Electric Smelting and Aluminum Company

| Private | |

| Industry | Aluminum, bronze, carborundum, copper, alloys |

| Founded | c. 1886 to 1940s |

| Founder | Alfred H. Cowles, Eugene H. Cowles |

| Headquarters |

555 Jackson Street, Lockport, New York, United States—before 1895, the Cowles Electric Smelting and Aluminum Company Cowles Syndicate Company, Limited, Staffordshire, England |

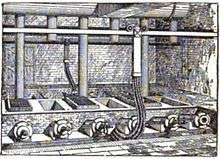

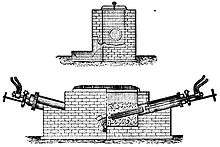

The Electric Smelting and Aluminum Company, founded as Cowles Electric Smelting and Aluminum Company, and Cowles Syndicate Company, Limited, formed in the United States and England during the mid-1880s to extract and supply valuable metals. Founded by two brothers from Ohio, the Cowles companies are remembered for producing alloys in quantity sufficient for commerce. Their furnaces were electric arc smelters, one of the first viable methods for extracting metals.

The businesses of the era dramatically increased the supply of aluminium, a plentiful resource not found in nature in pure form, and reduced its price. The Cowles process was the immediate predecessor to the Hall-Héroult process—today in nearly universal use more than a century after it was discovered by Charles Martin Hall and Paul Héroult and adapted by others including Carl Josef Bayer. Because of the patent landscape, the Cowles companies found themselves in court. Judges eventually acknowledged their innovations many years after the companies formed, and one brother received two separate settlements.[1]

Early years

Eugene H. Cowles and Alfred H. Cowles, sons of newspaper publisher Edwin Cowles of Cleveland, Ohio, built high temperature furnaces during the late 1880s in Lockport, New York and in Stoke-upon-Trent in England based on the furnace of Carl Wilhelm Siemens. Charles F. Mabery, at the time of what is today the Case School of Engineering, contributed expertise in chemistry.[2][3]

The family had purchased a copper zinc mine on the Pecos River in New Mexico in 1883. Eugene that year designed a furnace to extract zinc from the mine's ores. Two young employees were testing four furnaces in a Cleveland laboratory by 1885.[4] Their first plant was built to extract aluminium, in 1886 using hydropower from a tailrace of Niagara Falls on the Niagara River.[5]

Adolphe Minet wrote a sympathetic assessment twenty years later in 1905 from the perspective of Paris. The Cowles furnace was electrochemical, one of two kinds of processes applied to producing aluminum during the 19th century, and belonged to the electrothermic group that includes Héroult (alloys), Brin, Bessemer, Stephanite and Moissan (carbide). Minet thought Cowles was the first great advance in electrometallurgy at least for many years, calling it a "practical" furnace yielding alloy up to 20 percent aluminum. The first was begun in 1884 and the best was tested in Cleveland in 1886. Minet gave the real credit though to other chemists who saw how to produce "pure aluminum".[6]

William Frishmuth, who as the sole aluminium supplier in the United States built the Washington Monument's aluminum cap in 1884, was one among those who worried that "foreign capitalists" were about to control the world aluminium market.[7]

Charles Martin Hall was a graduate of Oberlin College in Ohio who had discovered in February 1886 an electrolytic process for aluminum extraction. His patent application in July collided with Paul Héroult's application for the same idea, "electrolysis of alumina in cryolite" and for which Héroult had received the patent in France in April. Hall proved his February date and was awarded the patent in the U.S.[3] Hall made a licensing agreement and worked with the Cowles at the facility in Lockport with the hopes of moving his ideas from the laboratory into production.

Cowles did not choose to use the Hall patent.[8] Their reason is unclear—some in Lockport remember it as disagreement about "external heat and copper electrodes" and "internally heated furnace and carbon electrodes",[9] and Alcoa culture remembers it as an attempt to "suppress his new process by buying him out".[10] Hall left after one year, in July 1888, to found the Pittsburgh Reduction Company which today is named Alcoa.[8]

Later years

In 1891 after Cowles began to advertise "pure aluminum" they were sued by the Pittsburgh Reduction Company. The judge announced his decision in January 1893, finding them to be infringing the patent of Hall and having gained knowledge of his process by hiring away a chemist named Hobbs who was the foreman in Pittsburgh.[8][11] In 1903 the Cowles won a countersuit. The surviving brother Alfred chose to stop work on aluminum and Cowles received royalties and a US$1.35 million payment in settlement. The appeal said the patent application of Charles S. Bradley which Cowles had acquired in 1885 and Alcoa had acquired from Cowles in 1904 hinted at an internally rather than externally heated furnace.[12][13]

The Cowles facility in England became part of British Aluminium in the late 1880s. In 1893, after Eugene's death, Maybery questioned a presentation that to him indicated the Cowles patents were infringed by the carborundum process of Edward Acheson (Acheson process). In 1900 Cowles received a $300,000 payment from the carborundum company.[12] The judges' decision gave "priority broadly to the Messrs. Cowles for reducing ores and other substances by the incandescent method".[14]

Influence

The achievements of Hall in the U.S. and of Héroult in Europe, and their influence on aluminum companies, some through Héroult's Société Electrometallurgique Française, have been called one of the greatest events in metallurgy.[5] Over ten years, aluminum output in the U.S. increased by 100,000 times and its price dropped to about 2% of its cost before their discovery.[15][16] Cowles engineered a separate venture and did not share that glory, but sometimes the brothers are credited with envisioning and promoting what was the beginning of electrical smelting on a large scale.[5]

Notes

- ↑ Donald Holmes Wallace (1977) [1937]. Market Control in the Aluminum Industry. Harvard University Press via Ayer Publishing via Google Books limited view. p. 6. ISBN 0-405-09786-7. Retrieved 2007-10-27.

