West Potomac Park

|

West Potomac Park | |

|

View of West Potomac Park (left) from the Washington Monument | |

| |

| Location | Bounded by Constitution Ave., 17th St., Independence Ave., Washington Channel, Potomac River, and Rock Creek Park, N.W. |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 38°53′9.6″N 77°2′49.2″W / 38.886000°N 77.047000°WCoordinates: 38°53′9.6″N 77°2′49.2″W / 38.886000°N 77.047000°W |

| Area | 394.9 acres (159.8 ha) |

| Built | 1881-1912 |

| NRHP Reference # | 73000217[1] |

| Added to NRHP | November 30, 1973[2] |

West Potomac Park is a U.S. national park in Washington, D.C., adjacent to the National Mall. It includes the parkland that extends south of the Lincoln Memorial Reflecting Pool, from the Lincoln Memorial to the grounds of the Washington Monument. The park is the site of many national landmarks, including the Korean War Veterans Memorial, Jefferson Memorial, Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial, George Mason Memorial, Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial and the surrounding land on the shore of the Tidal Basin, an artificial inlet of the Potomac River created in the 19th century that links the Potomac with the northern end of the Washington Channel. West Potomac Park is administered by the National Park Service.

Creation of the park

Almost none of the National Mall west of the Washington Monument grounds and below Constitution Avenue NW existed prior to 1882.[3] After terrible flooding inundated much of downtown Washington, D.C., in 1881, Congress ordered the Army Corps of Engineers to dredge a deep channel in the Potomac and use the material to fill in the Potomac (creating the current banks of the river) and raise much of the land near the White House and along Pennsylvania Avenue NW by nearly 6 feet (1.8 m).[4] This "reclaimed land" — which included West Potomac Park, East Potomac Park, the Tidal Basin — was largely complete by 1890, and designated Potomac Park by Congress in 1897.[5] Congress first appropriated money for the beautification of the reclaimed land in 1902, which led to the planting of sod, bushes, and trees; grading and paving of sidewalks, bridle paths, and driveways; and the installation of water, drainage, and sewage pipes.[6]

Cherry trees

The famous sakura (Japanese cherry trees) of Washington line the Tidal Basin and are the main attraction at the National Cherry Blossom Festival in early spring, when the cherry blossoms bloom. Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore, upon returning to Washington from a visit to Japan, initiated the idea of cherry trees in Washington, approaching the Superintendent of Public Building and Grounds (then Colonel Spencer Cosby) in 1885. Her idea was rejected; over the next 24 years, Scidmore approached every new superintendent, but the idea never came to fruition. In 1906, Dr. David Fairchild, a botanist who worked for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, imported 75 flowering cherry trees and 25 single-flowered weeping types from the Yokohama Nursery Company in Japan. Fairchild planted these trees on a hillside on his own property in Chevy Chase, Maryland, testing their hardiness in the Washington area. In 1907, pleased with the success of the trees, Fairchild and his wife began to promote Japanese flowering cherry trees as the ideal type of tree to plant along avenues in the Washington area. Friends of family also became interested, and on September 26, arrangements were completed with the Chevy Chase Land Company to order 300 Oriental cherry trees for the Chevy Chase area.

In 1908, Fairchild gave cherry saplings to boys from each school in the District to plant in schoolyards on Arbor Day. In closing his Arbor Day speech, Fairchild expressed a vision that the "Speedway" (the present day corridor of Independence Avenue in West Potomac Park) be transformed into a "Field of Cherries". In attendance was Eliza Scidmore, whom afterwards he referred to as a great authority on Japan. In 1909, Scidmore decided to try to raise the money required to purchase the cherry trees and then donate the trees to the city. Scidmore sent a note outlining her new plan to the new First Lady, Helen Herron Taft—the wife of President William Howard Taft— who had once lived in Japan and was familiar with the beauty of the flowering cherry trees. Two days later, the First Lady responded:

- The White House, Washington

- April 7, 1909

- Thank you very much for your suggestion about the cherry trees. I have taken the matter up and am promised the trees, but I thought perhaps it would be best to make an avenue of them, extending down to the turn in the road, as the other part (beyond the railroad bridge Ed.) is still too rough to do any planting. Of course, they could not reflect in the water, but the effect would be very lovely of the long avenue. Let me know what you think about this.

