Cave hyena

| Cave hyena Temporal range: Middle Pleistocene–Late Pleistocene | |

|---|---|

| |

| Crocuta crocuta spelaea skeleton from the Muséum de Toulouse. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Hyaenidae |

| Genus: | Crocuta |

| Species: | C. crocuta |

| Subspecies: | †C. c. spelaea |

The cave hyena (Crocuta crocuta spelaea), also known as the Ice Age spotted hyena,[1] was a paleosubspecies of spotted hyena[2] which ranged from the Iberian Peninsula to eastern Siberia.[3] It is one of the best known mammals of the Ice Age, and is well represented in many European bone caves.[4] The cave hyena was a highly specialised animal, with its progressive and regressive features being more developed than in its modern African relative.[5] It preyed on large mammals (primarily wild horses, steppe wisent and woolly rhinoceros), and was responsible for the accumulation of hundreds of large Pleistocene mammal bones in areas including horizontal caves, sinkholes, mud pits and muddy areas along rivers.[1]

The cause of the cave hyena's extinction is not fully understood, though it could have been due to a combination of factors, including climate change and competition with other predators.[6][7]

Description and paleoecology

The European cave hyena was much larger than its modern African cousin, having been estimated to weigh 102 kg (225 lb).[8] In Late Pleistocene specimens from Europe, the cave hyena's metacarpals and metatarsals are shorter and thicker, while the humerus and femur are longer,[4] thus indicating adaptations to a different habitat from that of the modern spotted hyena.[9] As with the African subspecies, female cave hyenas were larger than their male counterparts.[1] Paleolithic rock art depicting the cave hyena shows that it retained the spotted pelt of its African relative.[10]

Several den sites found in Europe indicate that the cave hyena preferentially targeted large prey, with wild horses predominating, followed by steppe bison and woolly rhinoceros.[1][11][12] The cave hyena's favouring of horses is consistent with the behaviour of the modern African spotted hyena, which mostly hunts zebras. Secondary prey species included reindeer, red deer, giant deer, European ass, chamois and ibex.[1] A small number of wolf remains have also been discovered in hyena den sites. The cave hyena likely killed wolves due to intraguild competition, though their presence in the cave site indicates that they were also fed upon, which is unusual among carnivores.[12] Similarly, cave lion and bear remains have been discovered in hyena den sites, thus indicating that hyenas may have scavenged on or killed them.[1]

History of discovery and classification

_Cave_Hyenas_%26_Woolly_Rhino.png)

Although the first full account of the cave hyena was given by Georges Cuvier in 1812, skeletal fragments of the cave hyena have been described in scientific literature since the 18th century, though they were frequently misidentified. The first recorded mention of the cave hyena in literature occurs in Kundmann's 1737 tome Rariora Naturæ et Artis, where the author misidentified a hyena's mandibular ramus as that of a calf. In 1774, Esper erroneously described hyena teeth discovered in Gailenreuth as those of a lion, and in 1784, Collini described a cave hyena skull as that of a seal. The past presence of hyenas in Great Britain was revealed after William Buckland's examination of the contents of Kirkdale Cave, which was discovered to have once been the location of several hyena den sites. Buckland's findings were followed by further discoveries by Clift and Whidbey in Oreston, Plymouth.[13]

In his own 1812 account, Cuvier mentioned a number of European localities where cave hyena remains were found, and considered it a different species from the spotted hyena on account of its superior size. He elaborated his view in his Ossemens Fossiles (1823), noting how the cave hyena's digital extremities were shorter and thicker than those of the spotted hyena. His views were largely accepted throughout the first half of the 19th century, finding support in de Blainville and Richard Owen among others. Further justifications in separating the two animals included differences in the tubercular portion of the lower carnassial. Boyd Dawkins, writing in 1865, was the first to definitely cast doubt over the separation of the spotted and cave hyena, stating that the aforementioned tooth characteristics were consistent with mere individual variation. Writing again in 1877, he further stated after comparing the two animals' skulls that there are no characters of specific value.[13]

Analyses of the DNA sequences of the mitochondrial cytochrome b genes in both modern African and Pleistocene spotted hyenas demonstrated that the two were the same species.[2]

Relationships with hominids

Interactions

Kills partially processed by Neanderthals and then by cave hyenas indicate that hyenas would occasionally steal Neanderthal kills; and cave hyenas and Neanderthals competed for cave sites. Many caves show alternating occupations by hyenas and Neanderthals.[14] The presence of large hyena populations in the Russian Far East may have delayed the human colonisation of North America.[3] There is fossil evidence of humans in Middle Pleistocene Europe butchering and presumably consuming hyenas.[15]

