Sáhkku

| Years active | First documented in the 1800s, possibly played in the 1600s. Fallen somewhat out of use after the 1950s. |

|---|---|

| Genre(s) |

Board game Running-fight game Dice game |

| Players | 2 |

| Setup time | 30 seconds - 1 minute |

| Playing time | 5–60 minutes |

| Random chance | Medium (dice rolling) |

| Skill(s) required | Strategy, tactics, counting, probability |

| Synonym(s) | "Bircu", "Percc'", "The Devil's Game" |

Sáhkku is a board game invented by the Sami people. The game is particularly traditional among the Coast Sámi of northern Norway and Russia, but is also known to have been played in other parts of Sápmi.

Rules

Sáhkku is a running-fight game, which means that players move their pieces along a track with the goal of eliminating the other players' pieces. Many different versions of sáhkku have been played in different parts of Sápmi. The oral transfer of the sáhkku rules between generations was largely broken off during the 1900s (see Sáhkku today), so that modern rule sets have to rely on accounts written by outsiders. While valuable, these accounts are generally ambiguous or lacking when it comes to important parts of the gameplay. The following describes the rules that appear, according to written sources (see References), to have been widely practiced across different localities.

Board

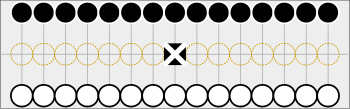

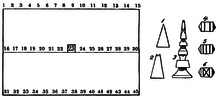

A sáhkku board traditionally consists of three horizontal lines intersected by a larger (variable) number of vertical lines. The pieces occupy the intersections of these horizontal and vertical lines. Some boards feature only the central horizontal line, or even no horizontal lines at all; however, the pieces still occupy the same notional intersections. The central point of the middle row, sometimes referred to as "the Castle", is indicated by a sáhkku-symbol ("X"), sun symbol, or other ornament.

Pieces

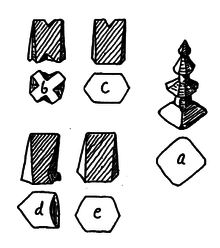

The game features several gálgut ("women") and olbmát ("men"), and one gonagas ("king"). The men and women are collectively referred to as “soldiers”, in some variants. The most common number of soldiers on each side is fifteen, but the number has varied according to the length of the board. The smallest number of soldiers described as being used is eight (Boris Gleb), and the highest is twenty. The latter is described as being "used in the Finnmark fisheries”, without any further geographic specification.[1]

In the sáhkku set donated by Isak Saba (pictured at the top of this article) the women's pieces had hooked-shaped tops, symbolizing the traditional North Sámi ladjogahpir hat which disappeared at the end of the 1800s because Christian missionaries and evangelists attacked the design for being a symbol of “the Devil’s horn”. The men's pieces were topped by cones. Elsewhere in Sápmi, the pieces appear to have had a simpler shape, both pieces ending in a sharpened “pyramid” which for the women had a notch cut into it at the top.[2]

As for the shape of the king, this varies a lot between game sets. At its simplest, the king piece is a tall, slender "pyramid" with four sides. More often, ornaments are cut into the sides. Many of the king pieces are so elaborately carved that the pyramidal shape is only suggested.[3]

Setup

At the beginning of the game, rows of men and women face each other on opposite rows of points. The Castle is occupied by the king . Dice are thrown to determine who begins the game. The player who first throws a sáhkku (X) may start.

Dice

The dice used for sáhkku are four-faced long dice or "stick dice". They are shaped like slightly elongated cubes whose short ends are sharpened to points so that they can only land on four of their sides. One side of each die bears the mark "X", the sáhkku symbol. The numbers on the other sides of the die have been known to vary. A common combination is X-II-III-0, but many other combinations have been known to exist.[4] The number of dice used has also varied, three being a rather usual number.[5] The dice are traditionally thrown in a bowl, rather than on the table.[6]

