Vasectomy

| Vasectomy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background | |

| Type | Sterilization |

| First use | 1899 (experiments from 1785)[1] |

| Failure rates (first year) | |

| Perfect use | 0.10%[2] |

| Typical use |

0.15%[2] "Vas-Clip" nearly 1% |

| Usage | |

| Duration effect | Permanent |

| Reversibility | Possible, but expensive. |

| User reminders | Two consecutive negative semen specimens required to verify no sperm. |

| Clinic review | All |

| Advantages and disadvantages | |

| STD protection | No |

| Benefits | No need for general anesthesia. Lower cost/less invasive than tubal ligation for women. |

| Risks | Temporary local inflammation or swelling of the testes. Long-term genital pain (PVPS). |

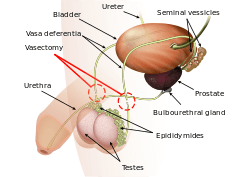

Vasectomy is a surgical procedure for male sterilization or permanent contraception. During the procedure, the male vas deferens are severed and then tied or sealed in a manner so as to prevent sperm from entering into the ejaculate and thereby prevent fertilization. Vasectomies are usually performed in a physician's office, medical clinic, or, when performed on an animal, in a veterinary clinic— hospitalization is not normally required as the procedure is not complicated, the incisions small, and the necessary equipment routine.

There are several methods by which a surgeon might complete a vasectomy procedure, all of which occlude (i.e. "seal") at least one side of each vas deferens. To help reduce anxiety and increase patient comfort, men who have an aversion to needles may consider a "no-needle" application of anesthesia while the "no-scalpel" or "open-ended" techniques help to accelerate recovery times and increase the chance of healthy recovery.

Due to the simplicity of the surgery, a vasectomy usually takes less than thirty minutes to complete. After a short recovery at the doctor's office (usually less than an hour), the patient is sent home to rest. Because the procedure is minimally invasive, many vasectomy patients find that they can resume their typical sexual behavior within a week, and do so with little or no discomfort.

Because the procedure is considered a permanent method of contraception and is not easily reversed, men are usually counseled/advised to consider how the long-term outcome of a vasectomy might affect them both emotionally and physically. The procedure is not often encouraged for young single men as their chances for biological parenthood are thereby more or less permanently reduced to almost zero by it. It is seldom performed on dogs (castration, a different procedure, remains the preferred reproductive control option for canines) but is regularly performed on bulls.[3]

Medical uses

A vasectomy is done to prevent fertility in males. It ensures that in most cases the person will be sterile after confirmation of success following surgery. The procedure is regarded as permanent because vasectomy reversal is costly and often does not restore the male's sperm count or sperm motility to prevasectomy levels. Men with vasectomies have a very small (nearly zero) chance of successfully impregnating a woman, but a vasectomy has no effect on rates of sexually transmitted infections.

After vasectomy, the testes remain in the scrotum where Leydig cells continue to produce testosterone and other male hormones that continue to be secreted into the blood-stream. Some studies have found that sexual desire after vasectomy may be somewhat diminished.[4][5]

When the vasectomy is complete, sperm cannot exit the body through the penis. Sperm are still produced by the testicles, but they are soon broken down and absorbed by the body. Much fluid content is absorbed by membranes in the epididymis, and much solid content is broken down by the responding macrophages and reabsorbed via the blood stream. Sperm is matured in the epididymis for about a month before leaving the testicles. After vasectomy, the membranes must increase in size to absorb and store more fluid; this triggering of the immune system causes more macrophages to be recruited to break down and reabsorb more solid content. Within one year after vasectomy, sixty to seventy per cent of vasectomized men develop antisperm antibodies.[6] In some cases, vasitis nodosa, a benign proliferation of the ductular epithelium, can also result.[7][8] The accumulation of sperm increases pressure in the vas deferens and epididymis. The entry of the sperm into the scrotum can cause sperm granulomas to be formed by the body to contain and absorb the sperm which the body will treat as a foreign biological substance (much like a virus or bacterium).[9]

Efficacy

Early failure rates, i.e. pregnancy within a few months after vasectomy, typically result from unprotected sexual intercourse too soon after the procedure while some sperm continue to pass through the vasa deferentia. Most physicians and surgeons who perform vasectomies recommend one (sometimes two) postprocedural semen specimens to verify a successful vasectomy; however, many men fail to return for verification tests citing inconvenience, embarrassment, forgetfulness, or certainty of sterility.[10] In January 2008, the F.D.A. cleared a home test called SpermCheck Vasectomy that allows patients to perform postvasectomy confirmation tests themselves;[11] however, compliance for postvasectomy semen analysis in general remains low.