In rock art

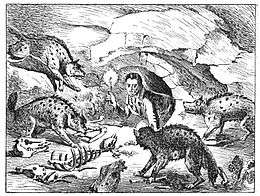

The cave hyena is depicted in a few examples of Upper Palaeolithic rock art in France. A painting from the Chauvet Cave depicts a hyena outlined and represented in profile, with two legs, with its head and front part with well distinguishable spotted coloration pattern. Because of the specimen's steeped profile, it is thought that the painting was originally meant to represent a cave bear, but was modified as a hyena. In Lascaux, a red and black rock painting of a hyena is present in the part of the cave known as the Diverticule axial, and is depicted in profile, with four limbs, showing an animal with a steep back. The body and the long neck have spots, including the flanks. An image on a cave in Ariège shows an incompletely outlined and deeply engraved figure, representing a part of an elongated neck, smoothly passing into part of the animal’s forelimb on the proximal side. Its head is in profile, with a possibly re-engraved muzzle. The ear is typical of the spotted hyena, as it is rounded. An image in the Le Gabillou Cave in Dordogne shows a deeply engraved zoomorphic figure with a head in frontal view and an elongated neck with part of the forelimb in profile. It has large round eyes and short, rounded ears which are set far from each other. It has a broad, line-like mouth that evokes a smile. Though originally thought to represent a composite or zoomorphic hybrid, it is probable it is a spotted hyena based on its broad muzzle and long neck. The relative scarcity of hyena depictions in Paleolithic rock art has been theorised to be due to the animal's lower rank in the animal worship hierarchy; the cave hyena's appearance was likely unappealing to Ice Age hunters, and it was not sought after as prey. Also, it was not a serious rival like the cave lion or bear, and it lacked the impressiveness of the mammoth or woolly rhino.[10]

Extinction

The ultimate cause of the cave hyena's extinction is still poorly understood. While climate change has been forwarded as a possible reason, it is insufficient to explain the animal's complete extinction; although the extremely cold conditions following the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) diminished favourable hyena habitat in Northern Europe, and separated cave hyena populations from their African kin, there were still habitable localities in Southern and Central Europe at that time, and the animal survived many other cold periods during the Pleistocene.[7] In the Iberian Peninsula, climate change was ruled out as the sole cause of the cave hyena's extinction, for although the LGM resulted in a mass extinction of several hyena prey species, the red deer and several other herbivore species survived and would have still have adequately sustained hyena populations.[16] In Western Europe at least, the cave hyena's extinction coincided with a decline in grasslands 12,500 years ago. Europe experienced a massive loss of lowland habitats favoured by cave hyenas, and a corresponding increase in mixed woodlands. Cave hyenas, under these circumstances, would have been outcompeted by wolves and humans which were as much at home in forests as in open lands, and in highlands as in lowlands. Cave hyena populations began to shrink after roughly 20,000 years ago, completely disappearing from Western Europe between 14-11,000 years ago, and earlier in some areas.[6]

Gallery

_Cave_Hyena_Skull_1.png) Cranium from Wookey Hole, now in Taunton Museum

Cranium from Wookey Hole, now in Taunton Museum_Cave_Hyena_Skull_2.png) Skull from Wookey Hole, now in Taunton Museum

Skull from Wookey Hole, now in Taunton Museum_Cave_Hyena_Manus_1.png) Anterior and posterior views of the right forefoot, from Tor Bryan Caves near Torquay, now kept in British Museum

Anterior and posterior views of the right forefoot, from Tor Bryan Caves near Torquay, now kept in British Museum_Cave_Hyena_Pes_1.png) Anterior and posterior views of the right hind foot, from Tor Bryan Caves near Torquay, now kept in British Museum.

Anterior and posterior views of the right hind foot, from Tor Bryan Caves near Torquay, now kept in British Museum._Cave_Hyena_Dentition_1.png) Permanent dentition of a Pleistocene cave hyena from Tor Bryan Caves near Torquay, now kept in British Museum.

Permanent dentition of a Pleistocene cave hyena from Tor Bryan Caves near Torquay, now kept in British Museum._Cave_Hyena_Dentition_2.png) Permanent dentition, from Tor Bryan Caves near Torquay (now kept in British Museum), Creswell Caves in Derbyshire (now kept in Manchester's Owen College Museum), Kirkdale Cave and Wookey Hole (now kept in Oxford Museum).

Permanent dentition, from Tor Bryan Caves near Torquay (now kept in British Museum), Creswell Caves in Derbyshire (now kept in Manchester's Owen College Museum), Kirkdale Cave and Wookey Hole (now kept in Oxford Museum)._Cave_Hyena_Jaws_%26_Cranium.png) Jaws and cranium from Kent's Hole, Torquay (now in British Museum) and Wookey Hole (now in Taunton Museum).

Jaws and cranium from Kent's Hole, Torquay (now in British Museum) and Wookey Hole (now in Taunton Museum)._Cave_Hyena_Vertebrae.png) Vertebrae from Wookey Hole (now in Taunton Museum).

