Étienne Pierre Sylvestre Ricard

Étienne Pierre Sylvestre Ricard (31 December 1771 – 6 November 1843) was a prominent French division commander during the 1814 Campaign in Northeast France. In 1791 he joined an infantry regiment and spent several years in Corsica. Transferred to the Army of Italy in 1799, he became an aide-de-camp to Louis-Gabriel Suchet. He fought at Pozzolo in 1800. He became aide-de-camp to Marshal Nicolas Soult in 1805 and was at Austerlitz and Jena where his actions earned a promotion to general of brigade. From 1808 he functioned as Soult's chief of staff during the Peninsular War, serving at Corunna, Braga, First and Second Porto. During this time he sent a letter to Soult's generals asking them if the marshal should assume royal powers in Northern Portugal. When he found out, Napoleon was furious and he sidelined Ricard for two years.

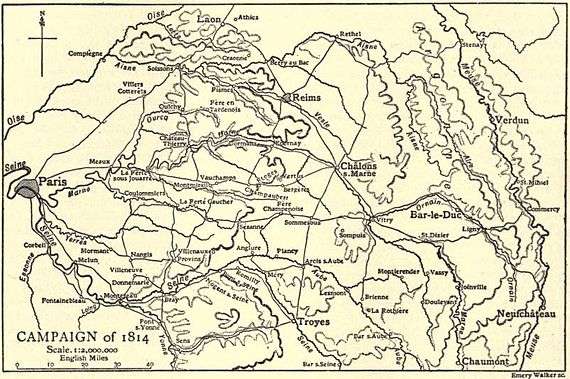

In 1811 Soult got Ricard reinstated and he fought at Tarragona. He participated in the 1812 French invasion of Russia, was promoted general of division and fought at Krasnoi. In 1813 he led a division in the III Corps at Lützen, Bautzen, Leipzig and Hanau, briefly leading the corps that winter. In 1814 he led a VI Corps division at La Rothière, Champaubert, Montmirail, Vauchamps, Gué-à-Tresmes, Laon, Reims, Fère-Champenoise and Paris. During the Hundred Days he went into exile with Louis XVIII, after which he was made a count by the restored king. He led troops in the 1823 French invasion of Spain. His surname is one of the names inscribed under the Arc de Triomphe, on Column 26.

Early career

Ricard was born on 31 December 1771 in Castres, France in what later became the Tarn department. In 1791 he joined the French Royal Army as a sous-lieutenant in the Le Fère Infantry Regiment. Within a year he was promoted to captain. He was soon transferred to Corsica for several years.[1] In 1799 he emerged as an aide-de-camp to Louis-Gabriel Suchet.[2] That year Suchet was made chief of staff to André Masséna in June and soon after chief of staff of the French Army of Italy under Barthélemy Catherine Joubert.[3] When Joubert was killed at the Battle of Novi, Suchet was at his side.[4] Suchet continued as chief of staff under Jean Étienne Championnet who lost the Battle of Genola on 4 November.[5] Championnet fell ill and died of fever on 9 January 1800.[6] Ricard's promotion to Adjutant General Chef de brigade came through on 31 December 1799.[7] Ricard fought at the Battle of Pozzolo in December 1800. After the war ended, he was given assignments in the 12th Military Division. Later he served at the Camp of Bruges before going to the Camp of Saint-Omer in 1803.[1]

Under Soult

In 1805 Ricard became aide-de-camp to Marshal Nicolas Soult and participated in the campaigns of the War of the Third Coalition.[1] In 1806 his noteworthy actions at the Battle of Jena in October earned him an elevation in rank to general of brigade.[2] The promotion came on 13 November 1806. This was followed by being awarded the Commander's Cross of the Légion d'Honneur on 7 July 1807 and being named a Baron of the Empire on 7 June 1808.[7] When Soult was sent to Spain to take command of the II Corps, Ricard was his chief of staff.[2]

After his long pursuit of a British army across northwest Spain, Soult was defeated at the Battle of Corunna on 16 January 1809. After the Royal Navy evacuated the British army,[8] Napoleon ordered Soult to invade northern Portugal and the marshal began his march south on 4 March.[9] In the Battle of Braga on 20 March, the French routed a large but poorly armed body of Portuguese militia, inflicting severe losses.[10] On 29 March, Soult's corps attacked the Portuguese defenders in the First Battle of Porto and the slaughter was even worse. The French easily broke through the Portuguese defenses and 7,000–8,000 Portuguese were killed or drowned in the massacre and stampede that followed.[11]

