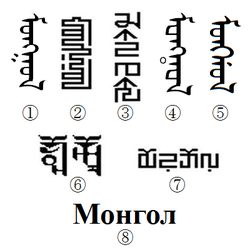

Mongolian script

| Mongolian | |

|---|---|

|

Example text | |

| Type | |

| Languages |

Mongolian language Manchu language (obsolete) Evenki language |

Time period | ca.1204 – today |

Parent systems | |

Child systems |

Manchu alphabet Oirat alphabet (Clear script) Buryat alphabet Galik alphabet Evenki alphabet Xibe alphabet |

Sister systems | Old Uyghur alphabet |

| Direction | Top-to-bottom |

| ISO 15924 |

Mong, 145 |

Unicode alias | Mongolian |

| |

The classical Mongolian script (in Mongolian script: ᠮᠣᠩᠭᠣᠯᠪᠢᠴᠢᠭ Mongγol bičig; in Mongolian Cyrillic: Монгол бичиг Mongol bichig), also known as Hudum Mongol bichig, was the first writing system created specifically for the Mongolian language, and was the most successful until the introduction of Cyrillic in 1946. Derived from Sogdian, Mongolian is a true alphabet, with separate letters for consonants and vowels. The Mongolian script has been adapted to write languages such as Oirat and Manchu. Alphabets based on this classical vertical script are used in Inner Mongolia and other parts of China to this day to write Mongolian, Xibe and, experimentally, Evenki.

History

The Mongolian vertical script developed as an adaptation of the Sogdian to the Mongolian language. From the seventh and eighth to the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the Mongolian language separated into southern, eastern and western dialects. The principal monuments of the middle period are: in the eastern dialect, the famous text The Secret History of the Mongols, monuments in the square script, materials of the Chinese-Mongolian glossary of the fourteenth century, and materials of the Mongolian language of the middle period in Chinese transcription, etc.; in the western dialect, materials of the Arab-Mongolian and Persian-Mongolian dictionaries, Mongolian texts in Arabic transcription, etc. The main features of the period are that the vowels ï and i had lost their phonemic significance, creating the i phoneme (in Chahar dialect, the Standard Mongolian in Inner Mongolia, they're still distinct); intervocal consonants γ/g, b/w had disappeared and the preliminary process of the formation of Mongolian long vowels had begun; the initial h was preserved in many words; grammatical categories were partially absent, etc. The development over this period explains why Mongolian script looks like a vertical Arabic script (in particular the presence of the dots system).

Eventually, minor concessions were made to the differences between the Uyghur and Mongol languages: In the 17th and 18th centuries, smoother and more angular versions of tsadi became associated with [dʒ] and [tʃ] respectively, and in the 19th century, the Manchu hooked yodh was adopted for initial [j]. Zain was dropped as it was redundant for [s]. Various schools of orthography, some using diacritics, were developed to avoid ambiguity.

Mongolian is written vertically. The Uyghur script and its descendants—Mongolian, Oirat Clear, Manchu, and Buryat—are the only vertical scripts written from left to right. This developed because the Uyghurs rotated their Sogdian-derived script, originally written right to left, 90 degrees counterclockwise to emulate Chinese writing, but without changing the relative orientation of the letters.[1]

Teaching

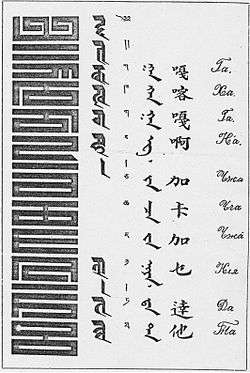

Mongols learned their script as a syllabary, dividing the syllables into twelve different classes, based on the final phonemes of the syllables, all of which ended in vowels.[2] The Manchus followed the same syllabic method when learning Manchu script, also with syllables divided into twelve different classes[3][4][5] based on the final phonemes of the syllables.