Movement

Pieces are moved in accordance with values shown on the dice after a throw. The rules for how to use the dice vary a lot, with some variants having very complex rules. In some variants one die may be used to move one piece only, while in other variants one may combine dice and add their values in order to move one piece a longer way.[7] In some rule sets it is said that each time a piece "lands" on a point after having moved according to the value of one die, it must perform the required action on that point (e.g. capture a soldier or recruit the king), even if it is to immediately (during the same turn) use the value of another die to move further.[8] In some variants, several pieces are allowed to occupy the same point, while in other rule sets this is unclear[9]

The soldiers

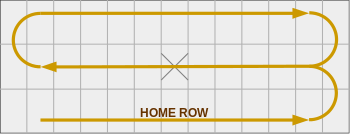

When the game begins, the soldiers are inactive — that is, unable to move. A player can activate a soldier by throwing a sáhkku. When activated, a soldier is moved one point ahead. After activation, dice are used to determine how many points soldiers can move ahead during their turn.[10] The soldiers move in a set pattern, which tends to be different from variant to variant. A not uncommon soldier's path is as follows: towards the player's right when they are in their home row (the row where they begin), towards the left when they are in the middle row, towards the right when they are in the enemy row, towards the left again the second time they move across the middle row, and repeat.[11]

The registered rule sets are unclear regarding whether activation is forced or free - i.e. if soldiers have to be activated in turn, starting with the player's foremost soldier, and continuing towards the back, or if any soldier in the home row may be activated regardless of its place in the row.

The king

The rules regarding the sáhkku king has been described differently by different authors, who have based their reports on gameplay in different parts of Sápmi. In all variants the king begins neutral, not controlled by either player.

Recruiting the king

In several registered variants, the first player to throw a sáhkku not only begins the game, but also immediately recruits the king, and is henceforth able to move it as they please. In other variants, the king is recruited by the first player to move one of their pieces onto the point currently occupied by the king.[12]

Moving the king

Several different rules for how one may move the king, have been documented. The following overview is not exhaustive.

- (A) In the Ráisá variant, the king moves like the soldiers of the player who currently controls it.[13]

- In the earliest written rules for sáhkku, written down by the researcher J. A. Friis in 1871,[14] the description of the king's movement is unclear. The text just states that the king "may be moved both forwards and backwards or to the right and left". The board drawn to illustrate this is turned so that "right and left" is identical to "forwards and backwards". Also, in the example of play, which showcases available alternative first moves after a throw of X-X-III by the player that has the king, the only given alternative that involves moving the king at all is to move it five, five, and three fields forwards into the enemy row, by which it captures the enemy soldiers on field 40 and 43. This description has been interpreted in many conflicting ways.

- (C) The king can move orthogonally right, left, up, and down. This means that when reaching an end of the middle row, it can choose to go up into the enemy row, or down into the home row, and also that it can move between the horizontal lines (f.ex. between field 42 and 12). These rules were noted to be used in Gussanjárga, where it was specified that it can not change direction while utilizing the value of one die (except when it rounds a corner between rows).[15]

The fate of the king

What happens to the king during the course of the game is also subject to large variation. In some variants of sáhkku, the loyalty of the king can change during the course of the game. The player not currently playing with the king may recruit it by moving a soldier onto the point currently occupied by the king. The king then becomes part of that player's army, until it is recruited by the opposing player again. In these variants of the game the king cannot itself be captured, only recruited.[16] In other variants, it is clearly written or indicated that a player who moves one of their soldiers onto a field occupied by the king may capture it and remove it from the board, like the ordinary soldiers.[17]

Capturing soldiers

The object of the game is to capture all of the opponent's soldiers, that is, to remove them from the board. An opponent's soldier is captured when a player moves a soldier, or the recruited king, onto a point occupied by the opponent. If the point in question is occupied by several opposing soldiers (in the cases where such "stacking" is allowed), all those soldiers are captured. A captured soldier is removed from the board, and not entered again. In Sámi, the act of capturing a soldier is referred to as goddit - "to kill".[18]

In some areas, the rules prohibited the capture of inactive soldiers,[19] while in other areas the capture of inactive soldiers has been allowed, or the rules were unclearly written. It is unknown what was the most widespread, or original, rule. Only the Gussanjárga variant is described explicitly as having a rule against capturing inactive soldiers.[20]

Variants

In the period when sáhkku was widely played, there were many versions of the game, with rules that differed slightly or substantially from each other. In the following we will first present some general rule variations, and then the only variant of sáhkku where the rules are known in full. Note that this variant is known to differ much from the rules of the game as played elsewhere in Sápmi.

