Western Area Command (RAAF)

| Western Area Command | |

|---|---|

|

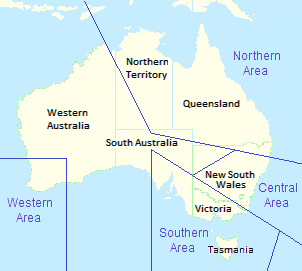

Provisional RAAF area command boundaries, February 1940 | |

| Active | 1941–56 |

| Allegiance | Australia |

| Branch | Royal Australian Air Force |

| Role |

Air defence Aerial reconnaissance Protection of adjacent sea lanes |

| Garrison/HQ | Perth |

| Engagements | World War II |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders |

Hippolyte De La Rue (1941–42) Raymond Brownell (1942–45) Colin Hannah (1945, 1946) Bill Garing (1946–48) William Hely (1951–53) |

Western Area Command was one of several geographically based commands raised by the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) during World War II. It was formed in January 1941, and controlled RAAF units located in Western Australia. Headquartered at Perth, Western Area Command was primarily responsible for air defence, aerial reconnaissance and protection of the sea lanes within its boundaries. Its aircraft conducted anti-submarine operations throughout the war, and attacked targets in the Dutch East Indies during the Borneo campaign in 1945. Western Area Command continued to operate following the end of the war, before its responsibilities were subsumed in 1954 by the RAAF's new functional command-and-control system; the headquarters was disbanded two years later.

History

World War II

Prior to World War II, the Royal Australian Air Force was small enough for all its elements to be directly controlled by RAAF Headquarters in Melbourne. After war broke out in September 1939, the Air Force began to decentralise its command structure, commensurate with expected increases in manpower and units.[1][2] Between March 1940 and May 1941, the RAAF divided Australia and New Guinea into four geographically based command-and-control zones: Central Area, Southern Area, Western Area, and Northern Area.[3] The roles of these area commands were air defence, protection of adjacent sea lanes, and aerial reconnaissance. Each was led by an Air Officer Commanding (AOC) responsible for the administration and operations of all air bases and units within his boundary.[2][3]

Western Area Command, headquartered in Perth, was formed on 9 January 1941 to control all RAAF units in Western Australia.[4] These included No. 14 (General Reconnaissance) Squadron, No. 25 (General Purpose) Squadron and No. 5 Initial Training School at RAAF Station Pearce; No. 9 Elementary Flying Training School at Cunderdin; and the soon-to-be-raised No. 4 Service Flying Training School at Geraldton.[5] RAAF Headquarters had maintained control of Western Australian units pending the area's formation.[6] Western Area's inaugural AOC was Group Captain (acting Air Commodore) Hippolyte "Kanga" De La Rue.[5][7] His senior air staff officer was Group Captain Alan Charlesworth. Headquarters staff numbered forty-one, including fifteen officers.[8] No. 14 Squadron, operating Lockheed Hudsons, and No. 25 Squadron, flying CAC Wirraways, were responsible for convoy escort and anti-submarine patrol.[9][10] Shortly after taking command, De La Rue lobbied RAAF Headquarters for a force of long-range Catalina flying boats to augment No. 14 Squadron's Hudsons, but none were made available.[11]