Before Braga, the French captured Chaves, where Soult proclaimed himself the viceroy of Portugal. Historian Charles Oman believed there was ample evidence that Soult's ambitions included crowning himself King of Northern Portugal. Since Napoleon appointed Marshal Joachim Murat the King of Naples in 1808, it did not seem so far fetched that a French general could become a monarch. There was a small pro-French faction which would have supported Soult's royal claim and the marshal did his best to curry favor with the local Portuguese leaders. In Oporto posters were put up on the walls declaring that Soult should be appointed king. One witness claimed that, for a week, Ricard threw coins to the crowds from the balcony of Soult's headquarters as they shouted, "Long live King Nicolas". On 19 April 1809, Soult directed Ricard to send a circular letter to his generals of brigades and divisions that encouraged them to cooperate with the program of making the marshal a king. The letter was careful to note that there would be no disloyalty to Napoleon if the movement was a success.[12]

The proceedings were interrupted when Arthur Wellesley, later known as Wellington appeared with a British army. On 12 May, Wellesley's army defeated Soult in the Second Battle of Porto and drove the French out of the city.[13] After a week-long retreat that included two hair-raising escapes, Soult's corps avoided destruction, though it lost 5,700 men killed or captured.[14] When Napoleon received a copy of Ricard's letter, he became enraged and wrote to Soult, harshly rebuking the marshal. The angry emperor pointed out that Soult had no right to assume royal powers without his permission. Napoleon ended by favorably recalling Soult's past battlefield performance, "I remember nothing but Austerlitz".[12] Ricard did not get off so easily and was recalled from Spain in disgrace.[2]

1811–1812

Ricard went into semi-retirement at Villefranche-de-Rouergue.[1] He was restored to favor when Soult asked for his services in 1811. He returned to Spain where he fought under Suchet's command at the Siege of Tarragona.[2] In the French invasion of Russia he served as a brigade commander in Charles Louis Dieudonné Grandjean's 7th Infantry Division which was part of Jacques MacDonald's X Corps. Beginning on 24 July 1812, MacDonald's command operated against Riga in the north. Ricard's brigade included two battalions of the 13th Bavarian Regiment and four battalions of the 5th Polish Regiment.[15] His troops occupied the Russian camp of Dünaburg in August.[1] He was promoted general of division on 10 September 1812.[7] Two months later he assumed command of the 2nd Infantry Division in I Corps and led the troops at the Battle of Krasnoi where he was wounded.[1] This action was fought on 14–18 November.[16]

1813

For the 1813 spring campaign, Ricard took command of the 11th Infantry Division in Marshal Michel Ney's III Corps. The 1st Brigade consisted of the 3rd and 4th Battalions of the 9th Light Infantry and two battalions each of the 17th and 18th Provisional Regiments. The 2nd brigade was made up of four battalions each of the 142nd and 144th Line Infantry.[17] There were 7,608 infantrymen, 175 gunners, 152 sappers and 305 wagon drivers. Both attached foot artillery companies were armed with six 6-pounders and two 5½-inch howitzers.[18] In the Battle of Lützen on 2 May 1813 the Russo-Prussian army achieved surprise when it attacked the III Corps. Joseph Souham's 8th and Jean-Baptiste Girard's 10th Divisions absorbed the force of the initial assault. Girard's artillery was not immediately available so the guns of Antoine François Brenier de Montmorand's 9th Division and Ricard's division were utilized in support.[19] Savage fighting revolved around four villages which were repeatedly taken and retaken. Ricard's troops recaptured the village of Kaja in the afternoon.[20]

In the Battle of Bautzen on 21 May 1813, the III Corps was ordered to envelop the Russo-Prussian right wing. The maneuver almost succeeded when Souham's division seized the key village of Preititz at 11:00 am, but then lost it to Allied counterattacks. At this time, Ney faltered, ordering his divisions to halt.[21] Three divisions, including Ricard's, recaptured Preititz at 3:00 pm. By this time, the Allied right wing succeeded in escaping Napoleon's intended trap.[22] Between 25 April and 31 May, the III Corps dwindled from 49,189 men to 24,581 men due to combat losses and sickness.[23] Though part of the III Corps was at the Battle of Katzbach on 26 August, Ricard's division was not engaged.[24]