General rule variations

Dividing the value of X

When using X to activate a soldier, that soldier is in many rule sets described as moving one field ahead. In the earliest recorded variant of sáhkku, however, the player moves soldiers four extra fields ahead upon activation.[21] This is essentially using the full value of the X (five) when activating. In this version it is also possible to divide the remaining four "points" of an X freely between the piece that was initially moved one field ahead, and a different piece. The rule set is unclear as regards how precisely this rule was applied.[22]

King’s children

Some versions of the game have included "king's children", two pieces placed four squares away from the king on either side. Their design indicates that each player had one such piece. Boards with markings for king’s children are known from Várjavuonna, Ohcejohka, Aanar and Peäccam - i.e. the easternmost part of the region where sáhkku was traditionally played.[23] The rules for using these pieces are lost.

It has been speculated [24] that the king’s children were imported from another Sámi board game, dablo. The rules for dablo king’s children are known: Both sides have a king’s child which is allowed to capture soldiers and each other, but are not allowed to capture kings, and cannot be captured by the soldiers.[25]

Playing from the same side of the board

A version of sáhkku has existed where the players' soldiers begin on same side of the board, although “the target of the game was [still] the same”.[26] The rules for this variant have been lost.

Ráisa sáhkku

The version of sáhkku is traditional to Ráisa municipality and the wider North Troms district around it. The rules were written down in the 1950s, and is the most complete sáhkku rule set known.[27]

Design

The board is designed with squares, as in chess, instead of with points formed by intersecting horizontal and vertical lines.[28] The king is often topped with a bishop’s crook.[29]

Board and setup

There are 3×13 squares, with twelve soldiers on each of the sides' home rows. In the starting position, the rightmost square (from the player's perspective) is left open.[30][31]

Dice

The Ráisa version calls for two dice, instead of three. The dice show X-I-II-III. X signifies "1" and never "5".[32] When a player throws X, they get to throw the die that showed X again, after they have used the sáhkku as they please. The sáhkku-giving dice(s) continue to be thrown again until it lands on another value than X.[33]

The soldiers' movement

It is not possible to move one individual piece by using the combined values of two or more dice. The movements of one piece must correspond to the value of one die only.[34] Soldiers, upon returning from the enemy's home row and having for the second time traversed the middle row, head back up into the enemy's home row again, never returning to their own home row.[35]

The king's movement

The king moves as described in the rules under (A).

Capturing

Inactive pieces can be captured.

History

Name

The North Sámi word "sáhkku", which is the name of both the game and the throw "X", means "fine", as in "mulct" or "penalty". Researchers have recorded that in one Lule Sámi area (Huhttán) the verb for playing sáhkku was "sakkotet". This is akin to sáhkkudit in modern Lule Sámi spelling, which means "to fine".[36] On the other hand, the North Sámi verb for playing sáhkku is sáhkostallat, which has no other meaning.[37]

The reasoning behind this name has been subject to some speculation and debate. One theory, put forth by Edmund Johansen, a veteran player of the game, to the French researcher Alan Borvo, is that "fine" in this case is a euphemism for "offering", used to avoid the wrath of Christian priests and evangelists. Sáhkku was considered a sinful game by such people, who saw traces of Sámi pre-Christian worship in it, and called it "The Devil's Game". According to Johansen's theory, it was in fact correct that the "King" piece had earlier been seen by players as representing a non-Christian deity in the game, and that the men's and women's "recruiting" of it implicitly happens through offerings.[38]

