Bonobo

| Bonobo[1] Temporal range: Early Pleistocene – Holocene | |

|---|---|

| | |

| Bonobo mother and daughter at the San Diego Zoo, 2006 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Genus: | Pan |

| Species: | P. paniscus |

| Binomial name | |

| Pan paniscus Schwarz, 1929 | |

| |

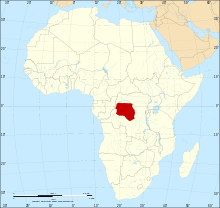

| Bonobo distribution | |

The bonobo (/bə.ˈnoʊ.boʊ/ or /ˈbɒ.nə.boʊ/; Pan paniscus), formerly called the pygmy chimpanzee and less often, the dwarf or gracile chimpanzee,[3] is an endangered great ape and one of the two species making up the genus Pan; the other is Pan troglodytes, or the common chimpanzee. Although the name "chimpanzee" is sometimes used to refer to both species together, it is usually understood as referring to the common chimpanzee, whereas Pan paniscus is usually referred to as the bonobo.[4]

The bonobo is distinguished by relatively long legs, pink lips, dark face and tail-tuft through adulthood, and parted long hair on its head. The bonobo is found in a 500,000 km2 (190,000 sq mi) area of the Congo Basin in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Central Africa. The species is omnivorous and inhabits primary and secondary forests, including seasonally inundated swamp forests. Political instability in the region and the timidity of bonobos has meant there has been relatively little field work done observing the species in its natural habitat.

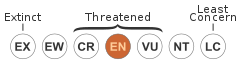

Along with the common chimpanzee, the bonobo is the closest extant relative to humans.[4] Because the two species are not proficient swimmers, the formation of the Congo River 1.5–2 million years ago possibly led to the speciation of the bonobo. Bonobos live south of the river, and thereby were separated from the ancestors of the common chimpanzee, which live north of the river. There is no concrete data on population numbers, but the estimate is between 29,500 and 50,000 individuals. The species is listed as Endangered on the IUCN Red List and is threatened by habitat destruction and human population growth and movement, though commercial poaching is the most prominent threat. They typically live 40 years in captivity;[5] their lifespan in the wild is unknown. As of June 2016 a total of 119 live in zoos across Europe; 65 distributed between six different German zoos, and a further 54 in zoos in Belgium, France, the Netherlands and England.

Etymology

Despite the alternative common name "pygmy chimpanzee", the bonobo is not especially diminutive when compared to the common chimpanzee. "Pygmy" may instead refer to the pygmy peoples who live in the same area.[6] The name "bonobo" first appeared in 1954, when Eduard Paul Tratz and Heinz Heck proposed it as a new and separate generic term for pygmy chimpanzees. The name is thought to be a misspelling on a shipping crate from the town of Bolobo on the Congo River, which was associated with the collection of chimps in the 1920s.[7][8] The term has also been reported as being a word for "ancestor" in an extinct Bantu language.[8]

Evolutionary history

Fossils

Fossils of Pan species were not described until 2005. Existing chimpanzee populations in West and Central Africa do not overlap with the major human fossil sites in East Africa. However, Pan fossils have now been reported from Kenya. This would indicate that both humans and members of the Pan clade were present in the East African Rift Valley during the Middle Pleistocene.[9] According to A. Zihlman, bonobo body proportions closely resemble those of Australopithecus,[10] leading evolutionary biologists like Jeremy Griffith to suggest that bonobos may be a living example of our distant human ancestors.[11]

Taxonomy and phylogeny

German anatomist Ernst Schwarz is credited with being the first Westerner to recognise the bonobo as being distinctive, in 1928, based on his analysis of a skull in the Tervuren museum in Belgium that previously had been thought to have belonged to a juvenile chimpanzee. Schwarz published his findings in 1929.[12][13] In 1933, American anatomist Harold Coolidge offered a more detailed description of the bonobo, and elevated it to species status.[13][14] The American psychologist and primatologist Robert Yerkes was also one of the first scientists to notice major differences between bonobos and chimpanzees.[15] These were first discussed in detail in a study by Eduard Paul Tratz and Heinz Heck published in the early 1950s.[16]

The first official publication of the sequencing and assembly of the bonobo genome became publicly available in June 2012. It was deposited with the International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank) under the EMBL accession number AJFE01000000[17] after a previous analysis by the National Human Genome Research Institute confirmed that the bonobo genome is about 0.4% divergent from the chimpanzee genome.[18] In addition, as of 2011 Svante Pääbo's group at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology were sequencing the genome of a female bonobo from the Leipzig zoo.[18]

Initial genetic studies characterised the DNA of chimpanzees and bonobos as being 98% to 99.4% identical to that of Homo sapiens.[19] Later studies showed that chimpanzees and bonobos are more closely related to humans than to gorillas.[20] In the crucial Nature paper reporting on initial genome comparisons, researchers identified 35 million single-nucleotide changes, five million insertion or deletion events, and a number of chromosomal rearrangements which constituted the genetic differences between the two Pan species and humans, covering 98% of the same genes.[21] While many of these analyses have been performed on the common chimpanzee rather than the bonobo, the differences between the two Pan species are unlikely to be substantial enough to affect the Pan-Homo comparison significantly.

There still is controversy, however. Scientists such as Jared Diamond in The Third Chimpanzee, and Morris Goodman[22] of Wayne State University in Detroit suggest that the bonobo and common chimpanzee are so closely related to humans that their genus name also should be classified with the human genus Homo: Homo paniscus, Homo sylvestris, or Homo arboreus. An alternative philosophy suggests that the term Homo sapiens is the misnomer rather, and that humans should be reclassified as Pan sapiens, though this would violate the Principle of Priority, as Homo was named before Pan (1758 for the former, 1816 for the latter). In either case, a name change of the genus would have implications on the taxonomy of extinct species closely related to humans, including Australopithecus. The current line between Homo and non-Homo species is drawn about 2.5 million years ago, and chimpanzee and human ancestry converge only about 7 million years ago, nearly three times longer.