Late failure, i.e. pregnancy following spontaneous recanalization of the vasa deferentia, has also been documented.[12] The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists states there is a generally agreed-upon rate of late failure of about one in 2000 vasectomies— vastly better than tubal ligations for which the failure rate is one in every 200 to 300 cases.[13] A 2005 review including both early failures and late failures described a total of 183 failures or recanalizations from approximately 43,642 vasectomies (0.4%), and sixty pregnancies after 92,184 vasectomies (0.07%).[14]

Complications

Short-term possible complications include infection, bruising and bleeding into the scrotum resulting in a collection of blood known as a hematoma. A study in 2012 demonstrated an infection rate of 2.5% postvasectomy.[15] The stitches on the small incisions required are prone to irritation, though this can be minimized by covering them with gauze or small adhesive bandages. The primary long-term complications are chronic pain conditions or syndromes that can affect any of the scrotal, pelvic or lower-abdominal regions, collectively known as post-vasectomy pain syndrome. Though vasectomy results in increases in circulating immune complexes, these increases are transient. Data based on bestial and human studies indicate these changes do not result in increased incidence of atherosclerosis. The risk of prostate and testicular cancer is not affected by vasectomy.[16][17] According to one study long-term postvasectomy discomfort is experienced at a frequency which ranges between 15% and 33% of vasectomy patients.[18]

Postvasectomy pain

Post-vasectomy pain syndrome (P.V.P.S.) is a chronic and sometimes debilitating condition that may develop immediately or several years after vasectomy.[19] One survey cites studies that estimate incidence at one case in every ten to thirty vasectomies.[20] The pain can be constant orchialgia or epididymal pain (epididymitis), or it can be pain that occurs only at particular times such as with sexual intercourse, ejaculation, or physical exertion.[9]

Psychological effects

Approximately 90% are generally reported in reviews as being satisfied with having had a vasectomy,[21] while between 7-10% of men regret their decision.[22] Regret was less common when both people in the relationship agreed on the procedure.[23]

Men who are of a younger age at the time of having a vasectomy are significantly more likely to regret and seek a reversal of their vasectomy, with one study showing men for example in their twenties being 12.5 times more likely to undergo a vasectomy reversal later in life (and including some who chose sterilization at a young age),[24] promoting a greater level of prevasectomy counseling as being required.

Dementia

An association between vasectomy and primary progressive aphasia, a rare variety of frontotemporal dementia, was reported.[23] However, it is unclear if there is a cause and effect relationship.[25] The putative mechanism is a cross-reactivity between brain and sperm, including the shared presence of neural surface antigens.[26] In addition, the cytoskeletal tau protein has been found only to exist outside of the CNS in the manchette of sperm.[26]

Procedure

The traditional incision approach of vasectomy involves numbing of the scrotum with local anesthetic (although some men's physiology may make access to the vas deferens more difficult in which case general anesthesia may be recommended) after which a scalpel is used to make two small incisions, one on each side of the scrotum at a location that allows the surgeon to bring each vas deferens to the surface for excision. The vasa deferentia are cut (sometimes a section may be removed altogether), separated, and then at least one side is sealed by ligating (suturing), cauterizing (electrocauterization), or clamping.[27] There are several variations to this method that improve healing, effectiveness, and which help mitigate long-term pain such as post-vasectomy pain syndrome (PVPS) or epididymitis.

- Fascial interposition: Recanalization of the vas deferens is a known cause of vasectomy failure(s).[28] Fascial interposition ("FI"), in which a tissue barrier is placed between the cut ends of the vas by suturing, may help to prevent this type of failure, increasing the overall success rate of vasectomy while leaving the testicular end within the confines of the fascia.[29] The fascia is a fibrous protective sheath that surrounds the vas deferens as well as all other body muscle tissue. This method, when combined with intraluminal cautery ( where one or both sides of the vas deferens are electrically "burned" closed to prevent recanalization), has been shown to increase the success rate of vasectomy procedures.

- No-needle anesthesia: Fear of needles for injection of local anesthesia is well known.[30] In 2005, a method of local anesthesia was introduced for vasectomy which allows the surgeon to apply it painlessly with a special jet-injection tool, as opposed to traditional needle application. The numbing agent is forced/pushed onto and deep enough into the scrotal tissue to allow for a virtually pain-free surgery. Initial surveys show a very high satisfaction rate amongst vasectomy patients.[30] Once the effects of no-needle anesthesia set in, the vasectomy procedure is performed in the routine manner.