...this king may perfectly well have meant god with the signification the Sámit give to that word, i.e. a natural power, neither good nor bad, with whom one has to deal anyway by making offerings. In our language sáhkku means ‘penalty’. You may know the Sámit often give things new names just to avoid the minister’s wrath, so they could say penalty while they really thought of offering.”[39]

In support of this theory, Borvo has noted similarities between some wood-constructed Sámi sieidis (objects that are sacrificed to) and the shapes given to certain sáhkku king pieces.[40]

The game was also referred to as to play birccut, which simply means to play "dice" in North Sámi. An alternative name for the game in Skolt Sámi, percc', means the same.[41]

Related games

Sáhkku is part of a family of running-fight games that has its oldest traceable roots in the Eastern Mediterranean, and has been played at least since the 1300s. Members of this family bear obvious similarities to the Roman game tabula (the ancestor of backgammon), and the playing boards often have similarities to the board of tabula's probable ancestor, the Roman game XII scripta. There has been much scholarly debate, but no conclusive answers, as to how the games has spread from the Mediterranean to Northern Europe.[42]

African and Asian relatives

Tâb (also known as ‘’deleb’’ or ‘’sîg’’) is a game played in northern Africa and south-western Asia. A very similar game, tablan, is traditional to India.[43] When compared to sáhkku, tâb has somewhat different rules for moving pieces, and uses sticks in place of dice. The board is often larger, using four rows instead of three, although variants played with three rows also occur in Northern Africa. Pieces can be stacked and moved together, on the risk that all but one of them are lost if the stack is placed on a point where one of the pieces have been before. There is no king or kings’ children present in the game – that feature is exclusive to sáhkku.[44]

The first description of a game which is certain to be tâb occurred in 1694, that is some decades after Schefferus' book Lapponia described the use of sáhkku dice in Sápmi (see below).[45] However, a game assumed to be a predecessor of tâb was mentioned in a poem already in in 1310.[46] The researcher Thierry Depaulis argues that the game was played “by the 10th century at least”.[47]

European relatives

The game daldøs, played in parts of Denmark and southern Norway, is an obvious relative of sáhkku and tâb. Daldøs uses dice that are more or less identical to the sáhkku dice. Its rules are more similar to Ráisá sáhkku than to how sáhkku is generally played, but still different enough to be described as a fundamentally other game than Ráisá sáhkku. In place of moving pieces across points on a board, daldøs applies pegs that are moved from hole to hole on a board. Several pegs are not allowed to occupy the same hole (something that they obviously cannot, physically, do), and pegs belonging to the same player cannot pass one another. Furthermore, the pegs move in the same direction, as one player enters the middle row from the left, whereas the other enters the middle row from the right. The middle row is also one point longer than the home rows, a similarity shared with a version of tâb played in Algeria. Finally, daldøs features neither a king, nor king’s children.[48]

Daldøs is first mentioned in passing in a Danish work of fiction from 1876, the plot of which was set to the 1600s. The rules were not explained by the author, but an interested reader tracked down a person who knew the rules during the 1920s. The oldest surviving game set is no older than the early 1800s.[49]

In addition to sáhkku and daldøs, one other traditional running-fight board game survives in Northern Europe: the Icelandic game ad elta stelpur. This game differs from both of the other two by, among other things, featuring only two rows. The pieces move in the same direction, chasing each other around the board.[50]

The ancestor issue

It is generally assumed that tâb, daldøs and sáhkku have not developed separately, but are related to one another, and that the game has its origin in the Middle East. Several theories have been put forth as to how the tâb tradition travelled from such southern latitudes to the northernmost reaches of Sápmi.[51] Borvo referred to three opportunities as the ‘’Pomor track’’, the ‘’Kven track’’, and the ‘’Viking track’’,[52] while Depaulis argued for a ‘’Varangian track’’, and added a hypothetical ‘’Vandal track’’.[53]