Despite the alphabetic nature of its script, Manchu was not taught phoneme by phoneme per letter like western languages are, rather, Manchu children were taught to memorize all the syllables in the Manchu language separately as they learned to write, like Chinese characters. Manchus when learning, instead of saying l, a---la; l, o---lo; etc., were taught at once to say la, lo, etc. Many more syllables than are contained in their syllabary might have been formed with their letters, but they were not accustomed to arrange them otherwise than as they there stand. They made, for instance, no such use of the consonants I, m, n, and r, as westerners do when they called them liquid; hence if the Manchu letters s, m, a, r, t, be joined in that order as a Manchu would not able to pronounce them as English speaking people pronounce the word "smart".[6] Manchu children were taught the language via the syllabic method.[7]

Some westerners learn the script in an alphabetic manner instead.

Today, the opinion on whether it is alphabet or syllabic in nature is still split between different experts. In China, it is considered syllabic and Manchu is still taught in this manner. The alphabetic approach is used mainly by foreigners who want to learn the language. Studying Manchu script as a syllabary takes a longer time.[8][9]

Name

The Traditional Mongolian script is known by a wide variety of names. Due to its shape like Uighur script, it became known as the Uighurjin Mongol script (Mongolian: Уйгуржин монгол бичиг). During the communist era, when Cyrillic became the official script for the Mongolian language, the traditional script became known as the Old Mongol script (Mongolian: Хуучин монгол бичиг), in contrast to the New script (Mongolian: Шинэ үсэг), referring to Cyrillic. The name Old Mongol script stuck, and it is still known as such among the older generation, who didn't receive education in the new script.

Letters

The traditional or classical Mongolian alphabet, sometimes called Hudum 'traditional' in Oirat in contrast to the Clear script (Todo 'exact'), is the original form of the Mongolian script used to write the Mongolian language. It does not distinguish several vowels (o/u, ö/ü, final a/e) and consonants (t/d, k/g, sometimes ž/y) that were not required for Uyghur, which was the source of the Mongol (or Uyghur-Mongol) script.[1] The result is somewhat comparable to the situation of English, which must represent ten or more vowels with only five letters and uses the digraph th for two distinct sounds. Ambiguity is sometimes prevented by context, as the requirements of vowel harmony and syllable sequence usually indicate the correct sound. Moreover, as there are few words with an exactly identical spelling, actual ambiguities are rare for a reader who knows the orthography.

Letters have different forms depending on their position in a word: initial, medial, or final. In some cases, additional graphic variants are selected for visual harmony with the subsequent character.

Note that in some browsers, letters are rotated 90° counterclockwise. If the letter for 'a' looks like a 'W' and not a 'Σ', rotate the letters 90° clockwise.

| Characters | Transliteration | Notes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| alone | initial | medial | final | Latin | Cyrillic | IPA | ||

| ᠠ | ᠠ | ᠠ | ᠠᠠ᠋ | a | А | a | Distinction usually by vowel harmony (see also q/γ and k/g below) | |

| ᠡ | ᠡ | e | Э | e | ||||

| ᠢ | ᠢ | ᠢ[note 1] ᠢ᠋[note 2] | ᠢ | i, yi | И, Й, Ы, Ь | i, ji | At end of word today often absorbed into preceding syllable | |

| ᠣ | ᠣ | ᠣ | ᠣ | o, u | О, У | o, ʊ | Distinction depending on context. | |

| ᠥ | ᠥ | ᠥᠥ᠋ | ᠥᠥ᠋ | ö, ü | Ө, Ү | œ, u | Distinction depending on context. | |

| ᠨ | ᠨ | ᠨ[note 3] ᠨ᠋[note 4] | ᠨᠨ᠌ | n | Н | n | Distinction from medial and final a/e by position in syllable sequence. | |

| ᠩ | ᠩ | ᠩ | ng | Н, НГ | ŋ | Only at end of word (medial for composites).

Transcribes Tibetan ང; Sanskrit ङ. | ||

| ᠪ | ᠪ | ᠪ | ᠪᠪ᠋ | b | Б, В | b, v | In classical Mongolian v is used only for transcribing foreign words, so most "В (V)" in Cyrillic Mongolian correspond to "Б (B)" in Classical Mongolian. | |

| ᠫ | ᠫ | ᠫ | ᠫ | p | П | p | Only at the beginning of Mongolian words.