DNA evidence suggests the bonobo and common chimpanzee species effectively separated from each other fewer than one million years ago.[23][24] The Pan line split from the last common ancestor shared with humans approximately six to seven million years ago. Because no species other than Homo sapiens has survived from the human line of that branching, both Pan species are the closest living relatives of humans and cladistically are equally close to humans. The recent genome data confirms the genetic equidistance.

Description

| NCBI genome ID | 10729 |

|---|---|

| Ploidy | diploid |

| Genome size | 2,869.21 Mb |

| Number of chromosomes | 24 pairs |

| Year of completion | 2012 |

The bonobo is commonly considered to be more gracile than the common chimpanzee. Although large male chimpanzees can exceed any bonobo in bulk and weight, the two species actually broadly overlap in body size. Adult female bonobos are somewhat smaller than adult males. Body mass in males ranges from 34 to 60 kg (75 to 132 lb), against an average of 30 kg (66 lb) in females. The total length of bonobos (from the nose to the rump while on all fours) is 70 to 83 cm (28 to 33 in).[25][26][27][28] When adult bonobos and chimpanzees stand up on their legs, they can both attain a height of 115 cm (45 in).[29] The bonobo's head is relatively smaller than that of the common chimpanzee with less prominent brow ridges above the eyes. It has a black face with pink lips, small ears, wide nostrils, and long hair on its head that forms a parting. Females have slightly more prominent breasts, in contrast to the flat breasts of other female apes, although not so prominent as those of humans. The bonobo also has a slim upper body, narrow shoulders, thin neck, and long legs when compared to the common chimpanzee.

Bonobos are both terrestrial and arboreal. Most ground locomotion is characterized by quadrupedal knuckle walking. Bipedal walking has been recorded as less than 1% of terrestrial locomotion in the wild, a figure that decreased with habituation,[30] while in captivity there is a wide variation. Bipedal walking in captivity, as a percentage of bipedal plus quadrupedal locomotion bouts, has been observed from 3.9% for spontaneous bouts to nearly 19% when abundant food is provided.[31] These physical characteristics and its posture give the bonobo an appearance more closely resembling that of humans than that of the common chimpanzee. The bonobo also has highly individuated facial features,[32] as humans do, so that one individual may look significantly different from another, a characteristic adapted for visual facial recognition in social interaction.

Multivariate analysis has shown bonobos are more neotenized than the common chimpanzee, taking into account such features as the proportionately long torso length of the bonobo.[33] Other researchers challenged this conclusion.[34]

Behavior

General

Primatologist Frans de Waal states bonobos are capable of altruism, compassion, empathy, kindness, patience, and sensitivity,[3] and described "bonobo society" as a "gynecocracy".[35][lower-alpha 1] Primatologists who have studied bonobos in the wild have documented a wide range of behaviors, including aggressive behavior and more cyclic sexual behavior similar to chimpanzees, even though the fact remains that bonobos show more sexual behavior in a greater variety of relationships. An analysis of female bonding among wild bonobos by Takeshi Furuichi stresses female sexuality and shows how female bonobos spend much more time in estrus than female chimpanzees.[36] Some primatologists have argued that de Waal's data reflect only the behavior of captive bonobos, suggesting that wild bonobos show levels of aggression closer to what is found among chimpanzees. De Waal has responded that the contrast in temperament between bonobos and chimpanzees observed in captivity is meaningful, because it controls for the influence of environment. The two species behave quite differently even if kept under identical conditions.[37] A 2014 study also found bonobos to be less aggressive than chimpanzees, particularly eastern chimpanzees. The authors argued that the relative peacefulness of western chimpanzees and bonobos was primarily due to ecological factors.[38]

Social behavior

Most studies indicate that females have a higher social status in bonobo society.[4] Aggressive encounters between males and females are rare, and males are tolerant of infants and juveniles. A male derives his status from the status of his mother.[39] The mother–son bond often stays strong and continues throughout life. While social hierarchies do exist, and although the son of a high ranking female may outrank a lower female, rank plays a less prominent role than in other primate societies.[40]

Because of the promiscuous mating behavior of female bonobos, a male cannot be sure which offspring are his. As a result, the entirety of parental care in bonobos is assumed by the mothers.[41]

Bonobo party size tends to vary because the groups exhibit a fission–fusion pattern. A community of approximately 100 will split into small groups during the day while looking for food, and then will come back together to sleep. They sleep in nests that they construct in trees.

Sociosexual behaviour

Sexual activity generally plays a major role in bonobo society, being used as what some scientists perceive as a greeting, a means of forming social bonds, a means of conflict resolution, and postconflict reconciliation.[42][4] Bonobos are the only non-human animal to have been observed engaging in tongue kissing, and oral sex.[43] Bonobos and humans are the only primates to typically engage in face-to-face genital sex, although a pair of western gorillas has been photographed in this position.[44]

Bonobos do not form permanent monogamous sexual relationships with individual partners. They also do not seem to discriminate in their sexual behavior by sex or age, with the possible exception of abstaining from sexual activity between mothers and their adult sons. When bonobos come upon a new food source or feeding ground, the increased excitement will usually lead to communal sexual activity, presumably decreasing tension and encouraging peaceful feeding.[45] This quality is also described by Dr. Susan Block as "The Bonobo Way" in her book of the same title "The Bonobo Way: The Evolution of Peace Through Pleasure".[46]

