Charles Eaton (RAAF officer)

| Charles Eaton | |

|---|---|

|

Group Captain Eaton commanding RAAF Southern Area, 1945 | |

| Nickname(s) | "Moth" |

| Born |

21 December 1895 Lambeth, London, England |

| Died |

12 November 1979 (aged 83) Frankston, Victoria, Australia |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch | |

| Years of service |

|

| Rank | Group Captain |

| Unit |

|

| Commands held |

|

| Battles/wars |

|

| Awards | |

| Other work | Diplomat |

Charles Eaton, OBE, AFC (21 December 1895 – 12 November 1979) was a senior officer and aviator in the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), who later served as a diplomat. Born in London, he joined the British Army upon the outbreak of World War I and saw action on the Western Front before transferring to the Royal Flying Corps in 1917. Posted as a bomber pilot to No. 206 Squadron, he was twice captured by German forces, and twice escaped. Eaton left the military in 1920 and worked in India until moving to Australia in 1923. Two years later he joined the RAAF, serving initially as an instructor at No. 1 Flying Training School. Between 1929 and 1931, he was chosen to lead three expeditions to search for lost aircraft in Central Australia, gaining national attention and earning the Air Force Cross for his "zeal and devotion to duty".

In 1939, on the eve of World War II, Eaton became the inaugural commanding officer of No. 12 (General Purpose) Squadron at the newly established RAAF Station Darwin in Northern Australia. Promoted group captain the following year, he was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire in 1942. He took command of No. 79 Wing at Batchelor, Northern Territory, in 1943, and was mentioned in despatches during operations in the South West Pacific. Retiring from the RAAF in December 1945, Eaton took up diplomatic posts in the Dutch East Indies, heading a United Nations commission as Consul-General during the Indonesian National Revolution. He returned to Australia in 1950, and served in Canberra for a further two years. Popularly known as "Moth" Eaton, he was a farmer in later life, and died in 1979 at the age of 83. He is commemorated by several memorials in the Northern Territory.

Early life and World War I

Charles Eaton was born on 21 December 1895 in Lambeth, London, the son of William Walpole Eaton, a butcher, and his wife Grace. Schooled in Wandsworth, Charles worked in Battersea Town Council from the age of fourteen, before joining the London Regiment upon the outbreak of World War I in August 1914.[1][2] Attached to a bicycle company in the 24th Battalion of the 47th Division, he arrived at the Western Front in March 1915. He took part in trench bombing missions and attacks on enemy lines of communication, seeing action in the Battles of Aubers Ridge, Festubert, Loos, and the Somme.[2][3]

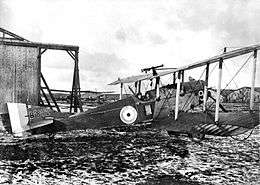

On 14 May 1915, Eaton transferred to the Royal Flying Corps (RFC), undergoing initial pilot training at Oxford. While he was landing his Maurice Farman Shorthorn at the end of his first solo flight, another student collided with him and was killed, but Eaton emerged uninjured.[2] He was commissioned in August and was awarded his wings in October. Ranked lieutenant, he served with No. 110 Squadron, which operated Martinsyde G.100 "Elephant" fighters out of Sedgeford, defending London against Zeppelin airships.[1][4] Transferred to the newly formed Royal Air Force (RAF) in April 1918, he was posted the following month to France flying Airco DH.9 single-engined bombers with No. 206 Squadron.[2] On 29 June, he was shot down behind enemy lines and captured in the vicinity of Nieppe. Incarcerated in Holzminden prisoner-of-war camp, Germany, Eaton escaped but was recaptured and court-martialled, after which he was kept in solitary confinement. He later effected another escape and succeeded in rejoining his squadron in the final days of the war.[1][5]

