Amon Carter Museum of American Art

| |

| Established | January 1961[1] |

|---|---|

| Location |

3501 Camp Bowie Boulevard Fort Worth, Texas 76107-2695 (United States) |

| Type | Art[1] |

| Director | Dr. Andrew J. Walker |

| Website | Amon Carter Museum of American Art |

The Amon Carter Museum of American Art (ACMAA) is located in Fort Worth, Texas, in the city's cultural district. The museum's permanent collection features paintings, photography, sculpture, and works on paper by leading artists working in the United States and its North American territories in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The greatest concentration of works falls into the period from the 1820s through the 1940s. Photographs, prints, and other works on paper produced up to the present day are also an area of strength in the museum's holdings.

The collection is particularly focused on portrayals of the Old West by Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell, artworks depicting nineteenth-century exploration and settlement of the North American continent, and masterworks that are emblematic of major turning points in American art history. The "full spectrum" of American photography is documented by 45,000 exhibition-quality prints, dating from the earliest years of the medium to the present.[2] A rotating selection of works from the permanent collection is on view year-round during regular museum hours, and several thousand of these works can be studied online using the Collection tab on the ACMAA's official website. Museum admission for all exhibits, including special exhibits, is free.

The Amon Carter Museum of American Art opened in 1961 as the Amon Carter Museum of Western Art. The museum's original collection of more than 300 works of art by Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell was assembled by Fort Worth newspaper publisher and philanthropist Amon G. Carter, Sr. (1879-1955).[3] Carter spent the last ten years of his life laying the legal, financial, and philosophical groundwork for the museum's creation.[4]

Collection

Western art by Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell

Over 400 works of art by Frederic Remington (1861–1909) and Charles M. Russell (1864–1926) form the ACMAA's core collection of art of the Old West. These holdings include drawings, illustrated letters, prints, oil paintings, sculptures, and watercolors produced by Remington and Russell during their lifetimes. More than sixty of the works by Remington and more than 250 of the works by Russell were purchased by the museum’s namesake, Amon G. Carter, Sr., over a twenty-year span beginning in 1935.[3] Additions to Amon Carter’s original holdings by museum curators have resulted in a collection that contains multiple examples of Remington's and Russell's best work at every stage of their respective careers.[5]

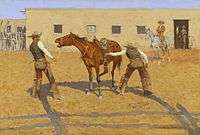

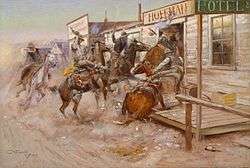

Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell were America's best known and most influential western illustrators. Working from his New York studio except when traveling, Remington produced colorful and masculine images of life in the Old West that shaped public perceptions of the American frontier experience for an eastern audience eager for information.[6] Montana resident Charles Russell, with his cowboy dress, laconic manner, and storytelling prowess, epitomized, in the early twentieth-century, the image of the Cowboy Artist in the eyes of the eastern press.[7]

Though neither artist had lived on the frontier at the height of America’s westward expansion, their drawings, paintings, and sculptures were infused with the action and convincing realism of direct observation. Russell moved to Montana Territory in 1880, nine years before statehood, and had worked as a cowboy for more than a decade before beginning his career as a professional artist.[8] Remington toured Montana in 1881, later owned a sheep ranch in Kansas, and had traversed Arizona Territory in 1886 as an illustrator for Harper's Weekly.[9] These and other experiences enabled both artists to convincingly portray a vast variety of Old West subject matter drawing on real world experiences, historical evidence, and their artistic imaginations.

Noteworthy artworks in the ACMAA collection by Remington and Russell include: 1) Frederic Remington, A Dash for the Timber (1889; see gallery below) -- a work that established Remington as a serious painter when it was exhibited at the National Academy of Design in 1889.[10] 2) Frederic Remington, The Broncho Buster (1895) -- Remington's first attempt to model in bronze and the work that started him on a long secondary career as a sculptor. 3) Frederic Remington, The Fall of the Cowboy (1895) -- an evocation of the fading of the mythic cowboy of legend, anticipating Owen Wister's celebrated novel, The Virginian (1902).[11] 4) Charles M. Russell, Medicine Man (1908) -- a detailed portrait of a Blackfeet shaman, reflecting Russell's empathy with Native American culture.[12] 5) Charles M. Russell, Meat for Wild Men (1924) -- a bronze sculpture that evokes the "grand turmoil" resulting as a band of mounted hunters descends upon a herd of grazing buffalo.[13]

Expeditionary art and depictions of Native American life

The ACMAA houses a wide selection of maps and artworks by European and American documentary artists who, in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, traveled the North American continent in search of new sights and discoveries. Some of these artists worked independently, focusing on subjects or areas of the country of their own choosing. Others served as documentarians on expeditions of continental discovery sent out by the U. S. government or by European sponsors. In these roles, artists were uniquely positioned to record the topography, animal and plant life, and diverse Indian culture of America and its frontiers. Finding and collecting drawings, oil paintings, watercolors, and published lithographs by these European and American documentary artists was one of the museum's earliest goals.[14] Documentary artists represented in the collection include John James Audubon (1785–1851), Karl Bodmer (1809–1893), George Catlin (1796–1872), Charles Deas (1818–1867), Seth Eastman (1808–1875), Edward Everett (1818–1903), Francis Blackwell Mayer (1827–1899), Alfred Jacob Miller (1810–1874), Peter Moran (1841–1914), Thomas Moran (1837–1926), Peter Rindisbacher (1806–1834), John Mix Stanley (1814–1872), William Guy Wall (1792–after 1864), Carl Wimar (1828–1862), and others. See Works on paper (below) for more information on American expeditionary art.

Landscape paintings and coastal scenes

The Hudson River School, one of the critical movements in nineteenth-century American landscape painting, is an important focus of the ACMAA collection. Two major oils by Thomas Cole (1801–1848) and one by Cole’s protégé Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900) anchor the museum’s holdings of signature Hudson River School paintings. The Narrows from Staten Island (1866–68), a panoramic depiction of Staten Island and New York Harbor by Jasper Francis Cropsey (1823–1900), is a notable example of the Hudson River School‘s preoccupation with scenery along the Hudson River Valley and surrounding area (see picture gallery below).

