Women in early radio

Women have been active participants in the development of radio (or wireless) communications since its beginning. The age of radio communication began with the development of wireless telegraphy around 1900, in which Morse code could be transmitted over large distances using simple spark gap or carbon arc transmitting equipment, and various types of detectors for reception. Guglielmo Marconi achieved international fame in 1901 when he succeeded in sending a simple message in Morse code - the letter "s" - across the Atlantic from Cornwall in England to Newfoundland.

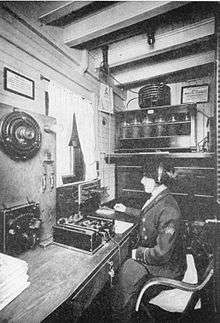

Women as Wireless Operators

Women had worked as telegraph operators since the late 1840s, and it was not long before women telegraphers began to work as wireless operators as well. In 1906, Anna Nevins, who had worked as a telegrapher for Western Union, began work as a wireless operator for Lee de Forest's station "NY", located at 42 Broadway in New York City. She was later employed as a wireless operator at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York City.[1]

Early Female Shipboard Operators

One of the earliest applications of wireless telegraphy was enabling communication between ships at sea and land stations. While early ships' operators were mostly male, some women entered the field as well. The primary requirement was a knowledge of Morse code and equipment operation, which many female telegraph operators possessed. Perhaps the earliest woman to operate on shipboard was Medora Olive Newell, an experienced telegrapher who was a passenger on the Cunard liner Slavonia in 1904, when Hungarian members of the Hague Peace Commission wished to send a birthday greeting to Emperor Franz Josef of Austria-Hungary. Medora Olive Newell (1872 - December 31, 1946) began work as a telegraph operator in Durango, Iowa, in 1886 at the age of fourteen. In 1897, she moved to Chicago and became a commercial operator for the Postal Telegraph Company.[2]

Newell’s first-class operator pay enabled her to live a fairly affluent lifestyle; as Telegraph Age reported in 1909, “Miss Newell has been in the habit of spending her vacations abroad, and has always made these trips the occasion for investigating telegraph and railway management and operation in European countries.”[3] On her return voyage from Europe in 1904, she found herself aboard the Cunard liner Slavonia together with members of the Hague Peace Commission, who were on their way to the United States to persuade President Theodore Roosevelt to call another international conference to continue the work begun at the Hague in 1899. The Hungarian members of the delegation wished to send a birthday greeting to Emperor Franz Josef of Austria-Hungary by wireless, but the ship’s wireless operator was unable to send the message. Newell, who, according to Telegraph Age, “had a good working knowledge of wireless,” took her place at the key and soon had successfully transmitted the greeting. The grateful delegates thanked her for her assistance, and the secretary of the Hungarian parliament invited her to visit Hungary as the guest of the nation.[4]

The Wireless Ship Act of 1910 required United States ships to be equipped with wireless equipment for the first time, and to have an operator on board who was capable of sending and receiving messages. The first woman to be officially employed as a shipboard wireless operator was Graynella Packer, a telegrapher from Jacksonville, Florida, who was employed as a wireless operator for the United Wireless Telegraph Company aboard the steamship Mohawk from November 1910 to April 1911.[5] From Jacksonville Florida,[6] Graynella Packer started practicing telegraphy in order to send messages in code to her school friends as a young girl. She eventually took on telegraphy as a career because her eyes were not strong and 'handling a key is no strain on the sight'.[7] She became manager of the Postal Telegraph office in Sanford, Florida, before hiring onto the Mohawk as the first woman wireless operator to serve aboard a steamship in a commercial capacity. After operating in full charge of the wireless, she eventually moved on to become an elected member of the Oklahoma State Bar Association from Oklahoma City in 1922.[8]

The Radio Act of 1912 required radio operators in the U.S. to be licensed for the first time. The first woman to be licensed as a shipboard operator was Mabelle Kelso, who passed the operator's examination and received her operating license in January 1912.[9] Mabelle Kelso was a native of Seattle, Washington, and had been previously employed as a stenographer. After passing a U.S. Navy Department examination, she was hired by the United Wireless Telegraph Company and assigned a position as an operator on board the SS Mariposa, a steamship which travelled between Seattle and Alaska. Her appointment as shipboard operator generated some opposition from members of Congress who wished to bar women from holding such positions on seagoing ships; however, she received support from the Pacific Coast Wireless Inspector of United Wireless, who stated that "he knew of no law which would bar Miss Kelso from her position."[10][11] By 1913, over 30 women had been licensed as shipboard operators.[12]

Women as Radio Amateurs

Amateur radio became a popular hobby in the early years of the twentieth century, and many hobbyists built their own transmitting and receiving equipment. Some of the earliest women radio amateurs, called "YLs," were Mrs. M.J. Glass of San Jose, California, who operated as station FNFN in 1910, and Olive Heartburg, who operated as station OHK in New York City in the same year.[13] M.S. Colville, of Bowmanville, Ontario, who began to operate as XDD in 1914, was one of the earliest Canadian YLs.[14]

The Radio Act of 1912 also required radio amateurs to be licensed. Gladys Kathleen Parkin (September 27, 1901 - August 3, 1990)[15] was one of the earliest women to obtain a government issued license. In 1916, while a fifteen-year-old high school student at the Dominican College in San Rafael, California, she obtained a first class commercial radio operators' license with the call sign 6SO.