Between the wars

Eaton remained in the RAF following the cessation of hostilities. He married Beatrice Godfrey in St. Thomas's church at Shepherd's Bush, London, on 11 January 1919. Posted to No. 1 Squadron, he was a pilot on the first regular passenger service between London and Paris, ferrying delegates to and from the Peace Conference at Versailles.[1][5] Eaton was sent to India in December to undertake aerial survey work, including the first such survey of the Himalayas.[1][6] He resigned from the RAF in July 1920, remaining in India to take up employment with the Imperial Forest Service. After successfully applying for a position with the Queensland Forestry Service, he and his family migrated to Australia in 1923.[6][7] Moving to South Yarra, Victoria, he enlisted as a flying officer in the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) at Laverton on 14 August 1925.[8] He was posted to No. 1 Flying Training School at RAAF Point Cook, as a flight instructor, where he became known as a strict disciplinarian who "trained his pilots well".[5][6] Here Eaton acquired his nickname of "Moth", the Air Force's basic trainer at this time being the De Havilland DH.60 Moth. Promoted flight lieutenant in February 1928,[1] he flew a Moth in the 1929 East-West Air Race from Sydney to Perth, as part of the celebrations for the Western Australia Centenary; he was the sixth competitor across the line, after fellow RFC veteran Jerry Pentland.[9][10]

Regarded as one of the RAAF's most skilful cross-country pilots and navigators, Eaton came to public attention as leader of three military expeditions to find lost aircraft in Central Australia between 1929 and 1931.[11][12] In April 1929, he coordinated the Air Force's part in the search for aviators Keith Anderson and Bob Hitchcock, missing in their aircraft the Kookaburra while themselves looking for Charles Kingsford Smith and Charles Ulm, who had force landed the Southern Cross in north Western Australia during a flight from Sydney. Three of the RAAF's five "ancient" DH.9 biplanes went down in the search—though all crews escaped injury—including Eaton's, which experienced what he labelled "a good crash" on 21 April near Tennant Creek after the engine's pistons melted.[12][13] The same day, Captain Lester Brain, flying a Qantas aircraft, located the wreck of the Kookaburra in the Tanami Desert, approximately 130 kilometres (81 mi) east-south-east of Wave Hill. Setting out from Wave Hill on 23 April, Eaton led a ground party across rough terrain that reached the crash site four days later and buried the crew, who had perished of thirst and exposure. Not a particularly religious man, he recalled that after the burial he saw a perfect cross formed by cirrus cloud in an otherwise clear blue sky above the Kookaburra.[11][13] The Air Board described the RAAF's search as taking 240 hours flying time "under the most trying conditions ... where a forced landing meant certain crash".[11] In November 1930, Eaton was selected to lead another expedition for a missing aircraft near Ayers Rock, but it was called off soon afterwards when the pilot showed up in Alice Springs. The next month, he was ordered to search for W.L. Pittendrigh and S.J. Hamre, who had disappeared in the biplane Golden Quest 2 while attempting to discover Lasseter's Reef. Employing a total of four DH.60 Moths, the RAAF team located the missing men near Dashwood Creek on 7 January 1931, and they were rescued four days later by a ground party accompanied by Eaton. Staying in nearby Alice Springs, he recommended a site for the town's new airfield, which was approved and has remained in use since its construction.[12][14]