- ↑ US patent 324658, Eugene H. Cowles and Alfred H. Cowles, "Electric process of smelting ore for the production of alloys, bronzes, and metallic compounds", issued 1885-08-18 and US patent 324659, Eugene H. Cowles, Charles F. Mabery and Alfred H. Cowles, "Process of electric smelting for obtaining aluminium", issued 1885-08-18 and US patent 464933, Charles S. Bradley, "Process of Obtaining Metals From Their Ores or Compounds by Electrolysis, acquired by Cowles", issued 1891-12-08

- 1 2 Overview courtesy Meiers, Peter. "Manufacture of Aluminum". Retrieved 2007-10-25.

- ↑ American Association for the Advancement of Science (1886). "Proceedings, Thirty-Fourth Meeting, Held at Ann Arbor, Mich. (1885)". 34. The Permanent Secretary, via a Google Books scan of a University of Michigan copy. Retrieved 2007-10-28.

- 1 2 3 Leonard Waldo (translator, additions) in Minet, Adolphe (1905). Aluminum in the United States, in The Production of Aluminum and Its Industrial Use. New York, London: John Wiley and Sons, Chapman & Hall, via Google Books scan of University of Wisconsin - Madison copy. pp. 241–256. Retrieved 2007-10-28.

- ↑ Minet, Adolphe (1905). The Production of Aluminum and Its Industrial Use. Leonard Waldo (translator, additions). New York, London: John Wiley and Sons, Chapman & Hall, via Google Books scan of University of Wisconsin - Madison copy. pp. 1+22–27+65+79+116 (Héroult speaking)+149. Retrieved 2007-10-28.

- ↑ Binczewski quotes Frishmuth from a 25 November 1884 article in The New York Times. Binczewski, George J. (1995). "The Point of a Monument: A History of the Aluminum Cap of the Washington Monument". JOM. The Minerals, Metals & Materials Society via tms.org. 47 (11): 20–25. doi:10.1007/bf03221302. Retrieved 2007-10-27.

- 1 2 3 "Charles Martin Hall (1863-1914), Collection, 1882-1985, Biography". Oberlin College Archives. 1 November 1994. Retrieved 2007-10-28.

- ↑ Journal of the Electrochemical Society U.S. (1948) 105 (7) via a single Google Books snippet, "Hall, who, after 1889, gave up external heating of graphite-lined iron pots and used the current alone to keep the bath fused", and Rooney, Bob (ed.). "Lockport's Points Of Pride". Lockport-NY.com. Retrieved 2007-10-28.

- ↑ Ackerman, Laurence D. (1 March 2000). Identity Is Destiny: Leadership and the Roots of Value Creation. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, via Amazon Online Reader Search Inside. p. 24. ISBN 1-57675-068-X. Retrieved 2007-10-28.

- ↑ "Against the Cowles Company, Decision in the Aluminium Patent Infringment Case (article preview)". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. 15 January 1893. Retrieved 2007-10-28.

- 1 2 Sackett, William Edgar, John James Scannell and Mary Eleanor Watson (1917/1918). New Jersey's First Citizens. New Jersey: J.J. Scannell via Google Books scan of New York Public Library copy. pp. 103–105. Retrieved 2007-10-25. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ McMillan, Walter George (1891). A Treatise on Electro-Metallurgy. London, Philadelphia: Charles Griffin and Company, J.B. Lippincott Company, via Google Books scan of New York Public Library copy. pp. 302–305. Retrieved 2007-10-26.

- ↑ Mabery, Charles F. (1900). "Notes, On Carborundum". Journal of the American Chemical Society. Johnson Reprint Company, via Google Books scan of Harvard University copy. XXII (Part II): 706–707. doi:10.1021/ja02048a014. Retrieved 2007-10-28.

- ↑ Minet, Adolphe (1905). Appendixes C and D, The Production of Aluminum and Its Industrial Use. Leonard Waldo (translator, additions). New York, London: John Wiley and Sons, Chapman & Hall, via Google Books scan of University of Wisconsin - Madison copy. pp. 253–254. Retrieved 2007-10-28.

- ↑ "Aluminum, Industry of the Future (annual report)" (PDF). United States Department of Energy,. 2004. pp. 8+12. Retrieved 2007-10-27.

Further reading

- "Cowles' Aluminium Alloys". The Manufacturer and Builder. New York: Western and Company, via Cornell University Library. 18 (1): 13. January 1886. Retrieved 2007-10-27.

- "The Cowles Electric Smelting Furnace". The Manufacturer and Builder. New York: Western and Company, via Cornell University Library. 18 (2): 40–42. February 1886. Retrieved 2007-10-27.

- "The Cowles Electric Smelting Furnace". The Manufacturer and Builder. New York: Western and Company, via Cornell University Library. 18 (3): 64–65. March 1886. Retrieved 2007-10-27.

- "The Cowles Mammoth Dynamo". The Manufacturer and Builder. New York: Western and Company, via Cornell University Library. 20 (10): 229. October 1888. Retrieved 2007-10-27.

External links

- "Photo of the company courtesy Lockport Secondary Sights". Lockport-NY.com. Retrieved 2007-10-27.