Michigan State University Vietnam Advisory Group

The Michigan State University Vietnam Advisory Group (commonly known as the Michigan State University Group and abbreviated MSUG) was a program of technical assistance provided to the government of South Vietnam as an effort in state-building by the U.S. Department of State.[1]

From 1955 to 1962, under contract to the International Cooperation Administration in Washington and the Vietnamese government in Saigon, faculty and staff from Michigan State University consulted for agencies of the Ngô Đình Diệm regime. The group advised and trained Vietnamese personnel in the disciplines of public administration, police administration, and economics. MSUG worked autonomously from most U.S. government agencies, had unmatched access to the presidency, and even assisted in writing the country's new constitution.[2] Several of its proposals were undertaken by the Vietnamese government and had positive results for the people of Vietnam. However, the group had limited influence on Diệm's decision-making and on the course of events in Vietnam, and publications by dissatisfied faculty led to Diệm's termination of the contract.

When implications later arose that the Central Intelligence Agency had infiltrated MSUG as a front for covert operations, the technical assistance program became a cause célèbre in the early years of the anti-war movement.

Project instigation and inception

During his self-imposed exile in the early 1950s, Ngô Đình Diệm met and befriended Wesley R. Fishel, a former military language specialist with a doctorate in international relations from the University of Chicago. Fishel was "impressed [by] Diệm's anticommunist and sociopolitical reform views, and the two men corresponded frequently".[3] When Fishel was hired in 1951 as an assistant professor of political science at Michigan State University, he invited Diệm to join him.[4] Two years later, as assistant director of the university's Governmental Research Bureau, Fishel appointed Diệm as the bureau's Southeast Asian consultant.[5]

The result was symbiotic: Diệm's visit to the United States enabled him to build up the political support he needed to be installed as the prime minister of South Vietnam in July 1954; in turn Fishel became one of Diệm's closest advisors and confidants.[6] At Fishel's suggestion, and already well aware of MSU's capabilities, Diệm requested that part of his aid package from the U.S. International Cooperation Administration include a "technical assistance" contract with Michigan State. MSU was thereby asked to use its expertise to help stabilize Vietnam's economy, improve the government bureaucracy, and control an ongoing communist insurgency.[7]

Michigan State, the pioneer land-grant university, had since its founding believed in turning theory into praxis; for example, its agricultural extension service made the results of its research available to farmers throughout Michigan for their practical use. Because of this emphasis on practical education and community involvement, the school justifiably claimed that "the state is our campus".[8] University President John A. Hannah in particular was a major proponent of the so-called service-oriented institution; to him, it was a logical next step to expand that role internationally, and declare without intended hyperbole that "the world is our campus".[9]

When the request for assistance came through U.S. government channels, the staunchly anticommunist Hannah was deeply interested in pursuing the contract. He sent a small evaluation contingent to Vietnam, consisting of three department chairmen that would be involved—Edward W. Weidner (political science), Arthur F. Brandstatter (police administration), and Charles C. Killingsworth (economics)—along with James H. Dennison, head of university public relations and Hannah's administrative assistant.[10] After a brief, two-week visit, the quartet reported in October 1954 that a state of emergency existed in Vietnam, and recommended that the project should be immediately undertaken. The report stated that although the short preparation time could lead to mistakes, it was "important... to get a program under way that ha[d] at least a reasonable chance of success".[11] Hannah approved the contract, forming the Michigan State University Group, which would operate under the authority of the U.S. Embassy's United States Operations Mission (USOM). Hannah also confirmed Weidner's recommendation that Fishel be appointed project head, a position Fishel held from the start of the project until early 1958.[12]

MSUG personnel had a variety of reasons for volunteering for this overseas service, each a reflection of the university's motivations for the entire MSUG project: as a moral obligation, to support a struggling young nation; as an instrument of U.S. foreign policy, to stanch the growth of "communist imperialism"; and as an academic exercise, to test their theoretical notions in a real-world "laboratory".[13] A "hardship" pay incentive and other allowances that nearly doubled a professor's salary (tax free), along with the prospect of personal advancement within the ranks of academia, were also persuasive.[14]