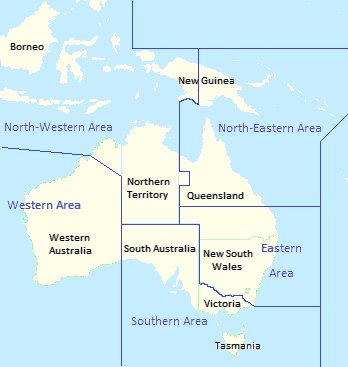

By mid-1941, RAAF Headquarters had determined to form training units in the southern and eastern states into semi-geographical, semi-functional groups separate to the area commands. This led to the establishment in August of No. 1 (Training) Group in Melbourne, covering Victoria, Tasmania and South Australia, and No. 2 (Training) Group in Sydney, covering New South Wales and Queensland; at the same time, Central Area was dissolved and its responsibilities divided between Southern and Northern Areas, and No. 2 (Training) Group.[12][13] Western Area, uniquely among the area commands, retained responsibility for training, as well as operations and maintenance, within its boundaries.[13] In November 1941, all available aircraft from Nos. 14 and 25 Squadrons, as well as eight Avro Ansons from No. 4 Service Flying Training School, took part in the search for HMAS Sydney after it was sunk by the German raider Kormoran; a Hudson and an Anson each located lifeboats bearing Kormoran's crew.[14][15] Following the outbreak of the Pacific War, Northern Area was split in January 1942 into North-Western and North-Eastern Areas, to counter separate Japanese threats to Northern Australia and New Guinea, respectively.[1][16] In May, a new area command, Eastern Area, was raised to control units within New South Wales and southern Queensland.[17] The same month, the Air Board proposed raising No. 3 (Training) Group and No. 8 (Maintenance) Group to control training and maintenance units in Western Australia but, though approved by the Federal government, this did not take place.[18] As of 31 May 1942, Western Area headquarters staff numbered 247, including seventy-two officers.[19]

No. 35 (Transport) Squadron, operating de Havilland Fox Moth and DH.84 Dragon aircraft, was raised under Western Area's control at Pearce on 4 March 1942.[20][21] No. 77 Squadron, equipped with P-40 Kittyhawks, was formed at Pearce on 16 March; it was at this time the only fighter squadron available to defend Perth and Fremantle, and De La Rue worked assiduously to prepare it for operations.[22] No. 6 Fighter Sector Headquarters, Perth, became operational on 2 May.[23][24] As of 20 April, operational authority over all RAAF combat infrastructure, including area commands, was invested in the newly established Allied Air Forces (AAF) Headquarters under South West Pacific Area Command (SWPA).[25][26] Some finetuning of Western Area's boundaries occurred in August: as well as the Northern Territory, North-Western Area was given responsibility for the portion of Western Australia north of a line drawn south-east from Yampi Sound to the Northern Territory border.[27] September 1942 saw the formation of RAAF Command, led by Air Vice Marshal Bill Bostock, to oversee the majority of Australian flying units in the SWPA.[28][29] Bostock exercised control of air operations through the area commands, although RAAF Headquarters continued to hold overarching administrative authority over all Australian units.[30] In November, construction began on an airfield under Western Area's control at Corunna Downs, near Port Hedland. Australia's closest air base to Surabaya, it would serve as a staging post for Allied bombers bound for targets in the Dutch East Indies, allowing them to avoid Japanese fighter stations between Darwin and Java.[31][32] De la Rue handed Western Area over to Air Commodore Raymond Brownell in December 1942; by the end of the month, headquarters staff numbered 488, including ninety-five officers.[33][34]

By April 1943, Western Area controlled four combat units: No. 14 Squadron, flying Bristol Beaufort reconnaissance-bombers out of Pearce; No. 25 Squadron, tasked with dive-bombing missions in Wirraways based at Pearce; No. 76 Squadron, flying P-40 Kittyhawks out of Potshot (Exmouth Gulf); and No. 85 Squadron, operating CAC Boomerang fighters from Pearce. The area command was also able to call on US Navy Catalinas of Patrol Wing 10, based at Crawley, for reconnaissance and anti-submarine missions.[35] The Beauforts and Catalinas flew several hundred maritime patrols during 1943.[36] In March 1944, Western Area went on high alert in response to concerns that a Japanese naval force would raid Western Australia. Perth was reinforced with Nos. 452 and 457 Squadrons, and Exmouth Gulf with Nos. 18, 31, and 120 Squadrons, but no attack ensued and the units were directed to return to their home bases.[37] The US Navy withdrew Patrol Wing 10 mid-year, curtailing Western Area's ability to conduct long-range maritime reconnaissance; No. 14 Squadron's fifteen serviceable Beauforts had to fly patrols of up to twenty-two hours in duration to search for German submarines reported in the area.[38][39] As of 31 May 1944, Western Area headquarters staff numbered 686, including 118 officers.[40]

