Arethas of Caesarea

| Arethas of Caesarea | |

|---|---|

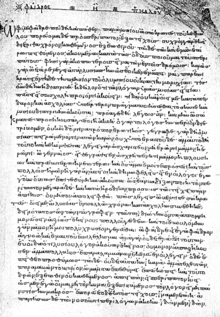

A portion of Plato's Phaedrus from the Codex Clarkianus believed to have been commissioned by Arethas of Caesarea (from the Bodleian Library Collection | |

| Born |

c. 860 AD Patrae |

| Died | c. 939 AD |

| Era | Macedonian Renaissance |

| Region | Byzantine Empire |

| School | Greek commentaries |

Main interests | Patristic Theology, Christian Eschatology, Christian theology, Stoicism, The reproduction and preservation of ancient texts |

|

Influences

| |

|

Influenced

| |

Arethas of Caesarea (Greek: Ἀρέθας; born c. 860 AD) was Archbishop of Caesarea in Cappadocia (modern Kayseri, Turkey) early in the 10th century, and is considered one of the most scholarly theologians of the Greek Orthodox Church. The codices produced by him, containing his commentaries are credited with preserving many ancient texts, including those of Plato and Marcus Aurelius' "Meditations".[1][2]

Life

He was born at Patrae (modern-day Greece). He was a disciple of Photius. He studied at the University of Constantinople. He became Deacon of Patrea around 900 and was made Archbishop of Caesarea by Nikolas of Constantinople in 903.[3] He was deeply involved in court politics and was a principle actor in the controversy over the scandal created when Emperor Leo VI attempted to marry a fourth time after his first three wives had died and left him without an heir.[4] Despite Arethas' fame as a scholar, Jenkins thinks little of him as a person. When recounting the details of the scandal, Arethas is described as "...narrow-minded, bad-hearted... morbidly ambitious and absolutely unscrupulous..."[5]

Works

He is the compiler of a Greek commentary (scholia) on the Apocalypse, for which he made considerable use of the similar work of his predecessor, Andrew of Caesarea. It was first printed in 1535 as an appendix to the works of Oecumenius.[6] Ehrhard inclines to the opinion that he wrote other scriptural commentaries. To his interest in the earliest Christian literature, caught perhaps from the above-named Andrew, we owe the Arethas Codex,[7] through which the texts of almost all of the ante-Nicene Greek Christian apologists have, in great measure, reached us.[8]

He is also known as a commentator of Plato and Lucian; the famous manuscript of Plato (Codex Clarkianus), taken from Patmos to London, was copied by order of Arethas. Other important Greek manuscripts, e.g. of Euclid,[9] the rhetor Aristides, and perhaps of Dio Chrysostom, are owing to him. Not a few of his minor writings, contained in a Moscow manuscript, are said still to await an editor.[10] Krumbacher emphasizes his fondness for ancient classical Greek literature and the original sources of Christian theology, in spite of the fact that he lived in a "dark" century, and was far away from any of the few remaining centers of erudition.

Arethas' works are also the earliest surviving ones that make concrete references as to the existence of the Meditations (written c. 175 AD) of the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius, which Arethas admits to holding in high personal favor in his letters to the Byzantine emperor Leo VI the Wise and his books (Scholia to Lucian and Scholia to Dio Chrysostom). Arethas is considered to be the individual responsible for reintroducing the Meditations into public discourse.

Notes

- ↑ Hadot, Pierre (1998). The Inner Citadel The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius (Translated by Michael Chase). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 24.

- ↑ Novotny 1977, p. 282-283.

- ↑ Jenkins, Romilly (1987). Byzantium: The Imperial Centuries Ad 610-1071. Canada: University of Toronto Press. pp. 219–229.

- ↑ Jenkins, p. 220-226.

- ↑ Jenkins, p. 219.

- ↑ It is found in P.G., CVI, 493.

- ↑ Paris, Gr. 451.

- ↑ Otto Bardenhewer, Patrologie, 40.

- ↑ L.D. Reynolds and Nigel G. Wilson, Scribes and Scholars 2nd. ed. (Oxford, 1974) p. 57

- ↑ See P.G., loc. cit., 787.

References

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "article name needed". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "article name needed". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton.

External links

Sources

- Novotny, Frantisek (1977). The Posthumous Life of Plato. The Hague: Springer Science & Business Media, Dec 6, 2012.