Vertebrae from Wookey Hole (now in Taunton Museum)._Cave_Hyena_Vertebrae_2.png) Vertebrae from Wookey Hole (now in Taunton Museum).

Vertebrae from Wookey Hole (now in Taunton Museum)._Cave_Hyena_Vertebrae_3.png) Vertebrae from Wookey Hole (now in Taunton Museum).

Vertebrae from Wookey Hole (now in Taunton Museum)._Cave_Hyena_Pelvis.png) Pelvis from Wookey Hole (now in Taunton Museum).

Pelvis from Wookey Hole (now in Taunton Museum)._Cave_Hyena_Scapula.png) Scapula from Creswell Caves, Derbyshire (now in Owens College Museum, Manchester).

Scapula from Creswell Caves, Derbyshire (now in Owens College Museum, Manchester).

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 DIEDRICH, C.G. & ŽÁK, K. 2006. Prey deposits and den sites of the Upper Pleistocene hyena Crocuta crocuta spelaea (Goldfuss, 1823) in horizontal and vertical caves of the Bohemian Karst (Czech Republic). Bulletin of Geosciences 81(4), 237–276 (25 figures). Czech Geological Survey, Prague. ISSN 1214-1119.

- 1 2 Rohland, N, Pollack, JL, Nagel, D, Beauval, C, Airvaux J, Paabo, S & Hofreiter, M, 2005. The population history of extant and extinct hyenas. Molecular Biology and Evolution,. 22: 2435-2443.

- 1 2 Summerill, Lynette; Gnawed Bones tell Tales, Summer 2003, ASU Research

- 1 2 Kurtén, Björn (1968). Pleistocene mammals of Europe. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. pp. 69-72.

- ↑ Martin, Paul S. (1989). Quaternary Extinctions: A Prehistoric Revolution. University of Arizona Press. p. 496. ISBN 0816511004

- 1 2 C. Stiner, Mary (2004) Comparative ecology and taphonomy of spotted hyenas, humans, and wolves in Pleistocene Italy, Revue de Paléobiologie, Genève. (December 2004) 23 (2) : 771-785. ISSN 0253-6730

- 1 2 Varela, S., Lobo, J. M., Rodríguez, J. and Batra, P. (2010). Were the Late Pleistocene climatic changes responsible for the disappearance of the European spotted hyena populations? Quaternary Science Reviews, 29: 2027-2035.

- ↑ Meloro, C., 2007. Plio-Pleistocene large carnivores from the Italian peninsula: functional morphology and macroecology. Ph.D. Thesis, Univ. Naples Federico II.

- ↑ Dockner, M., 2006. Comparison of Crocuta crocuta crocuta and Crocuta crocuta spelaea through computer tomography. Ph.D. Thesis, Univ. Vienna, Austria.

- 1 2 Spassov N.; Stoytchev T. 2004. The presence of cave hyaena (Crocuta crocuta spelaea) in the Upper Palaeolithic rock art of Europe. Historia naturalis bulgarica, 16: 159-166.

- ↑ Diedrich, C. 2010. “Specialized horse killers in Europe – foetal horse remains in the Late Pleistocene Srbsko Chlum-Komín Cave hyena den in the Bohemian Karst (Czech Republic) and actualistic comparisons to modern African spotted hyenas as zebra hunters.” Quaternary International, vol. 220, no. 1-2, pp. 174-187.

- 1 2 Dusseldorp, Gerrit Leendert. (2008). A View to a Kill: Investigating Middle Palaeolithic Subsistence Using an Optimal Foraging Perspective. Sidestone Press. pp. 127-143. ISBN 9088900205

- 1 2 Dawkins, William Boyd; Sanford, W. Ayshford; Reynolds, Sydney Hugh. (1866). A monograph of the British pleistocene mammalia. Palaeontographical Society (Great Britain). pp. 1-6.

- ↑ Fosse, P. 1999. "Cave occupation during Palaeolithic times: Man and/or Hyena?" in The Role of Early Humans in the accumulation if European Lower and Middle Palaeolithic bone assemblages, Ergebnisse eines Kolloquiums, vol. 42, Monographien. Edited by S. Gaudzinski and E. Turner, pp. 73-88. Bonn: Verlag des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums.

- ↑ Rodríguez-Hidalgo, A. (2010). "The scavenger or the scavenged?" (PDF). Journal of Taphonomy. 1: 75–76.

- ↑ Varela, S., Lobo, J. M. and Rodríguez, J. (2010). Are herbivores and spotted hyena extinctions at the end of the Pleistocene related? Zona Arqueologica, 13: 76-91.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Crocuta crocuta spelaea. |

- (French) Cuvier, Georges, Note sur les ossemens fossiles d’hyènes, Nouveau Bulletin des Sciences, Tome 1, 1807-1809 (pp. 149–150).