The Pre-Raphaelite movement, a British movement that was briefly influential among some artists of the Hudson River School in the mid-nineteenth century, is exemplified in Woodland Glade (1860) by William Trost Richards (1833–1905) and Hudson River, Above Catskill (1865) by Charles Herbert Moore (1840–1930). The Moore painting depicts an identifiable portion of the Hudson River adjacent to the home of Thomas Cole, making it likely that the painting was intended as a tribute to Cole.

Hudson River School paintings that reflect the influence of Luminism are also found in the ACMAA collection. These include works by Sanford Robinson Gifford (1823–1880), Martin Johnson Heade (1819–1904), John Frederick Kensett (1816–1872), and Fitz Henry Lane (1804–1865). Given its “dark, brooding mystery,” the painting by Heade, Thunder Storm on Narragansett Bay (1868), is considered by many observers to be the artist’s masterpiece.[15]

Other Hudson River School artists represented in the collection by major oil paintings are Robert Seldon Duncanson (1821–1872), David Johnson (1827–1908), and Worthington Whittredge (1820–1910). William Stanley Haseltine (1835–1900) is represented by a preliminary study of rocky coastline along Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island.

The influence of the Hudson River School and Luminism was focused on a western United States location about 1870 when Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902) produced Sunrise, Yosemite Valley. This grandiose example of the artist’s work was completed after Bierstadt’s third trip to the American west.[16] It was added to the ACMAA collection in 1966. Another Hudson River School painter who headed west was Thomas Moran (1837–1926). Moran, famous for his paintings of the Yellowstone region of Wyoming, is represented in the ACMAA collection by his 1874 oil Cliffs of Green River (see picture gallery below).

Figure paintings, portraits, and images of everyday life

Nineteenth-century figure paintings, portraits, and genre pictures (portrayals of everyday life) represent an important chapter in the history of American art development, and several examples of these types of paintings are found in the ACMAA collection. Swimming (1885) by Thomas Eakins (1844–1916) is one of the best-known realist figure paintings in the history of American art.[17] A summation of Eakins’ painting technique and belief system, Swimming was acquired for the ACMAA collection in 1990.[18] Crossing the Pasture (1871–72) by Winslow Homer (acquired 1976) combines the artist’s skills as a figure painter with his gift for storytelling to create a charming image of rural New York life.

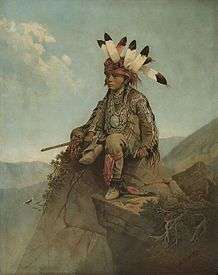

Indian Group (1845) by Charles Deas (1818–1867) explores the physical appearance of Deas' Native American subjects and the perils associated with their nomadic lifestyle (see picture gallery below). The Potter (1889) by George de Forest Brush (1855–1941) is another example in the ACMAA collection of an artist's exacting and nuanced method of depicting an indigenous American sitter. Attention Company! (1878) by William M. Harnett (1848–1892) is the only known figural composition by this American master of trompe-l'œil (“fool the eye”) painting.[19]

A major historical genre painting by William T. Ranney (1813–1857) is in the ACMAA collection. Ranney’s Marion Crossing the Pedee (1850) exhibits the artist’s great skill as a figure painter and use of that skill to entertain and educate his nineteenth-century audience. Notable genre paintings by Conrad Wise Chapman (1842–1910), Francis William Edmonds (1806–1863), Thomas Hovenden (1840–1895), and Eastman Johnson (1824–1906) are also housed in the ACMAA collection.

Portraitist John Singer Sargent (1856–1925) is represented in the museum’s collection by formal portraits of two American subjects, Alice Vanderbilt Shepard (1888), and Edwin Booth (1890; see picture gallery below).

Still life paintings and sculpture

%2C_Wrapped_Oranges%2C_1889._Oil_on_canvas._Amon_Carter_Museum_of_American_Art.jpg)

Trompe-l'œil (“fool the eye”) paintings and classic still-life paintings make up a prominent component of the ACMAA collection. Ease (1887) by William M. Harnett (1848–1892) is a large and eloquent example of the trompe-l'œil genre and one that amply demonstrates the allure of Harnett’s trompe-l'œil illusions for his nineteenth-century patrons.[20] John Frederick Peto (1854–1907), a William Harnett contemporary who worked in relative obscurity, is represented in the collection by two highly accomplished trompe-l'œil compositions, Lamps of Other Days (1888) and A Closet Door (1904-06). Other trompe-l'œil paintings in the ACMAA collection were created by De Scott Evans (1847–1898) and John Haberle (1853–1933).

America’s first recognized still-life painter, Raphaelle Peale (1774–1825), is represented in the ACMAA collection by an 1813 composition Peaches and Grapes in a Chinese Export Basket. Other classic American still lifes featuring fruit or flowers include Wrapped Oranges (1889) by William J. McCloskey (1859–1941) and Abundance (after 1848) by Severin Roesen (1815–after 1872).

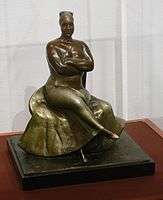

The ACMAA sculpture collection provides historical context for the museum’s deep holdings of bronze sculpture by Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell, as well as acknowledging the importance of sculpture in the wider history of American art. As such, the collection contains works created by leading individuals in both the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The Choosing of the Arrow (1849) by Henry Kirke Brown (1814–1886) is one of the earliest bronzes cast in America. Slightly later bronze sculptures, The Indian Hunter (1857-59) and The Freedman (1863), both by John Quincy Adams Ward (1830–1910), are also in the collection. Bust of a Greek Slave (after 1846) by Hiram Powers (1805–1873) is an example of an American neoclassical work carved in marble.

Two American sculptors who enjoyed great success during their lifetimes, Frederick MacMonnies (1863–1937) and Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848–1907), are represented in the ACMAA collection by cast bronze works created in the late nineteenth century. Alexander Phimister Proctor (1860–1950) and Anna Hyatt Huntington (1876–1973) are represented by bronzes created in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries respectively. A bronze sculpture by Solon Borglum (1868–1922), who, like Remington and Russell, specialized in depictions of Old West subjects, and a two-piece bronze by Paul Manship (1885–1966), Indian Hunter and Pronghorn Antelope (1914), are in the collection as well.

