William Allen (Quaker)

| William Allen | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

29 August 1770 Spitalfields, London[1] |

| Died |

30 September 1843 (aged 73) Stoke Newington, London |

| Movement | abolitionist Quakers |

| Religion | Quaker |

William Allen FRS FLS FGS (29 August 1770 – 30 September 1843) was an English scientist and philanthropist who opposed slavery and engaged in schemes of social and penal improvement in early nineteenth-century England.

Early life

William Allen was the eldest son of devout Quakers Job and Margaret Allen. They were a well-to-do family, Job earning his wealth as a silk manufacturer. As a young man, in the 1790s, William Allen became interested in science. He attended meetings of various scientific societies, including lectures at St. Thomas's Hospital and Guy's Hospital, becoming a member of 'The Chemical Society' of the latter establishment.

In the first year of the new century, William Allen's father died, and the family silk business was thereafter managed by his father's assistant. This left William free to grow his own business in the field of pharmacy,[2] gradually becoming independent and establishing his own business. In 1802 he was elected a Fellow of the Linnean Society and lectured on chemistry at Guy's Hospital. A year later he was made president of the 'Physical Society' at Guy's, and on the advice of Humphry Davy and John Dalton also accepted an invitation from the Royal Institution to become one of its lecturers.

In 1807, Allen's original research (on carbon) enabled him to be successfully proposed for election to Fellowship of the Royal Society, bringing him into contact with those who were publishing much of the original scientific research of the day. This strengthened his ties with the eminent Humphry Davy, and in due course with his long-standing friend Luke Howard, who was likewise elected to Fellowship of the Royal Society, though some years later.

Pharmacy

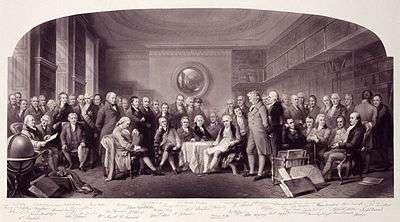

- ^ Engraving after 'Men of Science Living in 1807-8', John Gilbert engraved by George Zobel and William Walker, ref. NPG 1075a, National Portrait Gallery, London, accessed February 2010

- ^ Smith, HM (May 1941). "Eminent men of science living in 1807-8". J. Chem. Educ. 18 (5): 203. doi:10.1021/ed018p203.

William Allen was known in commerce for his pharmaceutical company Plough Court. Situated off Lombard Street in the heart of the City of London, and founded by the Quaker scientist Silvanus Bevan, it eventually grew into one of the UK's largest pharmaceutical companies: Allen & Hanburys. The company was acquired in 1958 by Glaxo Laboratories, who retained 'Allen and Hanburys' as a separate marque within the GSK group.

In 1841 William Allen co-founded The Pharmaceutical Society, which later became The Royal Pharmaceutical Society. He was its first president.

Allen's involvement with the Plough Court Pharmacy began in the 1790s when he began working there for Samuel Mildred. Already a thriving business in the City of London, with the arms of the Apothecaries Company emblazoned on its window, it continued to prosper and William Allen was offered a partnership; the company thereafter traded for a while under the name Mildred & Allen. Allen strengthened the company's links with medical institutions, particularly Guy's Hospital where he was elected to its Physical Society. Meanwhile, using Plough Court for meetings, he co-founded the Askesian Society. There new ideas for research and experimentation could be discussed with others such as Luke Howard, Joseph Fox, William Hasledine Pepys, William Babington, and the surgeon Astley Cooper. In 1797 Allen invited Luke Howard to formally collaborate with him at the Plough Court Pharmacy, the business then becoming known as Allen & Howard. A second laboratory was opened for the development of new chemicals, a few miles away in Plaistow.

Philanthropic and educational work

William Allen's philanthropic work was closely allied to his religious revivalist beliefs, and began at an early age. As the eighteenth century drew to a close, his concerns about the effects of a local famine, led to him opening a 'soup society'. Later his interest in agricultural experiments was also aimed improving the nutrition and diet of ordinary people susceptible to food shortages. Using only small plots, he carried out trials at Lordship Lane in Stoke Newington, and later put into practice some of his findings at the model agricultural settlement of Lindfield that he helped establish.

