Vindolanda tablets

|

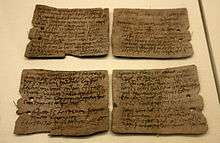

Tablet 343: Letter from Octavius to Candidus concerning supplies of wheat, hides and sinews. | |

| Material | Wood |

|---|---|

| Size | Length: 182 mm (7.2 in) |

| Writing | Latin |

| Created | 1stC (late)–2ndC (early) |

| Period/culture | Romano-British |

| Place | Vindolanda |

| Present location | Room 49, British Museum, London |

| Registration | 1989,0602.74 |

The Vindolanda tablets are the oldest surviving handwritten documents in Britain. They are also probably the best source of information about life on the northern frontier of Roman Britain.[1][2][3] Written on fragments of thin, post-card sized wooden leaf-tablets with carbon-based ink, the tablets date to the 1st and 2nd centuries AD (roughly contemporary with Hadrian's Wall). Although similar records on papyrus were known from elsewhere in the Roman Empire, wooden tablets with ink text had not been recovered until 1973, when archaeologist Robin Birley discovered these artefacts at the site of a Roman fort in Vindolanda, northern England.[1][4]

The documents record official military matters as well as personal messages to and from members of the garrison of Vindolanda, their families, and their slaves. Highlights of the tablets include an invitation to a birthday party held in about 100 AD, which is perhaps the oldest surviving document written in Latin by a woman. Held at the British Museum, the texts of 752 tablets have been transcribed, translated and published as of 2010.[5] Tablets continue to be found at Vindolanda.

Description

The wood tablets found at Vindolanda were the first known surviving examples of the use of ink letters in the Roman period. The use of ink tablets was documented in contemporary records and Herodian in the third century AD wrote "a writing-tablet of the kind that were made from lime-wood, cut into thin sheets and folded face-to-face by being bent".[6][7]

The Vindolanda tablets are made from birch, alder and oak that grew locally, in contrast to stylus tablets, another type of writing tablet used in Roman Britain, which were imported and made from non-native wood. The tablets are 0.25–3 mm thick with a typical size being 20 cm × 8 cm (7.9 in × 3.1 in) (the size of a modern postcard). They were scored down the middle and folded to form diptychs with ink writing on the inner faces, the ink being carbon, gum arabic and water. Nearly 500 tablets were excavated in the 1970s and 1980s.[6]

First discovered in March 1973, the tablets were initially thought to be wood shavings until one of the excavators found two stuck together and peeled them apart to discover writing on the inside. They were taken to the epigraphist Richard Wright, but rapid oxygenation of the wood meant that they were black and unreadable by the time he was able to view them. They were sent to Alison Rutherford at Newcastle University Medical School for multi-spectrum photography, which led to infra-red photographs showing the scripts for researchers for the first time. The results were initially disappointing as the scripts were undecipherable. However, Alan Bowman at Manchester University and David Thomas at Durham University analysed the previously unknown form of cursive script and were able to produce transcriptions.[8]

Chronology

Vindolanda fort was garrisoned before the construction of Hadrian's Wall and most of the tablets are slightly older than the Wall, which was begun in 122 AD. The original director of excavations Robin Birley identified five periods of occupation and expansion:[9]

- c. AD 85–92, first fort constructed.

- c. AD 92–97, fort enlargement.

- c. AD 97–103, further fort enlargements.

- c. AD 104–120, hiatus and re-occupation.

- c. AD 120–130, the period when Hadrian's Wall was constructed

The tablets were produced in periods 2 and 3 (c. AD 92–103), with the majority written before AD 102.[10] They were used for official notes about the Vindolanda camp business and personal affairs of the officers and households. The largest group is correspondence of Flavius Cerialis, prefect of the ninth cohort of Batavians and that of his wife, Sulpicia Lepidina. Some correspondence may relate to civilian traders and contractors; for example Octavian, the writer of Tablet 343, is an entrepreneur dealing in wheat, hides and sinews, but this does not prove him to be a civilian.

Selected highlights

The best-known document is perhaps Tablet 291, written around AD 100 from Claudia Severa,[11] the wife of the commander of a nearby fort, to Sulpicia Lepidina, inviting her to a birthday party. The invitation is one of the earliest known examples of writing in Latin by a woman.[12] There are two handwriting styles in the tablet, with the majority of the text written in a professional hand (thought to be the household scribe) and with closing greetings personally added by Claudia Severa herself (on the lower right hand side of the tablet).[11][13]

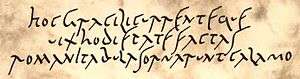

The tablets are written in Roman cursive script and throw light on the extent of literacy in Roman Britain. One of the tablets confirms that Roman soldiers wore underpants (subligaria),[14][15] and also testifies to a high degree of literacy in the Roman army.