The experimentation of early twentieth-century artists with nature-based abstraction and direct carving techniques from natural materials is seen in works by John Flannagan (1895–1942), Robert Laurent (1890–1970), and Elie Nadelman (1882–1946). Signature works by Alexander Calder (1898–1976) and Louise Nevelson (1899–1988) are among the mid-twentieth century sculptural pieces in the collection. Nevelson’s Lunar Landscape is a large, painted-wood construction that dates to 1959-60 (see picture gallery below).

American Impressionist paintings and 20th-century modernist works

The horizons of American art in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century expanded rapidly, fueled by major artistic advances in Europe. Before 1920, French Impressionism was one of the most important influences at work in cutting-edge American art circles. With a growing awareness of Impressionism as a valid approach to depicting nature, many prominent artists in the eastern United States adopted its tenets, leading to a recognized school of American Impressionism. The ACMAA collection contains several examples of American Impressionism by some of the genre’s most accomplished painters.

Idle Hours (about 1894) by William Merritt Chase (1849–1916) anchors the ACMAA holdings of American Impressionist paintings. Chase’s student and protégé Julian Onderdonk (1882–1922) is represented by a Texas scene, A Cloudy Day, Bluebonnets near San Antonio, Texas (1918). Flags on the Waldorf (1916) is a signature New York work by Childe Hassam (1859–1935). Other well-known American Impressionist painters who have pieces in the collection are Mary Cassatt (1844–1926), Willard Metcalf (1858–1925), and Dennis Miller Bunker (1861–1890; see picture gallery below).

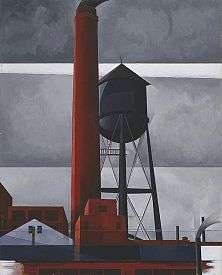

New York photographer Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) befriended and championed several of the most visionary modern painters to emerge in early twentieth-century America. Five modern artists who were closely identified with Stieglitz’s circle are represented in the ACMAA collection. They are Charles Demuth (1883–1935), Arthur G. Dove (1880–1946), Marsden Hartley (1877–1943), John Marin (1870–1953), and Georgia O'Keeffe (1887–1986). The collection houses early works by Demuth, Dove, Hartley, and O’Keeffe, produced between 1908 and 1918, and a focused group of later paintings by Dove, Hartley, Marin, and O’Keeffe that capture their response to the light and color of the New Mexican landscape near Taos. Charles Demuth’s Chimney and Water Tower (1931), painted in the artist’s hometown of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, depicts a local linoleum factory as a grid of austere, monumental forms and passages of steel gray, blue, and deep red.[21] Chimney and Water Tower entered the ACMAA collection in 1995.

Several important paintings by American modernist Stuart Davis (1892–1964) are housed in the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, including an early self-portrait painted in 1912 and a work from his Egg Beater series, Egg Beater No. 2 (1928). American modernists represented in the AMCAA collection also include Josef Albers (1888–1976), Will Barnet (1911-2012), Oscar Bluemner (1867–1938), Morton Schamberg (1881–1918), Ben Shahn (1898–1969), Charles Sheeler (1883–1965), Joseph Stella (1877–1946), and others (see picture gallery below).

Photography

The Amon Carter Museum of American Art is one of the country’s major repositories for historical and fine art photographs.[22] The ACMAA has over 350,000 photographic works in its collection, including 45,000 exhibition-quality prints. These holdings span the complete history of photographic processes used in America from daguerreotypes to digital. Photography’s central role in documenting American culture and history, and the medium’s evolution as a significant and influential art form in the twentieth-century to the present, are the themes around which the ACMAA photography collection is organized.

The personal archives of photographers Carlotta Corpron (1901–1988), Nell Dorr (1893–1988), Laura Gilpin (1891–1979), Eliot Porter (1901–1990), Erwin E. Smith (1886–1947), and Karl Struss (1886–1981) are prominent collection resources.[2] Finding aids and guides for these and other monographic collections are available online under the Collections/Photographs/Learn More tabs on the ACMAA website.

The ACMAA photography collection contains early images of Americans at war, anchored by 55 Mexican-American War (1847-1848) daguerreotypes. The collection houses a copy of Alexander Gardner’s two-volume work, Gardner's Photographic Sketch Book of the Civil War and a copy of Photographic Views of Sherman’s Campaign (1865) by George Barnard. A group of more than 1,400 nineteenth and early twentieth-century portraits of Native Americans that originated with the Bureau of American Ethnology is another of the collection’s highlights, along with a complete set of Edward Curtis's The North American Indian.

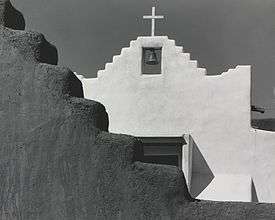

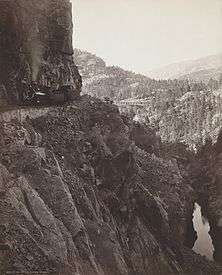

The ACMAA’s collection of nineteenth-century landscape photographs includes images by John K. Hillers (1843–1925), William Henry Jackson (1843–1942), Timothy H. O'Sullivan (1840–1882), Andrew J. Russell (1830–1902), and Carleton E. Watkins (1829–1916). Twentieth-century master images by Ansel Adams (1902–1984) are complimented by later twentieth-century landscapes from the studios of William Clift (b. 1944), Frank Gohlke (b. 1942), and Mark Klett (b. 1952).

Fine art photographs by Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) are the collection’s most significant works from the turn-of-the-twentieth-century Photo-Secession movement, a crusade which Stieglitz led. The work of the Photo-Secessionists and other leading photographers of the period is also documented in complete runs of Camera Notes (published 1897-1903), Camera Work (published 1903-1917), and 291 (published 1915-1916).

Substantive holdings of twentieth-century documentary photographs include works by Berenice Abbott (1898–1991); prints produced over twenty-five years in connection with Dorothea Lange’s The American Country Woman photographic essay; Texas images from the Standard Oil of New Jersey Collection; and project photographs from the 1986 statewide survey Contemporary Texas: A Photographic Portrait. Additionally, twentieth-century documentary photographs by Russell Lee (1903–1986), Arthur Rothstein (1915–1985), Marion Post Wolcott (1910–1990), and many others are housed in the museum’s collection.

Other substantive groups of twentieth-century photographs in the ACMAA collection are organized around the careers of Robert Adams (b. 1937), Barbara Crane (b. 1928), Frank Gohlke (b. 1942), Robert Glenn Ketchum (b. 1947), Clara Sipprell (1885–1975), Brett Weston (1911–1993), and Edward Weston (1886–1958).

