William Cooley

| William Cooley | |

|---|---|

New River Massacre | |

| Born |

1783 State of Maryland |

| Died |

1863 (aged 79–80) Hillsborough County, Florida |

| Occupation | Justice of the Peace, Politician, Farmer, Merchant, Soldier |

| Known for | Florida Pioneer |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Nancy Dayton (c. 1805–1836) |

| Children |

Almonock Cooley (c. 1827–1836) Montezuma Cooley (c. 1835–1836) Unnamed Daughter (c. 1825–1836) |

| Signature | |

|

| |

William Cooley (1783–1863) was one of the first American settlers, and a regional leader, in what is now known as Broward County, in the US state of Florida. His family was killed by Seminoles in 1836, during the Second Seminole War. The attack, known as the "New River Massacre", caused immediate abandonment of the area by whites.[1]

Cooley was born in Maryland, but little else is known about his life prior to 1813, when he arrived in East Florida as part of a military expedition. He established himself as a farmer in the northern part of the territory before moving south, where he traded with local Indians and continued to farm. He sided with natives in a land dispute against a merchant who had received a large grant from the King of Spain and was evicting the Indians from their lands. Unhappy with the actions of the Spanish, he moved to the New River area in 1826 to get as far as possible from the Spanish influence.[1]

In New River, Cooley sustained himself as a salvager and farmer, cultivating and milling arrowroot. His fortune and influence grew: he became the first lawman and judge in the settlement, besides being a land appraiser. Local Indians held him responsible for what they saw as a misjudgment involving the murder of one of their chiefs and attacked the settlement in revenge on January 4, 1836.[1]

Cooley survived the attack and lived for a further twenty-seven years. He held administrative positions in Dade County,[2] moved to Tampa in 1837, and had a short stint working for the U.S. Army as a guide and courier.[3] He moved to the Homosassa River area in 1840, where he became the first postmaster and was a Hernando County candidate for the Florida House of Representatives. Returning to Tampa in 1847, he was one of the first city councilors, serving three terms[4] before he died in 1863.[2][3][4]

Early life and arrival in East Florida

Cooley was born in Maryland in 1783;[1][5] little else is known about him prior to 1813. Cooley has been referred to as William Cooley Jr.,[6] William Coolie,[7] William Colee[8] and William Cooly.[8]

Cooley arrived in East Florida in 1813, during a joint campaign of Tennessee and Georgia forces. Some sources give credit to the hypothesis that Cooley fought with the Tennessee Volunteers under Colonel John Williams;[1][9] other sources say he was a lieutenant[10][11] in the Georgia Militia, fighting under Colonel Samuel Alexander[12] from Georgia.[13] Cooley acquired property in Girt's Landing on the St. Marys River,[1] close to where the military units crossed East Florida that same year.[14][15] Later, he went to the west bank of the St. Johns River, settling in an area 30 miles (48 km) south of modern Jacksonville.[1]

Cooley later moved to Alligator Pond (near present-day Lake City, Florida), where he set up a farm and traded with the local Seminole tribe led by Chief Micanopy.[1] The territory of East Florida was formally transferred from Spain to the United States in 1819, under the Adams-Onis Treaty. In 1820, Spanish merchant Don Fernando de la Maza Arredondo[16] began settlement of a 280,000-acre (1,130 km2) claim in the Alachua territory, which had been granted to him by King Ferdinand VII of Spain. Cooley negotiated with Don Fernando on behalf of the displaced Indians but was unsuccessful.[1] Cooley moved away in 1823[3]—possibly to escape the Spanish influence—to the north bank of the New River.[1]

New River settlement

Like the other New River settlers, Cooley did not buy land; he simply occupied the land in hope that the United States would eventually survey the area and grant ownership to the present settlers. The settlement was primarily populated by Bahamians, who survived by turtling, fishing, shipbuilding and wrecking.[1]