Ricard's division fought at the Battle of Leipzig on 16–19 October 1813 with a strength of 4,357 men and 12 guns.[25] On the 16th, Napoleon intended for the III Corps, now led by Souham, to aid his attack to the south of Leipzig. However, when fighting unexpectedly broke out to the north of the city, Ney held the corps back then later changed his mind. Consequently, Napoleon launched his main assault without III Corps, and it was only in the evening that Ricard's division belatedly intervened on the southern front.[26] The division participated in the Battle of Hanau on 30–31 October.[27] Subsequently, Napoleon's wrecked army retreated across the Rhine River. The III Corps, now led by Ricard, was at Höchst on 1 November. Crossing the Rhine on 3 November, the III Corps took position at Bechtheim.[28]

1814

On 30 December 1813, Ricard commanded the 3,000-man 1st Division in Marshal Auguste Marmont's VI Corps. That day his troops left Koblenz and moved south, to be replaced by Pierre François Joseph Durutte's division. During this transfer, the Allies launched a successful crossing of the Rhine on 1 January 1814 and threatened to capture the isolated French.[29] By hard marching, Ricard and Durutte managed to elude the Allies and reach Saarbrücken.[30] On 14 January, believing he was about to be surrounded, Ricard evacuated Pont-à-Mousson without orders. His worst mistake was not destroying the bridge over the Moselle River. The French forces withdrew toward the Meuse River. [31] On 19 January Ricard's rear guard ambushed some Prussian cavalry in a brisk skirmish at Manheulles.[32]

When Napoleon arrived at the front on 26 January 1814, Marmont's 12,051-man command included Jean-Pierre Doumerc's I Cavalry Corps and the VI Corps with the divisions of Ricard and Joseph Lagrange.[33] Hoping to surprise Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher's army, Napoleon launched an advance in three columns. The right column led by Étienne Maurice Gérard consisted of the divisions of Ricard and Georges Joseph Dufour. Marmont guarded the army's rear with Lagrange's division.[34] On 1 February the Allies with 120,000 troops defeated Napoleon with 45,000 at the Battle of La Rothière.[35] Only 85,000 Allies came into action. Gérard's ad hoc corps held Dienville on the right flank with 8,300 men. Their opponents were the Austrian III Corps under Ignaz Gyulai with one division on the west bank of the Aube River and the brigade of Franz Splény de Milháldy on the east bank. The west bank division briefly captured Dienville's bridge before being thrown back. The Austrians only took Dienville at midnight after Gérard abandoned the village. Both sides suffered about 6,000 casualties in the battle, but Napoleon lost 60 field pieces and was forced to retreat. [36] A battle map showed Dufour in the first line and Ricard in the second line.[37] A Russian attempt to cut off the French retreat the next day was blocked by Emmanuel Grouchy's cavalry and Ricard at Piney.[38]

Napoleon with 30,000 troops pounced on Blücher's widely separated army in the Six Days' Campaign.[39] On 10 February, the French attacked Nicolay Dmitrevich Olssufiev's 4,000 Russian infantry and 24 guns. Stung by recent criticism, Olssufiev unwisely stood his ground against overwhelming odds in the Battle of Champaubert. About 11:00 am Marmont's corps began the assault with the divisions of Ricard on the right against Baye and Lagrange on the left against Bannay. Despite stout resistance, the villages were seized by 3:00 pm and French cavalry was advancing on both flanks. Belatedly Olssufiev ordered a retreat but 1,000 men and nine guns were surrounded at Champaubert and forced to surrender. At most, 1,700 Russians escaped through the woods east to Étoges and Olssufiev became a French prisoner.[40] There were 38,000 Allies under Fabian Wilhelm von Osten-Sacken and Ludwig Yorck von Wartenburg to the west and Blücher's 19,000 to the east.[41]