Eaton was awarded the Air Force Cross on 10 March 1931 "in recognition of his zeal and devotion to duty in conducting flights to Central Australia in search of missing aviators".[15] The media called him the "'Knight Errant' of the desert skies".[12] Aside from his crash landing in the desert while searching for the Kookaburra, Eaton had another narrow escape in 1929 when he was test flying the Wackett Warrigal I with Sergeant Eric Douglas. Having purposely put the biplane trainer into a spin and finding no response in the controls when he tried to recover, Eaton called on Douglas to bail out. When Douglas stood up to do so, the spin stopped, apparently due to his torso changing the airflow over the tail plane. Eaton then managed to land the aeroplane, he and his passenger both badly shaken by the experience.[16] In December 1931, he was posted to No. 1 Aircraft Depot at Laverton, where he continued to fly as well as performing administrative work. Promoted squadron leader in 1936,[1] he undertook a clandestine mission around the new year to scout for suitable landing grounds in the Dutch East Indies, primarily Timor and Ambon. Wearing civilian clothes, he and his companion were arrested and held for three days by local authorities in Koepang, Dutch Timor.[17] Eaton was appointed commanding officer (CO) of No. 21 Squadron in May 1937, one of his first tasks being to undertake another aerial search in Central Australia, this time for prospector Sir Herbert Gepp, who was subsequently discovered alive and well.[1][12] Later that year, Eaton presided over the court of inquiry into the crash of a Hawker Demon biplane in Victoria, recommending a gallantry award for Aircraftman William McAloney, who had leapt into the Demon's burning wreckage in an effort to rescue its pilot; McAloney subsequently received the Albert Medal for his heroism.[18]

Following a 1937 decision to establish the first north Australian RAAF base, in April 1938 Eaton, now on the headquarters staff of RAAF Station Laverton, and Wing Commander George Jones, Director of Personnel Services at RAAF Headquarters, began developing plans for the new station, to be commanded by Jones, and a new squadron that would be based there, led by Eaton. The next month they flew an Avro Anson on an inspection tour of Darwin, Northern Territory, site of the proposed base. Delays meant that No. 12 (General Purpose) Squadron was not formed until 6 February 1939 at Laverton. Jones had by now moved on to another posting but Eaton took up the squadron's command as planned. Promoted to wing commander on 1 March, he and his equipment officer, Flying Officer Hocking, were ordered to build up the unit as quickly as possible, and established an initial complement of fourteen officers and 120 airmen, plus four Ansons and four Demons, within a week. An advance party of thirty NCOs and airmen under Hocking began moving to Darwin on 1 July. Staff were initially accommodated in a former meatworks built during World War I, and life at the newly established air base had a "distinctly raw, pioneering feel about it" according to historian Chris Coulthard-Clark. Morale, though, was high.[19] On 31 August, No. 12 Squadron launched its first patrol over the Darwin area, flown by one of seven Ansons that had so far been delivered. These were augmented by a flight of four CAC Wirraways (replacing the originally planned force of Demons) that took off from Laverton on 2 September, the day before Australia declared war, and arrived in Darwin four days later. A fifth Wirraway in the flight crashed on landing at Darwin, killing both crewmen.[19][20]

World War II

Once war was declared, Darwin began to receive more attention from military planners. In June 1940, No. 12 Squadron was "cannibalised" to form two additional units, Headquarters RAAF Station Darwin and No. 13 Squadron. No. 12 Squadron retained its Wirraway flight, while its two flights of Ansons went to the new squadron; these were replaced later that month by more capable Lockheed Hudsons.[21] Eaton was appointed CO of the base, gaining promotion to temporary group captain in September.[1] His squadrons were employed in escort, maritime reconnaissance, and coastal patrol duties, the overworked aircraft having to be sent to RAAF Station Richmond, New South Wales, after every 240 hours flying time—with a consequent three-week loss from Darwin's strength—as deep maintenance was not yet possible in the Northern Territory.[21] Soon after the establishment of Headquarters RAAF Station Darwin, Minister for Air James Fairbairn visited the base. Piloting his own light plane, he was greeted by four Wirraways that proceeded to escort him into landing; the Minister subsequently complimented Eaton on the "keen-ness and efficiency of all ranks", particularly considering the challenging environment.[22] When Fairbairn died in the Canberra air disaster shortly afterwards, his pilot was Flight Lieutenant Robert Hitchcock, son of Bob Hitchcock of the Kookaburra and also a former member of Eaton's No. 21 Squadron.[23][24]

