Neoplatonism and Gnosticism

| Part of a series on | |||

| Gnosticism | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| History | |||

| Proto-Gnostics | |||

| Scriptures | |||

|

|||

| Lists | |||

| Related articles | |||

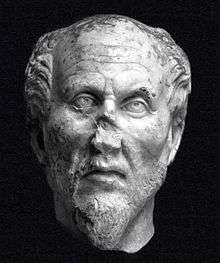

Neoplatonism (also Neo-Platonism) is the modern term for a school of Hellenistic philosophy that took shape in the 3rd century, based on the teachings of Plato and some of his early followers. Neoplatonism took definitive shape with the philosopher Plotinus, who claimed to have received his teachings from Ammonius Saccas, a dock worker and philosopher in Alexandria. Neoplatonists considered themselves simply "Platonists", although they also wished to distinguish themselves from various earlier interpreters of Plato, such as the New Academy followers of skepticism like Arcesilaus and Cicero, Clitomachus, Carneades with its probabilistic account of knowledge. A more precise term for the group, suggested by the scholar John D. Turner, is "orthodox Neoplatonism".[1]

Gnosticism is a term created by modern scholars to describe a collection of religious groups, many of which thought of themselves as Christians, and which were active in the first few centuries AD.[2] There has been considerable scholarly controversy over exactly which sects fall within this grouping. Sometimes Gnosticism is used narrowly to refer only to religious groups such as Sethians and Archontics who seem to have used the term gnostikoi as a self-designation, even though early Platonists and Ebionites also used the term and are not considered to be Gnostics. Sometimes it is used a little more broadly to include groups similar to or influenced by Sethians, such as followers of Basilides or Valentinius and later the Paulicians. Sometimes it is used even more broadly to cover all groups which heavily emphasized gnosis, therefore including Hermetics and Neoplatonists as well.

This article discusses the relationship between Neoplatonism and Gnosticism.

Platonic origins of the term "Gnostikoi"

Gnosis is a Greek word, originally used in specifically Platonic philosophical contexts. Plato's original use of the terms gnostikoi and gnostike episteme were in his text known as Politikos in Greek and Politicus in Latin (258e-267a). In this work, the modern name of which is the Statesman, gnosis meant the knowledge to influence and control. Gnostike episteme also was used to indicate one's aptitude. In Plato's writings the terms do not appear to intimate anything esoteric or hidden, but rather express a sort of higher intelligence and ability akin to talent.

Within the text of Politikos, the Stranger (the main speaker in the dialog) indicates that the best political leaders are those that have this certain "knowledge" indicative of a competency to rule. Gnosis therefore was a quality characteristic of the ideal attendee of the Platonic Academy, since high aptitude would be a necessary qualification to understand and grasp its teachings.

Although the Greek stem gno- was in common use, "like many of the new words formed with -(t)ikos, gnostikos was never very widely used and never entered ordinary Greek; it remained the more or less exclusive property of Plato's subsequent admirers, such as Aristotle, Philo Judaeus, Plutarch, Albinus, Iamblichus and Ioannes Philoponus. Most important of all in its normal philosophical usage gnostikos was never applied to the person as a whole, but only to mental endeavours, facilities, or components of personality."[3] Thus, if it really is true that some Christians referred to themselves as gnostikoi, or "professed to be" gnostikoi, as Porphyry and Celsus (two pagans who wrote against Christianity), Clement of Alexandria, and Irenaeus claim, then this would be the novel coinage of a very distinctive moniker as opposed to a continuation of traditional usage. Further, it might well mark a self-designating proper name rather than merely a self-description. Indeed, it would have sounded like technical philosophical jargon at the time. In contrast, merely claiming to have or supply gnosis would have been a common claim in the 2nd century CE, unworthy of notice in many Christian and Hellenistic circles.

Historical relations between Neoplatonism and Gnosticism

There are four major epochs in the history of Platonic thought: the "Old Academy," the "New Academy," Middle Platonism and Neoplatonism. After Plato's death in 348 BC, the leadership of his Academy was taken up by his nephew, Speusippus, and then by Xenocrates, Polemon, Crantor, and Crates of Athens, who had been leaders of the "Old Academy." Following Crates, in 268 BC was Arcesilaus of Pitane who founded the "New Academy," under the influence of Pyrrhonian scepticism. Arcelisaus modeled his philosophy after the Socrates of Plato's early dialogues, "suspending judgment" or "epoche" (epokhê peri pantôn ἐποχὴ περὶ πάντων).