In 1830, Frankee Lewis, who in 1788 had been one of the area's first settlers,[17] sold her business interests to Richard Fitzpatrick. After Fitzpatrick's arrival, the settlement of approximately 70 people prospered with the introduction of a plantation regimen based on black slavery.[1]

Cooley's main occupation was gathering, processing and shipping arrowroot, a starch made from the root of the coontie plant. Arrowroot was used to make bread dough, wafers and biscuits; its resistance to spoilage made it especially favored for use on ships. Pulp remaining after processing was used as a fertilizer or for animal rations. Favorable conditions for arrowroot cultivation contributed to the presence of several hundred Indians in the area—arrowroot being a staple of their diet.[1] The market price for the starch was between 8¢ (US) and 16¢ per pound (between 17¢ and 35¢ per kg), and the geography of the river and the good performance of his machinery—the output was close to 450 lb (200 kg) per day—brought Cooley great prosperity. His good fortune allowed him to dedicate much of his time to exploration of the area as far north as Lake Okeechobee and brought him increasing political influence.[1] It is likely that he married Nancy Dayton, a former Indian captive, on December 2, 1830.[18][19] Richard Fitzpatrick, by that time the owner of a successful plantation with coconut and lime trees, plantains, and sugarcane, pressed for the appointment of Cooley as Justice of the Peace in 1831,[20] making Cooley responsible for adjudicating disputes of persons and property, punishment of minor offenders by fines and whippings, and oversight of the activities of wreckers. Serious offenders were jailed in Key West.[21] By that time, Cooley owned a schooner and took trips not only to take prisoners but to trade coontie, sugarcane, and tropical fruit with Cape Florida, Indian Key, Key West and Havana.[1]

While trade and farming activities were prominent, wrecking was the most important economic activity in the settlement. Northern newspapers started a campaign against wrecking in 1832, claiming that the activity was just a disguise for piracy; the 33 percent salvager's fee underscored their claim. Cooley, already in charge of overseeing wrecking, received a territorial appointment as appraiser of the sunk vessels and their cargoes. The strength of hurricane seasons affected the activity, and the especially active 1835 season brought even bigger profits.[1]

By 1835, Cooley had two sons and one daughter. The boys were named Almonock and Montezuma, after two local Indian chiefs. His ten-year-old daughter and his nine-year-old son were tutored by the couple Mary E. Rigby and Joseph Flinton.[1]

Cooley was appointed as an appraiser of property and slaves for Union Bank of Florida. His ally, Richard Fitzpatrick, purchased his coontie and citrus plantation on the Miami River for $2,500. Subsequently, Fitzpatrick was elected as representative for Monroe County to the Territorial Legislative Council. The unanimous vote for Fitzpatrick in New River was questioned by the Key West Inquirer. Cooley's conduct was implicitly questioned as well, since as Justice of the Peace, Cooley conducted the non-secret balloting. In Key West, Fitzpatrick lost to William Hackley.[1]

The Cooley property in New River had a house that was "twenty feet by fifty feet [6 by 15 m], one story high, built of cypress logs, sealed and floored with 1-1/2 inch [4 cm] planks".[1] At least three black slaves and several Indians cultivated sugar cane, corn, potatoes, pumpkins and other vegetables on the twenty-acre (eight-hectare) property, which also had a pen with eighty hogs. The coontie watermill was twenty-seven by fourteen feet (eight by four meters). His Key West holdings included a factory, two storage houses, kitchen and slave quarters; coconut, lime and orange trees; and domesticated and wild fowl.[1]

New River Massacre

Buildup

Cooley maintained friendly relations and trade with the Seminole Indians in the area. In the early nineteenth century, Creek Indians had moved from Alabama and joined the Seminoles. In 1835, white settlers killed Creek chief Alibama and burned his hut in a dispute. As Justice of the Peace, Cooley jailed the settlers, but they were released due to insufficient evidence after a hearing at the Monroe County Court in Key West. The Creek people blamed Cooley, saying he withheld evidence. The growing uneasiness between the Creeks and the whites led to the Creeks' emigration to the Okeechobee area.[1]