There are only scant references to the indigenous Britons. Until the discovery of the tablets, historians could only speculate on whether the Romans had a nickname for the Britons. Brittunculi (diminutive of Britto; hence 'little Britons'), found on one of the Vindolanda tablets, is now known to be a derogatory, or patronising, term used by the Roman garrisons that were based in Northern Britain to describe the locals.[16]

Transcription

The tablets are written in forms of Roman cursive script, considered to be the forerunner of joined-up writing, which varies in style by author.[17] With few exceptions, they have been classified as Old Roman Cursive.[18]

The writing from Vindolanda appears as if it were written in a different alphabet to the Latin capitals used for inscriptions from other periods. The script is derived from the capital writing of the late first century BC and the first century AD. The text rarely shows the unusual or distorted letter-forms or the extravagant ligatures to be found in Greek papyri of the same period.[18] Additional challenges for transcription are the use of abbreviations such as "h" for homines (men) or "cos" for consularis (consular), and the arbitrary division of words at the end of lines for space reasons such as epistulas (letters) being split between the "e" and the rest of the word.[19]

The ink is often badly faded or survives as little more than a blur, so that in some instances transcription is not possible. In most cases the infra-red photographs provide a far more legible version of what was written than the original tablets. However, the photographs contain marks which appear similar to writing, but which certainly are not letters; additionally, they contain a great many lines, dots and other dark marks which may or may not be writing. Consequently, the published transcriptions have often had to be interpreted subjectively in deciding which marks should be regarded as writing.[18]

Contents

The Vindolanda tablets contain various letters of correspondence. For instance, the cavalry decurion Masculus wrote a letter to prefect Flavius Cerialis inquiring about the exact instructions for his men for the following day, including a polite request for more beer to be sent to the garrison (which had entirely consumed its previous stock of beer).[20] The documents also provide information about various roles performed by the men at the fort, such as a keeper of the bath-house, shoe-makers, construction workers, medical doctors, maintainers of wagons and kilns, and those put on plastering duty.[20]

Comparison to other sites

Wooden tablets have been found at twenty Roman settlements in Britain.[21] However, most of these sites did not yield the type of tablet found at Vindolanda, but rather "stylus tablets", marked with pointed metal styli. A significant number of ink tablets have been identified at Carlisle (also on Hadrian's Wall)[22]

The fact that letters were sent to and from places on Hadrian's Wall and further afield (Catterick, York, and London)[10] raises the question of why more letters have been found at Vindolanda than other sites, but it is not possible to give a definitive answer. The anaerobic conditions found at Vindolanda are not unique and identical deposits have been found in parts of London.[23] One possibility, given the fragile condition of the tablets found at Vindolanda, is that archaeologists excavating other Roman sites have overlooked evidence of writing in ink.

Imaging

The tablets were photographed using infra-red sensitive cameras in 1973 by Susan M. Blackshaw in the British Museum and more comprehensively in 1990 at Vindolanda by Alison Rutherford.[4][24] The tablets were scanned again using improved techniques in 2000–2001 with a Kodak Wratten 87C infra-red filter. The photographs are taken in infra-red to enhance the faded ink against the wood of the tablets, or between ink and dirt, to make the writing more visible.[25]

In 2002 the tablet images were used as part of a research programme to extend the use of the GRAVA iterative computer vision system[26] to aid the transcription of the Vindolanda tablets through a series of processes modelled on the best practice of papyrologists and to provide the images in an XML marked up format identifying the likely placement of characters and words with their transcription.[27]

In 2010 there was a collaboration between Centre for the Study of Ancient Documents at University of Oxford, the British Museum and the Archaeological Computing Research Group at University of Southampton using Polynomial texture mapping for detailed recording and edge detection.[28]

Online catalogue

The images, at a resolution suitable for web page display, and text of the tablets from Tab.Vindol. II [29] were published on-line.[n 1] Tablets from both Tab.Vindol. II [29] and Tab.Vindol. III [30] were published in a new online catalogue in 2010.[n 2]

Exhibition and impact

The tablets are held at the British Museum, where a selection of them is on display in its Roman Britain gallery (Room 49). The tablets featured in the list of British archaeological finds selected by experts at the British Museum for the 2003 BBC Television documentary Our Top Ten Treasures. Viewers were invited to vote for their favourite, and the tablets came top of the poll.

