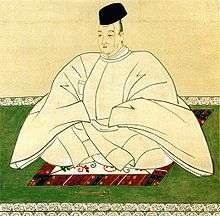

Emperor Kōkaku

| Kōkaku | |

|---|---|

| Emperor of Japan | |

Kōkaku | |

| Reign | 1780–1817 |

| Predecessor | Go-Momozono |

| Successor | Ninkō |

| Born | 23 September 1771 |

| Died | 11 December 1840 (aged 69) |

| Burial | Nochi no tsuki no wa no misasagi (Kyoto) |

| Father | Prince Kan'in-no-miya Sukehito-shinnō |

| Religion | Shinto |

Emperor Kōkaku (光格天皇 Kōkaku-tennō, September 23, 1771 – December 11, 1840) was the 119th emperor of Japan,[1] according to the traditional order of succession.[2]

Kōkaku's reign spanned the years from 1780 through 1817.[3] As of 2016, Kōkaku remains the most recent emperor of Japan to have abdicated from the throne.

Events of Kōkaku's life

He reigned from December 16, 1779, until May 7, 1817.

As a younger son of an imperial collateral branch the Kan'in house, it was originally expected that he (then called Tomohito-shinnō) would go into the priesthood at the Shugoin Temple. However, in 1779, the sonless and dying emperor Go-Momozono hurriedly adopted him on his deathbed.

Kōkaku was very talented and had a zeal for scholarship, reviving festivals at the Iwashimizu and Kamono shrines, and working hard at reviving ceremonies surrounding the Imperial Court. The Bakufu gave his father the honorary title of Retired Emperor (Daijō Tennō, 太上天皇). Genealogically, Kōkaku is the founder of the dynastic imperial branch currently on the throne. Kōkaku is the lineal ancestor of all the succeeding emperors of Japan up to present monarch, Akihito.

During Kōkaku's reign, the Imperial Court attempted to re-assert some of its authority by proposing a relief program to the Bakufu at the time of the Great Tenmei famine (1782–1788) and receiving information about negotiations with Russia over disputes in the north.

- 1781 (Tenmei 1): Kōkaku was instrumental in reviving old ceremonies involving the old Imperial Court, as well as those performed at the Iwashimizu and Kamono shrines.

In addition, he attempted to re-assert some of the Imperial authority over the Shōgun (or bakufu). He undertook this by first implementing a relief program during the Great Tenmei Famine, which not only undermined the effectiveness of the bakufu to look after their subjects, but also focused the subjects' attention back to the Imperial household.

He also took an active interest in foreign affairs; keeping himself informed about the border dispute with Russia to the north, as well as keeping himself abreast of knowledge regarding foreign currency, both Chinese and European. The new era name of Tenmei (meaning "Dawn") was created to mark the enthronement of new emperor. The previous era ended and the new one commenced in An'ei 11, on the 2nd day of the 4th month.

- 1782 (Tenmei 2): Great Tenmei famine begins.

- 1782 (Tenmei 2): An analysis of silver currency in China and Japan "Sin sen sen pou (Sin tchuan phou)" was presented to the emperor by Kutsuki Masatsuna (1750–1802), also known as Kutsuki Oki-no kami Minamoto-no Masatsuna, hereditary daimyo of Oki and Ōmi with holdings in Tamba and Fukuchiyama – related note at Tenmei 7 below.[4]

- 1783 (Tenmei 3): Mount Asama (浅間山, Asama-yama) erupted in Shinano, one of the old provinces of Japan. (Today, Asama-yama's location is better described as on the border between Gunma and Nagano prefectures.) Japanologist Isaac Titsingh's published account of the Asama-yama eruption will become first of its kind in the West (1820).[5] The volcano's devastation makes the Great Tenmei Famine even worse.

- 1784 (Tenmei 4): Country-wide celebrations in honor of Kūkai (also known as Kōbō-Daishi, 弘法大師), founder of Shingon Buddhism) who died 950 years earlier.[4]

- September 17, 1786 (Tenmei 6, 15th day of the 8th month): Tokugawa Ieharu died and was buried in Edo.[4]

- 1787 (Tenmei 7): Kutsuki Masatsuna published Seiyō senpu (Notes on Western Coinage), with plates showing European and colonial currency – related note at Tenmei 2 above.[6] – see online image of 2 adjacent pages from library collection of Kyoto University of Foreign Studies and Kyoto Junior College of Foreign Languages

- 1788 (Tenmei 8): Great Tenmei fire. A fire in the city of Kyoto, which began at 3 o'clock in the morning of the 29th day of the 1st month of Tenmei 8 (March 6, 1788), continued to burn uncontrolled until the 1st day of the second month (March 8); and embers smoldered until they were extinguished by heavy rain on the 4th day of the second month (March 11). The emperor and his court fled the fire, and the Imperial Palace was destroyed. No other re-construction was permitted until a new palace was completed. This fire was considered a major event. The Dutch VOC Opperhoofd in Dejima noted in his official record book that "people are considering it to be a great and extraordinary heavenly portent."[7]

Change of era: 1789 Kansei gannen (寛政元年?): The new era name of Kansei (meaning "Tolerant Government" or "Broad-minded Government") was created to mark a number of calamities including a devastating fire at the Imperial Palace. The previous era ended and a new one commenced in Tenmei 9, on the 25th day of the 1st month.

