Atri, Abruzzo

| Atri | ||

|---|---|---|

| Comune | ||

| Comune di Atri | ||

|

Atri Cathedral | ||

| ||

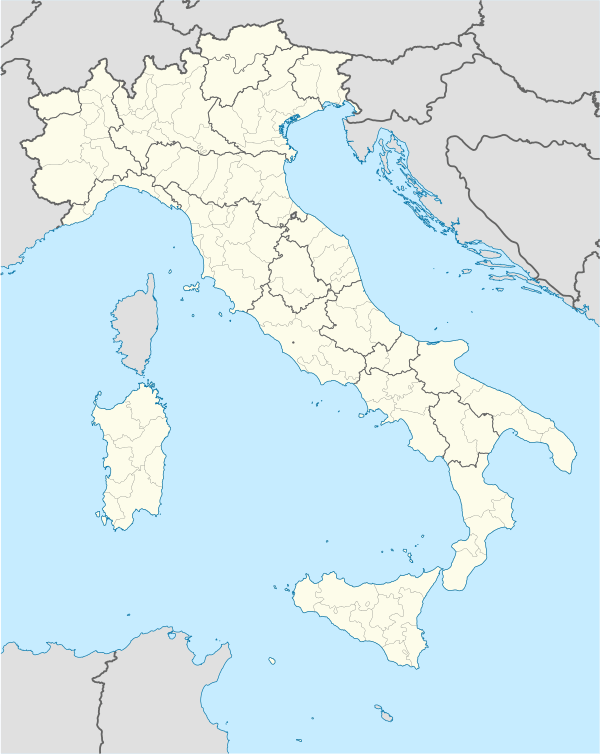

Atri Location of Atri in Italy | ||

| Coordinates: 42°35′N 13°59′E / 42.583°N 13.983°E | ||

| Country | Italy | |

| Region | Abruzzo | |

| Province / Metropolitan city | Teramo (TE) | |

| Frazioni | Casoli, Fontanelle, S. Margherita, S. Giacomo, Treciminiere | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Gabriele Astolfi (Centre-Right) | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 92.29 km2 (35.63 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 442 m (1,450 ft) | |

| Population (31 December 2010) | ||

| • Total | 11,239 | |

| • Density | 120/km2 (320/sq mi) | |

| Demonym(s) | Atriani | |

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | |

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | |

| Postal code | 64032 | |

| Dialing code | 085 | |

| Patron saint | Santa Reparata di Cesarea di Palestina | |

| Saint day | Eight days after Easter | |

| Website | Official website | |

Atri (Greek: Ἀδρία or Ἀτρία; Latin: Adria, Atria, Hadria, or Hatria) is a comune in the Province of Teramo in the Abruzzo region of Italy. In 2001, it had a population of over 11,500. Atri is the setting of the poem, The Bell of Atri, by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Its name is the origin of the name of the Emperor Hadrian.

History

Ancient Adria was a city of Picenum, situated about 10 kilometres (6 mi) from the Adriatic Sea, between the rivers Vomanus (modern Vomano) and Matrinus (modern Piomba). According to the Antonine Itinerary, it was distant 15 Roman miles from Castrum Novum (modern Giulianova) and 14 from Teate (modern Chieti).[1] It has been supposed, with much probability, to be of Etruscan origin, and a colony from the more celebrated city of the name, now Adria in the Veneto region,[2] though there is no historical evidence of the fact.

The city was founded by Greeks[3] from Aegina and reestablished[4] by Dionysius[5] I the tyrant of Syracuse in the 4th century BC.

The first certain historical notice of Adria is the establishment of a Roman colony there about 282 BCE.[6] In the early part of the Second Punic War (217 BCE) its territory was ravaged by Hannibal; but notwithstanding this calamity, it was one of the 18 Latin colonies which, in 209 BCE, were faithful to the cause of Rome, and willing to continue their contributions both of men and money.[7] At a later period, according to the Liber de Coloniis, it must have received a fresh colony, probably under Augustus: hence it is termed a Colonia, both by Pliny and in inscriptions. One of these gives it the titles of Colonia Aelia Hadria, whence it would appear that it had been re-established by the emperor Hadrian, whose family was originally derived from hence, though he was himself a native of Spain.[8]