Bonobo clitorises are larger and more externalized than in most mammals;[47] while the weight of a young adolescent female bonobo "is maybe half" that of a human teenager, she has a clitoris that is "three times bigger than the human equivalent, and visible enough to waggle unmistakably as she walks".[48] In scientific literature, the female–female behavior of bonobos pressing genitals together is often referred to as genito-genital (GG) rubbing,[45][49] which is the non-human analogue of tribadism, engaged in by human females. This sexual activity happens within the immediate female bonobo community and sometimes outside of it. Ethologist Jonathan Balcombe stated that female bonobos rub their clitorises together rapidly for ten to twenty seconds, and this behavior, "which may be repeated in rapid succession, is usually accompanied by grinding, shrieking, and clitoral engorgement"; he added that it is estimated that they engage in this practice "about once every two hours" on average.[47] Because bonobos occasionally copulate face-to-face, "evolutionary biologist Marlene Zuk has suggested that the position of the clitoris in bonobos and some other primates has evolved to maximize stimulation during sexual intercourse".[47] On the other hand, the frequency of face-to-face mating observed in zoos and sanctuaries is not reflected in the wild, and thus may be an artifact of captivity. The position of the clitoris may alternatively permit GG-rubbings, which has been hypothesized to function as a means for female bonobos to evaluate their intrasocial relationships.[50]

Bonobo males occasionally engage in various forms of male–male genital behavior,[45][51] which is the non-human analogue of frotting, engaged in by human males. In one form, two bonobo males hang from a tree limb face-to-face while penis fencing.[45][52] This also may occur when two males rub their penises together while in face-to-face position. Another form of genital interaction (rump rubbing) occurs to express reconciliation between two males after a conflict, when they stand back-to-back and rub their scrotal sacs together. Takayoshi Kano observed similar practices among bonobos in the natural habitat.

More often than the males, female bonobos engage in mutual genital behavior, possibly to bond socially with each other, thus forming a female nucleus of bonobo society. The bonding among females enables them to dominate most of the males. Although male bonobos are individually stronger, they cannot stand alone against a united group of females.[45] Adolescent females often leave their native community to join another community. This migration mixes the bonobo gene pools, providing genetic diversity. Sexual bonding with other females establishes these new females as members of the group.

Bonobo reproductive rates are no higher than those of the common chimpanzee.[45] During oestrus, females undergo a swelling of the perineal tissue lasting 10 to 20 days. Most matings occur during the maximum swelling. The gestation period is on average 240 days. Postpartum amenorrhea (absence of menstruation) lasts less than one year and a female may resume external signs of oestrus within a year of giving birth, though the female is probably not fertile at this point. Female bonobos carry and nurse their young for four years and give birth on average every 4.6 years.[6] Compared to common chimpanzees, bonobo females resume the genital swelling cycle much sooner after giving birth, enabling them to rejoin the sexual activities of their society. Also, bonobo females which are sterile or too young to reproduce still engage in sexual activity. Mothers will help their sons get more matings from females in estrus.[53] Adult male bonobos have sex with infants.[54] Frans de Waal, an ethologist who has studied bonobos, remarked, "A lot of the things we see, like pedophilia and homosexuality, may be leftovers that some now consider unacceptable in our particular society."[55]

It is unknown how the bonobo avoids simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) and its effects.[56]

Diet

The bonobo is an omnivorous frugivore; 57% of its diet is fruit, but this is supplemented with leaves, honey, eggs,[57] meat from small vertebrates such as anomalures, flying squirrels and duikers,[58] and invertebrates.[59] In some instances, bonobos have been shown to consume lower-order primates.[60] Some claim bonobos have also been known to practise cannibalism in captivity, a claim disputed by others.[61][62] However, at least one confirmed report of cannibalism in the wild of a deceased infant was described in 2008.[63][64]

Peacefulness

Observations in the wild indicate that the males among the related common chimpanzee communities are extraordinarily hostile to males from outside the community. Parties of males 'patrol' for the neighboring males that might be traveling alone, and attack those single males, often killing them.[65] This does not appear to be the behavior of bonobo males or females, which seem to prefer sexual contact over violent confrontation with outsiders.[4] In fact, the Japanese scientists who have spent the most time working with wild bonobos describe the species as extraordinarily peaceful, and de Waal has documented how bonobos may often resolve conflicts with sexual contact (hence the "make love, not war" characterization for the species). Between groups, social mingling may occur, in which members of different communities have sex and groom each other, behavior which is unheard of among common chimpanzees. Conflict is still possible between rival groups of bonobos, but no official scientific reports of it exist. The ranges of bonobos and chimpanzees are separated by the Congo River, with bonobos living to the south of it, and chimpanzees to the north.[66][67] It has been hypothesized that bonobos are able to live a more peaceful lifestyle in part because of an abundance of nutritious vegetation in their natural habitat, allowing them to travel and forage in large parties.[68]

Recent studies show that there are significant brain differences between bonobos and chimps. The brain anatomy of bonobos has more developed and larger regions assumed to be vital for feeling empathy, sensing distress in others and feeling anxiety, which makes them less aggressive and more empathic than their close relatives. They also have a thick connection between the amygdala, an important area that can spark aggression, and the ventral anterior cingulate cortex, which helps control impulses. This thicker connection may make them better at regulating their emotional impulses and behavior.[69]

Bonobo society is dominated by females, and severing the lifelong alliance between mothers and their male offspring may make them vulnerable to female aggression.[4] De Waal has warned of the danger of romanticizing bonobos: "All animals are competitive by nature and cooperative only under specific circumstances" and that "when first writing about their behaviour, I spoke of 'sex for peace' precisely because bonobos had plenty of conflicts. There would obviously be no need for peacemaking if they lived in perfect harmony."[70]

Surbeck and Hohmann showed in 2008 that bonobos sometimes do hunt monkey species. Five incidents were observed in a group of bonobos in Salonga National Park, which seemed to reflect deliberate cooperative hunting. On three occasions, the hunt was successful, and infant monkeys were captured and eaten.[60]