- No-scalpel vasectomy (NSV): Also known as a "key-hole" vasectomy,[31] is a vasectomy in which a sharp hemostat (as opposed to a scalpel) is used to puncture the scrotum. This method has come into widespread use as the resulting smaller "incision" or puncture wound typically limits bleeding and hematomas. Also the smaller wound has less chance of infection, resulting in faster healing times compared to the larger/longer incisions made with a scalpel. The surgical wound created by the No-Scalpel method usually does not require stitches. NSV is the most commonly performed type of minimally invasive vasectomy, and both describe the method of vasectomy that leads to access of the vas deferens.[32]

- Open-ended vasectomy: In this procedure the testicular end of the vas deferens is not sealed, which allows continued streaming of sperm into the scrotum. This method may avoid testicular pain resulting from increased back-pressure in the epididymis.[9] Studies suggest that this method may reduce long-term complications such as post-vasectomy pain syndrome.[33][34]

- Vas irrigation: Injections of sterile water or euflavine (which kills sperm) are put into the distal portion of the vas at the time of surgery which then brings about a near-immediate sterile ("azoospermatic") condition. The use of euflavine does however, tend to decrease time (or, number of) ejaculations to azoospermia vs. the water irrigation by itself. This additional step in the vasectomy procedure, (and similarly, fascial interposition), has shown positive results but is not as prominently in use, and few surgeons offer it as part of their vasectomy procedure.[35]

Other techniques

The following vasectomy methods have purportedly had a better chance of later reversal but have seen less use by virtue of known higher failure rates (i.e., recanalization).An earlier clip device, the VasClip, is no longer on the market, due to unacceptably high failure rates.[36][37][38]

The VasClip method, though considered reversible, has had a higher cost and resulted in lower success rates. Also, because the vasa deferentia are not cut or tied with this method, it could technically be classified as other than a vasectomy. Vasectomy reversal (and the success thereof) was conjectured to be higher as it only required removing the Vas-Clip device. This method achieved limited use, and scant reversal data are available.[38]

Vas occlusion techniques

- Injected plugs: There are two types of injected plugs which can be used to block the vasa deferentia. Medical-grade polyurethane (M.P.U.) or medical-grade silicone rubber (M.S.R.) starts as a liquid polymer that is injected into the vas deferens after which the liquid is clamped in place until is solidifies (usually in a few minutes).[39]

- Intra-Vas device: The vasa deferentia can also be occluded by an Intra-Vas device or "I.V.D.". A small cut is made in the lower abdomen after which a soft silicone or urethane plug is inserted into each vas tube thereby blocking (occluding) sperm. This method allows for the vas to remain intact. I.V.D. technique is done in an out-patient setting with local anesthetic, similar to a traditional vasectomy. I.V.D. reversal can be performed under the same conditions making it much less costly than vasovasostomy which can require general anesthesia and longer surgery time.[40]

Both vas occlusion techniques require the same basic patient setup: local anesthesia, puncturing of the scrotal sac for access of the vas, and then plug or injected plug occlusion. The success of the aforementioned vas occlusion techniques is not clear and data are still limited. Studies have shown, however, that the time to achieve sterility is longer than the more prominent techniques mentioned in the beginning of this article. The satisfaction rate of patients undergoing I.V.D. techniques has a high rate of satisfaction with regard to the surgery experience itself.[35]

Recovery

Sexual intercourse can usually be resumed in about a week (depending on recovery); however, pregnancy is still possible as long as the sperm count is above zero. Another method of contraception must be relied upon until a sperm count is performed either two months after the vasectomy or after ten to twenty ejaculations have occurred.[41]

After a vasectomy, contraceptive precautions must be continued until azoospermia is confirmed. Usually two semen analyses at three and four months are necessary to confirm azoospermia. The British Andrological Society has recommended that a single semen analysis confirming azoospermia after sixteen weeks is sufficient.[42]

Conceiving after vasectomy

In order to allow the possibility of reproduction via artificial insemination after vasectomy, some men opt for cryopreservation of sperm before sterilization. It is advised that all men having a vasectomy consider freezing some sperm before the procedure. Dr Allan Pacey (senior lecturer in andrology at Sheffield University and secretary of the British Fertility Society) notes that men who he sees for a vasectomy reversal which has not worked, express wishing they knew they could have stored sperm. Pacey notes, "The problem is you're asking a man to foresee a future where he might not necessarily be with his current partner - and that may be quite hard to do when she's sitting next to you."[43]

The cost of Cryopreservation (Sperm Banking) itself may also be substantially less (approximately every five years) than alternative Vaso-vasectomy procedure(s), compared to the costs of In-vitro fertilization which usually run to US$15,000.