Phase One: 1955–57

The initial two-year contract commenced when the first contingent of professors and staff arrived in Saigon on May 20, 1955.[15] They found a city embroiled in a dissident uprising by Bình Xuyên forces, with shelling and street fighting that threatened not only Diệm's official residence but also the hotel where MSUG personnel were temporarily housed. At the height of the disturbances, hotel rooms were ransacked and looted, and some professors lost all of their possessions.[16] MSUG's intended academic programs were put on hold and their focus quickly turned toward improving regional government administration and police services.[17][18]

Commissariat of Refugees

Of immediate concern to Diệm was the social upheaval caused by some 900,000 people fleeing the communist North during the 300-day "free movement" period set by the 1954 Geneva Accords.[19] This massive influx required both resettlement and infrastructure-building services, which were provided by the government agency known as COMIGAL (Commissariat of Refugees; the acronym is from its French name). MSUG consulted for COMIGAL to such an extent during the first months of the program that other pursuits fell by the wayside.[20]

One of MSUG's proposals with positive results was the idea of decentralized bureaucracy for COMIGAL. By scattering small offices throughout the villages, COMIGAL was able to improve the responsiveness of those offices; funding for infrastructure projects was generally approved by Saigon in less than two weeks. Decentralization also enabled the offices to work directly with local leaders, who as a result felt that their input and participation were important.[21]

On the other hand, MSUG was unable to convince Diệm of the validity of the land claims made by the Montagnards, indigenous tribesmen in Vietnam's Central Highlands. Thousands of refugees—with government approval and encouragement—became permanent squatters on land "already cleared by highlanders for planting".[22] Part of Diệm's intent with this placement was to create a "human wall" of sympathetic, mostly Catholic settlers against communist infiltration from North Vietnam and nearby Cambodia. However, both the Montagnards and the majority Buddhists resented being governed by a Catholic regime, a minority religious group that they saw as unabashedly colonial. This opposition and Diệm's ruthless suppression pushed these groups toward further insurgency and, ultimately, communist rule.[23]

National Institute of Administration

Even as its time was monopolized by refugee assistance, the MSU Group pursued a portion of its academic goals. As the "public administration" facet of its contract, MSUG designed, financed, and implemented an expansion of the National Institute of Administration (NIA), a civil servant training school. NIA had started out as a two-year training school in the resort city of Da Lat in January 1953. Under MSUG recommendation, the school was moved to Saigon and gradually extended into a four-year program.[24]

Along with its assistance in developing the new Saigon campus and teaching classes, MSUG was instrumental in a substantial expansion of the NIA library, which by 1962 held more than 22,000 books and other documents.[25] The library was considered one of MSUG's greatest successes, and the NIA affiliation was the longest-lasting of the MSUG projects. However, the library's usefulness suffered from the simple fact that most of its documents were in English, rather than Vietnamese or French; and by the end of the MSUG contract the library was threatened by restricted accessibility, poor maintenance, and a lack of qualified Vietnamese personnel to staff it.[26]

Police administration

The most influential—and ultimately, controversial—aspect of MSUG technical assistance was in the field of police administration, where the group supplied not only consulting and training services, but also material aid.[27] In general, MSUG was responsible for distributing U.S. aid, provided through USOM, until 1959 when USOM established its own police staff.[28] MSUG staff acted as consultants to determine the needs of the police groups—and then tranacted the procurements themselves. The matériel included "revolvers, riot guns, ammunition, tear gas, jeeps and other vehicles, handcuffs, office equipment, traffic lights, and communications equipment".[29]

MSUG then trained Vietnamese personnel in the use and maintenance of this equipment. In general, MSUG trained instructors, who could then teach others; direct instruction, except in special cases like revolver training for the presidential guard, "was done only as a temporary expedient".[30] The police administration project was largely successful in this, since the training was based in hands-on demonstration and thus much more immediate and tangible. Also, the MSUG-taught Vietnamese instructors rapidly assumed training themselves. At the same time, classroom sessions in the principles of police procedure and theory suffered from a number of problems that limited their success. Few MSUG professors spoke Vietnamese or French, leading to a translation delay and information loss. In addition, American-style lectures were a source of dissonance for a student body raised on the French juridical system. (This was also an issue in NIA classes taught by MSUG staff.)[31][32]

