Catholic Church in Bosnia and Herzegovina

| Part of a series on the |

| Catholic Church in Bosnia and Herzegovina |

|---|

|

|

People Pope Francis Current ordinaries Vinko Puljić · Franjo Komarica · Ratko Perić · Tomo Vukšić · Pero Sudar · Marko Semren Apostolic Nuncio Luigi Pezzuto Historical people Josip Stadler · Grgo Martić · Ivan Franjo Jukić |

|

Canonized people |

|

Churches and shrines |

|

Apparitions in Međugorje |

|

|

The Catholic Church in Bosnia and Herzegovina is part of the worldwide Catholic Church, under the spiritual leadership of the pope in Rome.

History

Antiquity

Metropolis of Sardica

Christianity arrived in Bosnia and Herzegovina during the 1st century. Saint Paul wrote in his Epistle to the Romans that he had brought the Gospel of Christ to Illyria. Saint Jerome, Doctor of the Church who was born in Stridon (today Šuica, Bosnia and Herzegovina), wrote that St. Paul preached in Illyria. It is therefore considered that Christianity arrived on the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina in the 1st century, through Paul's disciples or Paul himself. After the Edict of Milan, Christianity spread rapidly, and the Christians and bishops from the area of today's Bosnia and Herzegovina gathered around two metropolitan seats, Salona and Sirmium. Several early Christian dioceses developed in the 4th, 5th and 6th centuries. At the Church synod in Salona in 530 and 533, Andrija, Bishop of Bistue (episcopus Bestoensis), was mentioned. Bishop Andrija probably had the seat of in the Roman municipium Bistue Nova near Zenica. Synod in the Salona decided to create a new diocese, Diocese of Bistue Vetus, separating it from the Diocese of Bistue Nova. Several dioceses have developed on the south: Diocese of Martari (today Konjic), Diocese of Sarsenterum, Diocese of Delminium, Diocese of Baloie and Diocese of Lausinium.[1]

Medieval era

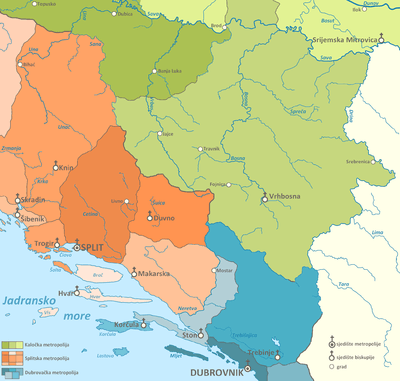

After the arrival of the Croats on the Adriatic coast in the early 7th century, Frankish and Byzantine rulers started baptizing Croats who inhabited the area of present-day Bosnia and Herzegovina to the Drina River. Christianization was also influenced by the proximity of the old Roman cities in Dalmatia. Christianity spread from the Dalmatian coast towards the interior of the Duchy of Croatia. This area was under the administration of archbishops of Split, successors of Salona's archbishops, who attempted to restore the ancient Duvno Diocese. Northern Bosnia was under the administration of the Pannonian-Moravian archbishopric established in 869 by Saint Methodius of Thessaloniki, Apostle to the Slavs.[2]

In 11th century Diocese of Bosnia was established. Based on a collection of historical documents Provinciale Vetus, published in 1188, which mention it twice, once subordinated to the Archdiocese of Split, and another time under the Archdiocese of Ragusa, it is assumed that it came into existence between 1060 and 1075.[3]

Ottoman era

During the 15th and 16th century the area of modern Bosnia and Herzegovina, which was then shared by the Kingdom of Croatia and Kingdom of Bosnia, fell under the Ottoman Islamic government. Christian subjects of the Ottoman Empire were given "protected persons" or "the people of the dhimma" status, which had guaranteed them the right to keep their possessions, work in agriculture, crafts and trade under the condition to be loyal subjects to the Ottoman government. In the public life Christians were not allowed to protest Islam, nor they were allowed to make any new churches or establish new Church institutions. Public and civil services were only performed by Muslims.[4]

