Corneal endothelium

| Corneal endothelium | |

|---|---|

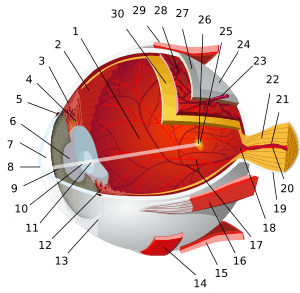

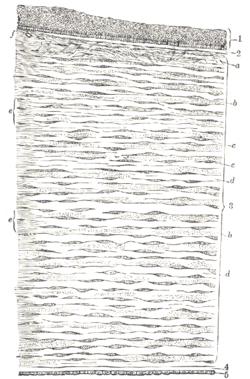

Vertical section of human cornea from near the margin. (Corneal endothelium is #5, labeled at bottom right.) | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | epithelium posterius corneae |

| TA | A15.2.02.022 |

| FMA | 63882 |

The corneal endothelium is a single layer of cells on the inner surface of the cornea. It faces the chamber formed between the cornea and the iris.

The corneal endothelium are specialized, flattened, mitochondria-rich cells that line the posterior surface of the cornea and face the anterior chamber of the eye. The corneal endothelium governs fluid and solute transport across the posterior surface of the cornea and actively maintains the cornea in the slightly dehydrated state that is required for optical transparency.

Embryology and anatomy

The corneal endothelium is embryologically derived from the neural crest. The postnatal total endothelial cellularity of the cornea (approximately 300,000 cells per cornea) is achieved as early as the second trimester of gestation. Thereafter the endothelial cell density (but not the absolute number of cells) rapidly declines, as the fetal cornea grows in surface area,[1] achieving a final adult density of approximately 2400 - 3200 cells/mm². The number of endothelial cells in the fully developed cornea decreases with age up until early adulthood, stabilizing around 50 years of age.[2]

The normal corneal endothelium is a single layer of uniformly sized cells with a predominantly hexagonal shape. This honeycomb tiling scheme yields the greatest efficiency, in terms of total perimeter, of packing the posterior corneal surface with cells of a given area. The corneal endothelium is attached to the rest of the cornea through Descemet's membrane, which is an acellular layer composed mostly of collagen.

Physiology

The principal physiological function of the corneal endothelium is to allow leakage of solutes and nutrients from the aqueous humor to the more superficial layers of the cornea while at the same time actively pumping water in the opposite direction, from the stroma to the aqueous. This dual function of the corneal endothelium is described by the "pump-leak hypothesis." Since the cornea is avascular, which renders it optimally transparent, the nutrition of the corneal epithelium, stromal keratocytes, and corneal endothelium must occur via diffusion of glucose and other solutes from the aqueous humor, across the corneal endothelium. The corneal endothelium then actively transports water from the stromal-facing surface to the aqueous-facing surface by an interrelated series of active and passive ion exchangers. Critical to this energy-driven process is the role of Na+/K+ATPase and carbonic anhydrase. Bicarbonate ions formed by the action of carbonic anhydrase are translocated across the cell membrane, allowing water to passively follow.

Mechanisms of corneal edema

Corneal endothelial cells are post-mitotic and divide rarely, if at all, in the post-natal human cornea. Wounding of the corneal endothelium, as from trauma or other insults, prompts healing of the endothelial monolayer by sliding and enlargement of adjacent endothelial cells, rather than mitosis. Endothelial cell loss, if sufficiently severe, can cause endothelial cell density to fall below the threshold level needed to maintain corneal deturgescence. This threshold endothelial cell density varies considerably amongst individuals, but is typically in the range of 500 - 1000 cells/mm². Typically, loss of endothelial cell density is accompanied by increases in cell size variability (polymegathism) and cell shape variation (polymorphism). Corneal edema can also occur as the result of compromised endothelial function due to intraocular inflammation or other causes. Excess hydration of the corneal stroma disrupts the normally uniform periodic spacing of Type I collagen fibrils, creating light scatter. In addition, excessive corneal hydration can result in edema of the corneal epithelial layer, which creates irregularity at the optically critical tear film-air interface. Both stromal light scatter and surface epithelial irregularity contribute to degraded optical performance of the cornea and can compromise visual acuity.

Causes of endothelial disease

Leading causes of endothelial failure include inadvertent endothelial trauma from intraocular surgery (such as cataract surgery) and Fuchs' dystrophy. Surgical causes of endothelial failure include both acute intraoperative trauma as well as chronic postoperative trauma, such as from a malpositioned intraocular lens or retained nuclear fragment in the anterior chamber. Other risk factors include narrow-angle glaucoma, aging, and iritis.

A rare disease called X-linked endothelial corneal dystrophy was described in 2006.

Treatment for endothelial disease

There is no medical treatment that can promote wound healing or regeneration of the corneal endothelium. In early stages of corneal edema, symptoms of blurred vision and episodic ocular pain predominate, due to edema and blistering (bullae) of the corneal epithelium. Partial palliation of these symptoms can sometimes be obtained through the instillation of topical hypertonic saline drops, use of bandage soft contact lenses, and/or application of anterior stromal micropuncture. In cases in which irreversible corneal endothelial failure develops, severe corneal edema ensues, and the only effective remedy is replacement of the diseased corneal endothelium through the surgical approach of corneal transplantation.

Historically, penetrating keratoplasty, or full thickness corneal transplantation, was the treatment of choice for irreversible endothelial failure. More recently, new corneal transplant techniques have been developed to enable more selective replacement of the diseased corneal endothelium. This approach, termed endokeratoplasty, is most appropriate for disease processes that exclusively or predominantly involve the corneal endothelium. Penetrating keratoplasty is preferred when the disease process involves irreversible damage not just to the corneal endothelium, but to other layers of the cornea as well. Compared to full-thickness keratoplasty, endokeratoplasty techniques are associated with shorter recovery times, improved visual results, and greater resistance to wound rupture. Although instrumentation and surgical techniques for endokeratoplasty are still in evolution, one commonly performed form of endokeratoplasty at present is Descemet's Stripping (Automated) Endothelial Keratoplasty (DSEK [or DSAEK]). In this form of endokeratoplasty, the diseased host endothelium and associated Descemet's membrane are removed from the central cornea, and in their place a specially harvested layer of healthy donor tissue is grafted. This layer consists of posterior stroma, Descemet's membrane, and endothelium that has been dissected from cadaveric donor corneal tissue, typically using a mechanized (or "automated") instrument.

Investigational methods of corneal endothelial surgical replacement include Descemet's Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty (DMEK), in which the donor tissue consists only of Descemet's membrane and endothelium, and corneal endothelial cell replacement therapy, in which in vitro cultivated endothelial cells are transplanted. These techniques, although still in an early developmental stage, aim to improve the selectivity of the transplantation approach by eliminating the presence of posterior stromal tissue from the grafted tissue.

References

- ↑ Murphy, C; Alvarado, J; Juster, R; Maglio, M (March 1984). "Prenatal and postnatal cellularity of the human corneal endothelium. A quantitative histologic study.". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 25 (3): 312–22. PMID 6698749.

- ↑ Wilson, R S; Roper-Hall, M J (1982). "Effect of age on the endothelial cell count in the normal eye.". British Journal of Ophthalmology. 66 (8): 513–515. doi:10.1136/bjo.66.8.513. PMC 1039838

. PMID 7104267.

. PMID 7104267.

Further reading

- Yanoff, Myron; Cameron, Douglas (2012). "Diseases of the Visual System". In Goldman, Lee; Schafer, Andrew I. Goldman's Cecil Medicine (24th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 2426–42. ISBN 978-1-4377-1604-7.