As senior air commander in the region, Eaton sat on the Darwin Defence Co-ordination Committee. He was occasionally at loggerheads with his naval counterpart, Captain E.P. Thomas, and also incurred the ire of trade unionists when he used RAAF staff to unload ships in Port Darwin during industrial action; Eaton himself took part in the work, shovelling coal alongside his men.[25] On 25 February 1941, he made a flight north to reconnoitre Timor, Ambon, and Babo in Dutch New Guinea for potential use by the RAAF in any Pacific conflict.[23] By April, the total strength based at RAAF Station Darwin had increased to almost 700 officers and airmen; by the following month it had been augmented by satellite airfields at Bathurst Island, Groote Eylandt, Batchelor, and Katherine.[21][26] Handing over command of Darwin to Group Captain Frederick Scherger in October, Eaton took charge of No. 2 Service Flying Training School near Wagga Wagga, New South Wales.[1][27] His "marked success", "untiring energy", and "tact in handling men" while in the Northern Territory were recognised in the new year with his appointment as an Officer of the Order of the British Empire.[28] Eaton became CO of No. 1 Engineering School and its base, RAAF Station Ascot Vale, Victoria, in April 1942.[1][21] Twelve months later in Townsville, Queensland, he formed No. 72 Wing, which subsequently deployed to Merauke in Dutch New Guinea, comprising No. 84 Squadron (flying CAC Boomerang fighters), No. 86 Squadron (P-40 Kittyhawk fighters), and No. 12 Squadron (A-31 Vengeance dive bombers).[29] His relations with North-Eastern Area Command in Townsville were strained; "mountains were made out of molehills" in his opinion, and he was reassigned that July to lead No. 2 Bombing and Gunnery School in Port Pirie, South Australia.[1]

On 30 November 1943, Eaton returned to the Northern Territory to establish No. 79 Wing at Batchelor, comprising No. 1 and No. 2 Squadrons (flying Bristol Beaufort light reconnaissance bombers), No. 31 Squadron (Bristol Beaufighter long-range fighters), and No. 18 (Netherlands East Indies) Squadron (B-25 Mitchell medium bombers). He developed a good relationship with his Dutch personnel, who called him "Oom Charles" (Uncle Charles).[30][31] Operating under the auspices of North-Western Area Command (NWA), Darwin, Eaton's forces participated in the New Guinea and North-Western Area Campaigns during 1944, in which he regularly flew on missions himself.[31][32] Through March–April, his Beaufighters attacked enemy shipping, while the Mitchells and Beauforts bombed Timor on a daily basis as a prelude to Operations Reckless and Persecution, the invasions of Hollandia and Aitape. On 19 April, he organised a large raid against Su, Dutch Timor, employing thirty-five Mitchells, Beauforts and Beaufighters to destroy the town's barracks and fuel dumps, the results earning him the personal congratulations of the Air Officer Commanding NWA, Air Vice Marshal "King" Cole, for his "splendid effort".[31][32] On the day of the Allied landings, 22 April, the Mitchells and Beaufighters made a daylight raid on Dili, Portuguese Timor. The ground assault met little opposition, credited in part to the air bombardment in the days leading up to it.[31] In June–July, No. 79 Wing supported the Allied attack on Noemfoor.[33] Eaton was recommended to be mentioned in despatches on 28 October 1944 for his "Gallant and distinguished service" in NWA; this was promulgated in the London Gazette on 9 March 1945.[34][35]

Completing his tour with No. 79 Wing, Eaton was appointed Air Officer Commanding Southern Area, Melbourne, in January 1945. The German submarine U-862 operated off southern Australia during the first months of 1945, and the few combat units in Eaton's command were heavily engaged in anti-submarine patrols which sought to locate this and any other U-boats in the area. The Air Officer Commanding RAAF Command, Air Vice Marshal Bill Bostock, considered the sporadic attacks to be partly "nuisance value", designed to draw Allied resources away from the front line of the South West Pacific war. In April, Eaton complained to Bostock that intelligence from British Pacific Fleet concerning its ships' movements eastwards out of Western Area was hours out of date by the time it was received at Southern Area Command, leading to RAAF aircraft missing their rendezvous and wasting valuable flying hours searching empty ocean. There had been no U-boat strikes since February, and by June the naval authorities indicated that there was no pressing need for air cover except for the most important vessels.[36]