Antiochus of Ascalon, who headed the Academy from 79-78 BC, sought to intellectually maneuver around the scepticism of the New Academy by way of a return to the dogmata of Plato and the Old Academy philosophers. Antiochus argued that the Platonic Forms (see Platonic realism) are not transcendent but immanent to rational minds (including that of God). This position, along with his treatment of the Platonic Demiurge (from the Theaetetus) and the World-Soul (a notion from the Timaeus that the physical world was an animated being), framed the work of other middle Platonists (such as Philo of Alexandria) and later Platonists such as Plutarch of Chaeronea, Numenius of Apamea, and Albinus. These treatments of the forms and of the Demiurge were crucially influential to both Neoplatonism and Gnosticism. Neopythagoreanism seems to have influenced both the Neoplatonists and the Gnostics as well.[4] Further, Neopythagoreanism and Middle Platonism seem to be important influences on Basilides and on the Hermetic tradition, which seem in turn to have influenced the Valentinians.[5] Indeed, the Nag Hammadi texts included excerpts from Plato, and Irenaeus claims that followers of Carpocrates honored images of Pythagoras, Plato, and Aristotle along with images of Jesus Christ.

Neoplatonism

By the third century Plotinus had shifted Platonist thought far enough that modern scholars consider the period a new movement called "Neoplatonism"—although Plotinus took his position to conform with the Old Academics and the Middle Platonists, especially via his teacher Ammonius Saccas; Alexander of Aphrodisias, who was later head of the Lyceum in Athens; and Numenius of Apamea a forerunner of the Neo-Pythagoreans and Neo-Platonists. Plotinus seems to have been influenced by Gnostics only to the extent of writing a polemic against them (which Porphyry has rearranged into Ennead 3.8, 5.8, 5.5, and 2.9).[6]

Gnosticism

Scholarship on Gnosticism has been greatly advanced by the discovery and translation of the Nag Hammadi texts, which shed light on some of the more puzzling comments by Plotinus and Porphyry regarding the Gnostics. More importantly, the texts help to distinguish different kinds of early Gnostics. It now seems clear that "Sethian" and "Valentinian"[7] gnostics attempted "an effort towards conciliation, even affiliation" with late antique philosophy,[8] and were rebuffed by some Neoplatonists, including Plotinus. Plotinus considered his opponents "heretics",[9] "imbeciles" and "blasphemers"[10] erroneously arriving at misotheism as the solution to the problem of evil, taking all their truths over from Plato.[11] They were in conflict with the idea expressed by Plotinus that the approach to the infinite force which is the One or Monad can not be through knowing or not knowing.[12][13] Although there has been dispute as to which gnostics Plotinus was referring to, it appears they were Sethian.[14]

The earliest origins of Gnosticism are still obscure and disputed, but they probably include influence from Plato, Middle Platonism and Neo-Pythagoreanism, and this seems to be true both of the more Sethian Gnostics, and of the Valentinian Gnostics.[4] Further, if we compare different Sethian texts to each other in an attempted chronology of the development of Sethianism during the first few centuries, it seems that later texts are continuing to interact with Platonism. Earlier texts such as Apocalypse of Adam show signs of being pre-Christian and focus on the Seth of the Jewish bible (not the Egyptian God Set who is sometimes called Seth in Greek). These early Sethians may be identical to or related to the Ophites or to the sectarian group called the Minuth by Philo. Later Sethian texts such as Zostrianos and Allogenes draw on the imagery of older Sethian texts, but utilize "a large fund of philosophical conceptuality derived from contemporary Platonism, (that is late middle Platonism) with no traces of Christian content.".[4] Indeed the Allogenes doctrine of the "triple-powered one" is "the same doctrine as found in the anonymous Parmenides commentary (Fragment XIV) ascribed by Hadot to Porphyry ... and is also found in Plotinus' Ennead 6.7, 17, 13-26." [4] However, by the 3rd century Neoplatonists, such as Plotinus, Porphyry and Amelius are all attacking the Sethians. It looks as if Sethianism began as a pre-Christian tradition, possibly a syncretic Hebrew[15] Mediterranean baptismal movement from the Jordan Valley. With Babylonian and Egyptian pagan elements, Hellenic philosophy. That incorporated elements of Christianity and Platonism as it grew, only to have both Christianity and Platonism reject and turn against it. John D. Turner believes that this double attack led to Sethianism fragmentation into numerous smaller groups (Audians, Borborites, Archontics and perhaps Phibionites, Stratiotici, and Secundians).

