West Side Line (NYCRR)

The West Side Line, also called the West Side Freight Line, is a railroad line on the west side of the New York City borough of Manhattan. North of Penn Station, from 34th Street, the line is used by Amtrak passenger service heading north via Albany to Toronto; Montreal; Niagara Falls; Rutland, Vermont; and Chicago. South of Penn Station, a 1.45-mile (2.33 km) elevated section of the line abandoned since 1980 (popularly known as the High Line) has been transformed into an elevated park. The south section of the park from Gansevoort Street to 20th Street opened in 2009 and the second section up to 30th Street opened in 2011.[1]

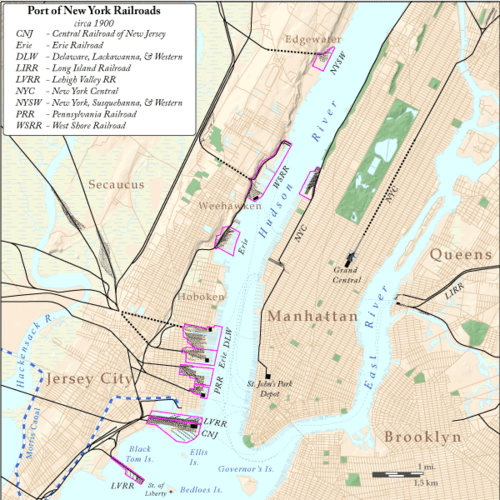

Hudson River Railroad

The West Side Line was built by the Hudson River Railroad, which completed the forty miles (64 km) to Peekskill on 29 September 1849, opened to Poughkeepsie by the end of that year, and extended to Albany in 1851. The city terminus was at the junction of Chambers and Hudson Streets; the track was laid along Hudson, Canal, and West Streets, to Tenth Avenue, which it followed to the upper city station at 34th Street. Over this part of the right-of-way, the rails were laid at grade along the streets, and since by the corporation regulations locomotives were not allowed, the cars were drawn by a dummy engine, which, according to an 1851 description, consumed its own smoke. While passing through the city the train of cars was preceded by a man on horseback known as a "West Side cowboy" or "Tenth Avenue cowboy" who gave notice of its approach by blowing a horn.[2][3]

At 34th Street the right-of-way curved into Eleventh Avenue, the dummy engine was detached, and the regular locomotive took the train. As far as 60th Street, the track was at street level. The first cut was at Fort Washington Point. The railroad crossed Spuyten Duyvil Creek on a drawbridge; a fatal wreck occurred there 13 January 1882 when the Atlantic Express, stopped on the line, was rear-ended by a local train, telescoping the last two palace cars, where the stoves and lamps were upset and ignited the woodwork and upholstery.[4]

In 1867 the New York Central Railroad and Hudson River Railroad were united by Cornelius Vanderbilt, being merged in 1869 to form the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad. The railroad acquired the former Episcopal church's St. John's Park property and built a large freight depot at Beach and Varick streets which opened in 1868. The tracks south to Chambers Street were then removed.[5] In 1871, the Spuyten Duyvil and Port Morris Railroad opened, and most passenger trains were rerouted into the new Grand Central Depot via that line along the northeast bank of the Harlem River and the New York and Harlem Rail Road, also part of the New York Central system. The old line south of Spuyten Duyvil remained for freight to the docks along Manhattan's west side and minimal passenger service to the West Side Station on Chambers Street (used until 1916).

Grade separation

As the city grew, congestion worsened on the west side. Eventually plans were drawn up for a grade-separated line. The West Side Elevated Highway was built with the line's grade separation in the 1930s. Work on the highway – named for Manhattan Borough President Julius Miller, who championed it – began in 1925, and the first section was dedicated June 28, 1934. This included a new elevated eight-track freight terminal at St. John's Park, located several blocks north of the old one, with a south edge at Spring Street. North of there, an elevated structure carried two tracks north on the west side of Washington Street, curving onto the east side of Tenth Avenue at 14th Street, then crossing Tenth Avenue at 17th Street and heading north along its west side. Just south of the Pennsylvania Station rail yard at 31st–33rd Streets, the line turned west on the north side of 30th Street, then north just east of the West Side Highway. The northernmost bridge crossed 34th Street, and a temporary alignment took it back to Eleventh Avenue at 35th Street. The elevated line was built through the second or third floors of several buildings along the route; others were served directly by elevated sidings.[6][7]

