Catapult

A catapult is a ballistic device used to launch a projectile a great distance without the aid of explosive devices—particularly various types of ancient and medieval siege engines.[1] Although the catapult has been used since ancient times, it has proven to be one of the most effective mechanisms during warfare. In modern times the term can apply to devices ranging from a simple hand-held implement (also called a “slingshot”) to a mechanism for launching aircraft from a ship.

Etymology

The word 'catapult' comes from the Latin 'catapulta', which in turn comes from the Greek Ancient Greek: καταπέλτης[2] (katapeltēs), itself from (kata), "downwards"[3] + πάλλω (pallō), "to toss, to hurl".[4][5] Catapults were invented by the ancient Greeks.[6][7]

Greek and Roman catapults

_(14763485952)_(enhanced).jpg)

.jpg)

The catapult and crossbow in Greece are closely intertwined. Primitive catapults were essentially “the product of relatively straightforward attempts to increase the range and penetrating power of missiles by strengthening the bow which propelled them”.[8] The historian Diodorus Siculus (fl. 1st century BC), described the invention of a mechanical arrow-firing catapult (katapeltikon) by a Greek task force in 399 BC.[9][10] The weapon was soon after employed against Motya (397 BC), a key Carthaginian stronghold in Sicily.[11][12] Diodorus is assumed to have drawn his description from the highly rated[13] history of Philistus, a contemporary of the events then. The introduction of crossbows however, can be dated further back: according to the inventor Hero of Alexandria (fl. 1st century AD), who referred to the now lost works of the 3rd-century BC engineer Ctesibius, this weapon was inspired by an earlier foot-held crossbow, called the gastraphetes, which could store more energy than the Greek bows. A detailed description of the gastraphetes, or the “belly-bow”,[14] along with a watercolor drawing, is found in Heron's technical treatise Belopoeica.[15][16]

A third Greek author, Biton (fl. 2nd century BC), whose reliability has been positively reevaluated by recent scholarship,[10][17] described two advanced forms of the gastraphetes, which he credits to Zopyros, an engineer from southern Italy. Zopyrus has been plausibly equated with a Pythagorean of that name who seems to have flourished in the late 5th century BC.[18][lower-alpha 1] He probably designed his bow-machines on the occasion of the sieges of Cumae and Milet between 421 BC and 401 BC.[21][22] The bows of these machines already featured a winched pull back system and could apparently throw two missiles at once.[12]

Philo of Byzantium provides probably the most detailed account on the establishment of a theory of belopoietics (“belos” = projectile; “poietike” = (art) of making) circa 200 BC. The central principle to this theory was that “all parts of a catapult, including the weight or length of the projectile, were proportional to the size of the torsion springs”. This kind of innovation is indicative of the increasing rate at which geometry and physics were being assimilated into military enterprises.[14]

From the mid-4th century BC onwards, evidence of the Greek use of arrow-shooting machines becomes more dense and varied: arrow firing machines (katapaltai) are briefly mentioned by Aeneas Tacticus in his treatise on siegecraft written around 350 BC.[12] An extant inscription from the Athenian arsenal, dated between 338 and 326 BC, lists a number of stored catapults with shooting bolts of varying size and springs of sinews.[23] The later entry is particularly noteworthy as it constitutes the first clear evidence for the switch to torsion catapults which are more powerful than the flexible crossbows and came to dominate Greek and Roman artillery design thereafter.[24] This move to torsion springs was likely spurred by the engineers of Philip II of Macedonia.[14] Another Athenian inventory from 330 to 329 BC includes catapult bolts with heads and flights.[23] As the use of catapults became more commonplace, so did the training required to operate them. Many Greek children were instructed in catapult usage, as evidenced by “a 3rd Century B.C. inscription from the island of Ceos in the Cyclades [regulating] catapult shooting competitions for the young”.[14] Arrow firing machines in action are reported from Philip II's siege of Perinth (Thrace) in 340 BC.[25] At the same time, Greek fortifications began to feature high towers with shuttered windows in the top, which could have been used to house anti-personnel arrow shooters, as in Aigosthena.[26] Projectiles included both arrows and (later) stones that were sometimes lit on fire. Onomarchus of Phocis first used catapults on the battlefield against Philip II of Macedon.[27] Philip's son, Alexander the Great, was the next commander in recorded history to make such use of catapults on the battlefield[28] as well as to use them during sieges.[29]