Similarity to humans

Bonobos are capable of passing the mirror-recognition test for self-awareness,[71] as are all great apes. They communicate primarily through vocal means, although the meanings of their vocalizations are not currently known. However, most humans do understand their facial expressions[19] and some of their natural hand gestures, such as their invitation to play. The communication system of wild bonobos includes a characteristic that was earlier only known in humans: bonobos use the same call to mean different things in different situations, and the other bonobos have to take the context into account when determining the meaning.[72] Two bonobos at the Great Ape Trust, Kanzi and Panbanisha, have been taught how to communicate using a keyboard labeled with lexigrams (geometric symbols) and they can respond to spoken sentences. Kanzi's vocabulary consists of more than 500 English words,[73] and he has comprehension of around 3,000 spoken English words.[74] Kanzi is also known for learning by observing people trying to teach his mother; Kanzi started doing the tasks that his mother was taught just by watching, some of which his mother had failed to learn. Some, such as philosopher and bioethicist Peter Singer, argue that these results qualify them for "rights to survival and life" — rights that humans theoretically accord to all persons. (See great ape personhood) Afterwards Kanzi was also taught how to use and create stone tools in 1990. Then, within 3 years, three researchers — Kathy Schick, Nicholas Toth and Gary Garufi — wanted to test Kanzi's knapping skills. Though Kanzi was able to form flake technology, he did not create it the way they expected. Unlike the way hominids did it, where they held the core in one hand and knapped it with the other, Kanzi threw the cobble against a hard surface or against another cobble. This allowed him to produce a larger force to initiate a fracture as opposed to knapping it in his hands.[75]

As in other great apes and humans, third party affiliation toward the victim – the affinitive contact made toward the recipient of an aggression by a group member other than the aggressor – is present in bonobos.[76] A 2013 study [77] found that both the affiliation spontaneously offered by a bystander to the victim and the affiliation requested by the victim (solicited affiliation) can reduce the probability of further aggression by group members on the victim (this fact supporting the Victim-Protection Hypothesis). Yet, only spontaneous affiliation reduced victim anxiety – measured via self-scratching rates – thus suggesting not only that non-solicited affiliation has a consolatory function but also that the spontaneous gesture – more than the protection itself – works in calming the distressed subject. The authors hypothesize that the victim may perceive the motivational autonomy of the bystander, who does not require an invitation to provide post-conflict affinitive contact. Moreover, spontaneous – but not solicited – third party affiliation was affected by the bond between consoler and victim (this supporting the Consolation Hypothesis). Importantly, spontaneous affiliation followed the empathic gradient described for humans, being mostly offered to kin, then friends, then acquaintances (these categories having been determined using affiliation rates between individuals). Hence, consolation in the bonobo may be an empathy-based phenomenon.

Instances in which non-human primates have expressed joy have been reported. One study analyzed and recorded sounds made by human infants and bonobos when they were tickled.[78] Although the bonobos' laugh was at a higher frequency, the laugh was found to follow a spectrographic pattern similar to that of human babies.[78]

Distribution and habitat

Bonobos are found only south of the Congo River and north of the Kasai River (a tributary of the Congo),[79] in the humid forests of the Democratic Republic of Congo of central Africa. Ernst Schwarz's 1927 paper “Le Chimpanzé de la Rive Gauche du Congo”, announcing his discovery, has been read as an association between the Parisian Left Bank and the left bank of the Congo River; the bohemian culture in Paris, and an unconventional ape in the Congo.[80]

Conservation status

The IUCN Red List classifies bonobos as an endangered species, with conservative population estimates ranging from 29,500 to 50,000 individuals.[2] Major threats to bonobo populations include habitat loss and hunting for bushmeat, the latter activity having increased dramatically during the first and second Congo wars in the Democratic Republic of Congo due to the presence of heavily armed militias even in remote "protected" areas such as Salonga National Park. This is part of a more general trend of ape extinction.

As the bonobos' habitat is shared with people, the ultimate success of conservation efforts will rely on local and community involvement. The issue of parks versus people[81] is salient in the Cuvette Centrale the bonobos' range. There is strong local and broad-based Congolese resistance to establishing national parks, as indigenous communities have often been driven from their forest homes by the establishment of parks. In Salonga National Park, the only national park in the bonobo habitat, there is no local involvement, and surveys undertaken since 2000 indicate the bonobo, the African forest elephant, and other species have been severely devastated by poachers and the thriving bushmeat trade.[82] In contrast, areas exist where the bonobo and biodiversity still thrive without any established parks, due to the indigenous beliefs and taboos against killing bonobos.

During the wars in the 1990s, researchers and international non-governmental organizations (NGOs) were driven out of the bonobo habitat. In 2002, the Bonobo Conservation Initiative initiated the Bonobo Peace Forest Project supported by the Global Conservation Fund of Conservation International and in cooperation with national institutions, local NGOs, and local communities. The Peace Forest Project works with local communities to establish a linked constellation of community-based reserves, managed by local and indigenous people. This model, implemented mainly through DRC organizations and local communities, has helped bring about agreements to protect over 50,000 square miles (130,000 km2) of the bonobo habitat. According to Dr. Amy Parish, the Bonobo Peace Forest "is going to be a model for conservation in the 21st century."[83]

The port town of Basankusu is situated on the Lulonga River, at the confluence of the Lopori and Maringa Rivers, in the north of the country, making it well placed to receive and transport local goods to the cities of Mbandaka and Kinshasa. With Basankusu being the last port of substance before the wilderness of the Lopori Basin and the Lomako River—–the bonobo heartland—conservation efforts for the bonobo[84] use the town as a base.[85][86]

In 1995, concern over declining numbers of bonobos in the wild led the Zoological Society of Milwaukee, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, with contributions from bonobo scientists around the world, to publish the Action Plan for Pan paniscus: A Report on Free Ranging Populations and Proposals for their Preservation. The Action Plan compiles population data on bonobos from 20 years of research conducted at various sites throughout the bonobo's range. The plan identifies priority actions for bonobo conservation and serves as a reference for developing conservation programs for researchers, government officials, and donor agencies.