In the Battle of Montmirail on 11 February, Napoleon moved against Sacken's 18,000 Russians and 90 guns west of Montmirail with Ricard's division and some cavalry. After being driven out of Marchais at 11:00 am, Ricard's division was ordered to recapture the village. After a furious struggle that raged until 2:00 pm, Marchais remained in Russian hands. By this time Ney's corps arrived to put more pressure on the Russians. The French finally captured Marchais and most of its defenders were cut down by French cavalry as they fled. Escaping to the north with difficulty, Sacken lost 2,800 men, six colors and 13 guns while Yorck's Prussians sustained 900 casualties. The French lost 2,000 killed and wounded.[42] At Montmirail Ricard's division consisted of the one battalion each of the 2nd, 4th, 6th, 9th and 16th Light Infantry and the 22nd, 40th, 50th, 65th, 136th, 138th, 142nd, 144th and 145th Line Infantry.[43]

Ricard missed the Battle of Château-Thierry on the 12th. The Battle of Vauchamps was fought on 14 February 1814 between Napoleon and Blücher.[44] As Hans Ernst Karl, Graf von Zieten's 5,700-strong Prussian vanguard emerged from Vauchamps, it found it was facing Marmont's 5,000-man corps. By this time, Ricard's division had shrunk to a strength of 800 men. Nevertheless, Marmont ordered it forward and Ricard's men were driven back. When the Prussians pursued, they were met by Lagrange's infantry in front and Grouchy's cavalry charging in from the right. Zieten's division was nearly destroyed with very heavy losses. By the end of the day Napoleon had badly beaten Blücher who lost 4,000 Prussians, 2,000 Russians and 16 guns. The French counted only 600 casualties.[45]

Ricard's next action was the Battle of Gué-à-Tresmes on 28 February 1814 in which the French defeated Friedrich Graf Kleist von Nollendorf's Prussian II Corps. The 14,500 French under Marmont inflicted 1,035 casualties on the 12,000 Prussians while sustaining losses of 250. At this time Ricard's division numbered 790 light and 2,000 line infantry.[46] The Battle of Laon was fought on 9–10 March and resulted in Napoleon's defeat.[47] On the evening of the 9th, Marmont's corps was surprised by the Prussians and routed, suffering a loss of 3,500 casualties, 45 guns and most of its wagons.[48] Napoleon mauled an Allied corps in the Battle of Reims on 13 March, capturing 22 field pieces. Casualties numbered 900 French, 1,400 Russians and 1,300 Prussians.[49] The Russian commander Emmanuel de Saint-Priest with 14,500 men did not know Napoleon was present with 20,000 troops and took up a bad position outside Reims. The French attack was led by two cavalry divisions followed by Ricard's infantry. Saint-Priest was fatally wounded by a cannon shot and his troops chased from the city.[50]

In the Battle of Fère-Champenoise on 25 March 1814, Marmont and Édouard Mortier, duc de Trévise with 17,000 foot, 4,000 horse and 84 guns were defeated by 28,000 Allies, most of whom were cavalry, and 80 guns.[51] The French cavalry were overwhelmed, leaving the infantry to be hustled from Soudé to Fère-Champenoise by the Allied horsemen. French losses numbered 2,000 killed and wounded plus 4,000 men, 45 guns and 100 caissons captured.[52] The Battle of Paris was fought on 30 March by which time Ricard's division numbered only 726 men.[53] The 107,000 Allies defeated the 42,000 French defenders who abandoned the capital that evening.[54] In consequence, Napoleon abdicated his throne on 6 April.[55]

Later career

Under King Louis XVIII, Ricard was awarded the knight's cross of the Order of Saint Louis and given command of the 10th Military District at Toulouse. In 1815 he was sent to the Congress of Vienna to convince the Allies that France's army was loyal to Louis XVIII. This mission was rendered moot when Napoleon overthrew the Bourbons during the Hundred Days and Ricard traveled to Ghent to join the king in exile.[1] In 1817 Ricard was ennobled as a count. In the 1823 French invasion of Spain he served as a division commander in Jacques Lauriston's corps. He led the Royal Guard infantry division from 1829 to 1831, when he retired from the army.[56] He died on 6 November 1843 at Recoules, Aveyron, France. RICARD is inscribed on the south side of the Arc de Triomphe.[1]

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Jensen 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Chandler 1979, p. 378.

- ↑ Phipps 2011, p. 104.

- ↑ Phipps 2011, p. 331.

- ↑ Phipps 2011, pp. 338–341.

