Financial costs of the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War inflicted great financial costs on all of the combatants, including the United States of America, France, Spain and Great Britain. France and Great Britain spent 1.3 billion livres and 250 million pounds, respectively. The United States spent $400 million in wages for its troops. Spain increased its military spending from 454 million reales in 1778 to over 700 million reales in 1779.

Economic warfare and financing

Initial boycotts

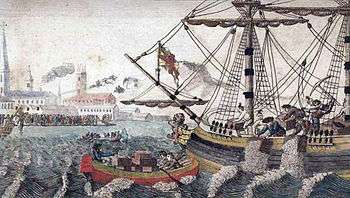

The economic warfare between Great Britain and the colonists began well before the colonies declared their independence in 1776. Regulations from the crown were met with fierce opposition from the colonists. After lobbies and petitions proved ineffective, the colonists turned to boycotting imported English goods. Boycotting proved to be successful in crippling British trade.[1] After the first colonial boycott in 1765, Parliament overturned the Sugar and Stamp Acts, and after a second boycott in 1768 Parliament overturned all of the Townshend duties except for the tax on tea.[2] The colonists persisted, and the American boycott on tea ultimately culminated in the Boston Tea Party of 1773. Despite the Revolution's widespread association with the colonists' aversion to higher taxes, it has been claimed that the colonists actually paid far less tax compared to their British counterparts.[3]

British isolation tactics

British efforts to weaken the colonies included isolating their economy from the rest of the world by cutting off trade. With a navy that was many times more powerful than its American counterpart, the English had virtual control over the American ports.[4] The British took control of major port cities along the colonial east coast, and as a result British warships were able to drastically reduce the number of ships that could successfully travel from the colonies. Consequently, the U.S. saw a fall in exported goods due to the relentless British blockade.[5] Furthermore, England’s naval strength was great enough to intimidate other nations and scare them away from exporting goods to the colonies, so smuggled and inexpensive imports became costly and rare.[6]

The American response

The Continental Army under the direction of George Washington sought to engage in a war of attrition.[7] Because the fight was on colonial soil, Washington aimed to take advantage of the lack of trade with Great Britain by cutting them off from necessary resources, hoping that eventually the redcoat army in North America would grow sick and tired. Under the Articles of Confederation, however, the Continental Congress did not have the power to impose taxes or regulate commerce in the colonies, and thus could not generate the sufficient funds for a war of attrition.[8]

To solve this problem, the Continental Congress sent diplomats including Benjamin Franklin to Europe in search of foreign support for the American cause. For the first two years of war, the colonists received secretive private and public loans from the French, who held a lingering resentment for the British after the Seven Years' War.[9] After the British defeat at Saratoga, however, foreign support for the Continental Army increased, and in 1778 the colonies signed a treaty with France, officially bringing them into the war with England.[10] By the end of the war, the colonies had received loans from several different European nations, including significant contribution from France, Spain and the Netherlands. In addition, the colonies received much private funding, most notably from the Marquis de Lafayette and the Baron of Kalb, both Frenchmen.[11] This funding ultimately enabled them to fight the war of attrition that General Washington hoped for.

The American Revolution effect on Great Britain

Because the French possessed a powerful navy, their entrance into the war weakened the British blockade on colonial ports and further cut off the British army from its Atlantic supply route.[12] The British forces recognized that they would not last long without shipping in supplies, so in retaliation, the British redeployed some of their forces to the French Caribbean. Their hope was to capture French sugar islands and cut the French financial supply line.[13] The new war in the Caribbean added to England’s already large financial costs, yet unlike the colonies, the British were not successful in their attempts to garner foreign loans or armaments. Without economic assistance from other nations, the financial strain on Parliament and British taxpayers became increasingly burdensome, and ultimately had a hand in wearing down the British forces and ending the war for independence.

American financing

As the war progressed, the Americans’ deteriorating financial stability quickly became Britain’s greatest asset. Because it did not possess the power to tax the colonists, the Continental Congress printed money at a rapid rate to fund the army’s expenses and pay off its loans from foreign nations.[14] As a result, the colonies experienced severe inflation and depreciation of the Continental dollar. The colonists also had great difficulty in financing a wartime effort against the British southern campaign, not effectively halting the British destruction until the battle of Yorktown in 1781. When war ended in 1783, American negotiations, monetary policies and government restructuring all contributed to paying off the American national debt.[15]

Belligerents

Great Britain

The American Revolutionary War took a heavy toll on Great Britain. The average cost for the war was £12 million a year. The British ended the war with a national debt of £250 million, which generated a yearly interest of over £9.5 million. This debt piled on to the already outstanding debt from the Seven Years' War. Taxes on the British population increased over the years and duties on some items such as glass and lead were also added, the average tax for the British public being four shillings in every pound.[16] Furthermore, the Royal Navy was not able to 'rule the waves' as it had done in the Seven Years' War.[17]

Great Britain's trade with the thirteen American colonies fell apart once the American Revolution started, causing British businessmen, especially from the tobacco industry, to suffer. Income from the sale of woolen and metal products dropped sharply and export markets dried up. British merchant sailors also felt the pinch: it is estimated that 3,386 British merchant ships were seized by enemy forces during the war.[18] However, Royal Navy warships did make up these losses somewhat, due to their own privateering efforts on enemy shipping, particularly Spanish and French merchant ships.