Eastern tracks

The ‘’Varangian track’’ favored by Depaulis posits that Vikings who travelled in Eastern and Southeastern Europe between the 800s and 1000s may have learnt a game of the tâb family in Byzantium, brought it home, and that daldøs and sáhkku developed out of this. Depaulis notes that objections to this theory include that there is no evidence that the tâb type of games existed in the Middle East at such an early point in history, and that the east-faring Vikings were mainly from contemporary Sweden, whereas daldøs and sáhkku are generally known to have been played only within the contemporary borders of Norway and Denmark - the confirmed exceptions to the latter being localities in Finland and Russia that were immediate neighbors to the Coast Sámi of Norway.[54]

The ‘’Pomor track’’ posits that a tâb-type game was introduced to the Sámi by Russian merchants through the Pomor trade (ca. 1740-1917). The ‘’Kven track’’ suggests that the Kvens, immigrants from Finland who arrived in the 1700s and 1800s, brought the game with them. Sáhkku was generally played on the North Coast of Sápmi, the areas where the Sámi were most involved in the Pomor trade, and which were targeted by Kven immigration. Borvo notes that the absence of any traditional tâb-type game in Russia, except the sáhkku of the Russian Sámi, speaks against the Pomor track, and that the same applies for the Kven track since the Finns have no tâb-type games of their own.[55] Depaulis additionally doubts the Kven and Pomor tracks because he finds it hard to imagine that the Norwegians and Danes based their daldøs game on the Sámi sáhkku game, but he does not give any arguments as to why this is any less likely than the opposite; nor does he address the possibility that daldøs and sáhkku could have developed separately, but with roots in the same Middle Eastern progenitor.[56]

Western tracks

The ‘’Viking track’’ preferred by Borvo posits that west-faring Norse seafarers learnt the game in the south, adapted it to daldøs, and introduced the game to the Sámi, who again made sáhkku from that basis. If this is to have happened in the Viking Age, táb-type games must be older than what written sources indicate. Depaulis adds to Borvo’s ‘’Viking track’’ theory by pointing to relationships between the Western Vikings (of contemporary Denmark and Norway) and Islamic Spain during the 800s,[57] although this again presupposes that tâb is older than what written sources indicate. Borvo notes that the absence of sáhkku and daldøs traditions on the long stretch of coastline between Jæren in the south and Ivguvuotna in the north does not speak in favor of this theory, or indeed any theory presupposing that tâb-type games were at one point played along the entire western coast of Scandinavia. He speculates that the game may have died out south of Ivgovuotna because it was only in the far north that the Coast Sámi made certain innovations to the game that made it interesting enough to keep playing for centuries (i.e. the king and king’s children, the increased freedom of pieces to move). This explanation presses the question of why the less “exciting” version, daldøs, did survive in southern Scandinavia.[58]

The general idea that the game spread from Africa and Asia along the west coast of Europe, gets some support from the findings of what is assumed to be related game boards stemming from seafaring communities around southern England: What appears to be a board for a game in the same family was found in the wreckage of the English warship Mary Rose, which sank south of England in 1545.[59] Likewise, a 13th-century manuscript from Dorset includes a drawing of a game board which is seen as having probably been used to play a game of this family.[60] This last finding predates the first mention a game called "tâb", and both findings predate the first description of tâb. Like daldøs, both the Mary Rose game board and the Dorset board feature an “extra” point on the middle row.[61]

The Northern track

Finally, Depaulis points to a speculative opposite direction of this game family’s spread – the ‘’Vandal track’’, in which a three-rowed running-fight game was brought from the North to Northern Africa by Vandals in the period 400-500 CE, and spread from there to the Middle East. This would imply that tâb developed from a North European game tradition, and not the other way around. It also implies that sáhkku and its northern relatives may be direct descendants of the original North European running-fight game.[62]

The lack of sources and artifacts

All of these theories have in common that there is little to no textual or material evidence to back any of them up. In addition to the sparse written sources, a key difficulty is that the tâb types of game were generally made from “ephemeral” materials which do not leave long-lasting material remains: often wood in the North,[63] and in the Middle East the game has often simply been drawn in the sand, using twigs and stones for pieces and dice.[64]

As regards sáhkku, this lack of material artifacts problem was made worse by Nazi Germany's burning of Finnmark and North Troms in 1944-45. Operation Nordlicht targeted the region with scorched earth tactics, and destroyed the pre-WWII material culture of the Coast Sámi almost in its entirety. The Wehrmacht had done the same in Finnish Lapland before initiating the destruction of Finnmark and North Troms. Since this calamity struck precisely the region where sáhkku had mainly been played, it is unlikely that any game sets older than 1944 survived, except those that were stored in museums outside of the region.