The ACMAA owns a complete set of prints from Richard Avedon’s In the American West series, a project commissioned by the ACMAA in 1979. In recent years the museum has largely focused on acquiring and displaying photographs by contemporary artists including Dawoud Bey (b. 1953), Sharon Core (b. 1965), Katy Grannan (b. 1969), Todd Hido (b. 1968), Alex Prager (b. 1979), Mark Ruwedel (b. 1954), and Larry Sultan (1946–2009).

Works on paper

Much of America’s aesthetic, economic, and social history is found in works on paper, a category that includes drawings, prints, and watercolors.[23] The ACMAA began to actively collect works on paper in 1967.[24] The collection today numbers several thousand items by noted artists of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to the present.[25] Drawings and paintings range from preliminary studies to fully realized compositions. Most nineteenth-century prints originated as reproductions intended for dissemination to the public and depict subjects relevant to the American experience. Twentieth-century and later prints are fine art prints made by a variety of processes as a means of artistic self-expression.

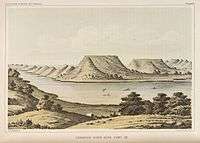

Prints that stem from early western surveys conducted by the United States War Department and the United States Department of the Interior are important components of the works on paper collection. These prints were typically based on field sketches by artists who accompanied the expeditions. They provide unique views of the western landscape, Indian life, natural history, ancient Spanish culture, and life in nineteenth-century American frontier communities. The Frémont Expeditions (1842-44), Emory Expedition (1846-47), Abert Expedition (1846-47), and Simpson Expedition (1849) are among the sources of western survey prints collected by the ACMAA.

The ACMAA’s nineteenth-century print collection also includes a copy of the landmark Hudson River Portfolio (1821-25) based on the work of painter William Guy Wall (1792–after 1864) and engraver John Hill (1770–1850); original copper plate etchings of Native Americans as depicted in field studies by Karl Bodmer (1809–1893); a complete set of planographic prints from George Catlin’s North American Indian Portfolio (1844); and ornithological prints from John James Audubon’s landmark book The Birds of America (published 1827-38).

Examples of work in the collection by other noted expeditionary artists include rare nineteenth-century field studies by Edward Everett (1818–1903), Richard H. Kern (1821–1853), John H. B. Latrobe (1803–1891), Alfred Jacob Miller (1810–1874), and Peter Rindisbacher (1806–1834); nineteenth-century views of the American West by John Mix Stanley (1814–1872) and Henry Warre (1819–1898); and early views of San Francisco by Thomas A. Ayres (1816–1858). See Expeditionary art and depictions of Native American life (above) for more information on American expeditionary art and artists.

Preeminent American artists of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries like Winslow Homer (1836–1910), George Inness (1825–1894), John La Farge (1835–1910), and famed expatriates John Singer Sargent (1856–1925) and James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903) are each represented by high-quality drawings and/or paintings in the ACMAA works on paper collection.[24]

Other artists in the works on paper collection who are associated with major movements in American art include American Pre-Raphaelites Fidelia Bridges (1834–1923), Henry Farrer (1844–1903), John Henry Hill (1839–1922), Henry Roderick Newman (1843–1917), and William Trost Richards (1833–1905); Ashcan School illustrator John Sloan (1871–1951); and leading twentieth-century modernists Charles Demuth (1883–1935), Arthur Dove (1880–1946), John Marin (1870–1953), Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986), Morton Livingston Schamberg (1881–1918), and Abraham Walkowitz (1878–1965).[26]

A master set of over 200 lithographs by American realist painter George Wesley Bellows (1882–1925) is one of the highlights of the ACMAA’s works on paper collection. Leading American printmakers Martin Lewis (1881–1962), Louis Lozowick (1892-1973), and Reginald Marsh (1898-1954) are each represented by multiple examples of their graphic work. Also housed in the collection are early works by Edward Hopper (1882–1967) and a complete set of prints by modernist Stuart Davis (1892–1964). An early watercolor by Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000), acquired in 1987, marks the ascension of this important artist’s career.

The ACMAA collection houses almost 2,500 fine art lithographs made at the Tamarind Lithography Workshop in Los Angeles, California between 1960 and 1978. The museum also houses an important collection of drawings, watercolors, and prints by early Texas artist Bror Utter (1913–1993), including Utter’s 1957-58 studies of vanishing Fort Worth architecture. Most recently, the ACMAA added two important series of lithographs to these holdings, one by Glenn Ligon (b. 1960) and another by Sedrick Huckaby (b. 1975).

Library and archives

|

Amon Carter Museum of American Art Library Reading Room |

The ACMAA library is a 150,000 item art reference library available for use by museum curators, researchers, and interested members of the public. The library provides access to a 50,000 book collection, augmented by related collections of microform, periodicals and journals, auction catalogs, and ephemera.[27] The library’s holdings are non-circulating and organized around the study of American art, photography, and culture from Colonial times to the present, with an emphasis on materials that enhance understanding of objects in the museum’s permanent art collection and the milieu in which these objects were created.

The ACMAA library’s microform holdings include 14,000 microfilm reels of nineteenth-century newspapers, periodicals, books, and other primary material. These holdings also include more than 50,000 microfiches of auction and exhibition catalogues, ephemera, and other material. Specific microform sets include the Knoedler Library on Microfiche (art auction and exhibition catalogs), New York Public Library Artists File, New York Public Library Print File, and America, 1935-1946 (photographs from the Farm Security Administration and the Office of War Information in the Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress).[27] The Amon Carter Museum of American Art is the mid-country research affiliate of the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.[27] In this role, the ACMAA library offers access to 7,500 microfilm reels of unrestricted material from the Archives of American Art representing about fifteen-million primary, unpublished documents related to American artists, galleries, and collectors.[28]

The library’s Vertical File/Ephemera collection contains a wide variety of loose material and small publications on artists, museums, commercial galleries, and other art organizations. Included in this collection are biographical files, arranged by name, with coverage of about 9,000 artists, photographers, and collectors.[27] These biographical files offer researchers a wealth of newspaper clippings, small exhibition catalogs, resumes, journal and periodical articles, reproductions, event invitations and announcements, portfolios, bibliographies, and similar material from which to draw.

