1955 24 Hours of Le Mans

| 1955 24 Hours of Le Mans | |

| Previous: 1954 | Next: 1956 |

| Index: Races | Winners | |

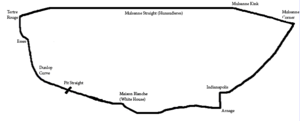

The Les 24 Heures du Mans was the 23rd 24 Hours of Le Mans, and took place on 11 and 12 June 1955 on Circuit de la Sarthe. It was also the fourth round of the F.I.A. World Sports Car Championship. Some 250,000 spectators had gathered for Europe’s classic sports car race, around an 8.38-mile course. This race is infamous for the disaster that killed 84 people, plus some 120 injured in the most horrendous accident in motor racing history.

Report

Entry

A grand total 87 racing cars were registered for this event, of which only 70 arrived for practice, trying to qualify for the 60 places for the race. The battle of the previous years between Coventry and Maranello concerns was joined by the Stuttgart marque, Daimler-Benz, fresh from their triumph on the Mille Miglia with their new Mercedes-Benz 300SLR. Scuderia Ferrari’s hope were in the hands of Umberto Maglioli and Phil Hill, Eugenio Castellotti and Paolo Marzotto, and Maurice Trintignant and Harry Schell driving the new 121 LM. Jaguar arrived with three works Jaguar D-Types. Similar to the cars that raced in 1954, they were in the hands of Mike Hawthorn and Ivor Bueb, the 1953 winners, Tony Rolt and Duncan Hamilton and Don Beauman and Norman Dewis. They were backed up by a pair of D-Types from the Belgian team, Ecurie Francorchamps, and from the American, Briggs Cunningham team. Cunningham also brought over to Europe, a Cunningham C6-R.[1][2]

Meanwhile, Daimler-Benz assembled an all-star team for the race, pairing Juan Manuel Fangio with Stirling Moss, Karl Kling with André Simon and Pierre Levegh with John Fitch. Simon and Levegh were not regular members of the Mercedes team, but team manager Alfred Neubauer felt it would be popular, even diplomatic, to include two local drivers. Remember, World War II ended only ten years previously, and in the 1952 race, driving solo, Levegh almost won the race, until the 23rd hour when mechanical trouble sidelined him, handing the win to Mercedes.[1][3][4] Their cars, designated W196S although they were commonly called 300SLRs, were rated by many experts as the best sports cars in the world. They were an adaptation of the systems that had brought them dominance in Grand Prix racing to sports endurance racing. Their fuel-injected, desmodronic valve 3 liter straight eight motors were the most advanced of the entire field. Their inboard drum brakes, however, were questionably adequate for their heavier cars facing the tough braking and endurance demands of Le Mans. To compensate, a hand-operated air brake was added to the rear deck for high speed braking.

Race

The earliest hours of the race fulfilled the expectations of a showdown between the three top marques. Castellotti's Ferrari led from the first lap, followed by Hawthorn in the Jaguar. Fangio's start was delayed by a mishap between his trouser leg and gear shift lever, but he worked his way up the field to join Hawthorn and Castellotti. All three were breaking track records. As the race wore on, Castellotti's pace slowed and he was overtaken by Hawthorn and Fangio. It was an early sign of the mechanical troubles that would force all of the 121 LMs to retire within twelve hours. What followed was one of the classic duels in auto racing history, with multiple lead changes between Hawthorn and Fangio and a record-setting pace.

Two hours into the race, a dreadful accident occurred on lap 35. Hawthorn passed Lance Macklin's Austin-Healey 100S while entering the final straight before the pits. Seeing the Jaguar crew signaling him for a pit stop, Hawthorn moved across Macklin's path and braked hard to enter the pits.[5][6][7][8] Attempting to avoid Hawthorn, Macklin's car briefly remained on the right side of the track behind Hawthorn, kicking up dust with its right wheels, then swerved across the center of the track. Macklin was apparently out of control as he started to swerve, but regained direction after crossing the centerline. But by then Macklin was in the path of Levegh's Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR and the right front wheel of Levegh's car rode up onto the left rear corner of Macklin's, which caused the 300 SLR to become airborne. The photos and video stills illustrate the thin margin – a fender width – between a near miss and complete disaster.

Levegh's car skipped on the earthen embankment between the spectator area and the track, bounced and flipped end-over end through spectator enclosures, then struck a concrete stairwell structure. That impact disintegrated the front end and pitched the car high, somersaulting and hurling debris into the crowd. The front bodywork plowed directly into the crowd. The front suspension, engine, and other debris flew through the spectator area leaving swaths of destruction in front of the grandstands. The remainder of the car landed on the earthen embankment and exploded into flames. Spectators who had climbed onto ladders and scaffolding to get a better view of the track found themselves in the direct path of the lethal debris. Levegh was thrown in a high arc from the tumbling car, and his skull was crushed at some point. When firefighters attempted to douse the flames with water, the fire burned even hotter owing to the resultant chemical reaction with the magnesium alloy frame. Officials put the death toll at 84 spectators, plus Levegh.[3][4][9][10] Macklin's car ricocheted off the pit wall back to the earthen embankment. He was uninjured but his car struck three people, killing one. Fangio dodged between Macklin's and Hawthorn's cars and continued on. Hawthorn was waved through his stop because of the confusion and potential danger.