Intracytoplasmic sperm injection: Sperm can be aspirated from the testicles or the epididymis, and while there is not enough for successful artificial insemination, there is enough to fertilize an ovum by I.C.S.I. This avoids the problem of anti-sperm antibodies and may result in a faster pregnancy. IVF (In-vitro fertilization) may be less costly (see aforementioned text) per cycle than reversal in some health-care systems, but a single I.V.F. cycle is often insufficient for conception. Disadvantages include the need for procedures on the woman, and the standard potential side-effects of I.V.F. for both the mother and the child.[44]

Vasectomy reversal

Although men considering vasectomies should not think of them as reversible, and most men and their partners are satisfied with the operation,[45][46] life circumstances and outlooks can change, and there is a surgical procedure to reverse vasectomies using vasovasostomy (a form of microsurgery first performed by Earl Owen in 1971[47][48]). Vasovasostomy is effective at achieving pregnancy in a variable percentage of cases, and total out-of-pocket costs in the United States are often upwards of $10,000.[49] The typical success rate of pregnancy following a vasectomy reversal is around 55% if performed within 10 years, and drops to around 25% if performed after 10 years.[50] After reversal, sperm counts and motility are usually much lower than pre-vasectomy levels. There is evidence that men who have had a vasectomy may produce more abnormal sperm, which would explain why even a mechanically successful reversal does not always restore fertility.[51][52] The higher rates of aneuploidy and diploidy in the sperm cells of men who have undergone vasectomy reversal may lead to a higher rate of birth defects.[51]

Some reasons that men seek vasectomy reversals include wanting a family with a new partner following a relationship break-down/divorce, their original wife/partner dying and subsequently going on to repartner and to want children, the unexpected death of a child, or a long-standing couple changing their minds some time later often by situations such as improved finances or existing children approaching the age of school or leaving home.[43] Patients often comment that they never anticipated the possibility of a relationship break-down or death (of their partner or child), or how that may affect their situation at the time of having their vasectomy. A small number of vasectomy reversals are also performed in attempts to relieve postvasectomy pain syndrome.[53]

Prevalence

Vasectomy is the most effective permanent form of contraception available to men. In nearly every way that vasectomy can be compared to tubal ligation[54] it has a more positive outlook. Vasectomy is more cost effective, less invasive, has techniques that are emerging that may facilitate easier reversal, and has a much lower risk of postoperative complications. Despite this, in the United States, vasectomy is utilized at less than half the rate of the alternative female "tubal ligation".[55] According to the research, vasectomy is least utilized among black and Latin populations, the U.S. groups that have the highest rates of female sterilization.[55]

New Zealand, in contrast to the U.S., has higher levels of vasectomy than tubal ligation uptake. 18% of all men, and 25% of all married men have had a vasectomy. The age cohort with the highest level of vasectomy was 40-49 where 57% of men had taken it up.[56] Canada, the UK, Bhutan and the Netherlands all have similar levels of uptake.[57]

History

The first recorded vasectomy was performed on a dog in 1823.[58] A short time after that, R. Harrison of London performed the first human vasectomy; however the surgery was not done for sterilization purposes, but to bring about atrophy of the prostate. Soon, however, it was believed to have benefits for eugenics. The first case report of vasectomy in the U.S. was in 1897, by A. J. Ochsner, a surgeon in Chicago, in a paper titled, "Surgical treatment of habitual criminals." He believed vasectomy to be a simple, effective means for stemming the tide of racial degeneration widely believed to be occurring. In 1902, Harry C. Sharp, the surgeon at the Indiana Reformatory, reported that he had sterilized 42 inmates, in an effort to both reduce criminal behavior in those individuals and prevent the birth of future criminals.[59] Vasectomy began to be regarded as a method of birth control during the Second World War. The first vasectomy program on a national scale was launched in 1954 in India.[60]

Society and culture

Availability and legality

Vasectomy costs are (or may be) covered in different countries, as a method of both contraception or population control, with some offering it as a part of a national health insurance. The Affordable Care Act of the U.S. does not cover vasectomy. Vasectomy was generally considered illegal in France until 2001, due to provisions in the Napoleonic Code forbidding "self-mutilation". No French law specifically mentioned vasectomy until a 2001 law on contraception and foeticide permitted the procedure.[61]

Sharia (Islamic law) traditionally does not permit permanent sterilization.[62] However, on July 2, 2012, the Indonesian Ulema Council agreed to permit vasectomies in Indonesia subject to certain requirements, including:[63]

- The vasectomy is not intended to be permanent;

- The man is at least 50 years old;

- The man's wife granted permission;

- The procedure is not being carried out for "immoral purposes."