Having converted to Vultee Vengeance dive bombers in August 1943, No. 25 Squadron moved from Pearce to Cunderdin in January 1945 and re-equipped with B-24 Liberator heavy bombers.[41] The Liberators were employed on anti-submarine patrol off Cape Leeuwin later that month, owing to No. 14 Squadron's Beauforts being fully committed to other tasks.[42] Between April and July, No. 25 Squadron provided Western Area's contribution to the Borneo campaign, supporting the Allied invasions of Tarakan, Labuan–Brunei and Balikpapan.[43] Staging through Corunna Downs, the Liberators bombed Japanese airfields in the Dutch East Indies that were within range of Tarakan, up until the day of the landings on 1 May.[44] They attacked Malang near Surabaya at night prior to the landings at Labuan, and conducted daylight raids against Java in the lead-up to the Balikpapan operation that commenced on 1 July.[45] No. 14 Squadron had ceased its regular anti-submarine patrols on 23 May following the end of hostilities in Europe, but remained on standby in case any U-boats were found to be still active.[46] In July 1945, Brownell was appointed to command the newly formed No. 11 Group on Morotai; he handed Western Area over to his senior air staff officer, Group Captain Colin Hannah, who held temporary command for the remainder of the war.[47][48]

Post-war activity and disbandment

Following the end of the Pacific War in August 1945, SWPA was dissolved and RAAF Headquarters again assumed full control of all its operational formations, including the area commands.[49] Hannah handed over command of Western Area to Group Captain Douglas Wilson in October.[50] The RAAF shrank dramatically with demobilisation; wartime units were scheduled for dissolution in several stages, including reconnaissance-bomber squadrons by the end of 1945, and other bomber units by September 1946.[51] No. 14 Squadron was disbanded at Pearce in December 1945.[52] No. 25 Squadron's Liberators repatriated former prisoners of war from the Dutch East Indies to Australia until January 1946; the unit was disbanded in July that year.[53] Wilson was placed on the retired list in February 1946, and Hannah again assumed temporary command of Western Area until posted to Britain that October.[54][55] Group Captain Bill Garing took over as Officer Commanding Western Area the following month, by which time headquarters staff numbered 117, including thirty-one officers.[56]

In September 1946, the Chief of the Air Staff, Air Vice Marshal George Jones, proposed reducing the five extant mainland area commands (North-Western, North-Eastern, Eastern, Southern, and Western Areas) to three: Northern Area, covering Queensland and the Northern Territory; Eastern Area, covering New South Wales; and Southern Area, covering Western Australia, South Australia, Victoria and Tasmania. The Australian Government rejected the plan and the wartime area command boundaries essentially remained in place.[57][58] No. 25 Squadron re-formed as a Citizen Air Force unit at Pearce in April 1948, operating P-51 Mustangs and, later, de Havilland Vampire fighters.[59] As well as training reservists, the squadron was responsible for Western Australia's air defence.[60] Garing handed over command in November 1948; by the end of the month, Western Area headquarters staff numbered fourteen, including seven officers.[61]

Group Captain (later Air Commodore) Bill Hely took command of Western Area in October 1951.[62][63] During Operation Hurricane, the British atomic test in the Montebello Islands in October 1952, Hely coordinated air support including supply and observation flights by Dakotas of No. 86 (Transport) Wing.[64] He completed his term as AOC Western Area in September 1953, by which time headquarters staff numbered thirty-one, including fifteen officers.[65][66] Commencing the next month, the RAAF was reorganised from a geographically based command-and-control system into one based on function. In February 1954, the newly constituted functional organisations—Home, Training, and Maintenance Commands—assumed control of all operations, training and maintenance from Western Area Command.[2][67] Western Area remained in existence, but only as one of Home Command's "remote control points".[68] The headquarters was finally disbanded on 30 November 1956.[69]

Order of battle

As at 30 April 1942, Western Area's order of battle comprised:[23]