Transcribes Tibetan པ; | |

| ᠬ | ᠬ | ᠬ | ᠬ | q | Х | x | Only with back vowels. The "final" version only appears when followed by an a written detached from the word. | |

| ᠭ | ᠭ | ᠭᠭ᠋ | ᠭᠭ᠋ | γ | Г | g, ɢ | Only with back vowels.

Between vowels pronounced as a long vowel in oral Mongolian.[note 5] | |

| ᠭ᠍ | ᠭ᠍ | k | Х | x | Only with front vowels, but 'ki/gi' can occur in both front and back vowel words

Word-finally only g, not k. g between vowels pronounced as long vowel.[note 6] | |||

| ᠭ᠌ | g | Г | g, ɢ | |||||

| ᠮ | ᠮ | ᠮ | ᠮ | m | М | m | ||

| ᠯ | ᠯ | ᠯ | ᠯ | l | Л | l | ||

| ᠰ | ᠰ | ᠰ | ᠰ | s | С | s | ||

| ᠱ | ᠱ | ᠱ | ᠱ | š | Ш | ʃ | ||

| ᠲᠳ | ᠲ | ᠲᠳ᠋ | ᠳ | t, d | Т, Д | t, d | Distinction depending on context. | |

| ᠴ | ᠴ | ᠴ | č | Ч, Ц | tʃʰ, tsʰ | Distinction between /tʃʰ/ and /tsʰ/ in Khalkha Mongolian. | ||

| ᠵ | ᠵ | ᠵ | j | Ж, З | tʃ, ts | Distinction by context in Khalkha Mongolian. | ||

| ᠶ | ᠶ | ᠶ | ᠶ | y | -Й, Е*, Ё*, Ю*, Я* | j | ||

| ᠷ | ᠷ | ᠷ | ᠷ | r | Р | r | Not normally at the beginning of words.[note 7] | |

| ᠸ | ᠸ | ᠸ | v | В | v | Used to transcribe foreign words (Originally used to transcribe Sanskrit व) | ||

| ᠹ | ᠹ | ᠹ | ᠹ | f | Ф | f | Used to transcribe foreign words | |

| ᠺ | ᠺ | ᠺ | k | К | kʰ | Used to transcribe foreign words (Originally used to transcribe Tibetan /g/ ག; Sanskrit ग) | ||

| ᠻ | ᠻ | ᠻ | ᠻ | ḳ | К | kʰ | Used to transcribe foreign words (Originally used to transcribe Tibetan /kʰ/ ཁ; Sanskrit ख) | |

| ᠼ | ᠼ | ᠼ | (c) | (ц) | ts | Used to transcribe foreign words (Originally used to transcribe Tibetan /ts'/ ཚ; Sanskrit छ) | ||

| ᠽ | ᠽ | ᠽ | (z) | (з) | z | Used to transcribe foreign words (Originally used to transcribe Tibetan /dz/ ཛ; Sanskrit ज) | ||

| ᠾ | ᠾ | ᠾ | (h) | (г, х) | h | Used to transcribe foreign words (Originally used to transcribe Tibetan /h/ ཧ, ྷ; Sanskrit ह) | ||

| ᠿ | ᠿ | (ř) | (-,-) | Transcribes Chinese 'ri' - used in Inner Mongolia | ||||

| ᡁ | ᡁ | (zh) | (-,-) | ʈ͡ʂ | Transcribes Chinese 'zhi' - used in Inner Mongolia | |||

| ᡂ | ᡂ | (chi) | (-,-) | Transcribes Chinese 'chi' - used in Inner Mongolia | ||||

Notes:

- ↑ Following a consonant, Latin transliteration is i.

- ↑ Following a vowel, Latin transliteration is yi, with rare exceptions like naim ("eight") or Naiman.

- ↑ Character for back of syllable (<vowel>-n).

- ↑ Character for front of syllable (n-<vowel>).

- ↑ Examples: qa-γ-an (khan) is shortened to qaan unless reading classical literary Mongolian. Some exceptions like tsa-g-aan ("white") exist.

- ↑ Example: de-g-er is shortened to deer. Some exceptions like ügüi ("no") exist.