Philosophical relations between Neoplatonism and Gnosticism

Gnostics borrow a lot of ideas and terms from Platonism. They exhibit a keen understanding of Greek philosophical terms and the Greek Koine language in general, and use Greek philosophical concepts throughout their text, including such concepts as hypostasis (reality, existence), ousia (essence, substance, being), and demiurge (creator God). Good examples include texts such as the Hypostasis of the Archons[16] (Reality of the Rulers) or Trimorphic Protennoia (The first thought in three forms).

Gnostics structured their world of transcendent being by ontological distinctions whereby the plenitude of the divine world emerges from a sole high deity by emanation, radiation, unfolding and mental self-reflection. Likewise the technique of self-performable contemplative mystical ascent towards and beyond a realm of pure being is rooted in Plato's Symposium, and common in Gnostic thought, was also expressed by Plotinus (see Life of Plotinus). Divine triads, tetrads, and ogdoads in Gnostic thought often are closely related to Neo-Pythagorean arithmology. The trinity of the "triple-powered one" (with the powers consisting of the modalities of existence, life and mind) in Allogenes mirrors quite closely the Neoplatonic doctrine of the Intellect differentiating itself from the One in three phases called Existence or reality (hypostasis), Life, and Intellect (nous). Both traditions heavily emphasize the role of negative theology or apophasis, and Gnostic emphasis on the ineffability of God often echoes Platonic (and Neoplatonic) formulations of the ineffability of the One or the Good.

There were some important philosophical differences. Gnostics emphasized magic and ritual in a way that would have been disagreeable to the more sober Neoplatonists such as Plotinus and Porphyry, though perhaps not to later Neoplatonists such as Iamblichus. But Plotinus' main objection to the Gnostic teachings he encountered was to their rejection of the goodness of the demiurge and of the material world. He attacked the Gnostics for their vilification of Plato's ontology of the universe as contained in the Timaeus. Plotinus accused Gnosticism of vilifying the demiurge or craftsman that shaped the material world, and so ultimately for perceiving the material world as evil, or as a prison. Plotinus set forth that the demiurge is the nous (as an emanation of the One), which is the ordering principle or mind, also reason. Plotinus was critical of the gnostic derivation of the Demiurge from Wisdom as Sophia, the anthropomorphic personification of wisdom as a feminine spirit deity not unlike the goddess Athena or the Christian Holy Spirit. These objections seem applicable to some of the Nag Hammadi texts, although others such as the Valentinians, or the Tripartite Tractate, appear to insist on the goodness of the world and the Demiurge. (Plotinus indicated that if gnostics really believed this world to be a prison, then they might at any moment free themselves from it by committing suicide.)

First International Conference on Neoplatonism and Gnosticism

The First International Conference on Neoplatonism and Gnosticism at the University of Oklahoma in 1984 explored the relationship between Neoplatonism and Gnosticism. The conference also led to a book named Neoplatonism and Gnosticism.

The book's intent was to document the creation of a conference in the academic world exploring the relationship between late and middle Platonic philosophy and Gnosticism. The book marked a turning point in the discussion on the subject of Neoplatonism[17] because it took into account the understanding of the gnostics of Plotinus' day in light of the discovery of the Nag Hammadi library. Further discussions of the topics covered in the book led to the formation of a new committee of scholars to once again translate Plotinus' Enneads. Both Richard Wallis and A.H. Armstrong, the major editors of the work, have died since the completion of the book and conference.

This conference was held to cover some of the controversies surrounding these issues and other aspects of the two groups. The objective of the event (and the book that documents the event) was to clarify the relationship between Neoplatonism / Neoplatonists and the sectarian groups of the day, the Gnostics. The book republished the works of a wide spectrum of scholars in the field of philosophy. The book's content consisted of presentations that the experts delivered at the first International Conference. One purpose was to clarify the meaning of the words and phrases repeated in other religions and belief systems of the Mediterranean region during Plotinus' time. Another was to try to clarify the extent to which Plotinus' work followed directly from Plato, and how much influence Plotinus had on the religions of his time and vice versa. The conference and the book documenting it is considered a key avenue for dialogue among the different scholars in the history of philosophy.

