Kalmyk Khanate

| Kalmyk Khanate | ||||||||

| khanate | ||||||||

| ||||||||

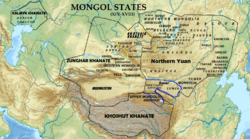

The Kalmyk Khanate in the 17th century. | ||||||||

| Capital | Not specified | |||||||

| Languages | Kalmyk language | |||||||

| Religion | Tibetan Buddhism | |||||||

| Government | Hereditary monarchy | |||||||

| President | ||||||||

| • | died 1644 | Kho Orluk | ||||||

| • | 1669–1724 | Ayuka Khan | ||||||

| History | ||||||||

| • | Established | 1630 | ||||||

| • | Annexed by Russia | 1771 | ||||||

| ||||||||

The Kalmyk Khanate was an Oirat khanate on the Eurasian steppe. It covered the area called Kalmykia and the surrounding areas stretching from Stavropol to Astrakhan. For over a hundred years the Kalmyk alternately raided the southern borderlands of Russia[1] but also protected southern borders of Russia and engaging in many military expeditions against the Muslim tribes of Central Asia, the North Caucasus and Crimea.[2] The Kalmyk conducted many military expeditions against the Crimean Tatars, Ottoman Empire and Kuban Tatars and also waged wars against the Kazakhs, subjugated the Mangyshlak Turkmens, and made multiple expeditions against the highlanders of the North Caucasus. The Khanate was annexed by the Russian Empire in 1771.

History

| History of the Mongols |

|---|

|

Timeline · History · Rulers · Nobility Culture · Language · Proto-Mongols |

|

|

|

Period of self-rule, 1630-1724

Upon arrival to the lower Volga region in 1630, the Oirats encamped on land that was once part of the Astrakhan Khanate, but was now claimed by the Tsarist government. The region was lightly populated, from south of Saratov to the Russian garrison at Astrakhan and on both the east and the west banks of the Volga River. The Tsarist government was not ready to colonize the area and was in no position to prevent the Oirats from encamping in the region. But it had a direct political interest in insuring that the Oirats would not become allied with its Turkic-speaking neighbors.

The Oirats quickly consolidated their position by expelling the majority of the native inhabitants, the Nogai Horde. Large groups of Nogais fled southeast to the northern Caucasian plain and west to the Black Sea steppe, lands claimed by the Crimean Khanate, itself a vassal or ally of Ottoman Turks. Smaller groups of Nogais sought the protection of the Russian garrison at Astrakhan. The remaining nomadic tribes became vassals of the Oirats.

At first, an uneasy relationship existed between the Russians and the Oirats. Mutual raiding by the Oirats of Russian settlements and by the Cossacks and the Bashkirs (Muslim vassals of the Russians) of Oirat encampments was commonplace. Numerous oaths and treaties were signed to ensure Oirat loyalty and military assistance. Although the Oirats became subjects of the Tsar, such allegiance by the Oirats was deemed to be nominal.

In reality, the Oirats governed themselves pursuant to a document known as the Great Code of the Nomads (Iki Tsaadzhin Bichig). The Code was promulgated in 1640 by them, their brethren in Dzungaria and some of the Eastern Mongols who all gathered near the Tarbagatai Mountains in Dzungaria to resolve their differences and to unite under the banner of the Gelugpa sect. Although the goal of unification was not met, the summit leaders did ratify the Code, which regulated all aspects of nomadic life.

In securing their position, the Oirats became a borderland power, often allying themselves with the Tsarist government against the neighboring Muslim population. During the era of Ayuka Khan, the Oirats rose to political and military prominence as the Tsarist government sought the increased use of Oirat cavalry in support of its military campaigns against the Muslim powers in the south, such as Persia, the Ottoman Empire, the Nogays and the Kuban Tatars and Crimean Khanate. Ayuka Khan also waged wars against the Kazakhs, subjugated the Mangyshlak Turkmens, and made multiple expeditions against the highlanders of the North Caucasus. These campaigns highlighted the strategic importance of the Kalmyk Khanate which functioned as a buffer zone, separating Russia and the Muslim world, as Russia fought wars in Europe to establish itself as a European power.