- Sincerely yours,

- Helen H. Taft

On April 8, the day after Taft's letter, Dr. Jokichi Takamine, the Japanese chemist famous as the discoverer of adrenaline and takadiastase, was in Washington with Midzuno, the Japanese consul in New York City. When told Washington was to have Japanese cherry trees planted along the Speedway, he asked whether the First Lady would accept a donation of an additional 2,000 trees. Midzuno thought it was a fine idea and suggested the trees be given in the name of the capital city of Tokyo. Takamine and Midzuno met with the Helen Taft, who accepted the offer.

On April 13, five days after the First Lady's request, the Superintendent of Public Building and Grounds ordered the purchase of 90 cherry trees (Prunus serrulata) of the Fugnezo variety from Hoopes Brothers and Thomas Company in West Chester, Pennsylvania. The trees were planted along the Potomac River from the present site of the Lincoln Memorial south toward East Potomac Park. After planting, it was discovered that the trees were not correctly named, and were not of the Fugnezo variety, but instead of the Shirofugen cultivar (cultivated variety). These trees have since disappeared.

Some months later, on August 30, the Japanese embassy informed the U.S. Department of State that Tokyo intended to donate 2,000 cherry trees to the United States to be planted along the Potomac River. On December 10, the trees arrived in Seattle, and on January 6, 1910 arrived in the capital. However, an inspection team for the Department of Agriculture discovered to everyone's dismay that the trees were infested with insects, roundworms, and plant diseases. To protect American growers, the department concluded that the trees must be destroyed. On January 28, Taft gave permission to destroy the trees, and they were burned. This diplomatic setback resulted in letters from Secretary of State and the representatives to the Japanese ambassador, expressing deep regret of all concerned. Dr. Takamine, meeting the bad news with goodwill, again donated the costs for the trees in 1912, whose number he now increased to 3,020. The seeds for these trees were taken in December 1910 from the famous collection on the bank of the Arakawa River in Adachi Ward, a suburb of Tokyo, and grafted on specially selected understock produced in Itami City in Hyōgo Prefecture.

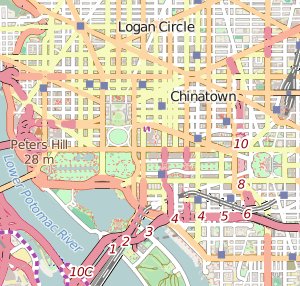

Map of West Potomac Park

|

Color-enhanced USGS satellite image of West Potomac Park, taken April 26, 2002.

Key to image:

|

See also

References

- ↑ National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ East and West Potomac Parks. Nomination Form for Federal Properties. Form 10-306 (Oct. 1972). National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. November 30, 1973. Accessed 2013-04-15.

- ↑ Berg, Scott W. "The Beginning of the Road." Washington Post. August 31, 2008. Accessed 2013-04-15.

- ↑ Tindall, p. 396; Gutheim and Lee, p. 94-97; Bednar, p. 47.

- ↑ Gutheim and Lee, p. 96-97.

- ↑ Report of the Chief of Engineers..., p. 1891. Accessed 2013-04-15.

Bibliography

- Bednar, Michael J. L'Enfant's Legacy: Public Open Spaces in Washington, D.C. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006.

- Gutheim, Frederick A. and Lee, Antoinette J. Worthy of the Nation: Washington, D.C., From L'Enfant to the National Capital Planning Commission. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006.

- Report of the Chief of Engineers. War Department Annual Reports, 1917. Vol. 2. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1918.

- Tindall, William. Standard History of the City of Washington From a Study of the Original Sources. Knoxville, Tenn.: H.W. Crew & Co., 1914.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to West Potomac Park. |