The ACMAA library houses a number of rare illustrated books. These titles are useful for their textual information and valuable as works of art for their original prints. Among the illustrated books in the library collection are American Ornithology, or, the Natural History of the Birds of the United States (Philadelphia: Bradford and Inskeep, 1809-14), the first bird book published in the United States and the first outstanding American color plate book; and The Aboriginal Port-folio (Philadelphia: J.O. Lewis, 1835-36), the first color plate book published on the North American Indian. Other illustrated books owned by the library are highlighted under the Collection tab on the ACMAA website, and many of the illustrations within these books are digitized and searchable.[29]

The museum archives contain private papers and records originating from individuals, usually artists or photographers, that are often integrally connected to the museum's art collection. Among these records are the personal archives of photographers Laura Gilpin (1891–1979), Eliot Porter (1901–1990), and Karl Struss (1886–1981).[30] The archives also house the business records of the Roman Bronze Works (est. 1897-closed 1988) of Queens, New York, long one of America’s premier art bronze foundries, and a range of documents related to the ACMAA's institutional history.

In 1996, the ACMAA library partnered with the libraries of the Kimbell Art Museum and the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth to create the Cultural District Library Consortium (CDLC). The purpose of the consortium was to explore new ways of sharing the resources of the three Fort Worth institutions via online public access. In 1998, with technical assistance from the library at Texas Christian University, the three museums launched an online CDLC catalog that allows website visitors access to the combined collections of all three art museum libraries.[31] Today, the CDLC catalog also gives access to the libraries of the National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame, and the Botanical Research Institute of Texas (BRIT). To search the ACMAA library holdings, click Search the ACMAA Library Catalog in the External links section (below).

Professional assistance and access to items in the Amon Carter Museum of American Art library is provided in the library reading room during the stated hours of operation. More information is available under the Library tab on the ACMAA website.

History

An admission-free museum of western art was conceived by Amon G. Carter, Sr. (1879–1955), publisher of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, a large-circulation, daily newspaper in Fort Worth, Texas. Carter and his wife, Nenetta Burton Carter, took a key step toward the museum’s creation in 1945 when the Amon G. Carter Foundation, a Texas non-profit foundation, was formed, and the Carters transferred much of their wealth into it for the purpose of providing seed money to support an array of civic causes.[32] At the time the foundation was incorporated, Amon Carter had been actively collecting art by Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell for a decade.[33]

On October 3, 1950, Carter informed the City of Fort Worth of his intention to “erect and equip” a museum and present it to the city.[34] In 1951, the Amon G. Carter Foundation purchased a portion of the museum’s future site to protect the land from commercial encroachment.[35] Following Amon Carter’s death in June 1955, his last will and testament empowered the foundation to provide for a museum to house his art collection and "be operated as a nonprofit artistic enterprise for the benefit of the public and to aid in the promotion of the cultural spirit in the city of Fort Worth and vicinity, to stimulate the artistic imagination among young people residing there.”[36]

A chance meeting between Amon Carter’s daughter and New Yorker Philip C. Johnson (1906-2005) at a Houston dinner party led to the commissioning of Johnson as the future museum’s lead architect.[37] Ruth Carter Stevenson (who was Ruth Carter Johnson at the time and no relation to the architect) had assumed the role of project manager for the new museum and was in a position to offer Philip Johnson the job.[38] In February 1959, the City of Fort Worth and the Amon G. Carter Foundation entered into a contract for the creation of a museum of western art, with the city providing the remainder of the land needed to build the museum.[39] Construction began in 1960, and the Amon Carter Museum of Western Art opened to the public on January 21, 1961 (see building history below).

Raymond T. Entenmann, director of the Fort Worth Art Center, served as the Amon Carter’s acting administrator during the museum’s early months.[40] Mitchell A. Wilder (1913-1979), a seasoned museum director working in Los Angeles, arrived in August 1961 to begin work as the museum’s director.[41]

The museum’s articles of incorporation and bylaws were adopted in the fall of 1961, and a Board of Trustees was appointed.[42] In their early discussions, Wilder and the board decided that the museum’s programs and permanent collection should reflect many aspects of American culture, both historic and contemporary.[42] This decision paved the way for an expansion of the permanent collection that first focused on acquiring American art from the nineteenth-century and, later, the twentieth. Under Wilder’s guidance, the museum collected heavily in the areas of nineteenth-century American art and photography. Wilder also established an academic publishing presence and built a record of organizing groundbreaking exhibitions. The museum published Paper Talk: The Illustrated Letters of Charles M. Russell in 1962, the first of many books on the art of the American West to originate from the Amon Carter.[43] In 1966, Wilder reintroduced the paintings of Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986) to the nation by organizing a ninety-five piece retrospective of her work.[44]

The following year, 1967, American Art–20th Century: Image to Abstraction brought more than one hundred paintings by America’s leading early modernists to Fort Worth from New York. Blips and Ifs (1963–64), the final painting by Stuart Davis (1892–1964), was acquired for the museum from this exhibition, signaling a fundamental redefinition of the museum’s collecting scope.[45] Mitchell Wilder’s embrace of the museum’s collecting mandate led to two building expansions during his tenure, including a major addition in 1977 that doubled the size of the museum (see building history below).

Mitchell Wilder died in 1979 after a brief illness. Four other directors have headed the museum in the years since. They are Jan Keene Muhlert (1980–95), Dr. Rick Stewart (1995–2005), Dr. Ron Tyler (2006–11), and Dr. Andrew J. Walker (2011–present). Each worked closely with Amon Carter’s daughter, Ruth Carter Stevenson (1923–2013), in determining the museum’s course. Stevenson had spent the final years of her father's life in conversation with him about his concepts for a museum and the role it should play in Fort Worth civic life.[38] It was this familiarity with his vision, and her extraordinarily high standards, that would bring Stevenson into a leading role in the museum’s development.