Major Francis L. Dade, military commandant at Key West, received intelligence that Cuba and Spain were arming the Indians; investigations did not confirm the rumor. Reports coming from Fort Brooke, near present-day Tampa, noted that Indians in the area were resisting orders from the federal government to emigrate to Mississippi, contradicting the assertions made by the federal authorities that the Indians had agreed to emigrate peacefully. Dade, two companies of soldiers, and all of the available arms were sent to Fort Brooke at Tampa Bay, the port designated for the commencement of the Indians' emigration. The Indians answered by concentrating all of their forces in the New River region.[1] On December 28, 1835, Dade and 107 soldiers were ambushed en route from Tampa Bay to Fort King, near present-day Ocala. Only three soldiers survived; the attackers lost only three men.[22]

Attack

Six days later, Cooley led a large expedition to free the Gil Blas, a ship that had beached the previous year. The scale of the operation required all of the settlement's able men. On the next day, January 4, 1836, the Indians attacked the settlement.[1]

Between fifteen and twenty Indians invaded the Cooley house, overpowering the tutor and scalping him. Cooley's wife grabbed their infant son and tried to run to the river, but was shot about 170 yards (155 m) from the house. The shot killed her and the baby. Cooley's nine-year-old son died from a fractured skull, and his daughter was shot. Two of Cooley's black slaves disappeared.[1][23]

The tutor's son heard the screams by the river and came back to retrieve his mother and two younger sisters. He managed to escape, going south by boat to the Cape Florida Lighthouse. Along the way, he warned the people at Arch Creek and Miami River of the attack, prompting them to flee as well.[1]

Aftermath

After the attack, the Indians torched the house and left without attacking other dwellings. The next day, Cooley came back to bury the dead; it is unclear who alerted the salvager's team to the attack.[1] After staying at the settlement for three days, Cooley went to the Cape Florida Lighthouse. One of the missing slaves appeared, reporting that he recognized the assailants as having been acquaintances of the Cooley family. The slave had heard the Indians ascribing the massacre to an act of revenge for Cooley's having failed to obtain the conviction of Chief Alibama's murderers.[1]

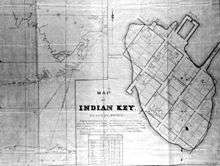

Cooley took charge of the lighthouse encampment. Richard Fitzpatrick sent sixty slaves from his Miami plantation to the lighthouse.[2] Fearing more attacks and aware of the precarious safety of the lighthouse, the settlers and slaves boarded Cooley's schooner and smaller boats and escaped to Indian Key, 100 miles (161 km) north of Key West.[2] Judge Marvin, a Key West justice, accused Seminole (or Calusa, depending on the source) chief Chakaika of leading the New River Settlement raiding group. This was not proved, but it is known that Chakaika was an important leader who coordinated the devastating attack on Indian Key in 1840.[24]

When Cooley arrived at Indian Key, he was informed that Indians had attempted to acquire arms and munition but had been repelled by the garrison in the island's fort. Meanwhile, more than two hundred people from nearby sought refuge in the fort. Cannons were salvaged from the Gil Blas;[2] the ship was later burned to deny the Indians a chance to recover anything from it.[25] Difficult sea conditions and fear of imminent attacks terrorized the islanders. Cooley asked for construction of forts at New River and Cape Sable, but news soon came from the Miami River reporting the total destruction of all white property, stalling all new initiatives.[2]

Cooley went back to New River and discovered the Indians had returned to loot the settlement and had burned several other houses and plantations. A claim for restitution of his losses was denied in 1840 by the United States House of Representatives.[26][27] Arriving at Key West on January 16, 1836, aboard the steamboat Champion, he was appointed temporary lighthouse keeper, staying until April of that year.[2]