Police administration consultation and training was most effective with the Sûreté, Vietnam's national law enforcement agency, in part because the majority of equipment was delivered to this agency. By the same token, municipal police departments (who received less equipment) were less affected—the greatest local improvement was in traffic control in Saigon. With regard to the civil guard, there was almost no effect.[33]

The civil guard was a 60,000-man paramilitary organization that MSUG hoped to reform into something resembling a U.S. state police outfit, an organization familiar to the professors. This would have entailed a primarily rural organization whose members would live in the communities they served. However, Saigon and the U.S. Military Assistance Advisory Group preferred that the civil guard be a more heavily armed paramilitary force, organized into regiments and living in garrisons, that could exercise national police duties and support the national army. As a result of this impasse, very little of the equipment that MSUG had planned for the civil guard was distributed until 1959, leaving the civil guard unprepared when major communist insurgency action began that same year.[34]

Staffing issues

One of MSUG's drawbacks was that in many cases the university lacked the manpower to staff the project and continue its scheduled classes in East Lansing. This was the case throughout MSUG, and the group was obliged to hire extensively outside the university to fulfill its contract with Vietnam, often giving the new staffers academic rank (generally assistant professor or lecturer).[35] The staffing issue had perhaps its most significant ramifications in the police administration division. Although Michigan State's School of Police Administration and Public Safety was "internationally recognized during the cold war era",[36] it lacked experience in the much-needed areas of counterespionage and counterinsurgency, and department head Arthur Brandstatter hired new personnel accordingly. At the height of the police administration project, only four of its thirty-three advisors had been Michigan State employees prior to MSUG, and many had never even visited the East Lansing campus.[37]

As it turns out, several of these police advisors also worked for the Central Intelligence Agency. They formed a separate group, establishing their own office apart from the rest of the police administration staff in MSUG's Saigon headquarters, "and were responsible only to the American Embassy in Saigon".[38] The CIA members worked closely with a special security unit of the Sûreté between 1955 and 1959. Although they were nominally under the aegis of MSUG, the specifics of their activities remained unknown to MSUG throughout. (MSUG files "support [the] contention that the agents were not spies";[39] CIA records remain classified to this day.)

The existence of the CIA group was not hidden from MSUG staff; on the contrary, it was common knowledge to the professors, if not openly discussed. A 1965 overview of the project was quite matter-of-fact about it: when MSUG "compelled USOM to establish a public safety division of its own in July, 1959[,] USOM also absorbed at this time the CIA unit that had been operating within MSUG".[40] This almost parenthetical statement would later provide the impetus for a sensational exposé.

Phase Two: 1957–59

The two-year contract was renewed in 1957. This second phase of MSUG was marked by an increased scope of operations, especially in the educational program, while its security commitments grew as well. "This was the period of the ubiquitous Michiganders."[41] Yet even as its operations increased, with a staff that included a project-wide peak of fifty-two Americans and about 150 Vietnamese,[41] MSUG operated under a level of reduced influence. In early 1958, Wesley Fishel concluded his tenure as program chief and returned to the United States.[42] With Fishel's departure came the end of the three-a-week breakfasts at the president's home that the professor had enjoyed with Diệm; without such direct access to the presidential ear, MSUG's sway with the administration was significantly curtailed. At the same time, the Vietnamese government had begun to solidify its power over the country, and as such it "lost much of its ardor for innovation".[42]

After 1958, the police administration role was almost entirely advisory, as the MSUG-trained Vietnamese instructors "by then were running their own show".[30] As advisors, MSUG helped the Sûreté—which by this time had been renamed the Vietnamese Bureau of Investigation, in an attempt to lessen the negative public image of that special police agency—to establish a national identification card, a program launched in 1959.[43]

Phase Three: 1959–62

The third contract encompassed a fraction of the previous contracts; MSUG work was almost exclusively related to the NIA and academic pursuits.[40] In part this was because USOM initiated its own police advisory unit and took over this role from MSUG, especially the work with the civil guard, which had its hands full fighting communist guerrillas.