Acting on Action Plan recommendations, the ZSM developed the Bonobo and Congo Biodiversity Initiative. This program includes habitat and rain-forest preservation, training for Congolese nationals and conservation institutions, wildlife population assessment and monitoring, and education. The Zoological Society has conducted regional surveys within the range of the bonobo in conjunction with training Congolese researchers in survey methodology and biodiversity monitoring. The Zoological Society’s initial goal was to survey Salonga National Park to determine the conservation status of the bonobo within the park and to provide financial and technical assistance to strengthen park protection. As the project has developed, the Zoological Society has become more involved in helping the Congolese living in bonobo habitat. The Zoological Society has built schools, hired teachers, provided some medicines, and started an agriculture project to help the Congolese learn to grow crops and depend less on hunting wild animals.[87]

With grants from the United Nations, USAID, the U.S. Embassy, the World Wildlife Fund, and many other groups and individuals, the Zoological Society also has been working to:

- Survey the bonobo population and its habitat to find ways to help protect these apes

- Develop antipoaching measures to help save apes, forest elephants, and other endangered animals in Congo's Salonga National Park, a UN World Heritage site

- Provide training, literacy education, agricultural techniques, schools, equipment, and jobs for Congolese living near bonobo habitats so that they will have a vested interest in protecting the great apes – the ZSM started an agriculture project to help the Congolese learn to grow crops and depend less on hunting wild animals.

- Model small-scale conservation methods that can be used throughout Congo

Starting in 2003, the U.S. government allocated $54 million to the Congo Basin Forest Partnership. This significant investment has triggered the involvement of international NGOs to establish bases in the region and work to develop bonobo conservation programs. This initiative should improve the likelihood of bonobo survival, but its success still may depend upon building greater involvement and capability in local and indigenous communities.[88]

The bonobo population is believed to have declined sharply in the last 30 years, though surveys have been hard to carry out in war-ravaged central Congo. Estimates range from 60,000 to fewer than 50,000 living, according to the World Wildlife Fund.

In addition, concerned parties have addressed the crisis on several science and ecological websites. Organizations such as the World Wide Fund for Nature, the African Wildlife Foundation, and others, are trying to focus attention on the extreme risk to the species. Some have suggested that a reserve be established in a more stable part of Africa, or on an island in a place such as Indonesia. Awareness is ever increasing, and even nonscientific or ecological sites have created various groups to collect donations to help with the conservation of this species.

See also

- Basankusu, DR Congo – base for bonobo research and conservation

- Bonobo Conservation Initiative

- Chimpanzee genome project

- Claudine André

- Great ape personhood

- Great Ape Project

- Kanzi – a captive bonobo who uses language

- List of apes – notable individual apes

- Lola ya Bonobo

Notes

- ↑ Gynecocracy, among people, 'women's government over women and men' or 'women's social supremacy'

References

- ↑ Groves, C.P. (2005). Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M., eds. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 183. OCLC 62265494. ISBN 0-801-88221-4.

- 1 2 Fruth, B.; Hickey, J. R.; André, C.; Furuichi, T.; Hart, J.; Hart, T.; Kuehl, H.; Maisels, F.; Nackoney, J.; Reinartz, G.; Sop, T.; Thompson, J.; Williamson, E. A. (2016). "Pan paniscus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2016: e.T15932A17964305. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- 1 2 de Waal, Frans; Lanting, Frans (1997). Bonobo: The Forgotten Ape. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20535-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Angier, Natalie (September 10, 2016). "Beware the Bonds of Female Bonobos". New York Times. Retrieved September 10, 2016.

- ↑ Rowe, N. (1996) Pictural Guide to the Living Primates, Pogonias Press, East Hampton, ISBN 0-9648825-1-5.

- 1 2 Williams, A.; Myers, P. (2004). "Pan paniscus". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 6 January 2012.

- ↑ Savage-Rumbaugh, Sue; Lewin, Roger (1994). Kanzi: the ape at the brink of the human mind. John Wiley & Sons. p. 97. ISBN 0-385-40332-1.

- 1 2 de Waal, Frans (2005). Our Inner Ape. Riverhead Books. ISBN 1-57322-312-3.

- ↑ McBrearty, Sally; Jablonski, Nina G. (1 September 2005). "First fossil chimpanzee". Nature. 437 (7055): 105–8. Bibcode:2005Natur.437..105M. doi:10.1038/nature04008. PMID 16136135.

- ↑ Zihlman, AL; Cronin, JE; Cramer, DL; Sarich, VM (1978). "Pygmy chimpanzee as a possible prototype for the common ancestor of humans, chimpanzees and gorillas". Nature. 275 (5682): 744–6. Bibcode:1978Natur.275..744Z. doi:10.1038/275744a0. PMID 703839.

- ↑ Griffith, Jeremy (2013). Freedom Book 1. Part 8:4G. WTM Publishing & Communications. ISBN 978-1-74129-011-0.

- ↑ Schwarz, Ernst (April 1, 1929). "Das Vorkommen des Schimpansen auf den linken Kongo-Ufer" (PDF). Revue de zoologie et de botanique africaines. 16: 425–426.

- 1 2 Coolidge, Harold Jefferson Jr. (July–September 1933). "Pan paniscus. Pigmy chimpanzee from south of the Congo river". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 18 (1): 1–59. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330180113. Coolidge's paper contains a translation of Schwarz's earlier report.

- ↑ Herzfeld, Chris (2007). "L'invention du bonobo" (PDF). Bulletin d'histoire et d'épistémologie des sciences de la vie (in French). 14 (2): 139–162. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ↑ Savage-Rumbaugh, Sue (21 June 2010). "Bonobos have a secret". New Scientist. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ↑ de Waal, Frans B. M. (2002). Tree of Origin: What Primate Behavior Can Tell Us About Human Social Evolution. Harvard University Press. p. 51. ISBN 0674010043.