His self-sufficient settlement was described in detail in his pamphlet "Colonies at Home", where he stated "instead of encouraging emigration at enormous expense per head let the money be applied to the establishment of Colonies at Home and the increase of our national strength". To the people of the time (1820s) the known colonies were in the Americas so the whole area became known as "America". This identity remains in the local street names and people's memories of the cottages in what is now America Lane.[3]

William Allen's other philanthropic interest was education. He became greatly influenced by the ideas of Joseph Lancaster, who invented the monitorial system that bears his name. It was a cheap way of educating large numbers, where one teacher supervises several senior pupils who in turn instruct many junior ones. In 1808 Allen, Joseph Fox and Samuel Whitbread co-founded the Society for Promoting the Lancasterian System for the Education of the Poor, later the British and Foreign School Society for the Education of the Labouring and Manufacturing Classes of Society of Every Religious Persuasion. In 1810 William Allen became treasurer of the Society, whose aim was to open progressive schools in England and abroad. It was renamed the British and Foreign School Society in 1814, when Allen was again its treasurer.

In 1824 Allen founded the Newington Academy for Girls, also known as the Newington College for Girls, a Quaker school. Quaker views on women had from the beginning tended towards equality, with women allowed to minister, but still, at the time, girls' educational opportunities were limited. His school offered a wide range of subjects "on a plan in degree differing from any hitherto adopted", according to the prospectus. Here Allen was able to ensure that the new sciences were covered (he taught astronomy, physics, and chemistry himself[4]), as well as many languages. Allen hired Ugo Foscolo, a revolutionary and poet, to teach Italian. [5] The school was situated at Fleetwood House and made much use of Abney Park, the grounds in which it sat. It was also innovative in commissioning the world's first school bus, designed by George Shillibeer, to transport the pupils to Gracechurch Street meeting house on Sundays. The school was the subject of a poem by Joseph Pease, a railway pioneer who later became the first Quaker MP.

In 1811 William Allen, with the support of James Mill, started a publication entitled the Philanthropist. It published articles by Mill and by Jeremy Bentham. In 1816 he became a founding member of the Peace Society, a political development from his long-standing Quaker pacificism. From 1818 to 1820 he toured Europe with the Quaker evangelist Stephen Grellet.

Abolition of slavery

In 1805, after some years of assisting the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, William Allen was elected to its committee.

The society had always been strongly influenced by Quakers, and particularly by those based in or near London. All the members of its predecessor committee (1783–87) had been Quakers, and nine of the twelve founders of the subsequent non-denominational Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade were Quakers, including two - Samuel Hoare Jr and Joseph Woods Sr (father of the botanist Joseph Woods Jr) - who lived close to William Allen in Stoke Newington, the village near London where Allen had family interests after his second marriage in 1806.

Perhaps the best known committee member of the new non-denominational abolition society, founded in 1787, was William Wilberforce, who, unlike its Quaker members, was eligible as an Anglican to be elected to, and sit in, the House of Commons. Wilberforce visited William Allen at his experimental gardens on several occasions in his role as the Society's parliamentary representative. He had long been familiar with the village, owing to family connections. His sister Sarah had married the lawyer James Stephens, whose family home was the Summerhouse, a large house adjoining Abney Park in the very grounds of the mansion that later, in the 1820s, was to become William Allen's novel girls' school.

William Allen was also a founder member and a Director of the African Institution; the successor body to the Sierra Leone Company, sponsored by philanthropists to establish a colony in West Africa for slaves freed on a voluntary basis, through the abolitionists' efforts, in America. The work of the successor body began in 1808, when the colony had been handed to the Crown in return for the British Parliament passing legislation for its protection at about the same time as the passing in 1807 of the Act for the abolition of the slave trade.

William Allen's active interest in the abolitionist cause continued until his death. In the mid-1830s he was passionate about abolition of the apprenticeship clause, and achieving the complete freedom of African-Caribbean people on 1 August 1838. His biographer James Sherman records, 'the apprenticeship clause in the Bill... had been greatly abused by the planters. Mr Allen was indefatigable in his efforts, by interviews with Ministers and official persons.. His account of the spirit-stirring time is graphic:',

- The cruelty and oppression of the planters of Jamaica, as exercised on those poor sufferers, whose redemption from slavery we have paid twenty millions, has been exposed in the face of day. The West Indies in 1837, the result of personal investigation by our friend Joseph Sturge, has created a great sensation... The Anti Slavery Associations in all quarters are in a high degree of excitement, and petitions are loading the tables of both Houses of Parliament, begging for the abolition of the apprenticeship clause, and the complete establishment of freedom...on the 1st of Eight Month, 1838.