- RAAF Station Pearce

- No. 6 Fighter Sector Headquarters, Perth

Notes

- 1 2 Stephens, The Royal Australian Air Force, pp. 111–112

- 1 2 3 "Organising for war: The RAAF air campaigns in the Pacific". Pathfinder. No. 121. Air Power Development Centre. October 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- 1 2 Gillison, Royal Australian Air Force, pp. 91–92

- ↑ Gillison, Royal Australian Air Force, p. 92

- 1 2 Western Area Headquarters, Operations Record Book, p. 1

- ↑ Ashworth, How Not to Run an Air Force, pp. 28–29

- ↑ Ashworth, How Not to Run an Air Force, p. 294

- ↑ Western Area Headquarters, Operations Record Book, pp. 1–2

- ↑ RAAF Historical Section, Bomber Units, p. 43

- ↑ "No. 25 (City of Perth) Squadron". Royal Australian Air Force. Archived from the original on 3 January 2012. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- ↑ Wilson, The Eagle and the Albatross, pp. 72–73

- ↑ Gillison, Royal Australian Air Force, p. 112

- 1 2 Ashworth, How Not to Run an Air Force, pp. xx, 38

- ↑ Gillison, Royal Australian Air Force, p. 134

- ↑ RAAF Historical Section, Training Units, pp. 105–106

- ↑ Gillison, Royal Australian Air Force, p. 311

- ↑ Ashworth, How Not to Run an Air Force, pp. xxi, 134–135

- ↑ Ashworth, How Not to Run an Air Force, pp. 134–135

- ↑ Western Area Headquarters, Operations Record Book, p. 89

- ↑ Gillison, Royal Australian Air Force, p. 481

- ↑ Western Area Headquarters, Operations Record Book, p. 36

- ↑ Odgers, Mr Double Seven, p. 19

- 1 2 Ashworth, How Not to Run an Air Force, p. 299

- ↑ Western Area Headquarters, Operations Record Book, p. 68

- ↑ Gillison, Royal Australian Air Force, p. 473

- ↑ Odgers, Air War Against Japan, pp. 15–16

- ↑ Gillison, Royal Australian Air Force, p. 588

- ↑ Gillison, Royal Australian Air Force, pp. 585–588

- ↑ Odgers, Air War Against Japan, pp. 4–6

- ↑ Stephens, The Royal Australian Air Force, pp. 144–145

- ↑ RAAF Historical Section, Introduction, Bases, Supporting Organisations, p. 62

- ↑ Odgers, Air War Against Japan, p. 66

- ↑ Ashworth, How Not to Run an Air Force, pp. 302–304

- ↑ Western Area Headquarters, Operations Record Book, p. 187

- ↑ Odgers, Air War Against Japan, pp. 140–141

- ↑ Odgers, Air War Against Japan, p. 154

- ↑ Odgers, Air War Against Japan, pp. 136–139

- ↑ Odgers, Air War Against Japan, pp. 349–350

- ↑ Stevens, A Critical Vulnerability, pp. 264–265

- ↑ Western Area Headquarters, Operations Record Book, pp. 359–360

- ↑ Eather, Flying Squadrons of the Australian Defence Force, p. 63

- ↑ Stevens, A Critical Vulnerability, p. 279

- ↑ Waters, Oboe, pp. 18, 78, 135

- ↑ Odgers, Air War Against Japan, pp. 454–455

- ↑ Odgers, Air War Against Japan, pp. 475–476

- ↑ Odgers, Air War Against Japan, p. 353

- ↑ Ashworth, How Not to Run an Air Force, pp. 261, 304

- ↑ Western Area Headquarters, Operations Record Book, p. 478

- ↑ Ashworth, How Not to Run an Air Force, p. 262

- ↑ Western Area Headquarters, Operations Record Book, p. 496

- ↑ Stephens, Going Solo, pp. 11–12

- ↑ RAAF Historical Section, Bomber Units, p. 45

- ↑ RAAF Historical Section, Bomber Units, p. 83

- ↑ Western Area Headquarters, Operations Record Book, pp. 523, 531

- ↑ "For staff school". The West Australian. Perth: National Library of Australia. 25 October 1946. p. 8. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ↑ Western Area Headquarters, Operations Record Book, pp. 587, 593