To encourage the release of Oirat cavalrymen in support of its military campaigns, the Tsarist government increasingly relied on the provision of monetary payments and dry goods to the Oirat Khan and the Oirat nobility. In that respect, the Tsarist government treated the Oirats as it did the Cossacks. The provision of monetary payments and dry goods, however, did not stop the mutual raiding, and, in some instances, both sides failed to fulfill its promises (Halkovic, 1985:41-54).

Another significant incentive the Tsarist government provided to the Oirats was tariff-free access to the markets of Russian border towns, where the Oirats were permitted to barter their herds and the items they obtained from Asia and their Muslim neighbors in exchange for Russian goods. Trade also occurred with neighboring Turkic tribes under Russian control, such as the Tatars and the Bashkirs. Intermarriage became common with such tribes. This trading arrangement provided substantial benefits, monetary and otherwise, to the Oirat tayishis, noyons and zaisangs.

Fred Adelman described this era as the Frontier Period, lasting from the advent of the Torghut under Kho Orluk in 1630 to the end of the great khanate of Kho Orluk’s descendant, Ayuka Khan, in 1724, a phase accompanied by little discernible acculturative change (Adelman, 1960:14-15):

- There were few sustained interrelations between Kalmyks and Russians in the frontier period. Routine contacts consisted in the main of seasonal commodity exchanges of Kalmyk livestock and the products thereof for such nomad necessities as brick tea, grain, textiles and metal articles, at Astrakhan, Tsaritsyn and Saratov. This was the kind of exchange relationship between nomads and urban craftsmen and traders in which the Kalmyks traditionally engaged. Political contacts consisted of a series of treaty arrangements for the nominal allegiance of the Kalmyk Khans to Russia, and the cessation of mutual raiding by Kalmyks on the one hand and Cossacks and Bashkirs on the other. A few Kalmyk nobles became russified and nominally Christian who went to Moscow in hope of securing Russian help for their political ambitions on the Kalmyk steppe. Russian subsidies to Kalmyk nobles, however, became an effective means of political control only later. Yet gradually the Kalmyk princes came to require Russian support and to abide in Russian policy.

During the era of Ayuka Khan, the Kalmyk Khanate reached its peak of military and political power. The Khanate experienced economic prosperity from free trade with Russian border towns, China, Tibet and with their Muslim neighbors. During this era, Ayuka Khan also kept close contacts with his Oirat kinsmen in Dzungaria, as well as the Dalai Lama in Tibet.

List of invasions, wars and raids

- 1603. Kalmyks attacked the Khanate of Khiva (V.V.Bartold), and after a while some of the areas devastated Bukhara Khanate ("History of Uzbekistan").

- 1607 Kalmyks have a major military clash with the Kazakh Khanate.

- 1619: Kalmyks captured Nogais.

- 1620: The Kalmyks attack Bashkirs territory.

- 1635: Winter, went to war against Astrakhan Tatars.

- 1645 Kalmyks attacked Kabardia of North Caucasus.

- 1650: Kalmyks attacked Astarabad region (northeastern Iran), and sent messengers to the Shah of Persia.

- 1658: Successful campaign against Crimean Tatars, Nogais.

- 1660: In Tomsk, Kalmyks killing many men and capturing more than seven hundred women and children.

- 1661: June 11, Kalmyks went to war with the Crimean khan.

- 1666: At the request of the Russian government, troops of Kalmyks participated in the fighting on Ukraine against the Tatars, Turks and Polish.

- 1668: In the united forces of Kalmyks and Cossacks took part in the campaign against the Crimea.

- 1676: A part of the Kalmyks led Mazan Batyr in the Russian-Turkish war.