The 1959 contract renewal also contained a clause that illustrates Diệm's increasing sensitivity to criticism: it stated that MSUG staffers' personal records and notes would not be used "against the security or the interests of Vietnam".[44] This stipulation ran contrary to the notion of academic freedom, and some professors chose to ignore it. For example, Robert Scigliano, an MSU political scientist who served as assistant project chief during 1957–1959, wrote an article in 1960 concerning the political parties of South Vietnam that called attention to Diệm's suppression of the opposition. Diệm was sufficiently irked by the article that he saw fit to mention it to MSU President Hannah when the latter visited Vietnam in early 1961, saying it "was not the kind of thing he liked to see MSU personnel writing".[44]

The NIA, in early 1961, made a formal request for a three-year extension past June 30, 1962, the end of the third MSUG contract. MSU expressed its willingness to pursue a small project focused solely on the Institute, but this was not to be.[44]

Dissent and dismissal

As the project progressed, the professors' initial optimism gave way to pragmatic considerations that often left them frustrated and disillusioned. MSUG frequently found its well-intentioned advice either ignored outright, or co-opted in practice; in one example among many, Diệm used the Sûreté's national identification card registry to crack down on his dissenters.[45] As a result, some professors returned home from their tours of duty and began to write articles critical of the Diệm regime and U.S. involvement in Vietnam. Two appeared in The New Republic magazine in 1961 and led to the end of MSUG.

The first, by Adrian Jaffe, visiting professor of English at the University of Saigon, and Milton C. Taylor, an MSUG economist,[46] was titled "A Crumbling Bastion: Flattery and Lies Won't Save Vietnam" and appeared in June 1961. It was a scathing indictment of the Diệm regime. Although Jaffe and Taylor played coy in the article by not naming Fishel or MSU—as if their academic affiliations as stated in a first-page sidebar were not a dead giveaway—they pulled no punches when it came to Diệm and his family. "The Vietnamese Government is an absolute dictatorship, run entirely by the President, with assistance of his family.... [It] sets a modern-day record for nepotism."[47]

Then Frank C. Child, an MSUG economist who spent two years as a consultant on the project while traveling extensively throughout South Vietnam, wrote "Vietnam—The Eleventh Hour", published in December 1961. It went a step further from Jaffe and Taylor by suggesting openly that "a military coup may be the only means" of saving Vietnam.[48]

These articles enraged Diệm, who demanded that the professors be censured by Michigan State. The university administration was reluctant, since to do so would be an infringement on academic freedom. On the other hand, MSU did not want to lose the lucrative contract with South Vietnam, so it offered that MSUG would be more cautious in its staff selection, choosing only those who promised to abide by the terms of the contract, and who would only "write scholarly, scientific studies and not sensational, journalistic articles."[49]

Diệm, however, would not be swayed, and demanded the termination of the project. The group left Vietnam in June 1962.

Exposé

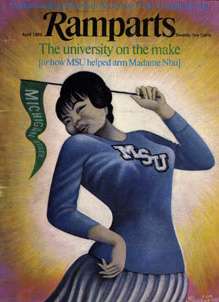

Four years after MSUG was disbanded, an exposé titled "The University on the Make" appeared in Ramparts magazine. Editors Warren Hinckle, Robert Scheer, and Sol Stern wrote the article in collaboration with economist Stanley K. Sheinbaum, who had served as MSUG's home-campus project coordinator from 1957 until his departure from the university "for various reasons" in 1959.[51][52] Drawing from the Jaffe–Taylor articles and Sheinbaum's disenchantment with the project, the article painted a vivid portrait: Fishel as an ambitious "operator" with more power and influence with Diệm than the U.S. Ambassador; MSU as a "parvenu institution" willing to trade academic integrity for a prominent role on the world stage; and MSUG as a knowing—and willing—conspirator with the CIA.[53]

The Ramparts article, though heavily based on the 1965 book Technical Assistance in Vietnam, for the most part ignored the academic-study and instructor-training aspects of the police administration project. Rather than mention the establishment of the National Police Academy and the Sûreté high command school, where MSUG staff "planned curricula and served as classroom lecturers",[30] instead it implied that the project entailed little more than firearms training and handcuffs disbursal. It also focused closely on the CIA connection, and extrapolated the line "the University group refused to provide cover for this unit [after 1959]"[40] to mean that MSUG had previously provided cover for "cloak-and-dagger" work. In its conclusion, the article effectively reduced the entire MSUG project to a single incendiary line: "what the hell is a university doing buying guns, anyway?"[54]