- ↑ Phipps 2011, pp. 347–348.

- 1 2 3 Broughton 2007.

- ↑ Chandler 1979, pp. 107–109.

- ↑ Oman 1995, p. 192.

- ↑ Oman 1995, pp. 233–237.

- ↑ Oman 1995, pp. 244–249.

- 1 2 Oman 1995, pp. 273–277.

- ↑ Chandler 1979, p. 320.

- ↑ Oman 1995, pp. 341–361.

- ↑ Smith 1998, p. 408.

- ↑ Smith 1998, p. 403.

- ↑ Smith 1998, p. 417.

- ↑ Nafziger 1992.

- ↑ Leggiere 2015, pp. 231–235.

- ↑ Leggiere 2015, pp. 238–239.

- ↑ Leggiere 2015, pp. 345–347.

- ↑ Leggiere 2015, pp. 354–355.

- ↑ Leggiere 2015, p. 422.

- ↑ Smith 1998, p. 442.

- ↑ Smith 1998, p. 463.

- ↑ Chandler 1966, pp. 929–931.

- ↑ Smith 1998, p. 474.

- ↑ Leggiere 2007, pp. 63–65.

- ↑ Leggiere 2007, pp. 231–238.

- ↑ Leggiere 2007, p. 245.

- ↑ Leggiere 2007, p. 374.

- ↑ Leggiere 2007, pp. 459–460.

- ↑ Petre 1994, p. 17.

- ↑ Petre 1994, p. 19.

- ↑ Smith 1998, pp. 491–492.

- ↑ Petre 1994, pp. 30–37.

- ↑ Petre 1994, p. Map IId.

- ↑ Petre 1994, p. 42.

- ↑ Petre 1994, p. 53.

- ↑ Petre 1994, pp. 58–60.

- ↑ Petre 1994, p. 57.

- ↑ Petre 1994, pp. 63–65.

- ↑ Smith 1998, p. 495.

- ↑ Smith 1998, p. 496.

- ↑ Petre 1994, pp. 68–71.

- ↑ Smith 1998, p. 505.

- ↑ Smith 1998, p. 510.

- ↑ Petre 1994, pp. 141–142.

- ↑ Smith 1998, p. 511.

- ↑ Petre 1994, pp. 149–150.

- ↑ Smith 1998, p. 514.

- ↑ Petre 1994, pp. 190–191.

- ↑ Smith 1998, p. 515.

- ↑ Petre 1994, pp. 199–200.

- ↑ Smith 1998, p. 517.

- ↑ Chandler 1979, p. 379.

References

- Broughton, Tony (2007). "Generals Who Served in the French Army during the Period 1789-1815: Rheinwald to Ruty". The Napoleon Series. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- Chandler, David G. (1966). The Campaigns of Napoleon. New York, N.Y.: Macmillan.

- Chandler, David G. (1979). Dictionary of the Napoleonic Wars. New York, N.Y.: Macmillan. ISBN 0-02-523670-9.

- Jensen, Nathan D. (2014). "Etienne-Pierre-Sylvestre Ricard". FrenchEmpire.net. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- Leggiere, Michael V. (2007). The Fall of Napoleon: The Allied Invasion of France 1813-1814. 1. New York, N.Y.: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87542-4.

- Leggiere, Michael V. (2015). Napoleon and the Struggle for Germany: The Franco-Prussian War of 1813. 1. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-08051-5.

- Nafziger, George (1992). "French Order of Battle, Lützen or Gross-Görschen, 2 May 1813" (PDF). United States Army Combined Arms Center. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- Oman, Charles (1995) [1903]. A History of the Peninsular War Volume II. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole. ISBN 1-85367-215-7.

- Petre, F. Loraine (1994) [1914]. Napoleon at Bay: 1814. London: Lionel Leventhal Ltd. ISBN 1-85367-163-0.

- Phipps, Ramsay Weston (2011) [1939]. The Armies of the First French Republic: Volume V The Armies Of The Rhine In Switzerland, Holland, Italy, Egypt, and The Coup D'Etat of Brumaire (1797-1799). 5. USA: Pickle Partners Publishing. ISBN 978-1-908692-28-3.

- Smith, Digby (1998). The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill. ISBN 1-85367-276-9.