The territory of Adria (ager Adrianus), though subsequently included in Picenum, appears to have originally formed a separate and independent district, bounded on the north by the river Vomanus (Vomano), and on the south by the Matrinus (la Piomba); at the mouth of this latter river was a town bearing the name of Matrinum, which served as the port of Adria; the city itself stood on a hill a few miles inland, on the same site still occupied by the modern Atri, a place of some consideration, with the title of a city, and the see of a bishop. Great part of the circuit of the ancient walls may be still traced, and mosaic pavements and other remains of buildings are also preserved.[9] According to the Antonine Itinerary[10] Adria (which may have been the original terminus of the Via Caecilia), was the point of junction of the Via Salaria and Via Valeria, a circumstance which probably contributed to its importance and flourishing condition under the Roman Empire.

After the fall of Rome, the region was subjected, along with most of northern and central Italy, to a long period of violent conflict. Ultimately, in the 6th century, the Lombards succeeded in establishing hegemony over the area, and Atri and other parts of Abruzzo found themselves annexed to the Duchy of Spoleto. The Lombards were displaced by the Normans, whose noble House of Acquaviva family ruled the town for decades from about 1393,[11] before merging their lands into the Kingdom of Naples, but remaining dominant in the city as Dukes of Atri until the 19th century. The rule of the Acquaivivas marked the highpoint of Atri's greatest power and splendor.

Ancient coinage

It is now generally admitted that the coins of Adria (with the legend "HAT.") belong to the city of Picenum, not that of the Veneto; but great difference of opinion has been entertained as to their age. They belong to the class commonly known as aes grave, and are even among the heaviest specimens known, exceeding in weight the most ancient Roman aeses. On this account they have been assigned to a very remote antiquity, some referring them to the Etruscan, others to the Greek, settlers. But there seems much reason to believe that they are not really so ancient, and belong, in fact, to the Roman colony, which was founded previous to the general reduction of the Italian brass coinage.[12]

Name

Some historians say that the city was founded by the Illyrians in the eleventh century BCE. They think that the city Atri was named after the Illyrian god Hatranus (Hatrani). The ancient name has been also described as the source from which the Adriatic Sea derived its name. Others maintain that the sea was named for Adria, an Etruscan city in Veneto region.

Main sights

- Duomo or Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta: This 13th century church was built on the remains of an earlier Romanesque structure. The cathedral incorporates a 56-metre (184 ft) high campanile, or bell tower, and a cloister. It houses a fresco cycle by the 15th-century Abruzzi painter Andrea de Litio (or Delitio). The Diocesian museum is located adjacent to cathedral. The crypt was originally a large Roman cistern; another forms the foundation of the ducal palace; and in the eastern portion of the town there is a complicated system of underground passages for collecting and storing water.

- Palazzo Ducale of Atri: Palace of the Duke of Acquaviva, built on the highest point in the city. The Palazzo now houses offices of both the municipal and provincial (Teramo) governments.

- Medieval Walls and Gates: The three remaining gates in the walls are the Porta Macelli, the Porta San Domenico, and the Capo d'Atri.

- Museo Capitolare

- San Francesco: This church features a flight of stairs in the Baroque style.

- San Domenico: This church contains two 17th-century paintings by Giacomo Farelli.

- Sant'Agostino: 14th-century church.

- San Nicola

- Santa Chiara: 13th-century church.

- Santo Spirito: 12th to 18th century church.

- Sant'Andrea Apostolo: 14th century church.

- Fonte Pila and the Fonte della Strega.

- Roman Theater: These ruins still contain unexplored grottoes.

- Belvedere of Viale Vomano and of the public park "Villa Comunale dei Cappuccini di Atri" offer panoramas of the valleys and sea below.

Villa Comunale dei Cappuccini di Atri (Capuchin Friars's - Public park)

The municipal park of Atri is a green area of about 3 hectares (7 acres) close to the historic center. It was built on areas owned by the Duke and the canons of the cathedral, realized by Paul Odescalchi, bishop of Atri. It comprises artificial terraces (made before the Second World War) for about three hectares, in a pleasantly arid area.

The boulevards of the villa are about 600 metres (2,000 ft) long. The remaining viability inside of the park is closed to traffic, and it mainly comprises paths.