The Vindolanda Museum, run by the Vindolanda Trust, has funding so that a selection of tablets on loan from the British Museum can be displayed at the site where they were found.[31][32] The Vindolanda Museum put nine of the tablets on display in 2011. This loan of items to a regional museum is in line with British Museum's current policy of encouraging loans both internationally and nationally (as part of its Partnership UK scheme).[33]

Notes

- ↑ See Vindolanda Tablets Online. The digitization and on-line database project was a collaboration between the Centre for the Study of Ancient Documents and the Academic Computing Development Team at the University of Oxford with the support of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the Arts and Humanities Research Board. The project directors were Alan Bowman, Charles Crowther and John Pearce. See http://vindolanda.csad.ox.ac.uk/about.shtml

- ↑ See Vindolanda Tablets Online II. The Vindolanda Tablets were encoded with EpiDoc TEI (Text Encoding Initiative) for Centre for the Study of Ancient Documents at the University of Oxford as a part of the eSAD (e-Science and Ancient Documents) project. See

See also

References

- 1 2 "Our Top Ten British Treasures: The Vindolanda tablets". British Museum. 24 January 2011. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- ↑ Philip Howard (10 April 1974). "Lime-wood records of Agricola's soldiers". The Times. p. 20.

But the most significant discovery was a room littered with writing tablets. Of these eight or nine were the conventional stylus tablets, once covered with wax which was inscribed with a stylus. The rest are unique: very thin slivers of lime wood with writing on them in a carbon-based ink that can be deciphered by infrared photography. They are the first literary evidence from this period of British history, the equivalent of the records of the Roman Army found on papyrus in Egypt and Syria.

- ↑ Bowman 2003, p. 12.

- 1 2 Susan M. Blackshaw (Nov 1974), "The Conservation of the Wooden Writing-Tablets from Vindolanda Roman Fort, Northumberland", Studies in Conservation, International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, 19, No. 4: 244–246, JSTOR 1505731

- ↑ Bowman, A.K.; Thomas, J.D.; Tomlin, R.S.O. (2010), "The Vindolanda Writing-Tablets (Tabulae Vindolandenses IV, Part 1)", Britannia, Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies, 41: 187–224, doi:10.1017/S0068113X10000176

- 1 2 Bowman 1994a, pp. 15–16

- ↑ "Vindolanda tablets online; Writing tablets – forms and technology". Centre for the Study of Ancient Documents. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ↑ Birley 2005, pp. 57–58

- ↑ Bowman 1994a, p. 13

- 1 2 Franklin, Simon (2002), Writing, society and culture in early Rus, c. 950–1300, Cambridge University Press, pp. 42–45, ISBN 978-0-521-81381-5

- 1 2 Birley 2005, p. 85

- ↑ "Tab. Vindol. II 291; Wood writing tablet with a party invitation written in ink, in two hands, from Claudia Severa to Lepidina.". British Museum. 24 January 2011. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- Mount, Harry (21 July 2008). "Hadrian's soldiers writing home". The Daily Telegraph (telegraph.co.uk). Retrieved 23 February 2011.

The real prize of the Vindolanda tablets, though, are the earliest surviving letters in a woman's hand written in this country. In one letter, Claudia Severa wrote to her sister, Sulpicia Lepidina, the wife of a Vindolanda bigwig – Flavius Cerialis, prefect of the Ninth Cohort of Batavians: 'Oh how much I want you at my birthday party. You'll make the day so much more fun. I do so hope you can make it. Goodbye, sister, my dearest soul.'

- "Vindolanda Tablets Online". Tab. Vindol. II 291: Oxford University. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- Mount, Harry (21 July 2008). "Hadrian's soldiers writing home". The Daily Telegraph (telegraph.co.uk). Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ↑ Bowman and David Thomas, Alan (1994). "Tablet 291 - Translation and Notes". Vindolanda Tablets Online - based on Volume II of the Vindolanda writing tablets, published by Alan Bowman and David Thomas in 1994. Online material from book published by British Museum Press.

- ↑ "Vindolanda Tablets Online". Tab. Vindol. II 346: Oxford University. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

... I have sent (?) you ... pairs of socks from Sattua, two pairs of sandals and two pairs of underpants, two pairs of sandals ... Greet ...ndes, Elpis, Iu..., ...enus, Tetricus and all your messmates with whom I pray that you live in the greatest good fortune.

- ↑ Sebesta, Judith Lynn; Bonfante, Larissa (2001), The world of Roman costume, Univ of Wisconsin Press, p. 233, ISBN 978-0-299-13854-7

- ↑ "Vindolanda Tablets Online". Tab. Vindol. II 164: Oxford University. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

Especially noteworthy in the Vindolanda text is the occurrence, for the first time, of the patronising diminutive Brittunculi (line 5, contrast Brittones in line 1). This remains the only published text from Vindolanda which refers explicitly to the native Britons collectively or individually.