- ↑ Transcribed foreign words usually get a vowel prepended. Example: Transcribing Русь (Russia) results in Oros.

Examples

| Manuscript | Type | Unicode | Transliteration (first word) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

ᠸᠢᠺᠢᠫᠧᠳᠢᠶᠠ᠂ ᠴᠢᠯᠦᠭᠡᠲᠦ ᠨᠡᠪᠲᠡᠷᠬᠡᠢ ᠲᠣᠯᠢ ᠪᠢᠴᠢᠭ ᠪᠣᠯᠠᠢ᠃ | ᠸ v |

| ᠢ i | |||

| ᠭ᠍ k | |||

| ᠢ i | |||

| ᠫ p | |||

| ᠡ e | |||

| ᠲ d | |||

| ᠢ i | |||

| ᠶ y | |||

| ᠠ a |

- Transliteration: Vikipediya čilügetü nebterkei toli bičig bolai.

- Cyrillic: Википедиа чөлөөт нэвтэрхий толь бичиг болой.

- Transcription: Vikipedia chölööt nevterkhii toli bichig boloi.

- Gloss: Wikipedia free omni-profound mirror scripture is.

- Translation: Wikipedia is the free encyclopedia.

Child Systems

The Mongol script has been the basis of alphabets for several languages. First, after overcoming the Uyghur script ductus, it was used for Mongolian itself.

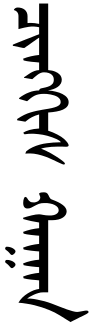

Clear script (Oirat alphabet)

In 1648, the Oirat Buddhist monk Zaya-pandita Namkhaijamco created this variation with the goals of bringing the written language closer to the actual pronunciation of Oirat and making it easier to transcribe Tibetan and Sanskrit. The script was used by the Kalmyks of Russia until 1924, when it was replaced by the Cyrillic alphabet. In Xinjiang, China, the Oirat people still use it.

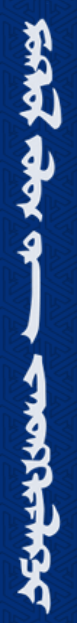

Manchu alphabet

The Manchu alphabet was developed from the Mongolian script in the early 17th century to write the Manchu language. A variant is still used to write Xibe. It is also used for Daur. Its folded variant may for example be found on Chinese Qing seals.

Vagindra alphabet

Another alphabet, sometimes called Vagindra or Vaghintara, was created in 1905 by the Buryat monk Agvan Dorjiev (1854–1938). It was also meant to reduce ambiguity, and to support the Russian language in addition to Mongolian. The most significant change, however, was the elimination of the positional shape variations. All letters were based on the medial variant of the original Mongol alphabet. Fewer than a dozen books were printed using it.

Evenki alphabet

The Qing dynasty Qianlong Emperor erroneously identified the Khitan people and their language with the Solons, leading him to use the Solon language (Evenki) to "correct" Chinese character transcriptions of Khitan names in the History of Liao in his "Imperial Liao Jin Yuan Three Histories National Language Explanation" (欽定遼金元三史國語解/钦定辽金元三史国语解 Qīndìng Liáo Jīn Yuán Sānshǐ Guóyǔjiě) project. The Evenki words were written in the Manchu script in this work.

In the 1980s, an experimental alphabet for Evenki was created.

Additional characters

Galik characters

In 1587, the translator and scholar Ayuush Güüsh (Аюуш гүүш) created the Galik alphabet (Али-гали), inspired by the third Dalai Lama, Sonam Gyatso. It primarily added extra characters for transcribing Tibetan and Sanskrit terms when translating religious texts, and later also from Chinese. Some of those characters are still in use today for writing foreign names (compare table above).[10]

Unicode

Mongolian script was added to the Unicode Standard in September, 1999 with the release of version 3.0.