- ↑ Prüfer, Kay et al. (2012) "The bonobo genome compared with the chimpanzee and human genomes". Nature doi:10.1038/nature11128 PMID 22722832

- 1 2 Karow, Julia (2008-05-13). "Neandertal, bonobo genomes may shed light on human evolution; MPI, 454 preparing drafts". In Sequence. Genome Web. Retrieved 2011-12-08.

- 1 2 "Colombus Zoo: Bonobo". Archived from the original on 2006-05-02. Retrieved 2006-08-01.

- ↑ Takahata, N.; Satta, Y.; Klein, J. (1995). "Divergence time and population size in the lineage leading to modern humans". Theoretical Population Biology. 48 (2): 198–221. doi:10.1006/tpbi.1995.1026. PMID 7482371.

- ↑ The Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium (1 September 2005). "Initial sequence of the chimpanzee genome and comparison with the human genome". Nature. 437 (7055): 69–87. Bibcode:2005Natur.437...69.. doi:10.1038/nature04072. PMID 16136131.

- ↑ Hecht, Jeff (19 May 2003). "Chimps are human, gene study implies". New Scientist. Retrieved 2011-12-08.

- ↑ Won, Yong-Jin; Hey, Jody (13 October 2004). "Divergence population genetics of chimpanzees". Molecular Biology & Evolution. 22 (2): 297–307. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi017. PMID 15483319.

- ↑ Fischer, Anne; Wiebe, Victor; Pääbo, Svante; Przeworski, Molly (12 February 2004). "Evidence for a complex demographic history of chimpanzees". Molecular Biology & Evolution. 21 (5): 799–808. doi:10.1093/molbev/msh083. PMID 14963091.

- ↑ Scholz, M. N.; d'Aout, K.; Bobbert, M. F.; Aerts, P. (2006). "Vertical jumping performance of bonobo (Pan paniscus) suggests superior muscle properties". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 273 (1598): 2177–2184. doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3568. PMC 1635523

. PMID 16901837.

. PMID 16901837. - ↑ "Bonobo videos, photos and facts – Pan paniscus". ARKive. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ↑ Burnie D and Wilson DE (Eds.) (2005) Animal: The Definitive Visual Guide to the World's Wildlife. DK Adult. ISBN 0789477645

- ↑ Novak, R. M. (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World. 6th edition. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, ISBN 0-8018-5789-9

- ↑ Shumaker, Robert W.; Walkup, Kristina R. and Beck, Benjamin B. (2011) Animal Tool Behavior: The Use and Manufacture of Tools by Animals, JHU Press, ISBN 1421401282.

- ↑ Doran, D. M. (1993). "Comparative locomotor behavior of chimpanzees and bonobos: the influence of morphology on locomotion". Am J Phys Anthropol. 91 (1): 83–98. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330910106. PMID 8512056.

- ↑ D’Août, K.; Vereecke, E.; Schoonaert, K.; De Clercq, D.; Van Elsacker, L.; Aerts, P. (2004). "Locomotion in bonobos (Pan paniscus): differences and similarities between bipedal and quadrupedal terrestrial walking, and a comparison with other locomotor modes". Journal of Anatomy. 204 (5): 353–361. doi:10.1111/j.0021-8782.2004.00292.x. PMC 1571309

. PMID 15198700.

. PMID 15198700. - ↑ Wilson Wiessner, Pauline and Schiefenhövel, Wulf (1996). Food and the Status Quest: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Berghahn Books. ISBN 1571818715. p. 50. "...twenty-two mature community members (eight males, fourteen females)could be identified using facial features...

- ↑ Shea, B.T. (1983). "Paedomorphosis and neoteny in the pygmy chimpanzee". Science. 222 (4623): 521–2. Bibcode:1983Sci...222..521S. doi:10.1126/science.6623093. PMID 6623093.

- ↑ Godfrey L; Sutherland M. (1996). "Paradox of peramophic paedomorphosis: heterochrony and human evolution". Am J Phys Anthropol. 99 (1): 17–42. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330990102. PMID 8928718.

- ↑ de Waal, Frans (2013). The Bonobo and the Atheist: In Search of Humanism Among the Primates (1st ed.). W. W. Norton. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-393-07377-5.

- ↑ Furuichi, T (2011). "Female contributions to the peaceful nature of bonobo society". Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews. 20 (4): 131–42. doi:10.1002/evan.20308. PMID 22038769.

- ↑ Stanford, C. B. (1998). "The Social Behavior of Chimpanzees and Bonobos: Empirical Evidence and Shifting Assumptions". Current Anthropology. 39 (4): 399–420. doi:10.1086/204757.

- ↑ Wilson, M. L.; Boesch, C.; Fruth, B.; Furuichi, T.; Gilby, I. C.; Hashimoto, C.; Hobaiter, C. L.; Hohmann, G.; Itoh, N.; Koops, K.; Lloyd, J. N.; Matsuzawa, T.; Mitani, J. C.; Mjungu, D. C.; Morgan, D.; Muller, M. N.; Mundry, R.; Nakamura, M.; Pruetz, J.; Pusey, A. E.; Riedel, J.; Sanz, C.; Schel, A. M.; Simmons, N.; Waller, M.; Watts, D. P.; White, F.; Wittig, R. M.; Zuberbühler, K.; Wrangham, R. W. (2014). "Lethal aggression in Pan is better explained by adaptive strategies than human impacts". Nature. 513 (7518): 414–7. Bibcode:2014Natur.513..414W. doi:10.1038/nature13727. PMID 25230664.

- ↑ White F. (1996) "Comparative socio-ecology of Pan paniscus", pp. 29–41 in: McGrew WC, Marchant LF, Nishida T (eds.) Great ape societies. Cambridge, England: Cambridge Univ Press, ISBN 0521555361.