Ideological issues

The emphasis on "shared responsibility" has been taken up in recent research and articles by Terry and Braun, who regard much of the earlier psychological research on vasectomy as seemingly negative, or 'suspicious' in tone.[64] In research based on 16 New Zealand men (chosen for their enthusiasm on the topic of vasectomy), researchers extracted primary themes from their interviews of "taking responsibility" and "vasectomy as an act of minor heroism’.[65]

The need to "target men’s involvement in reproductive and contraceptive practices" was historically raised on a global scale at the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) in Cairo,[66] in relation to both population control and decreasing the levels of inequality in the ‘contraceptive burden’, which has traditionally placed responsibility for contraception unfairly upon women. Vigoya has referred to a global "cultura anticonceptiva femenina" - a female contraceptive culture, where, despite the possibility of men taking more responsibility for contraception, there is virtually nowhere in the world where true contraceptive equality exists.[67]

Feministic researchers emphasize the positive identities that men can take up post vasectomy, as a "man who takes on responsibility for the contraceptive task"[65] and a man who is willing to "sacrifice" his fertility for his partner and family's sake.[64] Often these sorts of accounts are constructed within the 'contraceptive economy' of a relationship, in which women have maintained responsibility of the contraceptive task up until the point of the operation. Terry notes that a man undergoing a vasectomy may also mean he receives a high degree of gratitude and positive reinforcement for making the choice to be sterilised, perhaps more so than a woman who has been on an oral contraceptive or similar for years prior.[65]

Vasectomies are condemned by the Roman Catholic Church.[68]

Tourism

Medical tourism, where a patient travels to a less developed location where a procedure is cheaper to save money and combine convalescence with a vacation, is infrequently used for vasectomy due to its low cost, but is more likely to be used for vasectomy reversal. Many overseas hospitals list vasectomy as one of their qualified surgical procedures. Medical tourism has come under the scrutiny of some governments for quality of care and postoperative care issues.[69]

See also

- Male contraceptive

- Sperm granuloma

- Testicular sperm extraction

- Orchiectomy

- List of surgeries by type

References

- ↑ Popenoe P (1934). "The progress of eugenic sterilization". Journal of Heredity. 25 (1): 19.

- 1 2 Trussell, James (2011). "Contraceptive efficacy". In Hatcher, Robert A.; Trussell, James; Nelson, Anita L.; Cates, Willard Jr.; Kowal, Deborah; Policar, Michael S. (eds.). Contraceptive technology (20th revised ed.). New York: Ardent Media. pp. 779–863. ISBN 978-1-59708-004-0. ISSN 0091-9721. OCLC 781956734. Table 26–1 = Table 3–2 Percentage of women experiencing an unintended pregnancy during the first year of typical use and the first year of perfect use of contraception, and the percentage continuing use at the end of the first year. United States.

- ↑ Dean A. Hendrickson; A. N. Baird (5 June 2013). Turner and McIlwraith's Techniques in Large Animal Surgery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 541. ISBN 978-1-118-68404-7.

- ↑ Nielsen CM, Genster HG (1980). "Male sterilization with vasectomy. The effect of the operation on sex life". Ugeskrift for Lægerer. 142 (10): 641–643. PMID 7368333.

- ↑ Dias, P. L. R. (1983). "The long-term effects of vasectomy on sexual behaviour". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 67 (5): 333–338. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb00350.x. PMID 6869041.

- ↑ Hattikudur, S.; Shanta, S. RAO; Shahani, S.K.; Shastri, P.R.; Thakker, P.V.; Bordekar, A.D. (2009). "Immunological and Clinical Consequences of Vasectomy*". Andrologia. 14 (1): 15–22. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0272.1982.tb03089.x. PMID 7039414.

- ↑ Deshpande RB, Deshpande J, Mali BN, Kinare SG (1985). "Vasitis nodosa (a report of 7 cases)". J Postgrad Med. 31 (2): 105–8. PMID 4057111.

- ↑ Hirschowitz, L; Rode, J; Guillebaud, J; Bounds, W; Moss, E (1988). "Vasitis nodosa and associated clinical findings". Journal of Clinical Pathology. 41 (4): 419–423. doi:10.1136/jcp.41.4.419. PMC 1141468

. PMID 3366928.

. PMID 3366928. - 1 2 3 Christiansen C, Sandlow J (2003). "Testicular Pain Following Vasectomy: A Review of Post vasectomy Pain Syndrome". Journal of Andrology. 24 (3): 293–8. PMID 12721203.

- ↑ Christensen, R. E.; Maples, D. C. (2005). "Postvasectomy Semen Analysis: Are Men Following Up?". The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 18: 44–47. doi:10.3122/jabfm.18.1.44.

- ↑ Klotz, Kenneth L.; Coppola, Michael A.; Labrecque, Michel; Brugh Vm, Victor M.; Ramsey, Kim; Kim, Kyung-ah; Conaway, Mark R.; Howards, Stuart S.; Flickinger, Charles J.; Herr, John C. (2008). "Clinical and Consumer Trial Performance of a Sensitive Immunodiagnostic Home Test That Qualitatively Detects Low Concentrations of Sperm Following Vasectomy". The Journal of Urology. 180 (6): 2569–2576. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2008.08.045. PMC 2657845

. PMID 18930494.