- 1676: Kalmyks in alliance with the Kabardians to stop the advance of the Turkish-Crimean troops to Kiev and Chuguev.

- 1678: Kalmyks, Don Cossacks repulsed, and then defeated the army of the Crimean Khan Murad Giray.

- 1680: Kalmyks raided Penza.

- 1684: Kalmyks city was captured by Sairam. Ayuka Khan made a successful campaign against the Kazakhs, Turkmens and Karakalpaks.

- 1696: Kalmyks participated in the capture of Azov.

- 1698: Kalmyks raids Crimean Tatars in the south of Russia and Ukraine.

- 1700: Kalmyks are actively involved in the Northern War, including the Battle of Poltava.

- 1711: 20,474 Kalmyks and 4,100 Russians attack Kuban. They kill 11,460 Nogais, drown 5,060 others and return with 2,000 camels, 39,200 horses, 190,000 cattle, 220,000 sheep and 22,100 human captives, of whom only 700 were adult males. On the way home they meet and defeat a returning Nogai war party and free 2,000 Russian captives.[3]

- 1735: Kalmyks are involved in the Russian-Turkish war.

- 1735: Kalmyks make successful campaigns in the Kuban and the Crimea.

- 1741: Kalmyks detachments took part in the Russian-Swedish war.

- 1756-1761: Kalmyks participated on Seven Years War

From Oirat to Kalmyk

Historically, the West Mongolian tribes identified themselves by their respective tribal names. Probably, in the 15th century, the four major West Mongolian tribes formed an alliance, adopting "Dörben Oirat" as their collective name. After the alliance dissolved, the West Mongolian tribes were simply called "Oirat." In the early 17th century, a second great Oirat State emerged, called the Dzungar Khanate. While the Dzungars (initially Choros, Dörbet and Khoit tribes) were establishing their empire in Western Inner Asia, the Khoshuts were establishing the Khoshut Khanate in Tibet, protecting the Gelugpa sect from its enemies, and the Torghuts formed the Kalmyk Khanate in the lower Volga region.

After encamping, the Oirats began to identify themselves as "Kalmyk." This named was supposedly given to them by their Muslim neighbors and later used by the Russians to describe them. The Oirats used this name in their dealings with outsiders, viz., their Russian and Muslim neighbors. But, they continued to refer to themselves by their tribal, clan, or other internal affiliations.

The name Kalmyk, however, wasn't immediately accepted by all of the Oirat tribes in the lower Volga region. As late as 1761, the Khoshut and Dzungars (refugees from the Qing Empire) referred to themselves and the Torghuts exclusively as Oirats. The Torghuts, by contrast, used the name Kalmyk for themselves as well as the Khoshut and Dzungars. (Khodarkovsky, 1992:8)

Generally, European scholars have identified all West Mongolians collectively as Kalmyks, regardless of their location (Ramstedt, 1935: v-vi). Such scholars (e.g. Sebastian Muenster) have relied on Muslim sources who traditionally used the word Kalmyk to describe the Oirats in a derogatory manner. But the Oirats of China and Mongolia have regarded that name as a term of abuse (Haslund, 1935:214-215). Instead, they use the name Oirat or the go by their respective tribal names, e.g., Khoshut, Dörbet, Choros, Torghut, Khoit, Bayid, Mingat, etc. (Anuchin, 1914:57).

Over time, the descendants of the Oirat migrants in the lower Volga region embraced the name Kalmyk, irrespective of their locations, viz., Astrakhan, the Don Cossack region, Orenburg, Stavropol, the Terek and the Urals. Another generally accepted name is Ulan Zalata or the "red buttoned ones" (Adelman, 1960:6).