Post-war career and legacy

Eaton retired from the RAAF on 31 December 1945.[8] In recognition of his war service, he was appointed a Commander of the Order of Orange-Nassau with Swords by the Dutch government on 17 January 1946.[37] The same month, he became Australian consul in Dili. He had seen an advertisement for the position and was the only applicant with experience of the area. While based there, he accompanied the provincial governor on visits to townships damaged in Allied raids during the war, taking care to be circumspect about the part played by his own forces from No. 79 Wing.[38] In July 1947, Dutch forces launched a "police action" against territory held by the fledgling Indonesian Republic, which had been declared shortly after the end of the war. Following a ceasefire, the United Nations set up a commission, chaired by Eaton as Consul-General, to monitor progress. Eaton and his fellow commissioners believed that the ceasefire was serving the Dutch as a cover for further penetration of republican enclaves. His requests to the Australian government for military observers led to deployment of the first peacekeeping force to the region; the Australians were soon followed by British and US observers, and enabled Eaton to display a more realistic impression of the situation to the outside world. The Dutch administration strongly opposed the presence of UN forces and accused Eaton of "impropriety", but the Australian government refused to recall him.[39] Following the transfer of sovereignty in December 1949, he became Australia's first secretary and chargé d'affaires to the Republic of the United States of Indonesia.[38] In 1950, he returned to Australia to serve with the Department of External Affairs in Canberra.[1] After retiring from public service in 1951, he and his wife farmed at Metung, Victoria, and cultivated orchids.[38][40] They later moved to Frankston, where Eaton was involved in promotional work.[1]

Charles Eaton died in Frankston on 12 November 1979. Survived by his wife and two sons, he was cremated. In accordance with his wishes, his ashes were scattered near Tennant Creek, site of his 1929 forced landing during the search for the Kookaburra, from an RAAF Caribou on 15 April 1981.[3][40] His name figures prominently in the Northern Territory, commemorated by Lake Eaton in Central Australia, Eaton Place in the Darwin suburb of Karama, Charles Eaton Drive on the approach to Darwin International Airport, and the Charles Moth Eaton Saloon Bar in the Tennant Creek Goldfields Hotel. He is also honoured with a display at the Northern Territory Parliament, and a National Trust memorial at Tennant Creek Airport.[6] At the RAAF's 2003 History Conference, Air Commodore Mark Lax, recalling Eaton's search-and-rescue missions between the wars, commented: "Today, we might think of Eaton perhaps as the pioneer of our contribution to assistance to the civil community—a tradition that continues today. Perhaps I might jog your memory to a more recent series of rescues no less hazardous for all concerned—the amazing location of missing yachtsmen Thierry Dubois, Isabelle Autissier and Tony Bullimore by our P-3s that guided the Navy to their eventual rescue. My observation is that such activities remain vital for our relevance in that we must remain connected, supportive and responsive to the wants and needs of the Australian community."[12]

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "Eaton, Charles (1895–1979)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Williamson, Mitch (2002). "'Moth' Eaton: From Trench to Sky". Cross and Cockade. Vol. 33. pp. 104–110.