- ↑ Birley 2005, p. 64

- 1 2 3 Bowman, Alan K.; Thomas, John David (1984), Vindolanda: the Latin writing-tablets, A. Sutton, ISBN 978-0-86299-118-0

- ↑ Birley 2005, p. 65

- 1 2 Mike Ibeji (16 November 2012). "http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/romans/vindolanda_01.shtml Vindolanda]." BBC History. BBC.co.uk. Accessed 6 October 2016.

- ↑ "A Progress Report", Website of A Corpus of Writing-Tablets from Roman Britain, a research project of the Centre for the Study of Ancient Documents, Oxford, initiated around 2000. Retrieved 25 February 2011

- ↑ Tullie House Museum and Art Gallery in Carlisle has a small display of tablets.

- ↑ Birley 2005, p. 108

- ↑ Birley 2002, p. 29

- ↑ Bowman, Alan K; Brady, Michael; Academy, British; Royal Society (Great Britain) (2005), Images and artefacts of the ancient world, British Academy occasional paper, 4., Oxford, pp. 7–14, ISBN 978-0-19-726296-2

- ↑ Ground Reflective Adaptive Vision Architecture, see http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1763187

- ↑ Terras, Melissa M.; Robertson, Paul (2006), Image to interpretation: an intelligent system to aid historians in reading the Vindolanda texts, Oxford University Press, pp. 123–170, ISBN 978-0-19-920455-7

- ↑ Earl, Graeme (et al.) (2010). "Archaeological applications of polynomial texture mapping: analysis, conservation and representation". Journal of Archaeological Science. Elsevier. 37: 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2010.03.009. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- 1 2 Bowman 1994b.

- ↑ Bowman 2003.

- ↑ Knowles, Bija (10 June 2009). "Tablets to Return to Vindolanda in Spring 2011 Thanks to £4 Million Heritage Lottery Funding". Heritage Key. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- ↑ Henderson, Tony (29 September 2009). "Cash Boost Paves Way For Vindolanda Letters To Return Home". The Journal (Newcastle). p. 9.

It is more than 20 years since any of the Vindolanda tablets have been on show at the fort near Bardon Mill. But that is set to change after an award of £4m today from the Heritage Lottery Fund. That means a £6.5m project to upgrade both Vindolanda and its twin Roman Army Museum seven miles away at Carvoran will now go ahead... It is hoped that from spring 2011 the first batch of letters will return from the British Museum on a three to five-year loan, which can then be refreshed. "To have the letters back on public display would be wonderful and we are very excited," said Patricia Birley, director of the Vindolanda Trust. "Negotiations with the British Museum have been excellent and they are fully supportive of our efforts to get tablets back to Vindolanda."

- ↑ "Partnership UK". British Museum. 21 February 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

Sources

- Birley, Anthony (2002). Garrison Life at Vindolanda. Stroud. ISBN 978-0-7524-1950-3.

- Birley, Robin (2005). Vindolanda: extraordinary records of daily life on the northern frontier. Roman Army Museum Publications. ISBN 978-1-873136-97-3.

- Bowman, Alan K; Thomas, J David (1974). The Vindolanda writing tablets. Northern history booklet, no. 47. Graham. ISBN 978-0-85983-096-6.

- Bowman, Alan K; Thomas, J David (1983). Vindolanda: The Latin Writing Tablets. Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies. ISBN 978-0-90776-402-1.

- Bowman, Alan K (1994a). Life and letters on the Roman frontier : Vindolanda and its people. British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-1389-0.

- Bowman, Alan K; Thomas, J David (1994b). The Vindolanda writing-tablets : (Tabulae Vindolandenses II). British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-2300-4.

- Bowman, Alan K; Thomas, J David (2003). The Vindolanda writing-tablets (Tabulae Vindolandenses III). British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-2249-6.

- Bowman, Alan K; Thomas, J David; Tomlin, R. S. O. (2010). The Vindolanda Writing- Tablets (Tabulae Vindolandenses IV, Part 1). Britannia. 41. pp. 187–224. doi:10.1017/S0068113X10000176.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vindolanda tablets. |

- Item record at the British Museum, number P&EE 1989 6-2 74.

- Vindolanda Tablets Online, online catalogue of Vindolanda Tablets by CSAD, University of Oxford

- Vindolanda Tablets Online II, updated catalogue of Vindolanda Tablets by CSAD, University of Oxford