- ↑ Henry Nicholls. 17 March 2016. Do bonobos really spend all their time having sex?. BBC

- ↑ Cawthon Lang KA. (December 2010) Primate Factsheets: Bonobo (Pan paniscus) behavior. University of Wisconsin

- ↑ Aggression topics. University of New Hampshire

- ↑ Manson, J.H.; Perry, S.; Parish, A.R. (1997). "Nonconceptive Sexual Behavior in Bonobos and Capuchins". International Journal of Primatology. 18 (5): 767–86. doi:10.1023/A:1026395829818.

- ↑ Nguyen, Tuan C. (2008-02-13). "Gorillas Caught in Very Human Act". Live Science

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 de Waal, Frans B. M. (March 1995). "Bonobo Sex and Society" (PDF). Scientific American. 272 (3): 58–64. Bibcode:1995SciAm.272c..82W. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0395-82. PMID 7871411. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ↑ Block, Susan (2014) The Bonobo Way: The Evolution of Peace Through Pleasure Paperback. Gardner & Daughters Publishers. ISBN 0692323767

- 1 2 3 Balcombe, Jonathan Peter (2011). The Exultant Ark: A Pictorial Tour of Animal Pleasure. University of California Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-520-26024-5. Retrieved 2012-11-22.

- ↑ Angier, Natalie (1999). Woman: An Intimate Geography. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-395-69130-4. Retrieved 2012-11-22.

- ↑ Paoli, T.; Palagi, E.; Tacconi, G.; Tarli, S. B. (2006). "Perineal swelling, intermenstrual cycle, and female sexual behavior in bonobos (Pan paniscus)". American Journal of Primatology. 68 (4): 333–347. doi:10.1002/ajp.20228. PMID 16534808.

- ↑ Hohmann, G.; Fruth, B. (2000). "Use and function of genital contacts among female bonobos". Animal Behaviour. 60 (1): 107–120. doi:10.1006/anbe.2000.1451.

- ↑ "Courtney Laird, "Social Organization"". Bio.davidson.edu. 2004. Archived from the original on 2011-05-19. Retrieved 2009-07-03.

- ↑ Frans B. M. de Waal (2001). "Bonobos and Fig Leaves". The ape and the sushi master : cultural reflections by a primatologist. Basic Books. ISBN 84-493-1325-2.

- ↑ Henry Nicholls. 17 March 2016. Do bonobos really spend all their time having sex?. BBC

- ↑ de Waal, F. B. M. (1990). "Sociosexual behavior used for tension regulation in all age and sex combinations among bonobos", pp. 378–393 in Pedophilia: Biosocial Dimensions, J. R. Feierman (ed.). Springer, New York. ISBN 9781461396840

- ↑ Casual Sex Play Common Among Bonobos. Discover, June 1992

- ↑ Paul M. Sharp; George M. Shaw; Beatrice H. Hahn (2005). "Simian Immunodeficiency Virus Infection of Chimpanzees". Journal of Virology. 79 (7): 3891–3902. doi:10.1128/jvi.79.7.3891-3902.2005. PMID 15767392.

- ↑ Cawthorn Lang, Kristina (2011). "Bonobo: Pan paniscus". National Primate Research Center, University of Wisconsin – Madison.

- ↑ Ihobe H (1992). "Observations on the meat-eating behavior of wild bonobos (Pan paniscus) at Wamba, Republic of Zaire". Primates (journal). 33 (2): 247–250. doi:10.1007/BF02382754.

- ↑ Rafert, J. and E.O. Vineberg (1997). "Bonobo Nutrition – relation of captive diet to wild diet," Bonobo Husbandry Manual, American Association of Zoos and Aquariums

- 1 2 Surbeck M; Fowler A; Deimel C; Hohmann G (2008). "Evidence for the consumption of arboreal, diurnal primates by bonobos (Pan paniscus)". American Journal of Primatology. 71 (2): 171–4. doi:10.1002/ajp.20634. PMID 19058132.; Surbeck M; Hohmann G (2008). "Primate hunting by bonobos at LuiKotale, Salonga National Park". Current Biology. 18 (19): R906–7. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.08.040. PMID 18957233.

- ↑ Parker, Ian (2007-07-30). "Swingers". Our Far-Flung Correspondents. The New Yorker. Retrieved 2011-12-08.

- ↑ de Waal, Frans (2009-10-18). "Was "Ardi" a Liberal?". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ↑ Walker, Matt (2010-02-01). "Wild bonobo mother ape eats own infant in DR Congo". BBC News.

- ↑ Hippy apes caught cannibalising their young. New Scientist (1 February 2010). Retrieved on 2013-04-18.

- ↑ "Chimpanzee behavior: Killer instincts". The Economist. June 24, 2010. Retrieved 2011-12-08.

- ↑ Raffaele, Paul (November 2006) The Smart and Swinging Bonobo. Smithsonian Magazine.

- ↑ Caswell JL; Mallick S; Richter DJ (2008). McVean, Gil, ed. "Analysis of Chimpanzee History Based on Genome Sequence Alignments". PLoS Genet. 4 (4): e1000057. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000057. PMC 2278377

. PMID 18421364.

. PMID 18421364. - ↑ White, Frances J.; Wrangham, Richard W. (1988). "Feeding competition and patch size in the chimpanzee species Pan paniscus and Pan troglodytes". Behaviour. 105: 148–164. doi:10.1163/156853988X00494. JSTOR 4534684.

- ↑ Brain differences may explain varying behavior of bonobos and chimpanzees. Washingtonpost.com (2011-04-12). Retrieved on 2012-12-26.

- ↑ de Waal, Frans (August 8, 2007). "Bonobos, Left & Right". Skeptic.

- ↑ Best, Steven (Spring 2009). "Minding the Animals: Ethology and the Obsolescence of Left Humanism". The International Journal of Inclusive Democracy. 5 (2). Retrieved 2012-02-08.

- ↑ "Bonobo squeaks hint at earlier speech evolution". BBC News. August 4, 2015. Retrieved 2015-08-05.

