Marko Miljanov

| Marko Miljanov | |

|---|---|

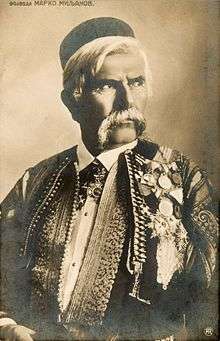

Miljanov at old age, seen in folk costume, with numerous medals | |

| Born |

25 April 1833 Medun, Ottoman Empire (present-day Montenegro) |

| Died |

2 February 1901 (aged 67) Herceg Novi, Principality of Montenegro (present-day Montenegro) |

| Cause of death | Natural |

| Nationality | Montenegrin |

| Education | None |

| Occupation | Clan chief, statesman, writer |

| Known for | Literary works on Montenegrin society. |

| Title |

Chief of the Kuči clan Chief of the Bratonožići clan |

| Denomination | Serbian Orthodox Christian |

Marko Miljanov Popović (Serbian Cyrillic: Марко Миљанов Поповић, pronounced [mâːrkɔ mǐʎanɔʋ pɔ̌pɔʋit͡ɕ]; 25 April 1833 – 2 February 1901) was a Brda chieftain and Montenegrin general and writer. He entered the service of Danilo I, the first secular Prince of Montenegro in the modern era, and led his armed Kuči tribe against the Ottoman Empire in the wars of 1861–62 and 1876–78, distinguishing himself as an able military leader. He managed to unite his tribe with Montenegro in 1874. There was later a rift between Miljanov and Prince Nikola I. He was also an accomplished writer who gained repute for his descriptions of Montenegrin society. His grand-daughter Olgivanna Lloyd Wright headed Frank Lloyd Wright's iconic fellowship and foundation in the United States.

Biography

Marko was born in the village of Medun on 25 April (St. Mark's Day) 1833, and was given the name "Marko" accordingly. His father was Miljan Jankov Popović, his mother Borika, born in Oraovo.[1] He was baptized by Orthodox priest Spasoje Jokov Popović.[2]

The village of Medun was located in the Kuči tribe (in present-day Podgorica municipality, Montenegro) of the Brda (Highland) region. The tribe at the time was de facto independent from the Ottoman Empire as well as the direct rule of Petar II Petrović-Njegoš. The tribe was caught up in internal blood feuding since 1825, for the next 50 years, with brotherhoods (clans) plotting with the Pasha of Scutari or other tribes to deal with their enemies.[3] Like his fellow highlanders, Miljanov took part in hajdučija (guerilla fighting) against the Ottomans in the region.

In 1856, he came to the Montenegrin capital Cetinje and entered the service of Prince Danilo in his guards unit called perjanici. For his bravery and successes in raids on Ottoman territory and as a man of confidence, he was awarded in 1862 the position of judge and head of Bratonožići tribe (that neighboured Kuči). For his work on the unification of Kuči with Montenegro in 1874, he had a price set on his head by the Ottomans. The same year saw his appointment to the Montenegrin Senate (from 1879 transformed into a State Council). In the 1876–78 war against the Ottomans, he was one of three commanders that victoriously led Montenegrin forces in the Battle of Fundina. In 1879 the Brda forces under his supreme command were defeated by the Ottoman irregulars in the Battle of Novšiće, fought for the territory of Plav and Gusinje. After a fierce disagreement with Prince Nikola in 1882, he had to leave the State Council and decided to retire from public life to his native Medun.

Although he was 50 years old, Marko Miljanov, who was illiterate like the most of his countrymen, decided to learn to write. Though much younger than Petar II Petrović Njegoš, Marko Miljanov was closer to the people by virtue of his lack of learning, and thus he expressed more directly and in less altered form what he found among the people. He states explicitly that man is governed by higher powers of good and evil: This is not permitted by nature, this is not permitted by the blood which contains some divine force which rules over man's good will and bad. Putting quotations aside, Miljanov is lost in admiration for the good, for humanity and reason as the higher imperatives over man.

He explained his urge in a foreword to the lost manuscript of his epic songs with the words: Dear Serb brother, if you had the chance to see the heroes that I have seen, your heart would give you no peace until you have responded to the heroes who die merrily for their own and rights of all of us.

He died at Herceg Novi in 1901.

Works

Marko Miljanov died before any of his works were published. All works were originally published in Serbia, as Marko was a well-known dissident to King Nicholas.

- Examples of Humanity and Bravery (Serbian: Примјери чојства и јунаштва, Belgrade 1901), his most important work, is a collection of true anecdotes depicting practical examples of achieved ethical ideal Montenegrins of his time strived for. It is a lasting monument to the otherwise unsung heroes of the Montenegrin struggle for independence in the 19th century. The anecdotes describe common and humble people, their language and customs and their deeds that made other Montenegrins and Albanians admire them. Marko's language and phrase is plain and coarse, however, his message is resounding.

- The Kuči Tribe in Folk Stories and Poems (Serbian: Племе Кучи у народној причи и пјесми, Belgrade 1904), his second published book, is a collection of historical, folkloric and ethnographical (anthropological) data on the Kuči tribe.

- Life and the Customs of Albanians (Serbian: Живот и обичаји Арбанаса), is a work on the immediate neighboring Albanian Catholic tribes which describes their culture and daily life. Written in 1907 describing the customs of the Albanian malesoris (highlanders). Although he spent a life time fighting the Albanians, he was also much fascinated and an admirer. The book was published posthumously. The book describes the culture of Northern Albanian highlanders (the "Malissori"), their customs (including besa, "oath", and vendetta), kinship and hospitality.

- Serbian Hajduks (Serbian: Српски хајдуци), epic

- Something about the Bratonožići (Serbian: Нешто о Братоножићима), epic

Ethnicity

Miljanov considered himself a Serb. Near the end of his life, Miljanov wrote a letter to one of the Kuči clan leaders. In the letter he writes:

I am dying happy, and although I didn't live long enough to read my books, I'll be listening from the grave as grandsons of my friends read them. As a Kuč, I am dying mostly happy, but as a Serb, I'm dying unhappy and dissatisfied.— [4]

References

- ↑ Đukić 1957, p. 10.

- ↑ Miljanov 1904, p. vii.

- ↑ Mirović 2013, para. 1.

- ↑ Mirović 2013.

Bibliography

- Đukić, Trifun (1957). Marko Miljanov. Nolit.

- Jovanović, J. (1952). Marko Miljanov. Cetinje.

- Miljanov, Marko (1904). Племе Кучи у народној причи и пјесми.

- Mirović, Dejan (15 May 2013). "Marko Miljanov – srpski heroj i pisac". Nova srpska politička misao. Retrieved 26 May 2016.

- O., C. (29 January 1944). "Марко Миљанов". Српски народ: 7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Marko Miljanov. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Marko Miljanov |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |