoordinates: 51°24′25″N 0°31′38″E / 51.406907°N 0.527114°E |

| OS grid reference | TQ7585670574 |

| Built | 1559–67 |

| Built for | Royal Navy |

| Architect | Sir Richard Lee |

| Governing body | English Heritage |

| Type | Ancient Monument |

| Designated | 28 January 1960 |

| Reference no. | 1012980 |

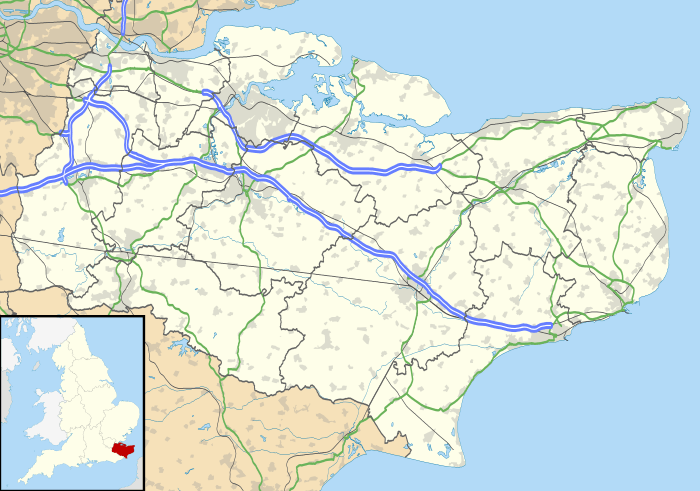

Upnor Castle location within Kent | |

Upnor Castle is an Elizabethan artillery fort located on the west bank of the River Medway in Kent. It is in the village of Upnor, opposite and a short distance downriver from the Chatham Dockyard, at one time a key naval facility. The fort was intended to protect both the dockyard and ships of the Royal Navy anchored in the Medway. It was constructed between 1559–67 on the orders of Elizabeth I, during a period of tension with Spain and other European powers. The castle consists of a two-storeyed main building protected by a curtain wall and towers, with a triangular gun platform projecting into the river. It was garrisoned by about 80 men with a peak armament of around 20 cannon of various calibres.

Despite its strategic importance, the castle and the defences of the Thames and Medway were badly neglected during the 17th century. The Dutch Republic mounted an unexpected naval raid in June 1667, and the Dutch fleet was able to breach the defences, capturing two warships and burning others at anchor in the river at Chatham, in one of the worst defeats suffered by the Royal Navy. Upnor Castle acquitted itself better than many of the other defensive sites along the upper Medway, despite its lack of provisioning. Gun fire from the fort and from adjoining emplacements forced a Dutch retreat after a couple of days, before they were able to burn the dockyard itself.

The raid exposed the weaknesses of the Medway defences and led to the castle losing its role as an artillery fortification. New and stronger forts were built further downriver over the following two centuries, culminating in the construction of massive casemated forts such as Garrison Point Fort, Hoo, and Darnet Forts. Upnor Castle became a naval ammunition depot, storing great quantities of gunpowder, ammunition, and cannon to replenish the warships that came to Chatham for repair and resupply. It remained in military use until as late as 1945. The castle was subsequently opened to the public and is now an English Heritage property.

History

Strategic context

The River Medway is a major tributary of the Thames, merging at an estuary about 35 miles (56 km) east of London. Its upper reaches from Rochester to the confluence with the Thames at Sheerness meander between sand and mud banks for about 10 miles (16 km). The water flows slowly without strong currents and is free of rocks, while the surrounding hills provide shelter from the south-west wind. These characteristics made the section of the river below Rochester Bridge a desirable anchorage for large ships, as they could be anchored safely and grounded for repairs. The complexity of the channel's navigation also provided it with defensive advantages.[1]

During Henry VIII's reign, the upper Medway gradually became the principal anchorage for ships of the Royal Navy while they were "in ordinary," or out of commission. They were usually stripped of their sails and rigging while in this state and the opportunity was taken to refit and repair them. Storehouses and servicing facilities were built in the Medway towns of Gillingham and Chatham which eventually became the nucleus of the Chatham Dockyard. By the time Elizabeth I came to the throne in 1558, most of the royal fleet used this section of the Medway, known as Chatham and Gillingham Reaches, as an anchorage.[2]

Although the Thames had been defended from naval attack since Henry VIII's time, when five blockhouses were built as part of the Device Forts chain of coastal defences, there were no equivalents on the Medway. Two medieval castles – Rochester Castle and Queenborough Castle – existed along the river's south bank, but both were intended to defend landward approaches and were of little use for defence. There was thus a pressing need for proper defences to protect the vulnerable ships and shore facilities on the upper Medway.[2]

Construction

Upnor Castle was commissioned in 1559 by order of Queen Elizabeth and her Privy Council. Six "indifferent persons" chose a site opposite St Mary's Creek in Chatham, on 6 acres (24,000 m2) of land belonging to a Thomas Devinisshe of Frindsbury. It was acquired by the Crown – possibly compulsorily purchased[3] – for the sum of £25. Military engineer Sir Richard Lee was given the task of designing the new fortification, but he appears to have been fully occupied with working on the defences of Berwick-upon-Tweed, and the project was carried out by others to his designs. His deputy Humphrey Locke took the role of overseer, surveyor, and chief carpenter, while Richard Watts, the former Rochester mayor and victualler to the navy, managed the project on a day-to-day basis and handled the accounting.[2]

The castle's original appearance differed significantly from that of today. The arrow-shaped Water Bastion facing into the Medway and the main block behind it were part of the original design. There were also towers at either end of the water frontage, though these were subsequently replaced by towers of a different design. The gatehouse and moat were later additions. A number of derelict buildings in Rochester Castle, Aylesford, and Bopley were pulled down to provide stone for the castle. The main structure had been completed by 1564, but it took another three years and an infusion of extra funds to finish the project. The total cost came to £4,349.[4]

Improvements and repairs

During the late 16th century, tensions grew between Protestant England and Catholic Spain, leading ultimately to the undeclared Anglo-Spanish War of 1585–1604. Spain was in a strong position to attack the south of England from its possessions in the Spanish Netherlands. New fortifications were erected along the Medway, including a chain stretched across the width of the river below Upnor Castle. The castle itself was poorly manned until Lord High Admiral Charles Howard, 1st Earl of Nottingham highlighted this and recommended that the garrison should be increased. By 1596, it was garrisoned by eighty men who were each paid eight pence per day (equivalent to £6 today).[5]

Continued fears of a Spanish incursion led to the castle's defences being strengthened between 1599–1601 at the instigation of Sir John Leveson. An arrowhead-shaped timber palisade was erected in front of the Water Bastion to block any attempted landings there. An enclosing ditch some 5.5 metres (18 ft) deep and 9.8 metres (32 ft) wide was dug around the castle. Flanking turrets were constructed to protect the bastion on the site of the present north and south towers. The bastion itself was raised and a high parapet was added to its edge. A gatehouse and drawbridge were also built to protect the castle's landward side.[6]

A survey conducted in 1603 recorded that Upnor Castle had 20 guns of various calibres, plus another 11 guns split between two sconces or outworks, known as Bay and Warham Sconces. The castle's armament consisted of a demi-cannon, 7 culverin, 5 demi-culverin, a minion, a falconet, a saker, and four fowlers with two chambers each. Bay Sconce was armed with 4 demi-culverin, while Warham Sconce had 2 culverin and 5 demi-culverin.[7] Eighteen guns were recorded as being mounted in the castle twenty years later. The garrison's armament included 34 longbows, an indication that archery was still of military value even at this late date. By this time, however, the castle was in a state of disrepair. The drawbridge and its raising mechanism were broken, the gun platforms needed repairs, and the courtyard wall had collapsed. A new curtain wall had to be built to protect the landward side of the castle.[8] The foundations of Warham Sconce were reported to have been washed away by the tide, and it appears that both sconces were allowed to fall into ruin.[9]

Upnor Castle fell into Parliamentary hands without a fight when the English Civil War broke out in 1642, and was subsequently used to intern Royalist officers. In May 1648, a Royalist uprising took place in Kent and Essex, with the royalists seizing a number of towns, including Gravesend, Rochester, Dover, and Maidstone. The Royalists were defeated in the Battle of Maidstone on 1 June, and the castle was restored to Parliamentary hands. Parliamentary commander-in-chief Sir Thomas Fairfax inspected the castle and ordered further repairs and strengthening of the gun platforms. It appears that the height of the gatehouse was also increased at this time, and the north and south towers were built up. They appear to have been left open at the back (on the landward side), but this was remedied in 1653 in the course of further repairs, making them suitable for use as troop accommodation.[8]

Raid on the Medway

The castle only saw action once in its history, during the Dutch Raid on the Medway in June 1667, part of the Second Anglo-Dutch War. The Dutch, under the nominal command of Lieutenant-Admiral Michiel de Ruyter, bombarded and captured the town of Sheerness, sailed up the Thames to Gravesend, then up the Medway to Chatham.[8] They made their way past the chain that was supposed to block the river, sailed past the castle, and towed away HMS Royal Charles and Unity, as well as burning other ships at anchor.[10] The Dutch anchored in the Medway overnight on 12 June, while the Duke of Albemarle took charge of the defences and ordered the hasty construction of an eight-gun battery next to Upnor Castle, using guns taken from Chatham. The castle's guns, the garrison's muskets, and the new battery were all used to bombard the Dutch ships when they attempted a second time to sail past Upnor to Chatham. The Dutch were able to burn some more ships in the anchorage, but they were unable to make further progress and had to withdraw.[10] The outcome of the raid has been described as "the worst naval defeat England has ever sustained."[11]

The castle had acquitted itself well in the eyes of contemporary observers, despite its inability to prevent the raid, and the dedication of its garrison was praised.[10] The pro-government London Gazette reported that "they were so warmly entertained by Major Scot, who commanded there [at Upnor], and on the other side by Sir Edward Spragg, from the Battery at the Shoare, that after very much Dammage received by them in the shattering of their ships, in sinking severall of their Long Boats manned out by them, in the great number of their Men kill'd, and some Prisoners taken, they were at the last forced to retire."[12] Military historian Norman Longmate observes tartly, "in presenting damning facts in the most favourable light Charles [II's] ministers were unsurpassed."[13] Samuel Pepys, secretary of the Navy Board, got closer to the truth when he noted in his diary that the castle's garrison were poorly provisioned: "I do not see that Upnor Castle hath received any hurt by them though they played long against it; and they themselves shot till they had hardly a gun left upon the carriages, so badly provided they were."[10]

Usage as a magazine and naval facility

Upnor Castle had been neglected previously, but the Dutch attack prompted the government to order that it be maintained "as a fort and place of strength".[10] In the end, the raid marked the end of the castle's career as a fortress. New and more powerful forts were built farther down the Medway and on the Isle of Grain with the aim of preventing enemies reaching Chatham, thus making the castle redundant. It was converted into "a Place of Stores and Magazines" in 1668 with a new purpose of supplying munitions to naval warships anchored in the Medway or the Swale. Guns, gun carriages, shot, and gunpowder were stored in great quantities within the main building of the castle, which had to be increased in height and its floors reinforced to accommodate the weight. By 1691, it was England's leading magazine, with 164 iron guns, 62 standing carriages, 100 ships' carriages, 7,125 pieces of iron shot, over 200 muskets of various types, 77 pikes, and 5,206 barrels of powder. This was considerably more than was held at the next largest magazine, the Tower of London.[14]

In 1811 a new magazine building was erected a little way downstream from the castle, relieving pressure on the castle. Upnor Castle ceased to be used as a storage magazine after 1827 and was converted into an Ordnance Laboratory (i.e. a workshop for filling explosive shells with gunpowder). Further storage space was required, and six hulks were moored alongside to serve as floating magazines; they remained even after a further magazine had been built ashore (1857). These storage problems were only alleviated when a further five large magazines, guarded by a barracks, were built inland at Chattenden (these were linked to Upnor via a 2 ft 6in (76 cm) narrow-gauge line built for steam locomotives).[15] In 1891, the castle and its associated depot came under the full control of the Admiralty, ending an arrangement in which the War Office had managed the site with the Admiralty providing the funding. In 1899 it was noted that the castle was being used to store dry guncotton (a highly-flammable and dangerous explosive), while the less dangerous 'wet guncotton' form was kept on board the ever-present hulks moored nearby. This practice ceased soon afterwards, specialist storage magazines having been built alongside Chattenden at Lodge Hill.[16]

After the First World War, Upnor became a Royal Naval Armaments Depot (RNAD), one of a group of such facilities around the country. The castle and magazine were used for a time as a proofyard for testing firearms and explosives.[15]

The castle remained in military ownership, but it became more of a museum from the 1920s onwards.[17] During the Second World War, the castle was still in service as part of the Magazine Establishment and was damaged by two enemy bombs which fell in 1941.[15] The bombing dislodged pieces of plaster in the castle's south tower and gatehouse, under which were discovered old graffiti, including a drawing of a ship dated to around 1700.[17]

The castle today

Following the end of the war in 1945, the Admiralty gave approval for Upnor Castle to be used as a Departmental Museum and to be opened to the public.[17] It subsequently underwent a degree of restoration.[15] The castle was scheduled as an Ancient Monument in January 1960 and is currently managed by English Heritage. It remains part of the Crown Estate.[18]

Description

Upnor Castle's buildings were constructed from a combination of Kentish ragstone and ashlar blocks, plus red bricks and timber. Its main building is a two-storeyed rectangular block that measures 41 m (135 ft) by 21 m (69 ft), aligned in a north-east/south-west direction on the west bank of the Medway.[18] Later known as the Magazine, it has been changed considerably since its original construction. It would have included limited barrack accommodation, possibly in a small second storey placed behind gun platforms on the roof. After the building was converted into a magazine in 1668 many changes were made which have obscured the earlier design.[19] The second storey appears to have been extended across the full length of the building, covering over the earlier rooftop gun platforms. This gave more room for storage in the interior. The ground floor was divided into three compartments with a woodblock floor and copper-sheeted doors to reduce the risk of sparks.[20] Further stores were housed on the first floor, with a windlass to raise stores from the waterside.[19]

A circular staircase within the building gives access to the castle's main gun platform or water bastion, a low triangular structure projecting into the river. The castle's main armament was mounted here in the open air; this is now represented by six mid-19th century guns that are still on their original carriages.[18] There are nine embrasures in the bastion, six facing downstream and three upstream, with a rounded parapet designed to deflect shot.[21] The water bastion was additionally protected by a wooden palisade that follows its triangular course a few metres further out in the river. The present palisade is a modern recreation of the original structure.[18]

A pair of towers stand on the river's edge a short distance on either side from the main building. They were originally two-storyed open-backed structures with gun platforms situated on their first floors, providing flanking fire down the line of the ditch around the castle's perimeter. They were later adapted for use as accommodation, with their backs closed with bricks and the towers increased in height to provide a third storey. Traces of the gun embrasures can still be seen at the point where the original roofline was.[22] The South Tower was said to have been for the use of the castle's governor, though their lack of comfort meant that successive governors declined to live there. The two towers are linked to the main building by a crenallated curtain wall where additional cannon were emplaced in two embrasures on the north parapet and one on the south.[23]

The castle's principal buildings are situated on the east side of a rectangular courtyard within which stand two large Turkey oaks, said to have been grown from acorns brought from Crimea after the Crimean War.[22] A stone curtain wall topped with brick surrounds the courtyard, standing about 1 m (3.3 ft) thick and 4 m (13 ft) high. The courtyard is entered on the north-western side through a four-storeyed gatehouse with gun embasures for additional defensive strength.[18] It was substantially rebuilt in the 1650s after being badly damaged in a 1653 fire, traces of which can still be seen in the form of scorched stones on the first floor walls.[22] A central gateway with a round arch leads into a passage that gives access to the courtyard. Above the gateway is a late 18th century clock that was inserted into the existing structure. A wooden bellcote was added in the early 19th century and a modern flagpole surmounts the building.[18]