- ↑ Helson, The Private Air Marshal, pp. 321–325

- ↑ Stephens, Going Solo, pp. 68, 462

- ↑ RAAF Historical Section, Bomber Units, pp. 82–83

- ↑ Eather, Flying Squadrons of the Australian Defence Force, pp. 63–64

- ↑ Western Area Headquarters, Operations Record Book, pp. 668–670

- ↑ "New air chief on citizen training". The West Australian. Perth: National Library of Australia. 24 September 1951. p. 2. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ↑ "Promotion in RAAF". The West Australian. Perth: National Library of Australia. 2 July 1952. p. 7. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ↑ "Atomic Weapon Tested". Benalla Ensign. Benalla, Victoria: National Library of Australia. 27 November 1952. p. 11. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ↑ "Changes in RAAF commands". The Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney: National Library of Australia. 2 September 1953. p. 2. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ↑ Western Area Headquarters, Operations Record Book, p. 774

- ↑ Stephens, Going Solo, pp. 73–76, 462–463

- ↑ "Battle 'nerve-centre' goes north: RAAF fighting control shifted from here". The Argus. Melbourne: National Library of Australia. 21 May 1954. p. 5. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ↑ "Order of Battle – Air Force – Headquarters". Department of Veterans' Affairs. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

References

- Ashworth, Norman (2000). How Not to Run an Air Force! Volume 1 – Narrative. Canberra: RAAF Air Power Studies Centre. ISBN 0-642-26550-X.

- Eather, Steve (1995). Flying Squadrons of the Australian Defence Force. Weston Creek, Australian Capital Territory: Aerospace Publications. ISBN 1-875671-15-3.

- Gillison, Douglas (1962). Australia in the War of 1939–1945: Series Three (Air) Volume I – Royal Australian Air Force 1939–1942. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 2000369.

- Helson, Peter (2010). The Private Air Marshal. Canberra: Air Power Development Centre. ISBN 978-1-920800-50-5.

- Odgers, George (1968) [1957]. Australia in the War of 1939–1945: Series Three (Air) Volume II – Air War Against Japan 1943–1945. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 246580191.

- Odgers, George (2008). Mr Double Seven: A Biography of Wing Commander Dick Cresswell, DFC. Tuggeranong, Australian Capital Territory: Air Power Development Centre. ISBN 978-1-920800-30-7.

- RAAF Historical Section (1995). Units of the Royal Australian Air Force: A Concise History. Volume 1: Introduction, Bases, Supporting Organisations. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. ISBN 0-644-42792-2.

- RAAF Historical Section (1995). Units of the Royal Australian Air Force: A Concise History. Volume 3: Bomber Units. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. ISBN 0-644-42795-7.

- RAAF Historical Section (1995). Units of the Royal Australian Air Force: A Concise History. Volume 8: Training Units. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. ISBN 0-644-42800-7.

- Stephens, Alan (1995). Going Solo: The Royal Australian Air Force 1946–1971. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. ISBN 0-644-42803-1.

- Stephens, Alan (2006) [2001]. The Royal Australian Air Force: A History. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-555541-4.

- Stevens, David (2005). A Critical Vulnerability: The Impact of the Submarine Threat on Australia's Maritime Defence 1915–1954. Canberra: Sea Power Centre – Australia. ISBN 0-642-29625-1.

- Waters, Gary (1995). Oboe: Air Operations Over Borneo 1945. Canberra: Air Power Studies Centre. ISBN 0-642-22590-7.

- Western Area Headquarters (1941–56). Operations Record Book. RAAF Unit History Sheets. Canberra: National Archives of Australia.

- Wilson, David (2003). The Eagle and the Albatross: Australian Aerial Maritime Operations 1921–1971 (Ph. D thesis). Sydney: University of New South Wales.