In 1839 William Allen became a founding Committee Member of the British and Foreign Anti-slavery Society for the Abolition of Slavery and the Slave-trade Throughout the World, which is today known as Anti-Slavery International. In this role he was an organiser of, and delegate to, the world's first anti-slavery convention, which was held in London in 1840 - an event depicted in a large painting by Benjamin Haydon that hangs in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Family life

William Allen married Mary Hamilton in 1796. They had a daughter, who bore the same name. Unfortunately, the mother did not recover from the childbirth, and died just two days later.

In 1806 Allen married for the second time. His new wife, Charlotte Hanbury of Stoke Newington, was the daughter of the wealthy Quakers Cornelius and Elizabeth Hanbury.[6] The marriage led to a long-standing association between Allen and her home village, a few miles north of London. The couple visited the continent in 1816, but Charlotte died during their travels, leaving him to bring up his adolescent daughter Mary. Tragedy struck again in 1823, when Mary (recently married to another Cornelius Hanbury) gave birth to a son but died just nine days later.

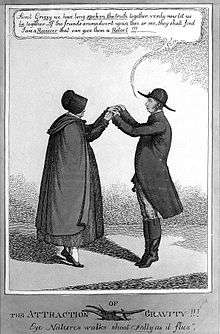

William Allen married for the third time in 1827. Grizell was the eldest sister of another family of well-off Stoke Newington Quakers, of whom the best-known is Samuel Hoare Jr (1751–1825), one of the twelve founding members of the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. She had stayed at home as nurse and companion to her father, a merchant in the City of London, and only married Wilson Birkbeck in 1801. As a wealthy widow, she contributed to the 1824 foundation of Newington Academy for Girls, and three years later she and William Allen, both co-founders of this novel educational establishment, married. She was 72, and their elderly marriage was greeted by a satirical cartoon entitled "Sweet William & Grizzell-or- Newington nunnery in an uproar!!!" by Robert Cruikshank[7] (brother of the more famous George).

This marriage was as tragic as his first two, for Allen's wife Grizell died in 1835, leaving him a widower for a third time. However, he had a large circle of friends, and was able to afford to travel extensively. In 1840, for example, he travelled for five months across Europe with Elizabeth Fry and Samuel Gurney.

Death and memorial

William Allen died on 30 September 1843 and was buried in Stoke Newington, London, in the grounds of the Yoakley Road Quaker Meeting House. Today this has been replaced by a Seventh Day Adventist chapel, the other half of its grounds becoming a small Council-maintained park for the nearby public housing estate.

Sources and further reading

- Sherman, Rev. James (1851 and reprinted). Memoir of William Allen, F.R.S. Charles Gilpin. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Claus Bernet (2007). "William Allen (Quaker)". In Bautz, Traugott. Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL) (in German). 28. Nordhausen: Bautz. cols. 20–24. ISBN 978-3-88309-413-7.

- Margaret, Nicolle (2001). William Allen: Quaker Friend of Lindfield (1770–1843). Quakers. Nicolle, Margaret. ISBN 0-9541301-0-3.

- Doncaster, Hugh (1965) 'Friends of Humanity: with special reference to the Quaker William Allen', London: Dr William's Trust

- Desmond Chapman-Huston (1954). Through a city archway: The story of Allen and Hanburys 1715–1954. J.Murray. ASIN B0000CIZI9.

- Shirren, Adam John (1951). The chronicles of Fleetwood House. A.J. Shirren, London. ASIN B0000CI4TT.

References

| Wikisource has the text of the 1885–1900 Dictionary of National Biography's article about William Allen. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to William Allen. |

- ↑ "William Allen". mdx.ac.uk. 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-21.

- ↑ "stoke newington quakers". stokenewingtonquakers. 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-21.

- ↑ rediscoveringamerica.org.uk

- ↑ Shirren, Fleetwood House p.160, cited in Quaker history page

- ↑ A P Baggs, Diane K Bolton and Patricia E C Croot, 'Stoke Newington: Education', in A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 8, Islington and Stoke Newington Parishes, ed. T F T Baker and C R Elrington (London, 1985), pp. 217-223. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/middx/vol8/pp217-223 [accessed 28 March 2016].

- ↑

Hanbury, Elizabeth (DNB12). Wikisource.

Hanbury, Elizabeth (DNB12). Wikisource. - ↑ British Museum collection