The Romans started to use catapults as arms for their wars against Syracuse, Macedon, Sparta and Aetolia (3rd and 2nd centuries BC). The Roman machine known as an arcuballista was similar to a large crossbow.[30][31][32] Later the Romans used ballista catapults on their warships.

Other ancient catapults

Ajatshatru is recorded in Jaina texts as having used a catapult in his campaign against the Licchavis.[33]

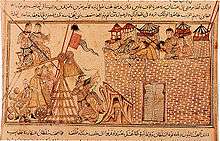

Medieval catapults

Castles and fortified walled cities were common during this period – and catapults were used as a key siege weapon against them. As well as attempting to breach the walls, incendiary missiles could be thrown inside—or early biological warfare attempted with diseased carcasses or putrid garbage catapulted over the walls.

Defensive techniques in the Middle Ages progressed to a point that rendered catapults ineffective for the most part. The Viking siege of Paris (885–6 A.D.) “saw the employment by both sides of virtually every instrument of siege craft known to the classical world, including a variety of catapults,” to little effect, resulting in failure.[8]

The most widely used catapults throughout the Middle Ages were as follows:[34]

- Ballista

- Ballistae were similar to giant crossbows and were designed to work through torsion. The ammunition used were basically giant arrows or darts made from wood with an iron tip. These arrows were then shot “along a flat trajectory” at a target. Ballistae are notable for their high degree of accuracy, but also their lack of firepower compared to that of a Mangonel or Trebuchet. Because of their immobility, most Ballistae were constructed on site following a siege assessment by the commanding military officer.[34]

- Springald

- The springald's design is similar to that of the ballista's, in that it was effectively a crossbow propelled by tension. The Springald's frame was more compact, allowing for use inside tighter confines, such as the inside of a castle or tower. This compromised the force though, making it an anti-personnel weapon at best.[34]

- Mangonel

- These machines were designed to throw heavy projectiles from a “bowl-shaped bucket at the end of its arm”. Mangonels were mostly used for “firing various missiles at fortresses, castles, and cities,” with a range of up to 1300 feet. These missiles included anything from stones to excrement to rotting carcasses. Mangonels were relatively simple to construct, and eventually wheels were added to increase mobility.[34]

- Onager

- Mangonels are also sometimes referred to as Onagers. Onager catapults initially launched projectiles from a sling, which was later changed to a “bowl-shaped bucket”. The word 'Onager' is derived from the Greek word 'onagros' for wild ass, referring to the “kicking motion and force”[34] that were recreated in the Mangonel's design. Historical records regarding onagers are scarce. The most detailed account of Mangonel use is from “Eric Marsden's translation of a text written by Ammianus Marcellius in the 4th Century AD” describing its construction and combat usage.[35]

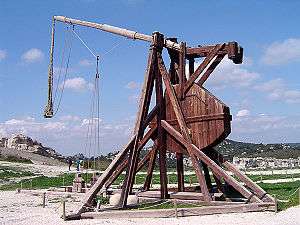

- Trebuchet

- Trebuchets were probably the most powerful catapult employed in the Middle Ages. The most commonly used ammunition were stones, but “darts and sharp wooden poles” could be substituted if necessary. The most effective kind of ammunition though involved fire, such as “firebrands, and deadly Greek Fire”. Trebuchets came in two different designs: Traction, which were powered by people, or Counterpoise, where the people were replaced with “a weight on the short end”.[34] The most famous historical account of trebuchet use dates back to the siege of Stirling Castle in 1304, when the army of Edward I constructed a giant trebuchet known as Warwolf, which then proceeded to “level a section of [castle] wall, successfully concluding the siege.”[35]

- Couillard

- A simplified trebuchet, where the trebuchet's single counterweight is split, swinging on either side of a central support post.