The development and spread of sáhkku

First mentions of the game

It is unknown how long sáhkku has been played among the Sámi. The earliest mention in writing of what could be sáhkku was made by Johannes Schefferus in his book Lapponia (1673), where he states that the Sámi use dice that he describes as having the shape and markings of contemporary sáhkku dice. He credits Olaus Sirma with giving him this information. Schefferus did not, however, describe any game similar to sáhkku.[65] After this, it is not until 1841 when a written source speaks of a game called sáhkku being played, then in the Lule Sámi area. This is generally assumed to have been the same game as the one described here, although no further description of that game was given.[66] The first unambiguous description of sáhkku was made by J. A. Friis in 1871, who accounted in detail for a version played in Finnmark (see drawing below).

Introduction of the king and the king’s children

Friis’ description shows that the king piece unique to this tâb-type game had by then been invented, but he makes no mention of the king’s children. However, the oldest existing sáhkku board (1876) features markings that indicate where to place the king’s children, although the set does not include the actual pieces. The king’s children are not described in literature until the 1930s and 1940s.[67] The oldest existing complete sáhkku set, donated to a museum by Isak Saba in 1906 (depicted at the top of this article), includes soldiers, the king, three dice and a board with markings for where to place the king and possibly for king's children. There also exist non-complete sets of pieces – soldiers, king, and king’s children – which date back to the 1800s.[68]

Michaelsen and Borvo argue that the introduction of the king into this relative of tâb could have been inspired by the Sámi board game tablut, which features a king piece shaped in a similar way to certain sáhkku king pieces.[69] Likewise, Michaelsen speculates that the king's children may have been inspired by the Sámi board game dablo which has such pieces. Tablut was documented in the 1700s, while dablo was mainly documented in the 1800s and early 1900s. Both of these are, like sáhkku, specifically Sámi board games that belong to a larger family of games – tablut is of the North European tafl family, while dablo is of the alquerque family that has its earliest traceable roots in the Middle East, and came to Europe through Spain.[70]

Geographical distribution of the game

While descriptions of tablut and dablo are generally from the South Sámi area, more precisely Jämtland and southern Swedish Lapland,[71] sáhkku has to our knowledge generally been played on the coast of the North Sámi and Skolt Sámi area, in a region ranging from Ivguvuotna to Peäccam. According to Anders Larsen the game was also played by coastal Sámi further south, in Nordland county.[72] Hence, sáhkku has at least during the last two centuries mainly been played in the core area of the Coast Sámi culture. The game is, however, also known to have been played in northern parts of Finnish Lapland, more precisely Ohcejohka and Aanar, and among the Skolt Sámi of contemporary Norway, Finland and Russia.[73] See also the above mention of a game called sáhkku being played among the Lule Sámi of Huhttán, Swedish Lapland.[74]

Outside of Sápmi, what is speculated to be a sáhkku king has been found in Spitzbergen (1890), although this piece could also be a chess king.[75] It has, however, been documented by V. Carlheim-Gyllensköld (cited by researcher Peter Michaelsen[76]) that Russians in Spitzbergen did indeed play sáhkku in the 1890s. This variant employed 2*13 soldiers and one king, on a board with 3*13 lines. Uniquely, they also used six-sided dice. One of the sides was marked “X”, one was blank, and the remaining sides marked with strokes (I-II-III-IIII). The “X” was referred to by the Russians as sakko, a name confirming that these Russians had indeed learnt the game from the Sámi, or alternately that they themselves were Russian Sámi.