Very interesting are also the caves of the Villa Comunale, probably once used as stables by the Capuchin friars. Their origin, however, is expected to be much older, and, although there is now no connection to the historic center, it is probable that they were used to escape during pirate raids.

In the park, there are also many sports' facilities, such as the soccer field and basketball court.

Close to the beautiful lookout over the sea and all of the valleys of the Terre del Cerrano (from Roseto degli Abruzzi up to Silvi Marina), there is a spectacular liberty-styled fountain, considered the emblem of the Villa Comunale. By staying close to that area, do not forget to see the old Cedrus Libani tree, considered to be a 300-year-old plant.

The eastern side of the Belvedere is erected over large walls, the ruins of an ancient fortress, once the summer palace of the local bishops.

Another symbol of the villa, renovated in the 1930s in an Italian garden, is the formaggione (the big cheese), a cylindrically shaped hedge, comprising conifers, with four entrances (located at the cardinal points). It represents the Garden of Secrets, a recurring element in many gardens of the castles and the noble villas of Italy, especially between the late 1700s and the first half of the last century. The Villa Comunale, a municipal park, provides a place to stroll and to rest.

Twin towns

Conversano, Italy, since 17 June 2010

Conversano, Italy, since 17 June 2010 Nardò, Italy, since 17 June 2010

Nardò, Italy, since 17 June 2010

Notes

- ↑ smith 1854, p. 8 cites Itin. Ant. pp. 308, 310, 313; comp. Tab. Peut.

- ↑ smith 1854, p. 8 cites Mazocchi, Tab. Heracl. p. 532; Müiller, Etrusker, vol. i. p. 145.

- ↑ In An Inventory of Archaic and Classical Poleis by Mogens Herman,ISBN 0-19-814099-1,2004,Page 323,"... the face of the advancing Gauls. According to Strabo 8.6.16, Aiginetans founded a colony en ombrikois, probably archaeologically attested in Adria (no. 75).

- ↑ In An Inventory of Archaic and Classical Poleis by Mogens Herman,ISBN 0-19-814099-1,2004,page 325,In C4f Adria was, apparently, refounded by Dionysios I (Theopomp. fr. 128; Tzetzes ad Lycophr. 631; Etym. Magn. 1854-57). According to Just. Epit. ..."

- ↑ In An Inventory of Archaic and Classical Poleis by Mogens Herman,ISBN 0-19-814099-1,2004,Page 228,"Dionysios I founded Adranon (no. 6) (Diod. 14.37.5 (r399), probably Adria (no. 75), possibly Ankon (no. 76), certainly Issa (no. 81); cf. Stylianou (1998) ad 13.4-5 at p. 196, Lissos no. ..."

- ↑ smith 1854, p. 8 cites Livy Epit. xi.; Madvig, de Coloniis, p. 298.

- ↑ smith 1854, p. 8 cites Livy xxii. 9, xxvii. 10; Polybius iii. 88.

- ↑ smith 1854, p. 8 cites Lib. Colon. p. 227; Plin. H. N. iii. 13. s. 18; Orell. Inscr. no. 148, 3018; Gruter, p. 1022; August Wilhelm Zumpt, De Coloniis p. 349; Spartian. Hadrian. 1.; Victor, Epit. 14.

- ↑ smith 1854, p. 8 cites Strabo v. p. 241; Silius Italicus viii. 439; Ptolemy iii. 1. § 52; Mela, ii. 4; Romanelli, vol. iii. p. 307.

- ↑ smith 1854, p. 8 cites Romanelli, vol. iii. pp. 308, 310.

- ↑ Chisholm 1911, p. 877.

- ↑ smith 1854, p. 8 cites Eckhel, vol. i. p. 98; Müller, Etrusker, vol. i. p. 308; Böckh, Metrologie, p. 379; Mommsen, Das Römische Münzwesen, p. 231; James Millingen, Numismatique de l'Italie, p. 216.

References

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Atri". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 877.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Atri". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 877.

- Attribution

- Notizie degli scavi (1902), 3.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1854). "Adria". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. 1. London: John Murray. p. 8.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1854). "Adria". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. 1. London: John Murray. p. 8.