The general attitude of the Islamic government toward Christians was further defined by other provisions for the Christian communities within the Ottoman state. Political reasons influenced that the Eastern Orthodox Church enjoyed a better position within the Empire. Since the pope, head of the Catholic Church, was also a political opponent of the Empire, Catholics were in the subordinated position in relation to the Orthodox. Unlike the Orthodox metropolitans and bishops, Catholic bishops were not recognized as high ecclesiastical dignitaries. Therefore, the Ottoman government officially recognized only certain Catholic communities, especially those in larger cities with a strong Catholic commercial citizenry. The authorities have issued them ahidnâmes, documents which guaranteed them right of identity, freedom of movement for priests, performing religious rituals, the inviolability of property, and the exemption of taxes of those members who have lived on charity. Mehmed the Conqueror issued two such documents to the Bosnian Franciscans. The first was issued after the conquest of Srebrenica in 1462, and the other during the main military campaign in the Kingdom of Bosnia in 1463. It was released in the Ottoman military camp in Milodraž situated on an important road connecting the towns of Visoko and Fojnica and hence is called Ahdname of Milodraž or Ahdname of Fojnica. However, the terms of this guarantee were often not implemented and Orthodox clergy often wanted to move part of their tax obligations to Catholics wherefore the Orthodox clergy and Franciscans often argued in front of the Ottoman courts.[4]

There are no direct and reliable sources on the number of Catholics during the Ottoman rule. Based on travelogues it is concluded that in the first half of the 16th century Catholic population still constitutes the majority. With them also were cited the Serbs who came from the east, the Turks who are mostly soldiers and officers and Islamicized part of the population. Apostolic Visitor Peter Masarechi in 1624 reported that Catholics make up about a quarter of the population while Muslims are the majority. During this century, Catholics will take third place in number of the population of Bosnia and Herzegovina and will keep it up to date.[4]

Restoration of regular ecclesiastical hierarchy

After Bosnia Vilayet came under Austro-Hungarian rule in 1878, pope Leo XIII has decided to restore regular ecclesiastical hierarchy in it. In the Apostolic Letter Ex hac augusta from 5 July 1881, Pope established a separate ecclesiastical province, consisting of 4 dioceses, in the political borders of Bosnia and Herzegovina and repealing previous apostolic vicariates. The city of Sarajevo, which is named the ancient name of Vrhbosna, became the archdiocesan and metropolitan seat. Its suffragan dioceses became the newly established dioceses in Banja Luka and Mostar and existing Trebinje-Mrkan Diocese. Since it is within the boundaries of the Mostar Diocese, Duvno (Delminium), ancient diocese, was located, the bishop of Mostar received the title of the bishop of Mostar-Duvno to maintain the memory of that diocese.[6]

In Vrhbosna, Cathedral chapter was immediately established while in other dioceses additional time was given for its establishment.[7]

Josip Juraj Strossmayer, bishop of Bosnia or Ðakovo and Srijem in his letter to Serafino Vannutelli, nuncio to Vienna, from March 1881, considered that the establishment of new dioceses is required but he was not for the establishment of metropolitan seat in Bosnia because it does not achieve the necessary bonding and connecting the Church in Croatia.[2]

Austro-Hungarian rule

In negotiations between the Holy See and Austro-Hungary, the Emperor of Austria had the decisive word in the appointment of bishops. Diocesan clergy had now been introduced along with Franciscans who during the Ottoman era were almost the only clergy in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Josip Stadler, professor of theology at University of Zagreb, was appointed as Archbishop of Vrhbosna while the dioceses of Mostar and Banja Luka were entrusted to the Franciscans Paškal Buconjić and Marijan Marković. Archbishop Stadler and diocesan priests attempted to suppress the Franciscans from parishes so the Archbishop requested from the Holy See permanent removal of the Franciscans from all parishes. Following the decision of the Holy See from 1883, Franciscans had to submit the part of their parish to the Archbishop at the free disposal. By the end of the century they handed over about a third of their parishes to local bishops. The Archbishop still sought to take as many parishes, which created frequent tension within the local Church.[4]

The number of Catholics during the Austro-Hungarian administration has increased by approximately 230,000. First of all it was the immigration from different parts of the Monarchy. The overall number of immigrants was about 135,000, of which 95,000 were the Catholics. Nationality of a third of immigrant Catholics was Croatian, while 60,000 of them were Czechs, Slovaks, Poles, Hungarians, Germans and Slovenians.[4]

Interwar period

Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (from 1929 Kingdom of Yugoslavia) was formed on 1 December 1918 by the merger of the provisional State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs (itself formed from territories of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire) with the formerly independent Kingdom of Serbia.