After New River

Cooley resumed his life as a wrecker. Later that same year, he worked again as justice of the peace and assumed a position as a legislatively-appointed auctioneer.[2]

Constant attacks and rumor-spreading amplified the demands of Floridian community leaders, forcing the Navy to send Lieutenant Levin M. Powell to Key West. Lieutenant Powell built a small force of fifty seamen, ninety-five marines, and eight officers, reinforced by two schooners and the United States Cutter Washington, commanded by Captain Day. Powell called Cooley to be his guide in the enterprise because of his knowledge of Indian leaders and customs. Powell had mixed success, although by December 1836 the situation was under control at the coasts. Cooley went back to his usual duties in Indian Key (Dade County Seat); not long after, he moved to Tampa[2] but still worked occasionally as a guide.

General Thomas Jesup, headquartered in Fort Dade, made Cooley an express rider in early 1837 to deliver messages between Tampa Bay and Fort Heilman, a corridor of 170 miles (270 km).[3] That same year, reports circulated that Cooley was spreading rumors about a Seminole chief leading a rebellion involving black slaves and Indians. Afraid that Cooley could be directly involved, the general had him interrogated. Afterwards, a disgusted Cooley resigned his position.[2]

Politician

.png)

Cooley befriended Captain William Bunce, a retailer striving to keep Indians in the area, as they represented a source of cheap labor. He became involved again in local politics, this time against General Jesup, who wanted to remove all Indians from Florida. Judge Steele, a newcomer from Connecticut, was Cooley's ally in this fight.[2]

By 1840, he lived in Leon County, Florida, with a single slave.[28] Cooley was living near the Homosassa River,[29] where the Armed Occupation Act of 1842 allowed the distribution of 160-acre (65 ha) land grants. His leadership enabled him to get not only his own permit but permits for 28 other settlers. A lengthy correspondence with the General Land Office was eventually concluded satisfactorily for him and the other settlers.[30] In 1843, he was a candidate for a seat in the Florida House of Representatives for the newly created Hernando County, but he lost to James Gibbons. Two years later, he became the first postmaster in Homosassa[29] and County Commissioner of Fisheries.[31] He sold his land grant to Senator David Levy Yulee sequentially between 1846 and 1847 and moved back to Tampa.[32]

From 1848 to 1860, Cooley acquired several properties in the Tampa region,[32] including one at Worth's Harbor.[6] By 1850, he lived with seven slaves[33][34] and was a Captain of the "Silver Grays"—a militia for the home defense of Tampa in the 1850s.[35] He owned a general store in the city, eventually sold to a member of the Tampa Masonic Lodge.[36] He was nominated Port Warden of Tampa in 1853.[37] By 1855, Cooley had become a leader in local politics; he was the chairman at a meeting of the Democratic Party in Tampa, with sixty-five members enrolled, on August 4, 1855.[38] He was brought in as an alternate councilman for two months in the first Tampa council, served a full-year term beginning in February 1857, and returned in 1861 for another full term.[4] Cooley estimated his personal wealth at $10,060 in 1860.[39]

Death and legacy

Cooley died in 1863 in Hillsborough County, Florida. His will was written in 1862 but recorded only after Cooley's death, filed by Francis Matthews, who identified himself as his son-in-law.[40] In the document, Cooley is referred to as William Cooly. Cooley left his estate to friends, charities, a woman called Fanny Anne listed as his daughter (wife of Francis Matthews), and three grandsons and four granddaughters,[41][42] but there is no evidence that they were his blood relatives. Colee Hammock Park in Fort Lauderdale is located near the site of his old home in the New River Settlement.[8]

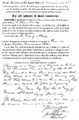

Cooley's Armed Occupation Act permit

Cooley's Armed Occupation Act permit- Letter to Florida Governor Thomas Brown, 1851

- Bill of Sale of a slave to Cooley, 1834

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 Cooper Kirk (March 1976). "William Cooley: A Broward Legend" (PDF). Broward Legacy. Broward County Historical Commission. 1 (1). Retrieved June 22, 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Cooper Kirk (March 1976). "William Cooley: A Broward Legend Part Two" (PDF). Broward Legacy. Broward County Historical Commission. 1 (2). Retrieved June 22, 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 Joe Knetsch (March 1989). "William Cooley explores the Everglades" (PDF). Broward Legacy. Broward County Historical Commission. 12 (2). Retrieved June 22, 2007.