Sáhkku today

Sáhkku was considered a sinful game by Christian missionaries and Laestadian evangelists, since it was suspected of containing elements of pre-Christian worship.[77] As a result of this religious pressure, official Norwegianization policy’s pressure to abandon all aspects of Sámi culture and identity, the destruction of Coast Sámi material culture during World War II, and the increasing availability of new forms of entertainment, sáhkku fell out of use in Sámi communities after the 1950s. In some localities the game was still played regularly during the 1960s, but it has not been played widely since then.[78]

Sámi cultural revitalization began to pick up speed during the 1970s and 1980s, and in this period some copies of old sáhkku game sets were made. During the 1980s and 1990s the game began to be sporadically played again in the Lágesvuotna region of eastern Finnmark, drawing on the competence of elders who still knew how to play.[79] Still, unlike many other aspects of Sámi culture, sáhkku has yet to experience a genuinely large-scale revival among the Sámi. In the period around the change of the millennium, researchers began to take an interest in sáhkku and its history, leading to several articles published about the subject in English and French. Since then, several small internet-based actors based south of Sápmi have begun to offer sáhkku sets for sale, but the game is still not widely available on the market.

See also

- Daldøs, a south Scandinavian relative of Sáhkku.

- Tâb, a possible Middle Eastern relative of Sáhkku.

- Tablut, the Sámi version of the Scandinavian Tafl games, from which the rules of modern Hnefatafl are drawn. Although the name is similar, tablut is not a relative of tâb.

- Dablot Prejjesne, a Sámi game similar to alquerque and draughts, but like Sáhkku utilizing pieces called the "king" and "kings' children".

Notes

- ↑ Borvo 2001, p. 43

- ↑ Borvo 2001, p. 43

- ↑ Borvo 2001, p. 44

- ↑ Borvo 2000, p. 42

- ↑ Friis 1871: 164-167; Borvo 2001: 49-52

- ↑ Michaelsen 2000, p. 25

- ↑ Friis 1871: 164-16; Borvo 2001: 49-52

- ↑ Friis 1871: 164-167; Michaelsen 2000, p. 23

- ↑ Friis 1871; Borvo 2001; Michaelsen 2000, p. 22-24

- ↑ Friis 1871; Borvo 2001; Michaelsen 2000, p. 22-24

- ↑ Friis 1871: 164-167; Borvo 2001: 49-52

- ↑ Borvo 2001, p. 44, 49-52; Friis 1871: 164-167

- ↑ Michaelsen 2000, p. 22-24

- ↑ Friis 1871: 164-167

- ↑ Borvo 2001: 49-52

- ↑ Borvo 2001: 49-52; Michaelsen 2000, p. 22-24

- ↑ Borvo 2001: 49-52

- ↑ Friis 1871, p. 167

- ↑ Borvo 2001, p. 34

- ↑ Borvo 2001: 49-52

- ↑ Michaelsen 2000.

- ↑ Friis 1871: 164-167

- ↑ Borvo 2001, p. 44

- ↑ Michaelsen 2000, p .28

- ↑ Michaelsen 2010, p. 218-221

- ↑ Borvo 2001: 49-52

- ↑ Michaelsen 2000

- ↑ Borvo 2001, p. 43

- ↑ Borvo 2001, p. 44

- ↑ Meiland, cited in Borvo 2001, p. 44

- ↑ Michaelsen 2000, p. 20, citing Mejland 1953

- ↑ Michaelsen 2000, p. 22-24

- ↑ Michaelsen 2000, p. 22-24; Borvo 2001

- ↑ Borvo 2001, p. 42

- ↑ Michaelsen 2000, p. 22-24

- ↑ Michaelsen, p. 19

- ↑ Larsen 1950, p. 171. For comparison, the modern North Sámi word for "to fine" is sáhkkohit'.