Ten minutes later, the MG EX182 of Dick Jacobs crashed near Maison Blanche, turned over in the swale and began to burn. Jacobs survived the accident, but was badly injured.

With the driver changes from Hawthorn to Bueb and Fangio to Moss, the Jaguar team's talent was outmatched and the Mercedes team was able to expand the lead it had gained following the accident. As midnight approached, the Mercedes of Fangio/Moss was leading the Jaguar of Hawthorn/Bueb by nearly two laps. The race remained competitive, however, as the lead was whittled to 1 1/2 laps by 2:00am.[11] The Kling/Simon Mercedes followed the Hawthorn/Bueb car by two laps. Race spotters' reports on the Mercedes' braking points led the Jaguar team to believe that their brakes were weakening.[12]

Just after 2:00am, Mercedes team manager Alfred Neubauer stepped onto the track and called his cars into the pits. The public address made a brief announcement regarding their retirement. Chief engineer Rudolf Uhlenhaut then went to the Jaguar pits to ask if the Jaguar team would respond in kind, out of respect for the accident's victims. Jaguar team manager "Lofty" England declined.[12]

With the Mercedes team ordered home, the lead fell securely to Hawthorn and Bueb. Dawn broke under a heavy low overcast and by 6:00am it started to rain. Second place remained in contention until late morning as the Valenzano/Musso Maserati, five laps down from the leader, was chased by the Frere/Collins Aston Martin until the Maserati retired. Bueb, in his first event for the Coventry marque, surrendered the winning Jaguar in the final hour to Hawthorn for the final few laps.

Hawthorn and Bueb covered a distance of 2,569.61 miles (4,135.38 km), over 306 laps, averaging a speed of 107.067 mph (172.308kph). Peter Collins and Paul Frère, in second place in their Aston Martin DB3S were five laps behind at the finish. The podium was completed by the Belgian pair, Johnny Claes and Jacques Swaters, in their yellow Ecurie Francorchamps prepared Jaguar D-Type, who were 11 laps (over 92 miles) behind the winners. The remarkable trio of 1.5 liter Porsche 550 Spyders were fourth, fifth and sixth, ahead of the two liter Bristols, with Helmut Polensky and Richard von Frankenberg winning the Sports 1500 class. The three-car Bristol Aeroplane Company team finished in formation seventh, eighth and ninth at the top of two-liter class.[2]<[13]

Aftermath

The spectacular crash, which came to be known as the 1955 Le Mans disaster, is the greatest tragedy in the history of motorsport, with 84 spectators killed and over 120 injured. The next round of the World Sports Car Championship at the Nürburgring was cancelled, as was the legendary Carrera Panamericana. The accident caused widespread shock and temporary bans on auto racing in several countries. The ban in Switzerland was never lifted. The American Automobile Association stopped sanctioning motor sport competitions, as it decided that auto racing distracted from its primary goals, and the United States Automobile Club was formed to take over the race sanctioning/officiating.[3][4] The racing teams of MG, Bristol, and (after winning the 1955 Grand Prix and Sports Car championships), Mercedes-Benz, disbanded. The horror of the accident caused some drivers present, including Phil Walters, Sherwood Johnston, and John Fitch (after completing the season with Mercedes-Benz), to retire from racing. Fitch was coaxed out of retirement by his friend Briggs Cunningham to help the Chevrolet Corvette effort at Le Mans in 1960 and later worked to develop traffic safety devices including the water-filled "Fitch barrels." Less than three months later, Lance Macklin decided to retire after being involved in a twin fatality accident during the Tourist Trophy race at Dundrod.

Much recrimination was directed at Hawthorn based on rumors that he had suddenly cut in front of Macklin and slammed on the brakes near the entrance to the pits, forcing Macklin to take evasive action into the path of Levegh, which became the semi-official pronouncement of the Mercedes team and Macklin's story.[12] The Jaguar team in turn questioned the fitness and competence of Macklin and Levegh. The first media accounts were wildly inaccurate, as shown by subsequent analysis of photographic evidence conducted by Road & Track editor (and 1955 second-place finisher) Paul Frere, in 1975.[12] Additional details emerged when the stills reviewed by Frere were converted to video form. The Automobile Club l'Ouest (ACO) conducted an investigation and concluded that the primary cause of the accident was unsafe conditions near the entrance to the pit straight. Tony Rolt and other drivers had been raising alarms about the pit straight since 1953.