. PMID 18930494. - ↑ Philp, T; Guillebaud, J; Budd, D (1984). "Late failure of vasectomy after two documented analyses showing azoospermic semen". BMJ. 289 (6437): 77–79. doi:10.1136/bmj.289.6437.77. PMC 1441962

. PMID 6428685.

. PMID 6428685. - ↑ Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. "Sterilisation for women and men: what you need to know".

- ↑ Griffin, T; Tooher, R; Nowakowski, K; Lloyd, M; Maddern, G (2005). "HOW LITTLE IS ENOUGH? THE EVIDENCE FOR POST-VASECTOMY TESTING". The Journal of Urology. 174 (1): 29–36. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000161595.82642.fc. PMID 15947571.

- ↑ Nevill et al (2013) Surveillance of surgical site infection post vasectomy. Journal of Infection Prevention. January 2013. Vol 14(1) http://bji.sagepub.com/content/14/1/14.abstract

- ↑ Schwingl, Pamela J; Guess, Harry A (2000). "Safety and effectiveness of vasectomy". Fertility and Sterility. 73 (5): 923–936. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(00)00482-9. PMID 10785217.

- ↑ "AUA Responds to Study Linking Vasectomy with Prostate Cancer". American Urological Association. Retrieved 2016-03-19.

- ↑ McMahon AJ, Buckley J, Taylor A, Lloyd SN, Deane RF, Kirk D (February 1992). "Chronic testicular pain following vasectomy" (PDF). Br J Urol. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 69 (2): 188–91. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.1992.tb15494.x. PMID 1537032.

- ↑ Nangia, Ajay K.; Myles, Jonathan L.; Thomas Aj, Anthony J. (2000). "VASECTOMY REVERSAL FOR THE POST-VASECTOMY PAIN SYNDROME: : A CLINICAL AND HISTOLOGICAL EVALUATION". The Journal of Urology. 164 (6): 1939–1942. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(05)66923-6. PMID 11061886.

- ↑ Potts, Jeannette M. (2008). "Genitourinary Pain And Inflammation". Current Clinical Urology: 201–209. doi:10.1007/978-1-60327-126-4_13. ISBN 978-1-58829-816-4.

|chapter=ignored (help) - ↑ THONNEAU, P.; D'ISLE, BÉATRICE (1990). "Does vasectomy have long-term effects on somatic and psychological health status?". International Journal of Andrology. 13 (6): 419–432. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2605.1990.tb01050.x. PMID 2096110.

- ↑ Labrecque, Michel; Paunescu, Cristina; Plesu, Ioana; Stacey, Dawn; Légaré, France (2010). "Evaluation of the effect of a patient decision aid about vasectomy on the decision-making process: a randomized trial". Contraception. 82 (6): 556–562. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2010.05.003. PMID 21074020.

- 1 2 Köhler TS, Fazili AA, Brannigan RE (August 2009). "Putative health risks associated with vasectomy". Urol. Clin. North Am. 36 (3): 337–45. doi:10.1016/j.ucl.2009.05.004. PMID 19643236.

- ↑ POTTS, J.M.; PASQUALOTTO, F.F.; NELSON, D.; THOMAS, A.J.; AGARWAL, A. (June 1999). "PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS ASSOCIATED WITH VASECTOMY REVERSAL" (PDF). The Journal of Urology. 161 (6): 1835–1839. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(05)68819-2. PMID 10332448.

- ↑ Köhler, TS.; Choy, JT.; Fazili, AA.; Koenig, JF.; Brannigan, RE. (Nov 2012). "A critical analysis of the reported association between vasectomy and frontotemporal dementia". Asian J Androl. 14 (6): 903–4. doi:10.1038/aja.2012.94. PMC 3720109

. PMID 23064682.

. PMID 23064682. - 1 2 Rogalski E, Weintraub S, Mesulam MM (2013). "Are there susceptibility factors for primary progressive aphasia?". Brain Lang. 127 (2): 135–8. doi:10.1016/j.bandl.2013.02.004. PMC 3740011

. PMID 23489582.

. PMID 23489582. - ↑ Cook, Lynley A.; Pun, Asha; Gallo, Maria F; Lopez, Laureen M; Van Vliet, Huib AAM (2007). Cook, Lynley A., ed. "Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews": CD004112. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004112.pub3. PMID 17443540.

|chapter=ignored (help) - ↑ webmaster@vasectomy-information.com (2007-09-14). "Recanalization of the vas deferens". Vasectomy-information.com. Retrieved 2011-12-28.