- Leonardo da Vinci's catapult

- Leonardo da Vinci sought to improve the efficiency and range of earlier designs. His design incorporated a large wooden leaf spring as an accumulator to power the catapult. Both ends of the bow are connected by a rope, similar to the design of a bow and arrow. The leaf spring was not used to pull the catapult armature directly, rather the rope was wound around a drum. The catapult armature was attached to this drum which would be turned until enough potential energy was stored in the deformation of the spring. The drum would then be disengaged from the winding mechanism, and the catapult arm would snap around. Though no records exist of this design being built during Leonardo's lifetime, contemporary enthusiasts have reconstructed it.

Modern use

The last large scale military use of catapults was during the trench warfare of World War I. During the early stages of the war, catapults were used to throw hand grenades across no man's land into enemy trenches. They were eventually replaced by small mortars.

In the 1840s the invention of vulcanized rubber allowed the making of small hand-held catapults, either improvised from Y-shaped sticks or manufactured for sale; both were popular with children and teenagers. These devices were also known as slingshots in the USA.

Special variants called aircraft catapults are used to launch planes from land bases and sea carriers when the takeoff runway is too short for a powered takeoff or simply impractical to extend. Ships also use them to launch torpedoes and deploy bombs against submarines. Small catapults, referred to as "traps", are still widely used to launch clay targets into the air in the sport of clay pigeon shooting.

Until recently, catapults were used by thrill-seekers to experience being catapulted through the air. The practice has been discontinued due to fatalities, when the participants failed to land onto the safety net.[36][37]

Pumpkin chunking is another widely popularized use, in which people compete to see who can launch a pumpkin the farthest by mechanical means (although the world record is held by a pneumatic air cannon).

In January 2011, PopSci.com, the news blog version of Popular Science magazine, reported that a group of smugglers used a homemade catapult to deliver cannabis into the United States from Mexico. The machine was found 20 feet from the border fence with 4.4 pounds (2.0 kg) bales of cannabis ready to launch.[38]

Models

In the US, catapults of all types and sizes are being built for school science and history fairs, competitions or as a hobby. Catapult projects can inspire students to study different subjects including physics, engineering, science, math and history. These kits can be purchased from Renaissance Fairs, or from several online stores.

See also

- Siege engine

- Onager (siege weapon)

- Trebuchet

- Ballista

- Mangonel

- Petraria Arcatinus

- Sling (weapon)

- Slingshot

- Aircraft catapult

- Mass driver

Notes

References

- ↑ Gurstelle, William (2004). The art of the catapult: build Greek ballista, Roman onagers, English trebuchets, and more ancient artillery. Chicago: Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-55652-526-1. OCLC 54529037.

- ↑

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Catapult". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Catapult". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. - ↑ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert, "κατά", A Greek-English Lexicon (definition), Perseus, Tufts

- ↑ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert, "πάλλω", A Greek-English Lexicon, Perseus, Tufts.

- ↑ "catapult", Dictionaries (definition), Oxford

- ↑ Schellenberg, Hans Michael (2006). "Diodor von Sizilien 14,42,1 und die Erfindung der Artillerie im Mittelmeerraum" (PDF). Frankfurter Elektronische Rundschau zur Altertumskunde. 3: 14–23.

- ↑ Marsden 1969, pp. 48–64.

- 1 2 Hacker, Barton C, Greek Catapults and Catapult Technology: Science, Technology, and War in Ancient World, JSTOR 3102042.

- ↑ Diod. Sic. 14.42.1.

- 1 2 Campbell 2003, p. 3.

- ↑ Diod. Sic. 14.50.4

- 1 2 3 Campbell 2003, p. 8.