- 1 2 3 "Archives, Tampa City Council Members February 1856 – June 1904". Retrieved June 22, 2007.

- ↑ Image:Cooley 1850 Census.jpg

- 1 2 J. Allison DeFoor, II (March 1986). "Odet Philippe in South Florida" (PDF). Tampa Bay History. 8 (1): 32. Retrieved June 22, 2007.

That Philippe was a contemporary of William Cooley, Jr., in the early settlement of New River is borne out by surviving records.

- ↑ Marjory Stoneman Douglas (1997) [1947]. "9". The Everglades: River of Grass. Pineapple Press. p. 216. ISBN 978-1-56164-135-2.

- 1 2 3 Gaines, Jim (April 25, 2002). "Fort Nowhere". New Times Broward-Palm Beach. Retrieved June 24, 2007.

- ↑ National Archives and Records Administration (1999). "Index to the Compiled Military Service Records for the Volunteer Soldiers Who Served During the War of 1812". War of 1812 Service Records. Provo, UT: Ancestry.com. M602.

Name:William Cooley; Company:2nd Regiment West Tennessee Militia; Rank – Induction:Private; Rank – Discharge:Private; Roll Box:45; Roll Exct:602

Although this is a good indicative, Colonel Williams was the leader of the Mounted Volunteers of East Tennessee; the 2nd Regiment West Tennessee Volunteer Mounted Gunmen was headed by Thomas Williamson. - ↑ Folks Huxford (1951). Pioneers of Wiregrass Georgia; a biographical account of some of the early settlers of that portion of Wiregrass Georgia embraced in the original counties of Irwin, Appling, Wayne, Camden, and Glynn. 1. Folks Huxford. pp. 116–117;188–189. The references put him alternatively building forts to protect the Telfair and Tattnall Counties in Georgia against Indians in 1813.

- ↑ Gordon, Julius J (1989). Biographical census of Hillsborough County, Florida, 1850 (PDF). J.J. Gordon. pp. 112–113. Retrieved July 10, 2007.

- ↑ "East Florida Papers-Col Samuel Alexander through Adjutant William Cooley". Retrieved June 24, 2007. Colonel Samuel Alexander was part of the same campaign, but from the Georgia counterpart. The units from Tennessee and Georgia met in East Florida.

- ↑ Samuel Alexander (May 8, 1813). "Letter enclosing a report, 1813 May 8, Twiggs County, (Georgia to) David B. Mitchell, Governor of Georgia, Milledgeville, Georgia – Samuel Alexander". Retrieved July 11, 2007.

- ↑ "A Comparative Timeline of General American History and Florida History, 1492 to 1823". Florida Humanities Council. Archived from the original on January 8, 2008. Retrieved July 11, 2007.

- ↑ "Brief History of TN in the War of 1812 – East Florida Campaign". Retrieved June 22, 2007.

- ↑ "Natural and Historic Sites in Alachua County". Archived from the original on June 18, 2007. Retrieved June 22, 2007.

- ↑ Broward County Historical Commission. "Broward Milestones". Archived from the original on April 27, 2007. Retrieved June 23, 2007.

- ↑ "Dodd, Jordan R, et al. Florida Marriages, 1822–1850 (database on-line). Provo, UT". Retrieved June 22, 2007.