Although the opinions of Catholic Church circles in Bosnia and Herzegovina about the union with Serbia was divided, after the unification Catholic bishops, including Stadler, encouraged both priests and faithful on loyalty towards the new government. They considered that in the new State Croats can realize their national rights and that the Catholic Church will have rights and freedom of action. But eventually when it became obvious that things would not be such, relations between Church and State became colder and the clergy offered more resistance to the Government.[8]

Seven days after unification archbishop Stadler died. Ivan Šarić was supposed to be appointed his successor immediately after his death but the Royal government in Belgrade and the Franciscans in Bosnia were against him because they considered him Stadlers continuator. After three years, on 2 May 1922 Šarić was appointed Archbishop of Vrhbosna.[8]

During the communist Yugoslavia

The ideological conflict between Christianity and Marxist philosophy in Bosnia and Herzegovina during the Second World War and the era of the communist Yugoslavia became organized confrontation between the communist movement and the State and the Catholic Church. Under the direction of the Yugoslav Communist Party 184 churchmens were killed during and after the War. 136 of them were priests, 39 seminarians and four religious brothers, while five priests died in communist prisons. In these events, the most affected were the Franciscan provinces of Herzegovina and Bosna Srebrena whose 121 friars were killed. [9]

One of the largest calamities for the Catholic priests occurred during partisan conquest of Mostar and Široki Brijeg in February 1945. On that occasion the Partisans killed 30 friars from the convent in Široki Brijeg among them 12 professors and principal of Franciscan grammar school.[10]

The persecution of priests, the faithful and the Church was particularly organized after the War. Many books were printed and their goal was to link the Catholic Church with the fascist Ustaše regime, and the Western powers. In this way the Communist Party has sought to justify the crimes and persecution of the Church. Therefore the Party ignored the fact that 75 Catholic priests collaborated with the partisans and was a direct participant in their resistance movement.[11]

Faced with terror and open hostility of the Yugoslav communist authorities after completion of the Second World War, the Catholic bishops from the session in Zagreb sent out Pastoral Letter of the Catholic bishops of Yugoslavia on 20 September 1945 protesting against injustice, crime, trials to death and executions of people. They protected the sentenced innocent priests and faithful, noting that they do not want to defend the culprits. They admitted that the culprits do exist but that their number is negligible:

"We accept that there were some priests, who - seduced by the national party passion - violated the sacred law of Christian justice and love, and who therefore deserve to be tried in the court of terrestrial justice. We must however point out that the number of such priest is more than negligible, and that the serious allegations which have been presented in the press and in the meetings against a large part of the Catholic clergy in Yugoslavia, have to be included within tendentious attempts to deceive the public aware of the lies, and take away the reputation of the Catholic Church ..."

—Pastoral Letter [9]

The earthquake that struck the Banja Luka area in October 1969 significantly damaged Banja Luka Cathedral which therefore had to be demolished. During 1972 and 1973 on its site the present modern tent-shaped cathedral was built.[12]

In the Bosnian War

In August 1991, when the war in Croatia had already started, and in Bosnia and Herzegovina its beginning could surmise, archbishop Puljić and bishops Komarica and Žanić sent an appeal to the authorities, religious communities and the international community to preserve Bosnia and Herzegovina as a state and to prevent war. Yet among bishops there were different considerations how the internal organization of Bosnia and Herzegovina should look like. Žanić believed that every nation should have its separate unit within the country hoping that in this way they will secure a compact and homogeneous territory that would preserve constitutive rights of Croats in Bosnia and Herzegovina while archbishop Puljić and the leadership of the Franciscan Province of Bosnia Srebrena insisted on a single state without such divisions. In 1994, bishops demanded that the rights of all peoples have to be ensured in all areas of the country. So they opposed dividing Bosnia and Herzegovina on the several states because thus Catholic religious, sacral and cultural objects will remain largely outside the area that would be granted to Croats. They were also afraid that in this way the established borders of dioceses would be destroyed, which would consequently lead to the dissection of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Different political circumstances in Bosnia and Herzegovina resulted with different political standpoints that these ecclesiastical representatives started to support, especially regarding the ultimate position of Croats in the future organization of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[13]

Following the 1992-95 war, some fled to Croatia, and the local Bishop was said to be struggling to have them return to their homeland because of persistent difficulties there.[14]

Modern history

Pope John Paul II's visit to Banja Luka and Bosnia-Herzegovina of 23 June 2003 helped to draw the attention of Catholics worldwide to the need to reconstruct the Church in the country.[15] The destruction of churches and chapels was one of the most visible wounds of the 1992-95 war. In the Diocese of Banja Luka alone, which the Pope visited Sunday, 39 churches were destroyed and 22 suffered considerable damage. Nine chapels were destroyed and 14 were damaged; two convents were devastated and one severely damaged, as were 33 cemeteries.[15]