Later conferences and studies

John D. Turner of the University of Nebraska has led additional conferences covering topics and materials relating to Neoplatonism and Gnosticism. Presentations from seminars that took place between 1993 and 1998 are published in the book Gnosticism and Later Platonism: Themes, Figures, and Texts Symposium Series (Society of Biblical Literature).[18]

Neoplatonism, Gnosticism and other movements

Neoplatonism and Gnosticism are probably also both influences on certain contemporary or later movements. A good example is Hermeticism. Hermeticism seems to have roots prior to the 3rd century, but also to have been influenced heavily by both Gnosticism and Neoplatonism.

- Druze.

- Hermeticism- Egyptian and Greek movements.

- Ismailism.

- Islam- sufism.

- Neoplatonism and Christianity: Irenaeus, Origen, Pseudo-Dionysius, Cappadocian Fathers, Basil the Great, Gregory of Nyssa, Gregory of Nazianzus

- Persian Gnosticism- Manicheanism and Mandaeism

See also

- Allegorical interpretations of Plato

- Henology

- History of Gnosticism

- Julian the Apostate

- Neoplatonism and Christianity

- Sophism

References

- ↑ Richard T. Wallis, Jay Bregman (eds.), Neoplatonism and Gnosticism, SUNY Press, 1992, p. 430 just talks about orthodox Neoplatonism

- ↑ Filoramo, Giovanni (1990). A History of Gnosticism. Blackwell. pp. 142-7

- ↑ Layton, Bentley. "Prolegomena to the Study of Ancient Gnosticism" in The Social World of the First Christians: Essays in Honor of Wayne Meeks. ed L. Michael White and O. Larry Yarborough. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1995

- 1 2 3 4 Turner, John. "Sethian Gnosticism: A Literary History" in Nag Hammadi, Gnosticism and Early Christianity, 1986 p. 59

- ↑ Layton, Bentley. The Gnostic Scriptures. Doubleday 1987

- ↑ Harder, Scrift Plotins.

- ↑ This is what the scholar A. H. Armstrong wrote as a footnote in his translation of Plotinus' Enneads in the tract named against the Gnostics. Footnote from Page 264 1. From this point to the end of ch.12 Plotinus is attacking a Gnostic myth known to us best at present in the form it took in the system of Valentinus. The Mother, Sophia-Achamoth, produced as a result of the complicated sequence of events which followed the fall of the higher Sophia, and her offspring the Demiurge, the inferier and ignorant maker of the material universe, are Valentinian figures: cp. Irenaeus, Adversus haereses 1.4 and 5. Valentinius had been in Rome, and there is nothing improbable in the presence of Valentinians there in the time of Plotinus. But the evidence in the Life ch.16 suggests that the Gnostics in Plotinus's circle belonged rather to the other group called Sethians on Archonties, related to the Ophites or Barbelognostics: they probably called themselves simply "Gnostics." Gnostic sects borrowed freely from each other, and it is likely that Valentinius took some of his ideas about Sophia from older Gnostic sources, and that his ideas in turn influenced other Gnostics. The probably Sethian Gnostic library discovered at Nag Hammadi included Valentinian treatise: ep. Puech, Le pp. 162-163 and 179-180.

- ↑ Schenke, Hans Martin. "The Phenomenon and Significance of Gnostic Sethianism" in The Rediscovery of Gnosticism. E. J. Brill 1978

- ↑ Introductory Note This treatise (No.33 in Porphyry's chronological order) is in fact the concluding section of a single long treatise which Porphyry, in order to carry out the design of grouping his master's works, more or less according to subject, into six sets of nine treatise, hacked roughly into four parts which he put into different Enneads, the other three being III. 8 (30) V. 8 (31) and V .5 (32). Porphyry says (Life ch. 16.11) that he gave the treatise the Title "Against the Gnostics" (he is presumably also responsible for the titles of the other sections of the cut-up treatise). There is an alternative title in Life. ch. 24 56-57 which runs "Against those who say that the maker of the universe is evil and the universe is evil. The treatise as it stands in the Enneads is a most powerful protest on behalf of Hellenic philosophy against the un-Hellenic heresy (as it was from the Platonist as well as the orthodox Christian point of view) of Gnosticism. A.H. Armstrong introduction to II 9. Against the Gnostics Pages 220-222