In 1937 the tracks along Eleventh Avenue were bypassed by a below-grade line, passing under the 35th Street intersection and running north just west of Tenth Avenue before slowly curving northwest, passing under Eleventh Avenue at 59th Street and rejoining the original alignment.[6][7]

Around the same time, master builder and urban planner Robert Moses covered the line with an expansion of Riverside Park from 72nd Street north to 120th Street. His project, called the West Side Improvement, was twice as expensive as the Hoover Dam and created the Henry Hudson Parkway as well as the expansion of Riverside Park. North of the 1937 alignment, the Henry Hudson Parkway and Riverside Park were built above the tracks from 72nd Street north to near 123rd Street, creating a railroad tunnel through the park. The large 60th Street Yard served as the dividing point between the two-track realignment and a wider four-track line to the north. North of 123rd Street, the line became elevated between the Henry Hudson Parkway and Riverside Drive before returning to the surface and crossing under the Parkway to its west side near 159th Street. It continues along the shore of the Hudson River to the Spuyten Duyvil Bridge, a swing bridge across the Harlem Ship Canal (Spuyten Duyvil Creek), before merging with the Spuyten Duyvil and Port Morris Railroad just north of the bridge.[7]

In addition to serving the industrial and dock areas of the Lower West Side, the line was the primary route for produce and meat into New York, serving warehouses in the West Village, Chelsea, and the Meatpacking District, as well as serving the James Farley Post Office and private freight services.[8]

Donald Trump and Riverside South

The New York Central Railroad was merged into Penn Central in 1968 and Conrail in 1976. Conrail continued to operate freight along the West Side Line until the 1980s.

Donald Trump optioned the 60th Street Yard in 1974.[9] Riverside South, the development project he ultimately began there, was then the city's biggest private residential development; it faced opposition from many people living on the Upper West Side.[10] To obtain approval of his project, Trump agreed to substantially reduce the size of his ambitions,[11] build Riverside Park South on 23 acres (9.3 ha) of the yard,[12] and donate the park and the right-of-way for a relocated highway to the city.[13]

The line itself north of 31st Street was acquired by Amtrak. The southernmost part of the High Line (south of Bank Street) had been removed in the 1960s;[14] the structure from Bank to Gansevoort Streets was removed some 20 years later.[15] By mid-2005, the rest of the High Line was owned by CSX, which acquired it after the 1999 breakup of Conrail.[16]

Empire Connection

The Empire Connection allows Amtrak's passenger trains traveling on the Empire Corridor from Albany in upstate New York, and beyond, to enter Penn Station. Before its construction, Empire Corridor trains came into Grand Central Terminal, requiring passengers bound for Northeast Corridor trains to transfer to Penn Station via shuttle bus, taxicab or subway.[17]

When the West Side Yard for the Long Island Rail Road was built on the west side of Manhattan in 1986, a tunnel was built under it connecting Penn Station to the West Side Line just west of Eleventh Avenue, near the Javits Center. The project severed the southern portion of the West Side Line, whose viaduct was later repurposed as the High Line.[18] When additional funding later became available, one track along the northern part of the West Side Line was rebuilt for passenger service and named the Empire Connection. A short section of single track into Penn Station was electrified using third rail and overhead catenary, since diesel locomotives are not allowed in Penn Station's tunnels. North of 41st Street, the single track expands into two tracks and electrification on the line ends. A wye was constructed next to Track 2 (the westernmost track) to allow diesels to turn around. South of 49th Street, there is a crossover from Track 1 (the easternmost track) to Track 2, and another siding splits off Track 2 at 49th Street. The Empire Connection was double-tracked north of 39th Street to south of the Spuyten Duyvil Bridge in the mid-1990s.

On April 7, 1991, all of Amtrak's Empire Corridor trains began using the Empire Connection into Penn Station, ending service to Grand Central.[19] Besides being more convenient for transferring passengers, this saved Amtrak the expense of operating two stations in New York City.