In 2009, the remains of friar Maksimilijan Jurčić, killed by Partisans on 28 January 1945, were discovered and subsequently buried in Široki Brijeg.[16][17] Among those in attendance at the funeral was Ljubo Jurčić the friar's nephew, and the Croatian consul-general in Mostar Velimir Pleša.[18] The cause of the martyrdom of the Herzegovinian Franciscans is led by the Vicepostulation Fra Leo Petrović and 65 Comrades.[19]

Hierarchy

The Church in Bosnia and Herzegovina has one province: Sarajevo. There are one archdiocese and 3 dioceses which are divided into archdeaconries, deaneries and parishes.

| Province | Diocese | Approximate Territory | Cathedral | Creation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sarajevo | ||||

| Archdiocese of Vrhbosna Archidioecesis Vrhbosnensis o Seraiensis | Central Bosnia, Semberija, Posavina, Podrinje | Sacred Heart Cathedral | 11th century (originally as Diocese of Bosnia, elevated to Archdiocese 1881) | |

| Diocese of Banja Luka Dioecesis Banialucensis | Bosanska Krajina, Tropolje, Donji Krajevi, Pounje | Cathedral of Saint Bonaventure | 5 July 1881 | |

| Diocese of Mostar-Duvno Dioecesis Mandentriensis-Dulminiensis | Herzegovina, Gornje Podrinje | Cathedral of Mary, Mother of the Church | 6th century (originally as Diocese of Duvno) | |

| Diocese of Trebinje-Mrkan Dioecesis Tribuniensis-Marcanensis | South and East Herzegovina | Cathedral of the Birth of Mary | 984 | |

| - | Military Ordinariate of Bosnia and Herzegovina Ordinariatus Militaris in Bosnia et Herzegovina | Bosnia and Herzegovina | 1 February 2011 |

Zavalje parish of the Diocese of Gospić-Senj is on the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

There are two Franciscan provinces in the country, the Franciscan Province of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary based in Mostar and the Franciscan Province of Bosna Srebrena based in Sarajevo.

Shrines in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Shrine of the Queen of Peace in Međugorje

_Medjugorje_-_Hotel_Pansion_Porta_-_Bosnia_Herzegovina_-_Creative_Commons_by_gnuckx_(4694635177).jpg)

Međugorje, a village located in Herzegovina and parish in Diocese of Mostar-Duvno, has been the site of alleged apparitions of the Virgin Mary since June 24, 1981. From the beginning it became an important place of pilgrimage for millions of people and thousands prayer groups. The phenomenon is not officially approved by the Catholic Church.[20][21] The Holy See announced in March 2010 that it had established a Commission under the auspices of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith to evaluate the apparitions, headed by Cardinal Camillo Ruini.[22]

Shrine of Our Lady of Olovo

Church of the Assumption is a Catholic church in Olovo known better as a Marian pilgrimage site. The Olovo Shrine of Our Lady is among the most important pilgrimage sites in Southeast Europe. According to one record back to 1679, to the Our Lady in Olovo pilgrimage were made by Catholics and gentiles, apart from Bosnia, also from Bulgaria, Serbia, Albania and Croatia. And nowadays the shrine in Olovo is an attractive place of pilgrimage. Pilgrimage mainly happens on the Feast of the Assumption, in the middle of August, but also in other circumstances. In the Olovo shrine are two paintings of Our Lady. One is from the 18th century labelled S. Maria Plumbensis, which until 1920 was with the Franciscans in Ilok, and later in Petrićevac and in Sarajevo, and in 1964 it was transferred to Olovo. The second painting was done in 1954 by Gabriel Jurkić by the description of the former Olovo Lady painting, which disappeared.

Shrine of Saint John the Baptist of Podmilačje

The Shrine of St. John the Baptist in Podmilačje is one of the oldest shrines in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Church of St. John is in the village of Podmilačje which is 10 kilometers away from Jajce, under massive stones on which there was, as presumed, a medieval tower from which the soldiers of Hrvoje Vukčić guarded and defended the entrance to the city. The first mention of Podmilačje is in a document of King Stjepan Tomašević dating from 1461. At that time, the church of St. John had already existed. On the basis of the stylistic features of the portal, it can be concluded that the construction of the church dates back to the mid-fifteenth century. During the Ottoman period the church was not damaged or destroyed. This is the only medieval church in Bosnia that continually served its purpose. According to legend, the church of St. John “moved” during the night from the village of Pšenik, on the left bank of the river Vrbas, to the village of Podmilačje, on the right bank of the river, because the Turks had been keeping goats in it. Legend also has it that one pillar still stands in the river Vrbas and can be seen when the water level is low. The area of the church of St. John in Podmilačje represents an important place of pilgrimage for Catholics. Once a year, on the eve of St. John’s feast which is on June 24, a multitude of people come to this place. The pilgrims believe in the healing properties of Saint John, especially for chronic and mental diseases.