Parkin was quoted in an article titled "The Feminine Wireless Amateur," which appeared in the October 1916 issue of The Electrical Experimenter:

"With reference to my ideas about the wireless profession as a vocation or worthwhile hobby for women, I think wireless telegraphy is a most fascinating study, and one which could very easily be taken up by girls, as it is a great deal more interesting than the telephone and telegraph work, in which so many girls are now employed. I am only fifteen, and I learned the code several years ago, by practising a few minutes each day on a buzzer. I studied a good deal and I found it quite easy to obtain my first grade commercial government license, last April. It seems to me that every one should at least know the code, as cases might easily arise of a ship in distress, where the operators might be incapacitated, and a knowledge of the code might be the means of saving the ship and the lives of the passengers. But the interest in wireless does not end in the knowledge of the code. You can gradually learn to make all your own instruments, as I have done with my 1/4 kilowatt set. There is always more ahead of you, as wireless telegraphy is still in its infancy."[16]

Use of the term "YL" to refer to female radio amateurs was formally adopted by the American Radio Relay League in 1920.

World War I and Women as Radio Operators

As the U.S. prepared to enter World War I, the Navy Department began a program to train women as radio operators who could be called into action in the event of war. The Girls' Division of the United States Junior Naval Reserve established training camps at the Martha Washington Post, in Edgewater, New Jersey, and the Betsy Ross Post, at Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, where young women were trained to become wireless operators.[17]

In January 1917, the National League for Women's Service (NLWS) was created from the Woman’s Department of the National Civic Federation readiness and relief activities and modelled on similar groups in Britain and elsewhere.[18][19] The League was divided into thirteen national divisions, one of which was "Wireless and Telegraphy".[20] When the US entered the war in April 1917, the NLWS established training program for female wireless operators at Hunter College in New York.[21][22] Although they were not strictly government employees, these female wireless operators were allowed to transmit in order to help the war effort.

Women as Broadcast Radio Engineers

By 1920, the technology had evolved to the point where voice and music could be transmitted as well as Morse telegraphy, and several radio stations began to broadcast regular programs of music and news. In 1920, Eunice Randall (1898-1982), an employee of The American Radio and Research Company, or AMRAD, became an engineer and announcer for the AMRAD radio station, 1XE. Her interest in radio had begun at the age of nineteen, when she built her own amateur radio equipment and operated with the call sign 1CDP. In addition to her technical duties at 1XE, which included repairing equipment and occasionally climbing the transmitting tower, she read stories for children as "The Story Lady," and gave the police report over the air.

In 1922, the AMRAD station changed its call sign to WGI. Eunice Randall remained as engineer and assistant chief announcer until 1925, when the company went bankrupt and the station was taken off the air. However, she continued to work as an engineer and draftsman, and resumed her amateur radio activities under the call sign of W1MPP.[23][24]

References

- ↑ Moreau, Louise R., "The Feminine Touch in Telecommunications." The A.W.A. Review, Volume 4, 1989, pp. 79-80.

- ↑ Obituary for Medora O. Newell, Long Beach Independent, Long Beach, CA, January 1, 1947.

- ↑ Telegraph Age, June 1, 1909, p. 396.

- ↑ Jepsen, My Sisters Telegraphic, p. 69.

- ↑ "The Feminine Wireless Amateur". The Electrical Experimenter, October 1916. pp. 396–7. Retrieved 2012-01-21.

- ↑ (October, 1916). The Feminine Wireless Amateur. Pages 396-397, 452. Publisher: The Electrical Experimenter

- ↑ (January 3, 1911). Girl Wireless Operator. Publisher: St. Petersburg (Florida) Evening Independent

- ↑ (1992)Proceedings of the Annual Meetings of the Oklahoma State Bar. Page 227. Publisher: Oklahoma State Bar Association

- ↑ Elizabeth, VE7TLK/VA7TK. "YL Amateur Radio Operators: "Their Struggles and Achievements"" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-02-05.

- ↑ "Miss Kelso of Seattle, Only Woman to Hold License as Wireless Operator," Atlanta Constitution, July 7, 1912.

- ↑ "May Flash Law On Wireless Girl," Oakland Tribune, Oakland, California, July 25, 1912.

- ↑ Moreau, "The Feminine Touch in Telecommunications," p. 80.

- ↑ Moreau, "The Feminine Touch in Telecommunications," p. 82.

- ↑ Elizabeth, VE7TLK/VA7TK. "YL Amateur Radio Operators: "Their Struggles and Achievements"" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-02-05.

- ↑ "California Death Index, 1940 - 1997". Ancestry.com. Retrieved 2012-01-27.

- ↑ "The Feminine Wireless Amateur". The Electrical Experimenter, October 1916. pp. 396–7. Retrieved 2012-01-21.

- ↑ "The Feminine Wireless Amateur". The Electrical Experimenter, October 1916. pp. 396–7. Retrieved 2012-01-21.

- ↑ Stevenson, Shanna. "National League for Woman's Service: Minute Women of Washington". Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ↑ "The National League of Women's Services". Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ↑ Clarke, Ida Clyde (1918). American Women and the World War. New York; London: D. Appleton and Company.

- ↑ "WOMEN GET INTO WIRELESS SERVICE; Hunter College to Graduate Two Girls Who Are Expert Operators.CLASS DOES MEN'S WORK 100 Students Taking the Course Will Be Qualified to AidIn War Work. Will Do Land Service. Appeal to Hunter College.". New York Times. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ↑ Thomas H. White. "United States Early Radio History". Retrieved 2012-02-17.

- ↑ Elizabeth, VE7TLK/VA7TK. "YL Amateur Radio Operators: "Their Struggles and Achievements"" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-02-05.

- ↑ Donna L. Halper. "Remembering the Ladies-- A Salute to the Women of Early Radio". Retrieved 2012-02-17.

Further reading

- Moreau, Louise R., "The Feminine Touch in Telecommunications." The AWA Review, Volume 4, 1989.

- Jepsen, Thomas C. (2000). My Sisters Telegraphic: Women in the Telegraph Office, 1846-1950. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press. ISBN 0-8214-1343-0.