The broad panoply of changes and new initiatives of the Tokugawa shogunate during this era became known as the Kansei Reforms.

Matsudaira Sadanobu (1759–1829) was named the shogun's chief councilor (rōjū) in the summer of 1787; and early in the next year, he became the regent for the 11th shogun, Tokugawa Ienari.[8] As the chief administrative decision-maker in the bakufu hierarchy, he was in a position to effect radical change; and his initial actions represented an aggressive break with the recent past. Sadanobu's efforts were focused on strengthening the government by reversing many of the policies and practices which had become commonplace under the regime of the previous shogun, Tokugawa Ieharu. These reform policies could be interpreted as a reactionary response to the excesses of his rōjū predecessor, Tanuma Okitsugu (1719–1788);[9] and the result was that the Tanuma-initiated, liberalizing reforms within the bakufu and the relaxation of sakoku (Japan's "closed-door" policy of strict control of foreign merchants) were reversed or blocked.[10]

- 1790 (Kansei 2): Matsudaira Sadanobu and the shogunate promulgate an edict addressed to Hayashi Kinpō, the rector of the Edo Confucian Academy -- "The Kansei Prohibition of Heterodox Studies" (kansei igaku no kin).[11] The decree banned certain publications and enjoined strict observance of Neo-Confucian doctrine, especially with regard to the curriculum of the official Hayashi school.[12]

- 1798 (Kansei 10): Kansei Calendar Revision

Change of era: February 5, 1801 (Kyōwa gannen (享和元年?)): a new era name was created because of the belief that the 58th year of every cycle of the Chinese zodiac brings great changes. The previous era ended and a new one commenced in Kansei 13.

- December 9, 1802 (Kyōwa 2, 15th day of the 11th month): Earthquake in northwest Honshū and Sado Island (Latitude: 37.700/Longitude: 138.300), 6.6 magnitude on the Richter Scale.[13]

- December 28, 1802 (Kyōwa 2, 4th day of the 12th month): Earthquake on Sado Island (Latitude: 38.000/Longitude: 138.000).[13]

Change of era: February 11, 1804 (Bunka gannen (文化元年?)): The new era name of Bunka (meaning "Culture" or "Civilization") was created to mark the start of a new 60-year cycle of the Heavenly Stem and Earthly Branch system of the Chinese Calendar which was on New Year's Day, the new moon day day of 2 November 1804. The previous era ended and a new one commenced in Kyōwa 4.

- 1804 (Bunka 1): Daigaku-no kami Hayashi Jussai (1768–1841) explained the shogunate foreign policy to Emperor Kōkaku in Kyoto.[14]

- June 1805 (Bunka 2): Genpaku Sugita (1733–1817) is granted an audience with Shogun Ienari to explain differences between traditional medical knowledge and Western medical knowledge.[15]

- September 25, 1810 (Bunka 7, 27th day of the 8thmonth): Earthquake in northern Honshū (Latitude: 39.900/Longitude: 139.900), 6.6 magnitude on the Richter Scale.[13]...Click link for NOAA/Japan: Significant Earthquake Database

- December 7, 1812 (Bunka 9, 4th day of the 11th month): Earthquake in Honshū (Latitude: 35.400/Longitude: 139.600), 6.6 magnitude on the Richter Scale.[13]

- 1817 (Bunka 14): Emperor Kokaku travelled in procession to Sento Imperial Palace, a palace of an abdicated emperor. The Sento Palace at that time was called Sakura Machi Palace. It had been built by the Tokugawa Shogunate for former-Emperor Go-Mizunoo.[16]

In 1817, Kōkaku abdicated in favor of his son, Emperor Ninkō. In the two centuries before Kōkaku's reign most emperors died young or were forced to abdicate. Kōkaku was the first Japanese monarch to remain on the throne past the age of 40 since the abdication of Emperor Ōgimachi in 1586.

The last Emperor to rule as a Jōkō (上皇), an emperor who abdicated in favor of a successor, was Emperor Kōkaku (1779–1817). The Emperor later created an incident called the "Songo incident" (the "respectful title incident"). The emperor came into dispute with the Tokugawa Shogunate about his intention to give a title of Abdicated Emperor (Daijō-ten'nō) to his father, who was an Imperial Prince Sukehito.[17]

After Kōkaku's death in 1840, he was enshrined in the Imperial mausoleum, Nochi no Tsukinowa no Higashiyama no misasagi (後月輪東山陵), which is at Sennyū-ji in Higashiyama-ku, Kyoto. Also enshrined in Tsuki no wa no misasagi, at Sennyū-ji are this emperor's immediate Imperial predecessors since Emperor Go-Mizunoo – Meishō, Go-Kōmyō, Go-Sai, Reigen, Higashiyama, Nakamikado, Sakuramachi, Momozono, Go-Sakuramachi and Go-Momozono. This mausoleum complex also includes misasagi for Kōkaku's immediate successors – Ninkō and Kōmei.[18] Empress Dowager Yoshikō is also entombed at this Imperial mausoleum complex.[19]

Kugyō

Kugyō (公卿) is a collective term for the very few most powerful men attached to the court of the Emperor of Japan in pre-Meiji eras. Even during those years in which the court's actual influence outside the palace walls was minimal, the hierarchic organization persisted.