- ↑ Sokal, David; Irsula, Belinda; Hays, Melissa; Chen-Mok, Mario; Barone, Mark A; Investigator Study, Group (2004). "Vasectomy by ligation and excision, with or without fascial interposition: a randomized controlled trial ISRCTN77781689". BMC Medicine. 2 (1): 6. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-2-6. PMC 406425

. PMID 15056388.

. PMID 15056388.

- 1 2 Weiss, RS; Li, PS (2005). "No-needle jet anesthetic technique for no-scalpel vasectomy". The Journal of Urology. 173 (5): 1677–80. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000154698.03817.d4. PMID 15821547.

- ↑ Cook, Lynley A.; Pun, Asha; Gallo, Maria F; Lopez, Laureen M; Van Vliet, Huib AAM (2007). Cook, Lynley A., ed. "Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews": CD004112. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004112.pub3. PMID 17443540.

|chapter=ignored (help) - ↑ Panel Members: Ira D. Sharlip, M.D., Panel Co-Chair Clinical Professor Department of Urology University of California, San Francisco, CA San Francisco, CA Arnold M. Belker, M.D., Panel Co-Chair Emeritus Clinical Professor Department of Urology University of Louisville School of Medicine Louisville, Kentucky Stanton Honig, M.D. Professor of Surgery/Urology University of Connecticut Farmington CT The Urology Center New Haven, CT Michel Labrecque, M.D., Ph.D. Professor Department of Family and Emergency Medicine Université Laval Quebec City, Canada Joel L. Marmar, M.D. Professor of Urology Cooper Medical School of Rowan University Camden, NJ Lawrence S. Ross, M.D. Clarence C. Saelhof Professor Emeritus Department of Urology University of Illinois at Chicago Chicago, IL Jay I. Sandlow, M.D. Professor of Urology Medical College of Wisconsin Milwaukee, WI David C. Sokal, MD Senior Scientist Clinical Sciences Department FHI 360 Durham, NC (2015). "American Urology Association Vasectomy guideline 2012 (amended 2015)" (PDF). American Urology Association. https://www.auanet.org. Retrieved 2015. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help); External link in|publisher=(help) - ↑ Moss, WM (December 1992). "A comparison of open-end versus closed-end vasectomies: a report on 6220 cases". Contraception. 46 (6): 521–5. doi:10.1016/0010-7824(92)90116-B. PMID 1493712.

- ↑ Shapiro, EI; Silber, SJ (November 1979). "Open-ended vasectomy, sperm granuloma, and postvasectomy orchialgia". Fertility and Sterility. 32 (5): 546–50. PMID 499585.

- 1 2 Cook, Lynley A.; Van Vliet, Huib AAM; Lopez, Laureen M; Pun, Asha; Gallo, Maria F (2007). Cook, Lynley A., ed. "Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews". doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003991.pub3.

|chapter=ignored (help) - ↑ Levine, LA; Abern, MR; Lux, MM (2006). "Persistent motile sperm after ligation band vasectomy". The Journal of Urology. 176 (5): 2146–8. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2006.07.028. PMID 17070280.

- ↑ "Male Contraception Update for the public - August 2008, 3(8)". Imccoalition.org. Retrieved 2011-12-28.

- 1 2 http://www.vasweb.com/vasclip.htm[]

- ↑ "Injected plugs". MaleContraceptives.org. 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2011-12-28.

- ↑ "Intra Vas Device (IVD)". MaleContraceptives.org. Retrieved 2011-12-28.

- ↑ Healthwise Staff (May 13, 2010). "Vasectomy Procedure, Effects, Risks, Effectiveness, and More". webmd.com. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- ↑ "Post Vasectomy Semen Analysis". Cambridge IVF. Cambridge IVF. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- 1 2 Murphy, Clare. "Divorce fuels vasectomy reversals", BBC News, 18 March 2009. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- ↑ Shridharani, Anand; Sandlow, Jay I (2010). "Vasectomy reversal versus IVF with sperm retrieval: which is better?". Current Opinion in Urology. 20 (6): 503–509. doi:10.1097/MOU.0b013e32833f1b35. PMID 20852426.

- ↑ Landry E, Ward V (1997). "Perspectives from Couples on the Vasectomy Decision: A Six-Country Study" (PDF). Reproductive Health Matters. (special issue): 58–67.

- ↑ Jamieson, D (2002). "A comparison of women's regret after vasectomy versus tubal sterilization". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 99 (6): 1073–1079. doi:10.1016/S0029-7844(02)01981-6.

- ↑ "About Vasectomy Reversal". Professor Earl Owen's homepage. Retrieved 2007-11-29.

- ↑ Owen ER (1977). "Microsurgical vasovasostomy: a reliable vasectomy reversal". Urology. 167 (2 Pt 2): 1205. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(02)80388-3. PMID 11905902.