Blocks

The Unicode block for Mongolian is U+1800–U+18AF. It includes letters, digits and various punctuation marks for Hudum Mongolian, Todo Mongolian, Xibe (Manchu), Manchu proper, and Ali Gali, as well as extensions for transcribing Sanskrit and Tibetan.

| Mongolian[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+180x | ᠀ | ᠁ | ᠂ | ᠃ | ᠄ | ᠅ | ᠆ | ᠇ | ᠈ | ᠉ | ᠊ | FV S1 |

FV S2 |

FV S3 |

MV S |

|

| U+181x | ᠐ | ᠑ | ᠒ | ᠓ | ᠔ | ᠕ | ᠖ | ᠗ | ᠘ | ᠙ | ||||||

| U+182x | ᠠ | ᠡ | ᠢ | ᠣ | ᠤ | ᠥ | ᠦ | ᠧ | ᠨ | ᠩ | ᠪ | ᠫ | ᠬ | ᠭ | ᠮ | ᠯ |

| U+183x | ᠰ | ᠱ | ᠲ | ᠳ | ᠴ | ᠵ | ᠶ | ᠷ | ᠸ | ᠹ | ᠺ | ᠻ | ᠼ | ᠽ | ᠾ | ᠿ |

| U+184x | ᡀ | ᡁ | ᡂ | ᡃ | ᡄ | ᡅ | ᡆ | ᡇ | ᡈ | ᡉ | ᡊ | ᡋ | ᡌ | ᡍ | ᡎ | ᡏ |

| U+185x | ᡐ | ᡑ | ᡒ | ᡓ | ᡔ | ᡕ | ᡖ | ᡗ | ᡘ | ᡙ | ᡚ | ᡛ | ᡜ | ᡝ | ᡞ | ᡟ |

| U+186x | ᡠ | ᡡ | ᡢ | ᡣ | ᡤ | ᡥ | ᡦ | ᡧ | ᡨ | ᡩ | ᡪ | ᡫ | ᡬ | ᡭ | ᡮ | ᡯ |

| U+187x | ᡰ | ᡱ | ᡲ | ᡳ | ᡴ | ᡵ | ᡶ | ᡷ | ||||||||

| U+188x | ᢀ | ᢁ | ᢂ | ᢃ | ᢄ | ᢅ | ᢆ | ᢇ | ᢈ | ᢉ | ᢊ | ᢋ | ᢌ | ᢍ | ᢎ | ᢏ |

| U+189x | ᢐ | ᢑ | ᢒ | ᢓ | ᢔ | ᢕ | ᢖ | ᢗ | ᢘ | ᢙ | ᢚ | ᢛ | ᢜ | ᢝ | ᢞ | ᢟ |

| U+18Ax | ᢠ | ᢡ | ᢢ | ᢣ | ᢤ | ᢥ | ᢦ | ᢧ | ᢨ | ᢩ | ᢪ | |||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

The Mongolian Supplement block (U+11660–U+1167F) was added to the Unicode Standard in June, 2016 with the release of version 9.0:

| Mongolian Supplement[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1166x | 𑙠 | 𑙡 | 𑙢 | 𑙣 | 𑙤 | 𑙥 | 𑙦 | 𑙧 | 𑙨 | 𑙩 | 𑙪 | 𑙫 | 𑙬 | |||

| U+1167x | ||||||||||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Font issues

Although the Mongolian script has been defined in Unicode since 1999, there was no native support for Unicode Mongolian from the major vendors until the release of the Windows Vista operating system in 2007 and fonts need to be installed in Windows XP and Windows 2000 to show properly, and so Unicode Mongolian is not yet widely used. In China, legacy encodings such as the Private Use Areas (PUA) Unicode mappings and GB18030 mappings of the Menksoft IMEs (espc. Menksoft Mongolian IME) are more commonly used than Unicode for writing web pages and electronic documents in Mongolian.