The Ramparts article was deliberately muckraking, and distorted and dramatized many of its "facts"; some of these were later admitted to be untrue.[55] Nevertheless, it reached its intended audience, and offered powerful fodder for the nascent anti-war movement.[56] Along with the glaring issue of the CIA operating under the guise of a university, an increasing number of American students and faculty began to question the use of institutes of higher learning as the instruments of U.S. foreign policy.[57]

Aftermath

Michigan State University, like many American universities, continued to contract for overseas technical assistance programs, but never again on the scale of the Michigan State University Group. In the end, MSU saw very little academic benefit from its "Vietnam adventure". No new courses or special study programs were started at the home campus, and out of eighteen professors that were assigned from East Lansing, five did not return to the campus, and four others left within two years of their return.[58] One indirect result was the Office of International Studies and Programs, created in 1956 to provide campus coordination and administrative support for the Vietnam project (as well as projects in Colombia, Brazil, and Okinawa).[59] In 1964 the office received a new home, today known as the International Center; the building cost approximately $1.2 million and was financed with a portion of the $25 million that MSUG received from the U.S. government during its seven-year Vietnam contract (most of which went toward matériel, salaries, field expenses, and administrative costs).[15][60][61][62]

Amid increasing anti-war protest, President John Hannah departed MSU in 1969 to head the United States Agency for International Development—the successor to the International Cooperation Administration that had initiated the MSUG contract. Although his abrupt departure from MSU might suggest otherwise, Hannah did not doubt the project's propriety; years later, he stated, "We never felt any need for the University to apologize... for what we tried to do in Vietnam. I think that if Michigan State were to face the same choice again in the same context, it might well agree to assist the U.S. Government as we did then."[63] Hannah's interim replacement as president was economics professor Walter Adams, who had long questioned the efficacy of university technical assistance programs and who in 1961 had encouraged Jaffe and Taylor to publish "A Crumbling Bastion".[64][65]

Professor Wesley Fishel was demonized at MSU for his role in the project. Although by 1962 he had become "disenchanted by Diệm's dictatorial policies",[66] Fishel could not live down a strongly pro-Diệm article he had written in 1959 titled "Vietnam's Democratic One-Man Rule".[67] Campus protesters singled him out in their placards and chants, and disrupted his classes.[68] Fishel's notoriety and the strain of constantly defending his actions were speculated to have contributed to health problems, and he died in April 1977 at the age of 57.[69]

Notes

- ↑ Ernst (1998), p. xii.

- ↑ Scigliano and Fox (1965), p. 2.

- ↑ Ernst (1998), pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Ernst (1998), p. 9; Scigliano and Fox (1965), p. 1, state that Fishel was already an assistant professor at Michigan State when he met Diệm in July 1950.

- ↑ Ernst (1998), p. 10.

- ↑ Ernst (1998), p. 141.

- ↑ Ernst (1998), p. 11.

- ↑ Adams (1971), p. 171.

- ↑ Ernst (1998), p. 6.

- ↑ Ernst (1998), pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Ernst (1998), p. 12.

- ↑ Ernst (1998), pp. 13, 50.

- ↑ Adams (1971), pp. 172–173.

- ↑ Adams (1971), p. 173.

- 1 2 Scigliano and Fox (1965), p. 4.

- ↑ Smuckler (2003), pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Scigliano and Fox (1965), p. 6.

- ↑ Ernst (1998), pp. 14–16.

- ↑ Ernst (1998), p. 21.

- ↑ Ernst (1998), p. 22.

- ↑ Ernst (1998), p. 25.

- ↑ Ernst (1998), p. 32.

- ↑ Ernst (1998), pp. 34–35.

- ↑ Scigliano and Fox (1965), p. 32.

- ↑ Ernst (1998), p. 31.

- ↑ Scigliano and Fox (1965), p. 37.

- ↑ Scigliano and Fox (1965), p. 14.

- ↑ Scigliano and Fox (1965), p. 15.

- ↑ Scigliano and Fox (1965), p. 16.

- 1 2 3 Scigliano and Fox (1965), p. 18.

- ↑ Scigliano and Fox (1965), p. 19.