Jan Keene Muhlert oversaw an aggressive acquisitions program that brought works by William Merritt Chase (1849–1916), Thomas Cole (1801–1848), Arthur Dove (1880–1946), Childe Hassam (1859–1935), and David Johnson (1827–1908) into the collection, crowned by the acquisition in 1990 of Swimming by Thomas Eakins (1844–1916).[46] The purchase of the Eakins masterpiece required a capital campaign to raise ten million dollars and drew on every resource available to Muhlert. Dr. Rick Stewart, Muhlert’s successor, is a nationally recognized scholar on the work of Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell. During his tenure as director, Dr. Stewart added major works to the museum’s collection by Stuart Davis (1892–1964), Marsden Hartley (1877–1943), and John Singer Sargent (1856–1925). Stewart oversaw the challenging, two-year closure during which two previous expansions and the museum’s physical plant were demolished. In their place a much larger facility was erected, culminating in a grand reopening in 2001.[47] When Dr. Stewart stepped down as director, he was named the museum’s senior curator of western painting and sculpture.

Dr. Ron Tyler returned to the Amon Carter in 2006 as director. (Dr. Tyler began his museum career at the museum from 1969 to 1986.) During his tenure as director, the museum presented major exhibitions of the work of Alfred Jacob Miller (1810–1874) and William Ranney (1813–1857), and an important exhibition of African-American art from the private collection of Harmon and Harriet Kelley. Paintings by George de Forest Brush (1855–1941) and Charles Sheeler (1883–1965), as well as a complete, 20-volume set of Edward Sheriff Curtis’ The North American Indian (1907–1930), were added to the museum’s permanent collection during Dr. Tyler’s administration.[48] Dr. Andrew J. Walker has led the Amon Carter since 2011. Under Dr. Walker's leadership, the ACMAA has hosted major exhibitions of work by George Caleb Bingham (1811–1879), Will Barnet (1911–2012), and the circle of New York modernists led by artist John Graham (1886–1961). He has overseen additions to the permanent collection of works by Robert Seldon Duncanson (1821–1872), Raphaelle Peale (in memory of Ruth Carter Stevenson), and John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), and he initiated major upgrades to the museum’s digital presence, including the Connecting to Exhibitions digitization project, a two-year initiative that will allow online access to many of the museum’s previous art exhibitions.[49]

In 1977, on the occasion of the opening of Philip Johnson-designed expansion, the Amon Carter Museum of Western Art became the Amon Carter Museum. In 2011, on the occasion of the museum’s 50th anniversary, the museum was renamed the Amon Carter Museum of American Art.

Building

Architect Philip C. Johnson (1906–2005) maintained a forty-year association with the Amon Carter Museum of American Art as the designer of the institution’s original building and two major expansions. The Amon G. Carter Foundation first commissioned Johnson in 1958 to devise a museum building that would showcase a core collection of western art and also serve as a memorial to the museum’s founder.[50] At the time Johnson won this commission he was also overseeing construction of the new Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute Museum of Art in Utica, New York.[51] Johnson found the Carter museum project particularly inspiring because of the spectacular view from the proposed museum’s building site on a gently sloping hillside overlooking downtown Fort Worth.[52] Amon G. Carter, Sr. had personally chosen the site in 1951.[35] Johnson placed the museum building as far up the hillside as possible in order to maximize this panoramic view to the east.[53]

Johnson designed a two-story portico with five arches that faced east toward the city’s skyline. The arches and their tapered support columns were clad in creamy Texas shellstone. The remaining three sides of the 20,000-square-foot building were also covered with shellstone cladding. Sheltered by the arched portico, the museum's front wall consisted of a two-story curtain of glass windows with bronze mullions.[35] The main entrance lead directly into a two-story hall adorned with the same type of shellstone used on the exterior, teak wall coverings, and a floor of pink and gray granite. Beyond the main hall were five small galleries of equal size for the display of art. On the mezzanine level were five similar galleries, each with a balcony that overlooked the main hall. These mezzanine galleries served as library and office spaces.[35] To take advantage of the expanse between the two-story portico and the site’s eastern boundary, Johnson designed a series of broad steps and terraces extending away from the building, with an expansive sunken, grassy plaza as the centerpiece, pointing toward the city’s center.[36]

The museum and grounds opened to the public on January 21, 1961, as the Amon Carter Museum of Western Art. Reaction by critics to Philip Johnson's design was generally favorable. In a March 1961 article, "Portico on a Plaza," the Architectural Forum called it "an exceedingly handsome building -- beautifully situated and beautifully illuminated."[54] Russell Lynes, writing in the May 1961 Harper's, summed up his reaction by calling it "Mr. Johnson's jewel box." [55]

Although the museum was conceived as a small memorial institution, it almost immediately became a collecting museum, and the space afforded by the existing facility quickly became inadequate.[56] In 1964, three years after the museum first opened, a 14,250-square-foot addition was completed on the west side of the original building to provide room for offices, a bookstore, a research library, and an art-storage vault.[35] Joseph R. Pelich (1894-1968) of Fort Worth, an associate architect of the original building, carried out the work after Philip Johnson expressed little interest in taking on the project.[57]

The museum opened a second major addition, this one designed by Philip Johnson and his partner, John Burgee, in 1977. The 1977 addition, which left the 1961 building and 1964 addition intact, expanded the museum's area by 36,600 square feet, more than doubling its original size.[35] The expansion, which included a three-story section, enclosed the triangular space at the far western end of the building site, thus bringing the physical plant to its western-most limit.[57] Johnson’s 1977 addition created an administrative wing, a 105-seat auditorium, a two-story storage vault, a spacious library, and two interior grassed courts that insulated occupants of the library and administrative offices from heavy traffic passing nearby.

On November 17, 1998, museum trustees announced plans to expand the museum yet again. Museum personnel had been in discussion with Philip Johnson for some time regarding the need to alter Johnson’s 1977 addition.[56] Johnson’s solution was to demolish both the 1964 and 1977 additions and create a new, much larger structure behind the 1961 building. Philip Johnson spearheaded the new design in collaboration with his partner Alan Ritchie. It would be one of the last projects on which Johnson worked.[56] In August 1999 the museum was closed to the public for an extended period while the 1961 building was refurbished, the 1964 and 1977 additions were removed, and the new addition constructed.

The current museum building reopened to the public on October 21, 2001. The 2001 expansion, which increased the museum’s available space by 50,000 square feet, rests on the same footprint as the earlier additions.[56] It is clad in dark Arabian granite so as to recede visually from the light-colored shellstone of the 1961 building.[56] The expansion’s most arresting feature is a centrally located atrium, rising fifty-five feet above the floor and topped by a curved roof with side windows, referred to as the Lantern.[56] The atrium’s interior walls are clad in the signature shellstone. A double stairway gives access from the atrium to a complex of second-floor galleries where selections from the museum’s permanent collection, along with special exhibitions, are on display.[56] In this new alignment, most of the galleries in the 1961 building, including the mezzanine area where the library and offices were once located, are used for rotating exhibitions of paintings and sculpture by Remington and Russell from Amon G. Carter’s original collection.