The inclusion of a Unicode Mongolian font and keyboard layout in Windows Vista has meant that Unicode Mongolian is now gradually becoming more popular, but the complexity of the Unicode Mongolian encoding model and the lack of a clear definition for the use variation selectors are still barriers to its widespread adoption, as is the lack of support for inline vertical display. As of 2015 there are no fonts that successfully display all of Mongolian correctly when written in Unicode. A report published in 2011 revealed many shortcomings with automatic rendering in all three Unicode Mongolian fonts the authors surveyed, including Microsoft's Mongolian Baiti.[11]

Furthermore, Mongolian language support has suffered from buggy implementations: the initial version of Microsoft's Mongolian Baiti font (version 5.00) was, in the supplier's own words, "almost unusable",[12] and as of 2011 there remain some serious bugs with the rendering of suffixes in Mozilla Firefox.[13] Other fonts, such as MonoType's Mongol Usug and Myatav Erdenechimeg's MongolianScript, suffer even more serious bugs.[11]

In January 2013, Menksoft released several OpenType Mongolian fonts, delivered with its Menksoft Mongolian IME 2012. These fonts strictly follow Unicode standard, i.e. bichig is no longer realized as "B+I+CH+I+G+FVS2" (incorrect) but "B+I+CH+I+G" (correct), which is not done by Microsoft and Founder's Mongolian Baiti, MonoType's Mongol Usug, or Myatav Erdenechimeg's MongolianScript.[14] However, due to the impact of Mongolian Baiti, many still use the Microsoft defined incorrect realization "B+I+CH+I+G+FVS2", which results in an incorrect rendering in correctly-designed fonts like Menk Qagan Tig.

References

- 1 2 György Kara, "Aramaic Scripts for Altaic Languages", in Daniels & Bright The World's Writing Systems, 1994.

- ↑ Chinggeltei. (1963) A Grammar of the Mongol Language. New York, Frederick Ungar Publishing Co. p. 15.

- ↑ Translation of the Ts'ing wan k'e mung, a Chinese Grammar of the Manchu Tartar Language; with introductory notes on Manchu Literature: (translated by A. Wylie.). Mission Press. 1855. pp. xxvii–.

- ↑ Shou-p'ing Wu Ko (1855). Translation (by A. Wylie) of the Ts'ing wan k'e mung, a Chinese grammar of the Manchu Tartar language (by Woo Kĭh Show-ping, revised and ed. by Ching Ming-yuen Pei-ho) with intr. notes on Manchu literature. pp. xxvii–.

- ↑ http://www.dartmouth.edu/~qing/WEB/DAHAI.html

- ↑ Meadows 1849, p. 3.

- ↑ Saarela 2014, p. 169.

- ↑ Gertraude Roth Li (2000). Manchu: a textbook for reading documents. University of Hawaii Press. p. 16. ISBN 0824822064. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

Alphabet: Some scholars consider the Manchu script to be a syllabic one.

- ↑ Gertraude Roth Li (2010). Manchu: A Textbook for Reading Documents (Second Edition) (2 ed.). Natl Foreign Lg Resource Ctr. p. 16. ISBN 0980045959. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

Alphabet: Some scholars consider the Manchu script to be a syllabic one. Others see it as having an alphabet with individual letters, some of which differ according to their position within a word. Thus, whereas Denis Sinor aruged in favor of a syllabic theory,30 Louis Ligeti preferred to consider the Manchu script and alphabetical one.31

() - ↑ Otgonbayar Chuluunbaatar (2008). Einführung in die Mongolischen Schriften (in German). Buske. ISBN 978-3-87548-500-4.

- 1 2 Biligsaikhan Batjargal; et al. (2011). "A Study of Traditional Mongolian Script Encodings and Rendering: Use of Unicode in OpenType fonts" (PDF). International Journal of Asian Language Processing. 21 (1): 23–43. Retrieved 2011-09-10.

- ↑ Version 5.00 of the Mongolian Baiti font may be displayed incorrectly in Windows Vista

- ↑ Bug 490534 - ZWJ and NNBSP rendered incorrectly in scripts like Mongolian

- ↑ Menk Qagan Tig, Menk Hawang Tig, Menk Garqag Tig, Menk Har_a Tig, and Menk Scnin Tig.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mongolian script. |

- Making Sense of the Traditional Mongolian Script

- StudyMongolian: Written forms with audio pronunciation

- Omniglot: Mongolian Alphabet

- The Silver Horde: Mongol Scripts

- Online tool for Mongolian script transliteration

- Automatic converter for Traditional Mongolian and Cyrillic Mongolian by the Computer College of Inner Mongolia University