In general, this elite group included only three to four men at a time. These were hereditary courtiers whose experience and background would have brought them to the pinnacle of a life's career. During Kōkaku's reign, this apex of the Daijō-kan included:

- Sesshō, Kujō Naozane, 1779–1785

- Kampaku, Kujō Naozane, 1785–1787

- Kampaku, Takatsukasa Sukehira, 1787–1791

- Kampaku, Ichijō Teruyoshi, 1791–1795

- Kampaku, Takatsukasa Masahiro, 1795–1814

- Kampaku, Ichijō Tadayoshi, 1814–1823

- Sadaijin

- Udaijin

- Naidaijin

- Dainagon

Eras of Kōkaku's reign

The years of Kōkaku's reign are more specifically identified by more than one era name or nengō.[4]

See also

- Emperor of Japan

- List of Emperors of Japan

- Imperial cult

- Imperial House of Japan

- Modern system of ranked Shinto shrines

Notes

- ↑ Imperial Household Agency (Kunaichō): 光格天皇 (119)

- ↑ Ponsonby-Fane, Richard. (1959). The Imperial House of Japan, pp. 120–122.

- ↑ Titsingh, Isaac. (1834). Annales des empereurs du japon, pp. 420–421.

- 1 2 3 4 Titsingh, p. 420.

- ↑ Screech, T. (2006), Secret Memoirs of the Shoguns: Isaac Titsingh and Japan, 1779–1822, pp. 146–148; Titsingh, p. 420.

- ↑ Screech, T. (2000). Shogun's Painted Culture: Fear and Creativity in the Japanese States, 1760–1829, pp. 123, 125.

- ↑ Screech, Secret Memoirs, pp. 152–154, 249–250

- ↑ Totman, Conrad. Politics in the Tokugawa Bakufu. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988, p. 224

- ↑ Hall, J. (1955). Tanuma Okitsugu: Forerunner of Modern Japan, 1719-1788. pp. 131-142.

- ↑ Screech, T. (2006). Secret Memoirs of the Shoguns: Isaac Titsingh and Japan, 1779-1822, pp. 148-151, 163-170, 248.

- ↑ Nosco, Peter. (1997). Confucianism and Tokugawa Culture, p. 20.

- ↑ Bodart-Bailey, Beatrice. (2002). "Confucianism in Japan," in Companion Encyclopedia of Asian Philosophy, p. 668, p. 668, at Google Books; excerpt, "Scholars vary in their opinion on how far this heterodoxy was enforced and whether this first official insistence on heterodoxy constituted the high point of Confucianism in government affairs or signalled its decline."

- 1 2 3 4 NOAA/Japan "Significant Earthquake Database" -- U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), National Geophysical Data Center (NGDC)

- ↑ Cullen, L.M. (2003). A History of Japan, 1582-1941: Internal and External Worlds, pp. 117, 163.

- ↑ Sugita Genpaku. (1969). Dawn of Western Science in Japan: Rangaku Kotohajime, p. xvi.

- ↑ National Ditigial Archives of Japan, ...see caption describing image of scroll

- ↑ National Archives of Japan ...Sakuramachiden Gyokozu: see caption text

- ↑ Ponsonby-Fane, p. 423.

- ↑ Ponsonby-Fane, pp. 333–334.

References

- Meyer, Eva-Maria. (1999). Japans Kaiserhof in der Edo-Zeit: unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Jahre 1846 bis 1867. Münster: LIT Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8258-3939-0; OCLC 42041594

- Ponsonby-Fane, Richard Arthur Brabazon. (1959). The Imperial House of Japan. Kyoto: Ponsonby Memorial Society. OCLC 194887

- Screech, Timon. (2006). Secret Memoirs of the Shoguns: Isaac Titsingh and Japan, 1779–1822. London: RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 978-0-203-09985-8; OCLC 65177072

- __________. (2000). Shogun's Painted Culture: Fear and Creativity in the Japanese States, 1760–1829. London: Reaktion. IBN 9781861890641; OCLC 42699671

- Titsingh, Isaac. (1834). Nihon Ōdai Ichiran; ou, Annales des empereurs du Japon. Paris: Royal Asiatic Society, Oriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland. OCLC 5850691

- Varley, H. Paul. (1980). Jinnō Shōtōki: A Chronicle of Gods and Sovereigns. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-04940-5; OCLC 59145842

External links

- National Archives of Japan: Sakuramachiden Gyokozu, scroll depicting Emperor Kōkaku in formal procession, 1817 (Bunka 14).

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Emperor Go-Momozono |

Emperor of Japan: Kōkaku 1780–1817 |

Succeeded by Emperor Ninkō |