- 1 2 Kelton, Group Captain Mark (23 March 2006). "Remembered: Darwin's man of action". Air Force News. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ↑ "P03531.004". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 Grose, An Awkward Truth, p. 51

- 1 2 3 4 Farram, Charles "Moth" Eaton, pp. 1–3

- ↑ Alexander, Who's Who in Australia 1950, p. 235

- 1 2 "Eaton, Charles". World War 2 Nominal Roll. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ↑ Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, p. 404

- ↑ "East-West Air Race Ends". The Age. 7 October 1929. Archived from the original on 15 September 2009. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, pp. 297–303

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Lax, 100 Years of Aviation, p. 81

- 1 2 Farram, Charles "Moth" Eaton, pp. 4–12

- ↑ Farram, Charles "Moth" Eaton, pp. 13–17

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 33697. p. 1648. 10 March 1931. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ↑ Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, p. 268

- ↑ Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, p. 450

- ↑ Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, pp. 342–344

- 1 2 Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, pp. 145–148

- ↑ Farram, Charles "Moth" Eaton, p. 22

- 1 2 3 4 Gillison, Royal Australian Air Force 1939–1942, pp. 125–126

- ↑ RAAF Historical Section, Units of the Royal Australian Air Force, p. 5

- 1 2 Farram, Charles "Moth" Eaton, p. 27

- ↑ Wilson, The Brotherhood of Airmen, pp. 36–37

- ↑ Farram, Charles "Moth" Eaton, p. 31

- ↑ Farram, Charles "Moth" Eaton, p. 36

- ↑ Stephens, The Royal Australian Air Force, p. 136

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 35399. p. 13. 1 January 1942. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ↑ Odgers, Air War Against Japan, pp. 114–115

- ↑ Farram, Charles "Moth" Eaton, p. 38

- 1 2 3 4 Odgers, Air War Against Japan, pp. 215–218

- 1 2 Farram, Charles "Moth" Eaton, pp. 48–49

- ↑ Odgers, Air War Against Japan, pp. 243–244

- ↑ Recommendation: Mention in Dispatches at Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 36975. p. 1326. 9 March 1945. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ↑ Odgers, Air War Against Japan, pp. 351–354

- ↑ "Award: Dutch Order of Orange-Nassau – Commander". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 Farram, Charles "Moth" Eaton, pp. 52–53

- ↑ RAAF, The Australian Experience of Air Power, pp.142–143

- 1 2 Farram, Charles "Moth" Eaton, pp. 54–55

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles Eaton (RAAF officer). |

- Alexander, Joseph A. (ed.) (1950). Who's Who in Australia 1950. Melbourne: Colorgravure. OCLC 458407057.

- Coulthard-Clark, Chris (1991). The Third Brother: The Royal Australian Air Force 1921–39. North Sydney: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 0-04-442307-1.

- Farram, Steven (2007). Charles "Moth" Eaton: Pioneer Aviator of the Northern Territory. Darwin: Charles Darwin University Press. ISBN 978-0-9803846-1-1.

- Gillison, Douglas (1962). Australia in the War of 1939–1945: Series Three (Air) Volume I – Royal Australian Air Force 1939–1942. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 2000369.

- Grose, Peter (2009). An Awkward Truth: The Bombing of Darwin, February 1942. Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74175-643-2.

- Lax, Air Commodore Mark (4–5 August 2003). Wing Commander Keith Brent, ed. Key Events in RAAF History. 100 Years of Aviation: The Australian Military Experience – The Proceedings of the 2003 RAAF History Conference. Fairbairn, Australian Capital Territory: The Aerospace Centre. ISBN 0-642-26587-9.

- Odgers, George (1968) [1957]. Australia in the War of 1939–1945: Series Three (Air) Volume II – Air War Against Japan 1943–1945. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 246580191.

- RAAF Historical Section (1995). Units of the Royal Australian Air Force: A Concise History. Volume 1: Introduction, Bases, Supporting Organisations. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. ISBN 0-644-42792-2.

- Royal Australian Air Force (2008). The Australian Experience of Air Power (PDF). Tuggeranong, Australian Capital Territory: Air Power Development Centre. ISBN 1-920800-14-X.

- Stephens, Alan (2006) [2001]. The Royal Australian Air Force: A History. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-555541-4.

- Wilson, David (2005). The Brotherhood of Airmen. Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-74114-333-0.