Other notable features of Philip Johnson’s 2001 expansion include a 160-seat auditorium, complete with advanced distance-learning technology; climate-controlled vaults for both cool and cold photography storage; dedicated laboratory space for the conservation of photographs and works on paper; a state-of-the-art research library and archives storage facility; and a greatly expanded museum bookstore.[58]

More American art from the collection

-

Plate 10 from The art of colouring and painting landscapes in water colours, Baltimore: Fielding Lucas, 1815

-

Charles Deas (1818–1867), Indian Group, 1845

-

Albert Sands Southworth (1811–1894) and Josiah Hawes (1818–1901), [Two women posed with a chair], ca. 1850

-

William Sharp (1803–1875), Victoria Regia - Intermediate Stages of Bloom, 1854

-

Heinrich Möllhausen (1825–1905), Canadian River Near Camp 38, 1855

-

David Johnson (1827–1908), Eagle Cliff, Franconia Notch, New Hampshire, 1864

-

Martin Johnson Heade (1818–1904), Marshfield Meadows, Massachusetts, 1866–76

-

Jasper Francis Cropsey (1823–1900), The Narrows from Staten Island, 1868

-

Robert Seldon Duncanson (1821–1872), The Caves, 1869

-

George Caleb Bingham (1811–1879), View of Pike's Peak, 1872

-

Thomas Moran (1837–1926), Cliffs of Green River, 1874

-

Mary Cassatt (1844–1926), Woman Standing, Holding a Fan, 1878–79

-

Thomas Eakins (1844–1916), Swimming, 1885

-

Dennis Miller Bunker (1861–1890), In the Greenhouse, 1888

-

John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), Alice Vanderbilt Shepard, 1888

-

John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), Edwin Booth, 1890

-

Frederic Remington (1861–1909), A Dash for the Timber, 1889

-

Frederic Remington (1861–1909), His First Lesson, 1903

-

Charles M. Russell (1864–1926), In Without Knocking, 1909

-

Erwin E. Smith (1886–1947), A wrangler keeping an eye on the remuda grazing below in an arroyo, 1910

-

Morton Livingston Schamberg (1881–1918), Figure, 1913

-

Gaston Lachaise (1882–1935), Woman Seated, modeled 1918, cast 1925

-

Charles Sheeler (1883–1965), Conversation - Sky and Earth, 1940

-

Louise Nevelson (1899–1988), Lunar Landscape, 1959–60

See also

References

- 1 2 Amon Carter Museum: About, ARTINFO, 2008, retrieved 2008-07-28

- 1 2 Roark, Carol; et al. (1993). Catalogue of the Amon Carter Museum Photography Collection. Fort Worth, Texas: Amon Carter Museum. pp. Introduction xi. ISBN 0-88360-063-3.

- 1 2 Stewart, Rick (2001). The Grand Frontier: Remington and Russell in the Amon Carter Museum. Fort Worth: Amon Carter Museum. p. 3. ISBN 0-88360-095-1.

- ↑ Junker, Patricia; et al. (2001). An American Collection: Works from the Amon Carter Museum. New York: Hudson Hills Press in association with the Amon Carter Museum. pp. 12–14. ISBN 1-55595-198-8.

- ↑ Shaw, Punch (14 October 2001). "Wonders of the Western World: The Masterworks of Remington and Russell will now be more visible than ever". archive. Fort Worth Star-Telegram. pp. 3D. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- ↑ Dippie, Brian (1982). Remington and Russell: The Sid Richardson Collection. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press Austin. p. 9. ISBN 0-292-77027-8.

- ↑ Dippie, Brian (1982). Remington and Russell: The Sid Richardson Collection. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press Austin. p. 12. ISBN 0-292-77027-8.

- ↑ Dippie, Brian (1982). Remington and Russell: The Sid Richardson Collection. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press Austin. p. 11. ISBN 0-292-77027-8.

- ↑ Dippie, Brian (1982). Remington and Russell:The Sid Richardson Collection. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press Austin. pp. 8–9. ISBN 0-292-77027-8.

- ↑ Stewart, Rick (2005). The Grand Frontier. Fort Worth: Amon Carter Museum. pp. 8–9. ISBN 0-88360-098-6.

- ↑ Stewart, Rick (2005). The Grand Frontier. Fort Worth: Amon Carter Museum. p. 19. ISBN 0-88360-098-6.

- ↑ Stewart, Rick (2005). The Grand Frontier. Fort Worth: Amon Carter Museum. p. 42. ISBN 0-88360-098-6.

- ↑ Stewart, Rick (1994). "Charles M. Russell:Sculptor". Fort Worth: Amon Carter Museum. pp. 286–290.

- ↑ Ayres, Linda; et al. (1986). American Paintings: Selections from the Amon Carter Museum. Birmingham, AL: Oxmoor House. pp. vii–x. ISBN 0-8487-0694-3.

- ↑ Ayres, Linda; et al. (1986). American Paintings: Selections from the Amon Carter Museum. Birmingham, AL: Oxmoor House. p. 10. ISBN 0-8487-0694-3.

- ↑ Ayres, Linda; et al. (1986). American Paintings: Selections from the Amon Carter Museum. Birmingham, AL: Oxmoor House. p. 20. ISBN 0-8487-0694-3.

- ↑ Bolger, Doreen, ed. (1996). Thomas Eakins and the Swimming Picture. Fort Worth: Amon Carter Museum. pp. Introduction vii. ISBN 0-88360-085-4.

- ↑ Junker, Patricia; et al. (2001). An American Collection: Works from the Amon Carter Museum. New York: Hudson Hills Press in association with the Amon Carter Museum. pp. 112–113. ISBN 1-55595-198-8.

- ↑ Junker, Patricia; et al. (2001). An American Collection: Works from the Amon Carter Museum. New York: Hudson Hills Press in association with the Amon Carter Museum. pp. 96–97. ISBN 1-55595-198-8.