- ↑ Marsden 1969, pp. 48f.

- 1 2 3 4 Cuomo, Serafina, The Sinews of War: Ancient Catapults, JSTOR 3836219.

- ↑ Campbell 2003, p. 4.

- ↑ Burstein, Stanley M; Donlan, Walter; Pomeroy, Sarah B; Roberts, Jennifer Tolbert (1999), Ancient Greece: A Political, Social, and Cultural History, Oxford University Press, p. 366, ISBN 0-19-509742-4.

- ↑ Lewis 1999.

- ↑ Kingsley, Peter (1995), Ancient Philosophy, Mystery and Magic, Oxford: Clarendon, pp. 150ff.

- ↑ Lewis 1999, p. 160.

- ↑ de Camp, L Sprague (1961), "Master Gunner Apollonios", Technology and Culture, 2 (3): 240–4 (241), doi:10.2307/3101024.

- ↑ Biton 65.1–67.4, 61.12–65.1.

- ↑ Campbell 2003, p. 5.

- 1 2 Marsden 1969, p. 57.

- ↑ Campbell 2003, pp. 8ff.

- ↑ Marsden 1969, p. 60.

- ↑ Ober, Josiah (1987), "Early Artillery Towers: Messenia, Boiotia, Attica, Megarid", American Journal of Archaeology, 91 (4): 569–604 (569), doi:10.2307/505291.

- ↑ Ashley 1998, pp. 50, 446.

- ↑ Ashley 1998, p. 50.

- ↑ Skelton, Debra; Dell, Pamela (2003), Empire of Alexander the Great, New York: Facts on File, pp. 21, 26, 29, ISBN 978-0-8160-5564-7, retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ↑ "Arcuballista", Dictionnaire des antiquités grecques et romaines [Dictionary of Greek and Roman antiquities] (in French), FR: Univ TLSE II.

- ↑ Bachrach, Bernard S (2001), Early Carolingian Warfare: Prelude to Empire, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 110–12, ISBN 978-0-8122-3533-3, retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ↑ Payne-Gallwey, Ralph (2007), The Crossbow: Its Military and Sporting History, Construction and Use, New York: Skyhorse, pp. 43–44, ISBN 978-1-60239-010-2, retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ↑ Singh, U. (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education. p. 272. ISBN 9788131711200. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Catapults", Middle ages, UK.

- 1 2 Catapults info.

- ↑ "Inquest told of student catapult death". October 31, 2005. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- ↑ "BBC NEWS UK England Oxfordshire - Safety doubts over catapult death". November 2, 2005. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- ↑ "Mexican authorities seize homemade marijuana hurling catapult at border", Pop Sci, Jan 2011.

Bibliography

- Ashley, James R (1998), The Macedonian Empire: The Era of Warfare Under Philip II and Alexander the Great, 359–323 BC, Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co, ISBN 978-0-7864-1918-0, retrieved January 31, 2013.

- Campbell, Duncan (2003), Greek and Roman Artillery 399 BC – AD 363, Oxford: Osprey, ISBN 1-84176-634-8.

- Lewis, MJT (1999), "When was Biton?", Mnemosyne, 52 (2): 159–68, doi:10.1163/1568525991528860.

- Marsden, Eric William (1969), Greek and Roman Artillery: Historical Development, Oxford: Clarendon, ISBN 978-0-19-814268-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Catapult. |

| Look up catapult in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

"Catapult". Encyclopædia Britannica. 5 (11th ed.). 1911.

"Catapult". Encyclopædia Britannica. 5 (11th ed.). 1911.- "Types", Ancient Greek Artillery Technology, DE: Mlahanas.

- "Catapult Plans and Design", Trebuchet store, Red stone projects.

- "Animated Catapults", Trebuchet store, Red stone projects.

- "Medieval Catapult Articles", Medieval castle siege weapons.

- A Modern Spring Loaded Catapult in Action, FVC3.