Shrine of Saint Leopold Mandić in Maglaj

Maglaj is a town in central Bosnia located in the Bosna river valley near Doboj. The town was first mentioned on the 16 September 1408 in the Charter (sub castro nostro Maglay) of the Hungarian King Sigismund. The Parish Maglaj was officially restored in 1970, and in the same year a rectory was built. In autumn of 1976 an already dilapidated old church of St. Anthony was demolished built in 1919. Building of a new church and shrine of St. Leopold Mandić began in the spring of 1977 and its bases were blessed on the 15 May the same year. On the 17 June 1979, the shrine of St. Leopold Bogdan Mandić in Maglaj was ceremoniously opened.

Apostolic Nunciature

The Apostolic Nunciature to Bosnia and Herzegovina is an ecclesiastical office of the Roman Catholic Church in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The office of the nunciature has been located in Sarajevo since 1993. The first Apostolic Auncio to Bosnia and Herzegovina was Francesco Monterisi who was in office from June 1993 until March 1998. The current Apostolic Nuncio is His Most Reverend Excellency Luigi Pezzuto, who was appointed by Pope Benedict XVI on 17 November 2012.[23]

See also

References

- ↑ Catholic Encyclopedia:Bosnia and Herzegovina

- 1 2 Šanjek, Franjo (1996). Kršćanstvo na hrvatskom prostoru [Christianity in the Croatian regions] (in Croatian). Zagreb: Kršaćnska sadašnjost.

- ↑ OŠJ 1975, p. 134.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Vasilj, Snježana; Džaja, Srećko; Karamatić, Marko; Vukšić, Tomo (1997). Katoličanstvo u Bosni i Hercegovini [Catholicism in Bosnia and Herzegovina] (in Croatian). Sarajevo: HKD Napredak.

- ↑ "Stara crkva". zupavares.com. Vareš Parish. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- ↑ Leo XIII, Ex hac augusta

- ↑ Leo XIII, Ex hac augusta

- 1 2 Goluža, Božo (1995). Katolička Crkva u Bosni i Hercegovini 1918.-1941. Mostar: Teološki institut Mostar.

- 1 2 Lučić, Ivan (20 November 2011). "Progon Katoličke Crkve u Bosni i Hercegovini u vrijeme komunističke vlasti (1945–1990)". Croatica Christiana Periodica. 36: 105–144. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ↑ Pandžić, Bazilije (2001). Hercegovački franjevci sedam stoljeća s narodom [Herzegovinian franciscans seven centuries with people] (in Croatian). Mostar-Zagreb: Ziral.

- ↑ Petešić, Ćiril (1982). Katoličko svećenstvo u NOB-u 1941–1945 [Catholic clergy in National liberation movement] (in Croatian). Zagreb: VPA.

- ↑ "Župa Banja Luka". biskupija-banjaluka.org. Diocese of Banja Luka. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ↑ Krišto, Jure (June 2015). "Katolička Crkva u Bosni i Hercegovini (1991–1995)". Croatica Christiana Periodica. 39: 197–227. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ↑ ZENIT

- 1 2 Pope's Trip Helped Highlight the Plight

- ↑ Široki Brijeg: Pokopani posmrtni ostaci fra Maksimilijana Jurčića

- ↑ Misa za 66 ubijenih hercegovačkih franjevaca, Catholic Press Agency Zagreb

- ↑ FRA MAKSIMILIJAN POKOPAN CRKVI UZNESENJA BL. DJEVICE MARIJE

- ↑ Vicepostulatura postupka mučeništva »Fra Leo Petrović i 65 subraće«

- ↑ "Vatican Probes Claims of Apparitions at Medugorje". Reuters. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- ↑ Pope finally launches crackdown on world's largest illicit Catholic shrine and suspends 'dubious' priest. (Sep 3, 2008). Caldwell, Simon. Mail Online. Retrieved Feb 28, 2010.

- ↑ "Holy See confirms creation of Medjugorje Commission". Catholic News Agency (ACI Prensa). March 17, 2010.

- ↑ "Apostolic Nunciature Bosnia and Herzegovina". gcatholic.org. GCatholic. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

External links

-

Media related to Roman Catholicism in Bosnia and Herzegovina at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Roman Catholicism in Bosnia and Herzegovina at Wikimedia Commons