Reduction in autonomy, 1724-1771

After the death of Ayuka Khan in 1724, the political situation among the Kalmyks became unstable as various factions sought to be recognized as Khan. The Tsarist government also gradually chipped away at the autonomy of the Kalmyk Khanate. These policies, for instance, encouraged the establishment of Russian and German settlements on pastures the Kalmyks used to roam and feed their livestock. In addition, the Tsarist government imposed a council on the Kalmyk Khan, thereby diluting his authority, while continuing to expect the Kalmyk Khan to provide cavalry units to fight on behalf of Russia. The Russian Orthodox church, by contrast, pressured many Kalmyks to adopt Orthodoxy. By the mid-17th century, Kalmyks were increasingly disillusioned with settler encroachment and interference in its internal affairs.

In the winter of 1770-1771, Ubashi Khan, the great-grandson Ayuka Khan and the last Kalmyk Khan, decided to return his people to their ancestral homeland, Dzungaria, then under control of the Qing dynasty.[4] The Dalai Lama was contacted to request his blessing and to set the date of departure. After consulting the astrological chart, the Dalai Lama set the return date, but at the moment of departure, the weakening of the ice on the Volga River permitted only those Kalmyks who roamed on the left or eastern bank to leave. Those on the right bank were forced to stay behind.

Under Ubashi Khan’s leadership, approximately 200,000 Kalmyks began the journey from their pastures on the left bank of the Volga River to Dzungaria. Approximately five-sixths of the Torghut tribe followed Ubashi Khan. Most of the Khoshuts, Choros and Khoits also accompanied the Torghuts on their journey to Dzungaria. The Dörbet tribe, by contrast, elected not to go at all. The Kalmyks who resettled in Qing territory became known as Torghuts. While the first phase of their movement became the Old Torghuts, the Qing called the later Torghut immigrants "New Torghut". The size of the departing group has been variously estimated between 150,000 and 400,000 people, with perhaps as many as six million animals (cattle, sheep, horses, camels and dogs).[5] Beset by raids, thirst and starvation, approximately 66,000 survivors made it to Dzungaria.

After failing to stop the flight, Catherine the Great abolished the Kalmyk Khanate, transferring all governmental powers to the Governor of Astrakhan. The title of Khan was abolished. The highest native governing office remaining was the Vice-Khan who also was recognized by the government as the highest ranking Kalmyk prince. By appointing the Vice-Khan, the Tsarist government was now permanently the decisive force in Kalmyk government and affairs.

List of Kalmyk Khans

- Kho Orluk (1633-1644)

- Shukhur Daichin (1644-1661)

- Puntsug (Monchak) (1661-1672)

- Ayuka Khan (1672-1723)

- Tseren Donduk Khan (1723-1735)

- Donduk Ombo Khan (1735-1741)

- Donduk Dashi Khan (1741-1761)

- Ubashi Khan (1761-1771)

- Dodbi Khan (1771-1781)

- As Saray Khan (1781)

See also

References

- Dunnell, Ruth W.; Elliott, Mark C.; Foret, Philippe; Millward, James A (2004). New Qing Imperial History: The Making of Inner Asian Empire at Qing Chengde. Routledge. ISBN 1134362226. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Millward, James A. (1998). Beyond the Pass: Economy, Ethnicity, and Empire in Qing Central Asia, 1759-1864 (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804729336. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Perdue, Peter C (2009). China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia (reprint ed.). Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674042026. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

Notes

- ↑ Forsyth, James. A History of the Peoples of Siberia: Russia's North Asian Colony 1581-1990.

- ↑ "Republic of Kalmykia". Kommersant. 2004-03-10. Retrieved 2007-04-06. "The Kalmyk Khanate reached its peak of power in the period of Ayuka Khan (1669 -1724). Protected the southern borders of Russia and conducted many military expeditions against the Crimean Tatars, Ottoman Empire and Kuban Tatars. He also waged wars against the Kazakhs, subjugated the Mangyshlak Turkmens, and made multiple expeditions against the highlanders of the North Caucasus."

- ↑ Khodarkovsky, Where Two Worlds Meet, p149

- ↑ Perdue 2009, p. 295.

- ↑ DeFrancis, John. In the Footsteps of Genghis Khan. University of Hawaii Press, 1993.