Ballot marking device

A ballot marking device (BMD) or vote recorder is a type of voting machine used by voters to record votes on physical ballots. In general, ballot marking devices neither store nor tabulate ballots, but only allow the voter to record votes on ballots that are then stored and tabulated elsewhere.

The first ballot marking device emerged in the late 19th century, but were only widely used starting in the 1960s. Today, electronic ballot markers (EBMs) have come into widespread use as assistive devices in the context of optical scan voting systems. In the context of paper ballots, pens and pencils are used to record votes on ballots, but they are general-purpose items.

History

The first ballot marking devices specifically designed for use in elections emerged in the late 19th century along with proposals to use various punched-card ballot forms. Kennedy Dougan filed for patents on a punched-card system using a ballot marking device in 1890.[1][2] Urban Iles filed a proposal for a more sophisticated system in 1892.[3] The patents for these machines suggest that their primary goal was to provide for mechanical vote tabulation while retaining paper ballots that could be used to verify the operation of the tabulator in the event of any question. The punched cards used by these early machines were not designed to be compatible with any other data processing equipment.

In 1937, Frank Carrell, working for IBM applied for a patent on a ballot marking device that recorded on standard punched cards. This was incorporated into a full-sized voting booth with voter interface that resembled a mechanical voting machine, but recording on ballot cards that could be tabulated on standard punched-card tabulating machines.[4]

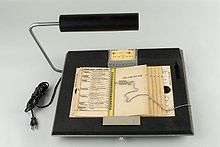

None of these machines was commercially successful. The first commercially successful ballot marking device was the Votomatic. This was based on the Port-A-Punch, a handheld device for recording data on pre-scored punched cards. Joseph Harris filed his first patent on what would become the Votomatic in 1962.[5]

Ballot cards punched on a Votomatic could be tabulated by standard punched card tabulating machines or sorted on card sorters. The machines cost only $185 each in 1965 dollars, and weighed only 6 pounds. This was one of the first machines to attract serious thinking about accessibility; John Ahmann filed for a patent on a punching stylus for the Votomatic adapted for use by voters with motor disabilities in 1986.[6] IBM marketed the Votomatic until 1968, when it spun off Computer Election Systems Inc. to produce and market the system. By 1980, the Votomatic system was used by over 29% of U.S. voters. By 1992, the Votomatic had replaced mechanical voting machines as the dominant voting system used in the United States. The dominance of the Votomatic ended abruptly following the Florida election recount of 2000.[7]

One of the major benefits of the Votomatic was that the machines were inexpensive enough that a polling place could have several machines, each with a ballot label printed in a different language. The needs of minority voters also drove the development of electronic voting in Belgium. In 1991, a Belgian, Julien Anno working with a group from Texas Instruments filed a patent application for an electronic ballot marker.[8] The Jites and Digivote systems used in Belgium are similar to this, although they use magnetic stripe cards instead of the bar codes used in the TI patent to record the ballot.[9] Belgium continues to use ballot marking devices, although the new machines use thermal printers to print human readable text along with a machine-readable bar code.

The AIS "Sailau" voting system developed in Belarus and Kazakhstan is conceptually similar to the Belgian system, except that it records votes on smart cards instead of bar codes or magnetic stripe cards.[10]

One weakness of punched card ballots is that, while voters can, in principle, verify that the punches on the ballots correspond to the choices the voter intended, this is difficult.[11] In the case of the Belgian magnetic-stripe cards and Kazakh smart cards, independent voter verification of the contents of the ballot card is impossible.

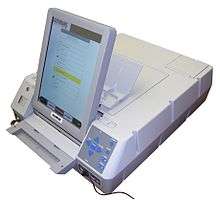

The passage of the Help America Vote Act in 2002 required new voting systems to be accessible. This led Eugene Cummings to file for a patent in 2003 on a machine that became the AutoMARK.[12] This machine has a touch screen, tactile keyboard, and headphone jack, as well as support for several other assistive devices, and it records votes on ballots used by several widely used optical scan voting systems.[13] By 2016, the AutoMARK was used statewide in 10 states in the United States, and widely used in 19 additional states.[14]

Sanford Morganstein also filed for a ballot-marking device patent in 2003, primarily motivated by the desire for a voter-verified paper audit trail.[15] Morganstein founded Populex Corporation to commercialize this system, and by 2004, the system was brought to market, certified to meet the 2002 Voting System Standards.[16] Like Julien Anno's ballot marking device proposal, the Populex system prints a compact summary ballot containing a bar code that is scanned as the voter drops the ballot in the ballot box. Unlike Anno's system, however, the Populex system also prints a human-readable summary on the ballot for voter verification. Morganstein's system never achieved deep market penetration, although it was used in Worth County, Missouri in 2012.[17]

Several other ballot marking devices have come on the market to compete with the AutoMARK. All of these print human readable content on paper ballots, but in several cases, these machines follow the Populex model by adding a machine-readable bar code. Voters cannot easily verify that the bar code matches the human-readable print, but in an audit, a hand count of the human-readable ballots can be compared with a machine count of the bar-coded content to verify that the electronic ballot marker was honest.

References

- ↑ Kennedy Dougan, Ballot-Holder, U.S. Patent 440,545, granted Nov. 11, 1890.

- ↑ Kennedy Dougan, Mechanical Ballot and Ballot-Holder, U.S. Patent 440,547, granted Nov. 11, 1890.

- ↑ Urban G. Iles, Ballot-Registering Device, U.S. Patent 500,001, granted June 20, 1893.

- ↑ Fred M. Carroll, Voting Machine, U.S. Patent 2,195,848, granted Apr. 2, 1940

- ↑ Joseph P. Harris, Data Registering Device, U.S. Patent 3,201,038, issued Aug. 17, 1965.

- ↑ John E. Ahmann, Punching Stylus for Handicapped Users, U.S. Patent 4,642,450, granted Feb. 10, 1987.

- ↑ Douglas W. Jones and Barbara Simons, Broken Ballots, CSLI Publications, 2012; see Sections 3.4-3.6, pages 48-55.

- ↑ Julien Anno, Russel Lewis, and Dale Cone, Method and System for Autonated Voting, U.S. Patent 5,189,288, issued Feb. 23, 1993.

- ↑ Expert Visit on New Voting Technologies, 8 October 2006 Local Elections, Kingdom of Belgium, OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights, Nov. 22, 2006.

- ↑ Douglas W. Jones, The Sailau E-Voting System, Direct Democracy: Progress and Pitfalls of Election Technology, Michael Yard, ed., International Foundation for Electoral Systems, Sept. 2010; pages 74-95.

- ↑ Douglas W. Jones and Barbara Simons, Broken Ballots, CSLI Publications, 2012; see Section 3.7, pages 55-57.

- ↑ Eugene Cummings, Ballot Marking System and Apparatus, U.S. Patent 7,080,779, issued Jul. 25, 2006.

- ↑ Douglas W. Jones and Barbara Simons, Broken Ballots, CSLI Publications, 2012; see Section 5.5, pages 111-115, and Section 9.3, pages 218-221.

- ↑ Election Systems and Software (ES&S) AutoMARK, Verified Voting, accessed Aug. 2016.

- ↑ Sanford J. Morganstein, Advanced Voting System and Method, U.S. Patent 7,284,700, issued Oct. 23, 2007.

- ↑ New Populex Voting Machine Receifes Federal Approval (press release), PR Newswire, Populex Corp, Dec. 16, 2004.

- ↑ PopulexSlate, Verified Voting, 2012.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ballot marking devices. |