- ↑ Ernst (1998), pp. 64–65.

- ↑ Scigliano and Fox (1965), pp. 21–22.

- ↑ Scigliano and Fox (1965), p. 17.

- ↑ Adams (1971), p. 175.

- ↑ Ernst (1998), p. 63.

- ↑ Ernst (1998), p. 81.

- ↑ Scigliano and Fox (1965), p. 21.

- ↑ Ernst (1998), p. 127.

- 1 2 3 Scigliano and Fox (1965), p. 11.

- 1 2 Scigliano and Fox (1965), p. 8.

- 1 2 Scigliano and Fox (1965), p. 51.

- ↑ Scigliano and Fox (1965), p. 20.

- 1 2 3 Scigliano and Fox (1965), p. 53.

- ↑ Ernst (1998), p. 84.

- ↑ Ernst (1998), p. 120.

- ↑ Jaffe and Taylor (1961), p. 17.

- ↑ Child (1961), p. 16.

- ↑ Scigliano and Fox (1965), p. 53, quoting a letter from Alfred L. Seelye, Dean of the College of Business and Public Service, to Nguyễn Đình Thuận, Secretary of State at the Presidency, Republic of Vietnam, February 2, 1962.

- ↑ "With Cap & Cloak in Saigon". Time. 87 (16). 22 April 1966. Retrieved 3 April 2008.

- ↑ Smuckler (2003), p. 29.

- ↑ Ernst (1998), p. 123.

- ↑ Hinckel et al. (1966), pp. 11–22.

- ↑ Hinckel et al. (1966), p. 22.

- ↑ Ernst (1998), pp. xiii, 126, 129.

- ↑ Sturm, Daniel (5 May 2004). "Where is McPherson leading Moo U? Critics see comparisons to MSU's Vietnam-era role". Lansing City Pulse. Retrieved 31 October 2009.

- ↑ Ernst (1998), p. xiv.

- ↑ Scigliano and Fox (1965), pp. 68–70.

- ↑ Dressel (1987), p. 268.

- ↑ Taylor and Jaffe (1962), p. 28.

- ↑ "Building Information". Michigan State University Physical Plant. 2008. Retrieved 23 March 2008.

- ↑ Ernst (1998), p. 131.

- ↑ Dressel (1987), p. 279.

- ↑ Adams and Garraty (1960).

- ↑ Ernst (1998), pp. 132, 120.

- ↑ Ernst (1998), p. 121.

- ↑ Taylor and Jaffe (1962), p. 29.

- ↑ Ernst (1998), p. 131–132.

- ↑ Ernst (1998), p. 133.

References

- Adams, Walter; John A. Garraty (1960). Is the World Our Campus?. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press. ISBN 0-87013-047-1.

- Adams, Walter (2003) [1971]. The Test. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press. ISBN 0-87013-648-8.

- Child, Frank C. (4 December 1961). "Vietnam—The Eleventh Hour". The New Republic. 145: 14–16.

- Dressel, Paul L. (1987). College to University: The Hannah Years at Michigan State, 1935–1969. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press. ISBN 0-940635-00-3.

- Ernst, John (1998). Forging a Fateful Alliance: Michigan State University and the Vietnam War. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press. ISBN 0-87013-478-7.

- Hinckle, Warren; Robert Scheer; Sol Stern; Stanley K. Sheinbaum (April 1966). "The University on the Make". Ramparts. 4: 11–22. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- Jaffe, Adrian; Milton C. Taylor (19 June 1961). "A Crumbling Bastion: Flattery and Lies Won't Save Vietnam". The New Republic. 144: 17–20.

- Scigliano, Robert; Guy H. Fox (1965). Technical Assistance In Vietnam: The Michigan State University Experience. New York: Praeger.

- Smuckler, Ralph H. (2003). A University Turns to the World: A Personal History of the Michigan State University International Story. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press. ISBN 0-87013-646-1.

- Taylor, Milton C.; Adrian Jaffe (5 March 1962). "The Professor–Diplomat: Ann Arbor and Cambridge Were Never Like This". The New Republic. 146: 28–30.

External links

- MSUG-produced documents available through the U.S. Agency for International Development's Development Experience Clearinghouse