Under the Penn Station Access project, Metro-North Railroad is studying ways it could also serve Penn Station. One alternative under study would run some Hudson Line commuter trains into Penn Station via the Empire Connection, possibly with new station stops at West 125th and West 62nd Streets.

The High Line park

In the early 1980s, as the connections to Penn Station were created, the line south of 34th Street was disconnected from the rest of the U.S. railway system. This portion of the line, entirely on an elevated viaduct, stood dormant for over thirty years. This viaduct, now called the High Line, has been turned into an elevated park which opened in phases from June 2009 to fall 2014.[20][21][22][23][24]

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ Construction Update: Section 2 Will Open in June | Friends of the High Line. Thehighline.org (2011-05-11). Retrieved on 2013-07-26.

- ↑ Hudson River and the Hudson River Rail-Road. Boston: Bradbury & Guild. 1851. p. 12. Retrieved 2015-09-18.

- ↑ Highline Photo of the Week West Side Cowboy

- ↑ "Fatal Disaster on the Hudson River Railroad". Frank Leslie's Weekly. January 21, 1882. Retrieved 2010-04-10.

- ↑ Joint Report of the New York, New Jersey Port and Harbor development Commission, 1917

- 1 2 L.H. Robbins, "Transforming the West Side: A Huge Project Marches On," New York Times, June 3, 1934

- 1 2 3 "NYC West Side Improvement". railroad.net. Archived from the original on March 1, 2000. Retrieved May 17, 2016.

- ↑ "RAILROAD.NET - New York Central's 1934 West Side Improvement". railroad.net.

- ↑ Bagli, Charles V. (2005-06-01). "Trump Group Selling West Side Parcel for $1.8 Billion". The New York Times. Retrieved 2016-05-17.

- ↑ Bruce Weber, "Debate on Trump's West Side Proposal," New York Times, July 22, 1992

- ↑ Alan Finder, "Trump Yields to Demands on Housing," New York Times, October 22, 1992.

- ↑ Vitullo-Martin, Julia (2004-01-19). "The West Side Rethinks Donald Trump's Riverside South". home.jps.net. Retrieved 2016-05-17.

- ↑ Robert Moses' Proposal, 1975 (image). home.jps.net. Accessed May 5, 2016.

- ↑ "The High Line". NYC Architecture.

- ↑ Amateau, Albert (April 30 – May 6, 2008). "Newspaper was there at High Line's birth and now its rebirth". The Villager. 77 (48). Retrieved August 12, 2011.

- ↑ Doyle, Chesney; Spann, Susan (2014). "Elevated Thinking: The High Line in New York City". Great Museums.

- ↑ Penn Station could be reached from the Empire Corridor, but only via an impractical route from the Bronx, via the New Haven Line, that then backtracked several miles to the north, to Pelham Manor, to the Northeast Corridor line.

- ↑ Voboril, Mary (March 26, 2005). "The Air Above Rail Yards Still Free". Newsday. New York.

- ↑ "Travel Advisory; Grand Central Trains Rerouted To Penn Station". The New York Times. April 7, 1991. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ↑ Marritz, Ilya (June 7, 2011). "As the High Line Grows, Business Falls in Love with a Public Park". WNYC. Retrieved 2011-06-08.

- ↑ Browne, Alex (June 7, 2011). "High Notes - New Art on the High Line". The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ↑ Pesce, Nicole Lyn (June 7, 2011). "Hotly anticipated second section of the High Line opens, adding 10 blocks of elevated park space". Daily News. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ↑ Battaglia, Andy (May 11, 2014). "Artist's 'Ruins' Rise on the High Line - WSJ.com". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ↑ "High Line at the Rail Yards". Friends of the High Line. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

Sources

- Scull, Theodore W. (August 1991). "Change at Penn Station: an opportunity". Trains.

- Johnston, Bob (June 1995). "New Amtrak cuts signal a long siege". Trains.

External links

- New York Central's 1934 West Side Improvement (1934 pamphlet)

- Abandoned Stations - Bronx Railroad Stations (includes the West Side Line in Manhattan)

- Metro-North Penn Station access study