- ↑ Junker, Patricia; et al. (2001). An American Collection: Works from the Amon Carter Museum. New York: Hudson Hills Press in association with the Amon Carter Museum. pp. 116–117. ISBN 1-55595-198-8.

- ↑ Junker, Patricia; et al. (2001). An American Collection: Works from the Amon Carter Museum. New York: Hudson Hills Press in association with the Amon Carter Museum. p. 220. ISBN 1-55595-198-8.

- ↑ Junker, Patricia; et al. (2001). An American Collection: Works from the Amon Carter Museum. New York: Hudson Hills Press in Association with the Amon Carter Museum. p. 15. ISBN 1-55595-198-8.

- ↑ Myers, Jane (2011). The Allure of Paper: Watercolors and Drawings from the Amon Carter Museum of American Art. Fort Worth: Amon Carter Museum of American Art. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-4507-6353-0.

- 1 2 Myers, Jane (2011). The Allure of Paper: Watercolors and Drawings from the Amon Carter Museum of American Art. Fort Worth: Amon Carter Museum of American Art. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-4507-6353-0.

- ↑ "Works on Paper Amon Carter Museum". Amon Carter Museum of American Art. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- ↑ Myers, Jane (2011). The Allure of Paper: Watercolors and Drawings from the Amon Carter Museum of American Art. Fort Worth: Amon Carter Museum of American Art. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-4507-6353-0.

- 1 2 3 4 "Library Collections". Amon Carter Museum of American Art. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- ↑ "Archives of American Art". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- ↑ "ACMAA Illustrated Books". Amon Carter Museum of American Art. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- ↑ "Museum Archives". Amon Carter Museum of American Art. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- ↑ "CDLC Basic Search". Texas Christian University library. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- ↑ "Amon G Carter Foundation". Amon G Carter Foundation. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ↑ Junker, Patricia; et al. (2001). An American Collection: Works from the Amon Carter Museum. New York: Hudson Hills Press in association with the Amon Carter Museum. p. 11. ISBN 1-55595-198-8.

- ↑ Junker, Patricia; et al. (2001). An American Collection: Works from the Amon Carter Museum. New York: Hudson Hills Press in association with the Amon Carter Museum. p. 13. ISBN 1-55595-198-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Martin, Carter (1996). 150 Years of American Art: Amon Carter Museum Collection. Fort Worth: Amon Carter Museum. p. 5. ISBN 0-88360-087-0.

- 1 2 Junker, Patricia; et al. (2001). An American Collection: Works from the Amon Carter Museum. New York: Hudson Hill Press in association with the Amon Carter Museum. p. 14. ISBN 1-55595-198-8.

- ↑ Wright, George (1997). Monument for a City: Philip Johnson's Design for the Amon Carter Museum. Amon Carter Museum. p. 25. ISBN 0-88360-088-9.

- 1 2 Martin, Carter (1996). 150 Years of American Art: Amon Carter Museum Collection. Fort Worth: Amon Carter Museum. p. 3. ISBN 0-88360-087-0.

- ↑ "City Council Approves Art Museum Contract". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. 28 February 1959. pp. 1 and 6. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ↑ "Museum Dedicated, Will Open Tuesday". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. 23 January 1961. p. 1. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ↑ "Two Leaders Join Art Community". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. 6 August 1961. pp. Section 3 pp. 14. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- 1 2 Ayres, Linda; et al. (1986). American Paintings: Selections from the Amon Carter Museum. Birmingham, Alabama: Oxmoor House. pp. Intro. vii. ISBN 0-8487-0694-3.

- ↑ "Amon Carter Museum of American Art: Institutional Timeline" (PDF). Amon Carter Museum of American Art. p. 3. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ↑ "Amon Carter Museum of American Art: Institutional Timeline" (PDF). Amon Carter Museum of American Art. p. 4. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ↑ "Amon Carter Museum of American Art: Institutional Timeline" (PDF). Amon Carter Museum of American Art. p. 5. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ↑ "Amon Carter Museum of American Art: Institutional Timeline" (PDF). Amon Carter Museum of American Art. pp. 9 –12. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ↑ "Amon Carter Museum of American Art: Institutional Timeline" (PDF). Amon Carter Museum of American Art. pp. 13 –15. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ↑ "Welcome to the Amon Carter Press Room". Amon Carter Museum of American Art. pp. 4 –6. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ↑ "Welcome to the Amon Carter Press Room". Amon Carter Museum of American Art. pp. 1 –3. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ↑ Murray, Mary; et al. (2010). Look for Beauty: Philip Johnson and Art Museum Design. Utica, New York: Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute. p. 29. ISBN 0-915895-37-4.

- ↑ Murray, Mary; et al. (2010). Look for Beauty: Philip Johnson and Art Museum Design. Utica, New York: Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute. pp. 7–16. ISBN 0-915895-37-4.

- ↑ Wright, George (1997). Monument for a City: Philip Johnson's Design for the Amon Carter Museum. Fort Worth: Amon Carter Museum. p. 5. ISBN 0-88360-088-9.

- ↑ Wright, George (1997). Monument for a City: Philip Johnson's Design for the Amon Carter Museum. Fort Worth: Amon Carter Museum. p. 8. ISBN 0-88360-088-9.

- ↑ "Portico on a Plaza". Architectural Forum. March 1961.

- ↑ "Everything's Up to Date in Texas...But Me". Harper's. May 1961.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Murray, Mary; et al. (2010). Look for Beauty: Philip Johnson and Art Museum Design. Utica, New York: Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute. p. 33. ISBN 0-915895-37-4.

- 1 2 Wright, George (1997). Monument for a City: Philip Johnson's Design for the Amon Carter Museum. Fort Worth: Amon Carter Museum. p. 16. ISBN 0-88360-088-9.

- ↑ Junker Patricia; et al. (2001). An American Collection: Works from the Amon Carter Museum. New York: Hudson Hills Press in association with the Amon Carter Museum. p. 18. ISBN 1-55595-198-8.

External links

Media related to Amon Carter Museum at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Amon Carter Museum at Wikimedia Commons- Official website

- Search the ACMAA Art Collection

- Search the ACMAA Library Catalog

- View the ACMAA Art Collection in Google Art Project

- ACMAA in The Handbook of Texas Online

- ACMAA Exhibitions History

- ACMAA Publications History

Coordinates: 32°44′53″N 97°22′08″W / 32.748°N 97.369°W