Before the 1956 event, the ACO widened the pit straight, increased separation between the road and the spectators, and revised other hazardous stretches of the track. Track safety technology and practices evolved slowly until Formula 1 driver Jackie Stewart organized a campaign to advocate for better safety measures 10 years later. Stewart's campaign gained momentum after the deaths of Lorenzo Bandini and Jimmy Clark.

Official Classification

Class Winners are in Bold text.

Did not finish

Did not start

| Pos | Class | No | Team | Drivers | Chassis | Engine | Reason |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNS | S 5.0 |

2 | |

|

Talbot Lago Sport | Talbot 4.5L L6 | |

| DNS | S 3.0 |

17 | |

|

Gordini T24S | Gordini 3.0L L8 | Accident in practice |

| DNS | S 1.1 |

45 | |

|

Arnott Sports | Coventry Climax 1.1L L4 | Accident |

| DNS | S 750 |

54 | |

|

Moretti 750S | Moretti 0.7L L4 | Gridded too late |

| DNS | S 750 |

55 | |

|

Moretti 750S | Moretti 0.7L L4 | Gridded too late |

| DNS | S 750 |

70 | |

|

Ferry F750 | Renault 0.7L L4 | Reserve |

| DNS | S 750 |

72 | |

|

V.P. 155R | Renault 0.7L L4 | Reserve |

| DNS | S 750 |

75 | |

|

Renault 4CV/1063 | Renault 0.7L L4 | Reserve |

- Fastest Lap: Mike Hawthorn, 4:06.6secs (122.388 mph) [13]

Class Winners

| Class | Winners | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sports 5000 | 6 | Jaguar D-Type | Hawthorn / Bueb |

| Sports 3000 | 23 | Aston Martin DB3S | Collins / Frère |

| Sports 2000 | 34 | Bristol 450C | Wilson / Mayers |

| Sports 1500 | 37 | Porsche 550 Spyder | Polensky / von Frankenberg |

| Sports 1100 | 49 | Porsche 550 Spyder | Veuillet / Arkus Duntov |

| Sports 750 | 63 | D.B. HBR | Cornet / Mougin |

| Biennial Cup | 37 | Porsche 550 Spyder | Polensky / von Frankenberg |

| Index of Performance | 37 | Porsche 550 Spyder | Polensky / von Frankenberg |

Standings after the race

| Pos | Championship | Points |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | |

18 |

| 2 | |

14 |

| 3 | |

11 |

| 4 | |

8 |

| 5= | |

6 |

| 5= | |

6 |

- Note: Only the top five positions are included in this set of standings.

Championship points were awarded for the first six places in each race in the order of 8-6-4-3-2-1. Manufacturers were only awarded points for their highest finishing car with no points awarded for positions filled by additional cars. Only the best 4 results out of the 6 races could be retained by each manufacturer. Points earned but not counted towards the championship totals are listed within brackets in the above table.

References

- 1 2 http://www.racingsportscars.com/race/Le_Mans-1955-06-12.html

- 1 2 http://wsrp.ic.cz/wsc1955.html

- 1 2 3 John Fitch, “Racing with Mercedes" (Photo Data Research, ISBN 978-0-9705073-6-5, 2005)

- 1 2 3 http://www.sportscardigest.com/1955-24-hours-of-le-mans-race-profile/

- ↑ Frank Foster (5 September 2013). F1: A History of Formula One Racing. BookCaps Study Guides. p. 1968. ISBN 978-1-62107-573-8.

- ↑ Sigur E. Whitaker (23 April 2014). Tony Hulman: The Man Who Saved the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. McFarland. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-7864-7882-8.

- ↑ Gary G. Anderson. Austin-Healey 100, 100-6, 3000 Restoration Guide. MotorBooks International. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-61060-814-5.

- ↑ Spurgeon, Brad (11 June 2015). "On Auto Racing's Deadliest Day". The New York Times Company, Inc. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ↑ http://www.ewilkins.com/wilko/lemans.htm

- ↑ http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00sfptx

- ↑ "Le Mans 1955 - Reel 2 Part 4".

- 1 2 3 4 "Paul Skilleter, Le Mans".

- 1 2 http://www.teamdan.com/archive/wsc/1955/55lemans.html

Further reading

- Quentin Spurring. Le Mans 24 Hours: The Official History of the World’s Greatest Motor Race 1949-59. Haynes Publishing. ISBN 978-1844255375

- Brian Laban. Le Mans 24 Hours: The Complete Story of World’s Most Famous Motor Race. Haynes Publishing. ISBN 978-1852270629

| World Sportscar Championship | ||

|---|---|---|

| Previous race: Mille Miglia |

1955 season | Next race: RAC Tourist Trophy |

External links

- Le Mans 1955 from The Mike Hawthorn Tribute Site – Extensive 1955 Le Mans coverage – reports, analysis, photos/video of race + crash

- Video of accident and aftermath