The curtain wall is surrounded by a dry ditch which was originally nearly 10 m (33 ft) wide by 5.5 m (18 ft) deep, though it has since been partially infilled. Visitors to the castle crossed a drawbridge, which is no longer extant, to reach the gatehouse. A secondary entrance to the castle is provided by a sally port in the north wall. On the inside of the curtain wall the brick foundations of buildings can still be seen. These were originally lean-to structures, constructed in the 17th century to provide storage facilities for the garrison.[18]

|

Other associated buildings

Standing to the west of the castle, Upnor Castle House was built in the mid-17th century as accommodation for the Storekeeper, the officer in charge of the magazine. Expanded in the 18th century, it is now a private residence.[24]

A short distance to the south-west of the castle is a barracks block and associated storage buildings, constructed soon after 1718. Built to replace the original barrack accommodation within the castle when it was redeveloped to convert it into a magazine, it has changed little externally in the last 300 years. It is a rare surviving example of an 18th-century building of this type and was one of the first distinct barracks to be built in England.[25]

Depot buildings formerly associated with the castle still survive in the area immediately to the north-east. The earliest is a gunpowder magazine of 1857 (built to the same design as the 1810 magazine, which formerly stood alongside to the south but was demolished in the 1960s; these buildings had space for 33,000 barrels of powder between them).[26] Between the magazines and the castle a Shifting House (for examining powder) had been built in 1811;[27] both it and an adjacent shell store of 1857 were likewise demolished in 1964. They were constructed on top of earlier gun emplacements, of which earthwork traces can still be seen in the form of a broad bank running north-east from the castle towards the depot.[18] A further four shell stores were built further to the north, together with other munitions stores, several of which remain. The Depot compound continued in Ministry of Defence hands until 2014, after which the area was due to be redeveloped as housing (with the surviving military buildings refurbished for light industrial use).[28]

References

- ↑ Heritage, English; Saunders, A. D. (1 January 1985). Upnor Castle: Kent. English Heritage. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-85074-039-1.

- 1 2 3 Saunders, p. 6

- ↑ Reynolds, Susan (1 March 2010). Before Eminent Domain: Toward a History of Expropriation of Land for the Common Good. Univ of North Carolina Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-8078-9586-3.

- ↑ Saunders, p. 7

- ↑ Saunders, p. 10

- ↑ Saunders, pp. 10–11

- ↑ Saunders, p. 11

- 1 2 3 Saunders, p. 13

- ↑ Rogers, Philip George (1970). The Dutch in the Medway. Oxford University Press. p. 56. ISBN 9780192151858.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Saunders, p. 14

- ↑ Vere, Francis (1955). Salt in Their Blood: The Lives of Famous Dutch Admirals. Cassell. p. 145. OCLC 1626646.

- ↑ The London Gazette, 13–17 June 1667, no. 165, p. 2

- ↑ Longmate, Norman (30 September 2011). Island Fortress: The Defence of Great Britain 1606–1945. Random House. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-4464-7577-5.

- ↑ Saunders, p. 15

- 1 2 3 4 Saunders, p. 21

- ↑ Evans, David (2006). Arming the Fleet: The Development of the Royal Ordnance Yards 1770-1945. Gosport, Hants.: Explosion! Museum (in association with English Heritage).

- 1 2 3 O’Neil, B. H. St. J.; Evans, S. (1952). "Upnor Castle, Kent". Archaeologia Cantiana. 65: 1–11.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Heritage List for England – Upnor Castle". English Heritage. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- 1 2 Saunders, p. 30

- ↑ Saunders, p. 31

- ↑ Saunders, p. 33

- 1 2 3 Saunders, p. 27

- ↑ Saunders, p. 29

- ↑ "Upnor Conservation Area Appraisal 2004" (PDF). Medway council. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- ↑ Saunders, p. 22

- ↑ "Listed building description". Historic England. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- ↑ "Listed structure description". Historic England. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- ↑ "Lower Upnor Depot". Hume Planning Consultancy. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Upnor Castle. |

- Upnor Castle – page at English Heritage

- Information about the castle

- History of Upnor Castle

- Chatham's World Heritage Site application – including Upnor Castle