France

During the war, France shouldered a financial burden similar to that of Great Britain, as debt from the American Revolutionary War was piled upon already existing debts from the Seven Years' War. The French spent 1.3 billion livres on war costs. When the war ended, France had accumulated a debt of 3,315.1 million livres,[19] a fortune at the time.

The debt caused major economic and political problems for France, and, as the country struggled to pay its debts, eventually led to the Financial Crisis of 1786[20] and the French Revolution in 1789.[21]

Spain

Spain's economic losses were not as great as those of the other belligerents in the American Revolutionary War. This was because Spain paid off her debts quickly and efficiently. However, Spain had nearly doubled her military spending during the war, from 454 million reales in 1778 to over 700 million reales in 1779.[22] Spain's revenue loss was similar to Britain's, since she lost a lot of income from her American colonies due the war. To make up for the shortfall, Spanish governors introduced higher tax rates in the South American colonies, with little success. Spain's next move was to issue royal bonds to her colonies, also with limited success. Finally, in 1782 the first national bank of Spain – the Banco San Carlo – was created to improve and centralize the economic situation.

United States of America

For more details on the impact on the United States, see Economic history of the US.

The thirteen American states flourished economically at the beginning of the war.[23] The colonies could trade freely with the West Indies and other European nations, instead of just Britain. Due to the abolition of the British Navigation Acts, American merchants could now transport their goods in European and American ships rather than only British ships. British taxes on expensive wares such as tea, glass, lead and paper were forfeit, and other taxes became cheaper. Plus, American privateering raids on British merchant ships provided more wealth for the Continental Army.

As the war went on however, America's economic prosperity began to fall. British warships began to prey on American shipping, and the increasing upkeep costs of the Continental Army meant that wealth from merchant ships decreased. As cashflow declined, the United States of America had to rely on European loans to maintain the war effort; France, Spain and the Netherlands lent the United States over $10 million during the war, causing major debt problems for the fledgling nation. Coin circulation had also begun to wane. Because of this, the United States began to print paper money and bills of credit to raise income. This proved unsuccessful, inflation skyrocketed, and the new paper money's value diminished. A popular saying circulated the colonies because of this: anything of little value became "not worth a continental."[24]

By 1780, the United States Congress had issued over $400 million in paper money to troops. Eventually, Congress tried to stop the inflation by imposing economic reforms. These failed, and only further devalued the American currency.[25] Late in the war, Congress asked individual colonies to equip their own troops, and pay upkeep for their own soldiers in the Continental Army. When the war ended, the United States had spent $37 million at the national level and $114 million at the state level. The United States finally solved its debt problems in the 1790s when Alexander Hamilton founded the establishment of the First Bank of the United States.[26]

References

Notes

- ↑ Baack, 2001.

- ↑ Baack, 2001.

- ↑ Ferguson, p. 85

- ↑ Baack, 2001.

- ↑ "Economic Conditions During the War."

- ↑ "Economic Conditions During the War."

- ↑ Baack, 2001.

- ↑ Baack, 2001.

- ↑ "Economic Conditions During the War."

- ↑ Elson, 1904.

- ↑ Elson, 1904.

- ↑ Conway, 1995.

- ↑ Conway, 1995.

- ↑ Baack, 2001.

- ↑ Baack, 2001.

- ↑ Conway (1995) p. 189

- ↑ Marston (2002) p. 82

- ↑ Conway (1995) p. 191

- ↑ Conway (1995) p. 242

- ↑ Marston (2002) p. 82

- ↑ Tombs (2007) p. 179

- ↑ Lynch (1989) p. 326

- ↑ Marston (2002) p. 82

- ↑ "Not worth a continental", "Creating the United States", Library of Congress. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ↑ Marston (2002) p. 82

- ↑ Jensen (2004) p. 379

Bibliography

- Baack, Ben. "The Economics of the American Revolutionary War." EH.net Encyclopedia. Economic History Services, 13 Nov 2001. Web. 07 Mar 2013 <http://eh.net/encyclopedia/article/baack.war.revolutionary.us>.

- Conway, Stephen. The War of American Independence 1775–1783. Publisher: E. Arnold (1995) ISBN 0-340-62520-1. 280 pages.

- "Economic Conditions During the War." HistoryCentral.com. MultiEducator, Inc, n.d. Web. 13 Mar 2013. <http://www.historycentral.com/Revolt/Americans/During.html>.

- Elson, Henry William. "Foreign Aid." History of the United States of America. Kathy Leigh. New York: The MacMillan Company, 1904. 275-279. Web. <http://www.usahistory.info/Revolution/foreign-aid.html>.

- Ferguson, N. Empire: How Britain made the modern world. Publisher: Penguin Australia (2008). 422 pages.

- Jensen, Merrill. The Founding of a Nation: A History of the American Revolution 1763–1776. Hackett Publishing (2004) ISBN 978-0-87220-705-9. 735 pages

- Lynch, John. Bourbon Spain 1700—1808. Publisher: Oxford (1989) ISBN 978-0-631-19245-9. 450 pages.

- Marston, Daniel. The American Revolution 1774—1783. Osprey Publishing (2002) ISBN 978-1-84176-343-9. 95 pages.

- Tombs, Robert and Isabelle. That Sweet Enemy: The French and the British from the Sun King to the Present. Random House (2007) ISBN 978-1-4000-4024-7. 782 pages.