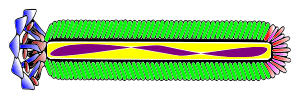

M13 bacteriophage

| M13 bacteriophage | |

|---|---|

| |

| Blue: Coat Protein pIII; Brown: Coat Proteín pVI; Red: Coat Protein pVII; Limegreen: Coat Protein pVIII; Fuchsia: Coat Proteín pIX; Purple: Single Stranded DNA | |

| Virus classification | |

| Group: | Group II (ssDNA) |

| Family: | Inoviridae |

| Genus: | Inovirus |

| Species | |

M13 is a virus that infects the bacterium Escherichia coli. It is composed of a circular single-stranded DNA molecule encased in a thin flexible tube made up of about 2700 copies of a single protein called P8, the major coat protein. The ends of the tube are capped with minor coat proteins. Infection starts when the minor coat protein P3 attaches to the receptor at the tip of the F pilus of the bacterium. Infection with M13 is not lethal; however, the infection causes turbid plaques in E. coli because infected bacteria grow more slowly than the surrounding uninfected bacteria. It engages in a viral lifestyle known as a chronic infection which is neither lytic or temperate. However a decrease in the rate of cell growth is seen in the infected cells. M13 plasmids are used for many recombinant DNA processes, and the virus has also been studied for its uses in nanostructures and nanotechnology.

Phage particles

The phage coat is primarily assembled from a 50 amino acid protein called pVIII (or p8), which is encoded by gene VIII (or g8) in the phage genome. For a wild type M13 particle, it takes approximately 2700 copies of p8 to make the coat about 900 nm long. The coat's dimensions are flexible though and the number of p8 copies adjusts to accommodate the size of the single stranded genome it packages. For example, when the phage genome was mutated to reduce its number of DNA bases (from 6.4 knt to 221 nt),[1] then the number of p8 copies was decreased to fewer than 100, causing the p8 coat to shrink in order to fit the reduced genome. The phage appear to be limited at approximately twice the natural DNA content. However, deletion of a phage protein (p3) prevents full escape from the host E. coli, and phage that are 10-20X the normal length with several copies of the phage genome can be seen shedding from the E. coli host.

There are four other proteins on the phage surface, two of which have been extensively studied. At one end of the filament are five copies of the surface exposed pIX (p9) and a more buried companion protein, pVII (p7). If p8 forms the shaft of the phage, p9 and p7 form the "blunt" end that is seen in the micrographs. These proteins are very small, containing only 33 and 32 amino acids respectively, though some additional residues can be added to the N-terminal portion of each which are then presented on the outside of the coat. At the other end of the phage particle are five copies of the surface exposed pIII (p3) and its less exposed accessory protein, pVI (p6). These form the rounded tip of the phage and are the first proteins to interact with the E. coli host during infection. p3 is also the last point of contact with the host as new phage bud from the bacterial surface.

Replication in E. coli

Below are steps involved with replication of M13 in E. coli.

- Viral (+) strand DNA enters cytoplasm

- Complementary (-) strand is synthesized by bacterial enzymes

- DNA Gyrase, a type II topoisomerase, acts on double-stranded DNA and catalyzes formation of negative supercoils in double-stranded DNA

- Final product is parental replicative form (RF) DNA

- A phage protein, pII, nicks the (+) strand in the RF

- 3'-hydroxyl acts as a primer in the creation of new viral strand

- pII circulizes displaced viral (+) strand DNA

- Pool of progeny double-stranded RF molecules produced

- Negative strand of RF is template of transcription

- mRNAs are translated into the phage proteins

Phage proteins in the cytoplasm are pII, pX, and pV, and they are part of the replication process of DNA. The other phage proteins are synthesized and inserted into the cytoplasmic or outer membranes.

- pV dimers bind newly synthesized single-stranded DNA and prevent conversion to RF DNA

- RF DNA synthesis continues and amount of pV reaches critical concentration

- DNA replication switches to synthesis of single-stranded (+) viral DNA

- pV-DNA structures from about 800 nm long and 8 nm in diameter

- pV-DNA complex is substrate in phage assembly reaction

Applications

George Smith, among others, showed that fragments of EcoRI endonuclease could be fused in the unique Bam site of f1 filamentous phage and thereby expressed in gene III whose protein pIII was externally accessible. M13 does not have this unique Bam site in gene III. M13 had to be engineered to have accessible insertion sites, making it limited in its flexibility in handling different sized inserts. Because the M13 phage display system allows great flexibility in the location and number of recombinant proteins on the phage, it is a popular tool to construct or serve as a scaffold for nanostructures.[2] For example, the phage can be engineered to have a different protein on each end and along its length. This can be used to assemble structures like gold or cobalt oxide nano-wires for batteries[3] or to pack carbon nanotubes into straight bundles for use in photovoltaics.[4]

See also

References

- ↑ Specthrie, L; Bullitt, E; Horiuchi, K; Model, P; Russel, M; Makowski, L (1992). "Construction of a microphage variant of filamentous bacteriophage.". Journal of Molecular Biology. 228 (3): 720–4. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(92)90858-h. PMID 1469710.

- ↑ Huang, Yu; Chung-Yi Chiang, Soo Kwan Lee, Yan Gao, Evelyn L. Hu, James De Yoreo, Angela M. Belcher (2005). "Programmable Assembly of Nanoarchitectures Using Genetically Engineered Viruses". Nano Lett. 5 (7): 1429–1434. doi:10.1021/nl050795d. ISSN 1530-6984. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - ↑ Nam, Ki Tae; Dong-Wan Kim; Pil J Yoo; Chung-Yi Chiang; Nonglak Meethong; Paula T Hammond; Yet-Ming Chiang; Angela M Belcher (2006-05-12). "Virus-Enabled Synthesis and Assembly of Nanowires for Lithium Ion Battery Electrodes". Science. 312 (5775): 885–888. doi:10.1126/science.1122716. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 16601154. Retrieved 2012-03-23.

- ↑ Dang, Xiangnan; Hyunjung Yi, Moon-Ho Ham, Jifa Qi, Dong Soo Yun, Rebecca Ladewski, Michael S. Strano, Paula T. Hammond, Angela M. Belcher (2011-04-24). "Virus-templated self-assembled single-walled carbon nanotubes for highly efficient electron collection in photovoltaic devices". Nature Nanotechnology. 6 (6): 377–384. doi:10.1038/nnano.2011.50. ISSN 1748-3387. Retrieved 2012-03-23. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help)

External links

- 20.109(S07): Start-up Genome Engineering

- Phage Display: A Laboratory Manual

- Messing, J (1993), "M13 cloning vehicles. Their contribution to DNA sequencing.", Methods Mol. Biol., 23, pp. 9–22, doi:10.1385/0-89603-248-5:9, ISBN 0-89603-248-5, PMID 8220775

|chapter=ignored (help) Included in DNA Sequencing Protocols by Griffin, Annette M.; Griffin , Hugh G. (large 21mb file) - "Universal plaque-busting drug could treat various brain diseases". Retrieved 2015-08-12.