- ↑ "Meet our Great Apes: Kanzi". Archived from the original on 2008-06-30. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- ↑ Raffaele, P. (2006). "Speaking Bonobo". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- ↑ Schick, Kathy; Toth, Nicholas; Garufi, Gary; Savage-Rumbaugh, E.Sue; Rumbaugh, Duane; Sevcik, Rose (1999). "Continuing Investigations into the Stone Tool-making and Tool-using Capabilities of a Bonobo (Pan paniscus)". Journal of Archaeological Science. 26 (7): 821–832. doi:10.1006/jasc.1998.0350.

- ↑ Palagi E; Paoli; Tarli (2004). "Reconciliation and consolation in captive bonobos (Pan paniscus)". Am J Primatol. 62 (1): 15–30. doi:10.1002/ajp.20000. PMID 14752810.

- ↑ Palagi E; Norscia I (2013). "Bonobos Protect and Console Friends and Kin". PLoS ONE. 8 (11): e79290. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...879290P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0079290. PMC 3818457

. PMID 24223924.

. PMID 24223924. - 1 2 Beale, B. (2003). "Where Did Laughter Come From?". ABC Science Online. Retrieved 2008-08-10.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (2004). "Chimpanzees". The Ancestor's Tale. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 1-155-16265-X.

- ↑ Quammen, David. "The Left Bank Ape". The New Age of Exploration, 2013. National Geographic. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- ↑ Reid, John (2006-06-15). Parks and people, not parks vs. people, San Francisco Chronicle.

- ↑ Bonobo and large mammal survey Archived May 6, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.. Zoological Society of Milwaukee.

- ↑ The Make Love, Not War Species, Living on Earth, (July 2006), National Public Radio

- ↑ Hart, Therese (2012-07-27) Searching for Bonobo in Congo. Bonoboincongo.com. Retrieved on 2012-12-26.

- ↑ Lola Ya Bonobo (Bonobo Heaven). Lolayabonobo.wildlifedirect.org. Retrieved on 2012-12-26.

- ↑ Bonobo Reintroduction in the Democratic Republic of Congo. friendsofbonobos.org (November 2009) . Retrieved on 2012-12-26.

- ↑ "Bonobo and Congo Biodiversity Initiative". Zoological Society of Milwaukee.

- ↑ Chapin, Mac, (November/December 2004), Vision for a Sustainable World, WORLDWATCH magazine

Further reading

Books

- de Waal, Frans, and Frans Lanting, Bonobo: The Forgotten Ape, University of California Press, 1997. ISBN 0-520-20535-9; ISBN 0-520-21651-2 (trade paperback)

- Kano, Takayoshi, The Last Ape: Pygmy Chimpanzee Behavior and Ecology, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1992.

- Savage-Rumbaugh, Sue, and Roger Lewin, Kanzi: The Ape at the Brink of the Human Mind, John Wiley, 1994. ISBN 0-471-58591-2; ISBN 0-471-15959-X (trade paperback)

- Woods, Vanessa, Bonobo Handshake, Gotham Books, 2010. ISBN 978-1-59240-546-6

- Sandin, Jo, Bonobos: Encounters in Empathy, Zoological Society of Milwaukee & The Foundation for Wildlife Conservation, Inc., 2007. ISBN 978-0-9794151-0-4

- de Waal, Frans, The Bonobo and the Atheist, Norton, 2013. ISBN 978-0393073775

Articles

- de Waal, Frans, "Bonobo: Sex & Society", Scientific American, 1995

- DeBartolo, Anthony. "The Bonobo: 'Newest' apes are teaching us about ourselves", Chicago Tribune June 11, 1998.

- Schweller, Ken, "Apes With Apps," IEEE Spectrum Magazine, July 2012.

- Madrigal, Alexis "Brian the Mentally Ill Bonobo, and How He Healed", The Atlantic, June 11, 2014.

- Parker, Ian "Swingers", The New Yorker, July 30, 2007.

- Bechard, Deni "Viral Conservation" The Solutions Journal, February 2014

Journal articles

- Fischer, Anne; Prüfer, Kay; Good, Jeffrey M.; Halbwax, Michel; Wiebe, Victor; André, Claudine; Atencia, Rebeca; Mugisha, Lawrence; Ptak, Susan E.; et al. (29 June 2011). Joly, Etienne, ed. "Bonobos fall within the genomic variation of chimpanzees". PLoS ONE. 6 (6): e21605. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...621605F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021605.

- Zsurka, Gábor; Kudina, Tatiana; Peeva, Viktoriya; Hallmann, Kerstin; Elger, Christian E.; Elger, Konstantin; Khrapko, Konstantin; Kunz, Wolfram S. (2010). "Distinct patterns of mitochondrial genome diversity in bonobos (Pan paniscus) and humans". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 10: 270. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-10-270.

- Wildman, Derek E.; Uddin, Monica; Liu, Guozhen; Grossman, Lawrence I.; Goodman, Morris (10 June 2003). "Implications of natural selection in shaping 99.4% nonsynonymous DNA identity between humans and chimpanzees: Enlarging genus Homo". PNAS. 100 (12): 7181–7188. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.7181W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1232172100. PMC 165850

. PMID 12766228.

. PMID 12766228.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pan paniscus. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Bonobo |

- ARKive – BBC images and movies of the bonobo (Pan paniscus)

- Evolution: Why Sex?

- Bonobos: Wildlife summary from the African Wildlife Foundation

- Primate Info Net Pan paniscus Factsheet

- U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Species Profile

- "The Last Great Ape", an episode of Nova.

- Susan Savage-Rumbaugh: Apes that write, start fires and play Pac-Man – Ted.com

- WWF (World Wide Fund for Nature / World Wildlife Fund) – Bonobo species profile

- Encyclopedia of Life

- San Diego Zoo Library: Bonobo, Pan paniscus

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).

- View the panPan1 genome assembly in the UCSC Genome Browser.