- ↑ Vasectomy Reversal http://www.epigee.org/guide/vasectomy_reversal.html

- ↑ Cited in Laurance, Jeremy (2009) "Vasectomy Reversal: First Cut Isn't Final" in The Independent 30 March 2009 http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/health-and-families/health-news/vasectomy-reversal-first-cut-isnt-final-1657039.html

- 1 2 Sukcharoen, Nares; Ngeamvijawat, J; Sithipravej, T; Promviengchai, S (2003). "High sex chromosome aneuploidy and diploidy rate of epididymal spermatozoa in obstructive azoospermic men". Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics. 20 (5): 196–203. doi:10.1023/A:1023674110940. PMC 3455301

. PMID 12812463.

. PMID 12812463. - ↑ Abdelmassih, V.; Balmaceda, JP; Tesarik, J; Abdelmassih, R; Nagy, ZP (2002). "Relationship between time period after vasectomy and the reproductive capacity of sperm obtained by epididymal aspiration". Human Reproduction. 17 (3): 736–740. doi:10.1093/humrep/17.3.736. PMID 11870128.

- ↑ Horovitz, D. (February 2012). "Vasectomy reversal provides long-term pain relief for men with the post-vasectomy pain syndrome.". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine. 187: 613–7. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2011.10.023. PMID 22177173.

- ↑ Kim, Edward. "Vasectomy Versus Other Types of Contraception".

- 1 2 Shih G, Turok DK, Parker WJ (April 2011). "Vasectomy: the other (better) form of sterilization". Contraception. 83 (4): 310–5. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2010.08.019. PMID 21397087.

- ↑ Sneyd, Mary Jane; Cox, Brian; Paul, Charlotte; Skegg, David C.G. (2001). "High prevalence of vasectomy in New Zealand". Contraception. 64 (3): 155–159. doi:10.1016/S0010-7824(01)00242-6.

- ↑ Pile, John M.; Barone, Mark A. (2009). "Demographics of Vasectomy—USA and International". Urologic Clinics of North America. 36 (3): 295–305. doi:10.1016/j.ucl.2009.05.006. PMID 19643232.

- ↑ Leavesley, JH (1980). "Brief history of vasectomy". Family planning information service. 1 (5): 2–3. PMID 12336890.

- ↑ Reilly, Phillip (1991). The Surgical Solution: A History of Involuntary Sterilization in the United States. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 30–33.

- ↑ Sharma, Sanjay (April–June 2014). "A Study of Male Sterilization with No Scalpel Vasectomy" (PDF). JK Science. 16 (2): 67. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ↑ Latham, Melanie (2002-07-05). Regulating reproduction: a century of conflict in Britain and France. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-5699-3.

- ↑ "Sub-Index for: Medical Issues". Islam Today. Islam Today. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ↑ "Vasectomies are now allowed, MUI". The Jakarta Post. July 4, 2012.

- 1 2 Terry, Gareth; Braun, Virginia (2011). "'I'm committed to her and the family': positive accounts of vasectomy among New Zealand men". Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 29 (3): 276–291. doi:10.1080/02646838.2011.592976.

- 1 2 3 Terry, G.; Braun, V. (2011). "'It's kind of me taking responsibility for these things': Men, vasectomy and 'contraceptive economies'" (PDF). Feminism & Psychology. 21 (4): 477–495. doi:10.1177/0959353511419814.

- ↑ Mundigo A (2000) Re-conceptualizing the role of men in the post-Cairo era" Culture, Health & Sexuality 2(3) 323–337; cited in Terry, G and Braun, V (2011). 'It’s kind of me taking responsibility for these things': men, vasectomy and 'contraceptive economies'. Feminism & Psychology, 21(4), pp. 477–495. Available online at:http://oro.open.ac.uk/34285/1/It%27s%20kind%20of%20me%20taking%20responsbility%20for%20these%20things.pdf

- ↑ cited in Terry, G and Braun, V (2011). 'It’s kind of me taking responsibility for these things': men, vasectomy and 'contraceptive economies'. Feminism & Psychology, 21(4), p.1 Available online at: http://oro.open.ac.uk/34285/1/It%27s%20kind%20of%20me%20taking%20responsbility%20for%20these%20things.pdf

- ↑ http://www.catholic.com/quickquestions/can-a-catholic-husband-who-has-had-a-vasectomy-receive-communion

- ↑ Lunt, Neil; Carrera, Percivil (2010). "Medical tourism: Assessing the evidence on treatment abroad". Maturitas. 66 (1): 27–32. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.01.017. PMID 20185254.

External links

- Vasectomy : Procedure

- MedlinePlus Encyclopedia

- How to treat: vasectomy and reversal, Australian Doctor, 2 July 2014