WILLIAM COOLEY/NANCY DAYTON/2 Dec 1830/Monroe/FL

- ↑ Image:Cooley 1830 Census.jpg

- ↑ Carter, Clarence Edwin; John Porter Bloom; United States. Dept. of State. (1934). The Territorial papers of the United States (VOL XXIV) (1962 ed.). National Archives and Records Service. p. 485. OCLC 23262569.

confirmed as of May 29, 1831

- ↑ Carter, Clarence Edwin; John Porter Bloom; United States. Dept. of State. (1934). The Territorial papers of the United States (VOL XXIV) (1962 ed.). National Archives and Records Service. p. 417. OCLC 23262569.

- ↑ Bruce Vandervort (2006). "5". Indian Wars of Mexico, Canada and the United States, 1812–1900. Bruce Vandervort. pp. 132–134. ISBN 978-0-415-22472-7.

- ↑ "1" (PDF). A true and authentic account of the Indian war in Florida: giving the particulars respecting the murder of the Widow Robbins, and the providential escape of her daughter Aurelia, and her lover, Mr. Charles Somers, after suffering almost innumerable hardships. The whole compiled from the most authentic sources ... (PDF). New York: Saunders & Van Welt. 1836. pp. 10–11. Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- ↑ George E. Buker (January 1979). "The Mosquito Fleet's Guides and the Second Seminole War" (PDF). The Florida Historical Quarterly. Florida Historical Society. 57 (3): 311–326. Retrieved July 10, 2007.

- ↑ House of Representatives of the United States (June 30, 1856). "A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774–1875" (TIF). Bills and Resolutions, Senate, 34th Congress, 1st Session. 34: 355. Retrieved June 22, 2007.

- ↑ House of Representatives of the United States (May 19, 1840). "A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774–1875" (TIF). Journal of the House of Representatives of the United States. 34: 961. Retrieved June 22, 2007.

- ↑ House of Representatives of the United States (May 19, 1840). "A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774–1875" (TIF). Journal of the House of Representatives of the United States. 34: 1257. Retrieved June 22, 2007.

- ↑ Image:Cooley 1840 Census.jpg

- 1 2 "A Hernando County Timeline (to 1887)". Retrieved June 23, 2007.

- ↑ Joe Knetsch (March 1993). "William Cooley and the Land Office: A Note on Frontier Settlement" (PDF). Broward Legacy. Broward County Historical Commission. 16 (2). Retrieved June 22, 2007.

- ↑ Florida House of Representatives (December 27, 1845). "Journal of the Florida House of Representatives. 1845-11-17 – 1845-12-29": 238. Retrieved July 11, 2007.

- 1 2 "Land Patent Search, "Cooley, William" – Florida". Retrieved June 24, 2007.

- ↑ Image:Cooley 1850 Slave Schedule.jpg

- ↑ Image:Cooley 1850 Slave Schedule 2.jpg

- ↑ Joe Knetsch (June 1995). "John Darling, Indian Removal, and Internal Improvements in South Florida, 1848–1956" (PDF). Tampa Bay History. 17 (2). Retrieved June 24, 2007.

- ↑ Gordon, Julius J (1989). Biographical census of Hillsborough County, Florida, 1850 (PDF). J.J. Gordon. p. 448. Retrieved July 10, 2007.

- ↑ Florida House of Representatives (January 3, 1853). "Journal of the proceedings of the House of Representatives. 1852-11-22": 286. Retrieved July 11, 2007.

- ↑ "The Know-Nothings of Hillsborough County" (PDF). Retrieved June 22, 2007.

- ↑ Image:Cooley 1860 Census.jpg

- ↑ Image:Willian Cooley Preface Will.png

- ↑ Image:William Cooley Will.png

- ↑ Gordon, Julius J (1989). Biographical census of Hillsborough County, Florida, 1850 (PDF). J.J. Gordon. pp. 112–113. Retrieved July 10, 2007. Although this source says that the heirs lived in his house in 1850, this is not confirmed by the 1850 census, which says he is the only free man in his house. The assertion he had a wife called Christen is not confirmed, and neither is the affirmation that two of his daughters survived the attack in 1836. He did not die in 1860.

External links