- ↑ They claimed to be a privileged caste of beings, in whom alone God was interested, and who were saved not by their own efforts but by some dramatic and arbitrary divine proceeding; and this, Plotinus claimed, led to immorality. Worst of all, they despised and hated the material universe and denied its goodness and the goodness of its maker . For a Platonist, is utter blasphemy -- and all the worse because it obviously derives to some extent from the sharply other-worldly side of Plato's own teaching (e.g. in the Phaedo). At this point in his attack Plotinus comes very close in some ways to the orthodox Christian opponents of Gnosticism, who also insist that this world is the work of God in his goodness. But, here as on the question of salvation, the doctrine which Plotinus is defending is as sharply opposed on other ways to orthodox Christianity as to Gnosticism: for he maintains not only the goodness of the material universe but also its eternity and its divinity. A.H. Armstrong introduction to II 9. Against the Gnostics Pages 220-222

- ↑ The teaching of the Gnostics seems to him untraditional, irrational and immoral. They despise and revile the ancient Platonic teachings and claim to have a new and superior wisdom of their own: but in fact anything that is true in their teaching comes from Plato, and all they have done themselves is to add senseless complications and pervert the true traditional doctrine into a melodramatic, superstitious fantasy designed to feed their own delusions of grandeur. They reject the only true way of salvation through wisdom and virtue, the slow patient study of truth and pursuit of perfection by men who respect the wisdom of the ancients and know their place in the universe. A.H. Armstrong introduction to II 9. Against the Gnostics Pages 220-222

- ↑ Faith and philosophy By David G. Leahy. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2013-08-17.

- ↑ Enneads VI 9.6

- ↑ A. H. Armstrong (translator), Plotinus' Enneads in the tract named Against the Gnostics: Footnote, p. 264 1. From this point to the end of ch.12 Plotinus is attacking a Gnostic myth known to us best at present in the form it took in the system of Valentinus. The Mother, Sophia-Achamoth, produced as a result of the complicated sequence of events which followed the fall of the higher Sophia, and her offspring the Demiurge, the inferior and ignorant maker of the material universe, are Valentinian figures: cp. Irenaues adv. Haer 1.4 and 5. Valentinius had been in Rome, and there is nothing improbable in the presence of Valentinians there in the time of Plotinus. But the evidence in the Life ch.16 suggests that the Gnostics in Plotinus's circle belonged rather to the other group called Sethians on Archonties, related to the Ophites or Barbelognostics: they probably called themselves simply "Gnostics." Gnostic sects borrowed freely from each other, and it is likely that Valentinius took some of his ideas about Sophia from older Gnostic sources, and that his ideas in turn influenced other Gnostics. The probably Sethian Gnostic library discovered at Nag Hammadi included Valentinian treatise: ep. Puech, Le pp. 162-163 and 179-180.

- ↑ http://www.amazon.com/dp/1565639448

- ↑ http://www.gnosis.org/naghamm/intpr.htm

- ↑ Wallis, Richard T. (1992). "Introduction". Neoplatonism and Gnosticism. New York Press. p. 2. ISBN 0-7914-1337-3.

Its study has, however been hindered until recently by lack of original Gnostics writings, the main exceptions being a few short texts quoted by the Church Fathers and some (mostly late) works translated from Greeks into Coptic, the native Egyptian language. Our picture has, however, been revolutionized by the discovery in late 1945 of a Coptic Gnostic library at Nag Hammadi in Upper Egypt

- ↑ http://ccat.sas.upenn.edu/rs/rak/courses/535/reviews/Turner-CP.htm

Bibliography

- Turner, John D., The Platonizing Sethian texts from Nag Hammadi in their Relation to Later Platonic Literature, ISBN 0-7914-1338-1.

- Turner, John D., and Ruth Majercik, eds. Gnosticism and Later Platonism: Themes, Figures, and Texts. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2000.

- Wallis, Richard T. (1992). Neoplatonism and Gnosticism for the International Society for Neoplatonic Studies, New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-1337-3 - ISBN 0-7914-1338-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Neoplatonism. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gnosticism. |

- International Society of Neoplatonic Studies

- Ancient philosophy society

- Society of Biblical Literature