- ↑ Borvo, p. 33

- ↑ Johansen quoted in Borvo, p. 45

- ↑ Borvo 2001, p. 46

- ↑ Borvo, p. 42, 48

- ↑ Depaulis “Arab game”, 2001, p. 82

- ↑ Walker, 2011

- ↑ Depaulis “Arab game”, 2001

- ↑ Depaulis "Jeux" 2001, p 56

- ↑ Depaulis "Jeux" 2001, p 54

- ↑ Depaulis “Arab game”, 2001, p. 82

- ↑ Østergaard & Gaston 2001; Michaelsen 2001, p. 24-25

- ↑ Michaelsen 2001, p. 19-21

- ↑ Bell 1979, p. 37-38

- ↑ Depaulis “Arab game”, 2001, p. 82

- ↑ Borvo 2001, p. 46-47

- ↑ Depaulis “Arab game”, 2001, p. 82

- ↑ Depaulis “Arab game” 2001, p. 78-80

- ↑ Borvo 2001, p. 46-7

- ↑ Depaulis “Arab game” 2001, p. 77

- ↑ Depaulis “Arab game” 2001, p. 81-

- ↑ Borvo 2001, p. 46

- ↑ "Daldøs in 16th century England". Levingston's Board Game Blog. January 2010. Retrieved 2015-12-08.

- ↑ Michaelsen 2001, pp 26–27.

- ↑ Borvo 2001, p. 46

- ↑ Depaulis 2001 “Arab game”, p. 81-82

- ↑ Although kings could be made with more sturdy material such as reindeer horn, and in one noted case with lead. See Michaelsen 2000 p. 26 (citing Mejland)

- ↑ Depaulis “Arab game” 2001, p. 79

- ↑ Borvo 2001, p. 37; Casaux, p. 90; Depaulis “Arab game” 2001, p. 80

- ↑ Borvo 2001, p. 42; Michaelsen 2000, p. 19

- ↑ Borvo 2001, p. 34-35, 38

- ↑ Borvo 2001, p. 35

- ↑ Borvo, p. 44; Michaelsen 2000, p. 28.

- ↑ Michaelsen 2010

- ↑ Although Anders Larsen described a game called cuhkkálávdi, essentially dablo without officer pieces and on a smaller board, as being played by the Coast Sámi of Northern Troms, cf. Michaelsen 2010, p. 218, 220; Larsen 1950, 171

- ↑ Larsen 1950, p. 171.

- ↑ Borvo 2001, p. 39

- ↑ Borvo 2001, p. 42; Michaelsen 2000, p. 19

- ↑ Borvo 2001, p. 42

- ↑ Michaelsen 2003, p. Note that the article gives “Siberia” instead of “Spitzbergen”, but this is a typo – the book of Carlheim-Gyllensköld that Michaelsen refers to, specifically concerns Spitzbergen

- ↑ Borvo 2001, p. 33

- ↑ Borvo 2001, p. 39-40

- ↑ Michaelsen 2000, p. 20; Hansen 2013

References

Sámi

- Larsen, Anders (1950), Mearrasámiid birra. In Mearrasámiid birra - ja eará čállosat / Om sjøsamene - og andre skrifter. Edited by Ivar Bjørklund and Harald Gaski (2014)., 4, Karasjok: ČálliidLágádus SÁMIacademia

Danish and Norwegian

- Friis, J. A. (1871), Lappisk mytologi. Eventyr og folkesagn., Christiania: Alb. Cammermeyer

- Hansen, Jostein (2013), "Samisk avdeling og samiske studenter på Lærerutdanninga i Alta" in Lund, S. "Samisk skolehistorie 6", Karasjok: Davvi Girji

- Mejland, Yngvar (1953), "Sakko", Bygd og by, Oslo, 8

- Michaelsen, Peter (2000), "Daldøs og Sakku - to gamle nordiske spil", ORD & SAG, Aarhus: Institut for Jysk Sprog- og Kulturforskning, 19: 15–29, ISSN 0108-8025

German

- Lagercrantz, Eliel (1939), Lappischer Wortschatz, Helsinki

English

- Borvo, Alan (2001), "Sáhkku, The "Devil's Game"" (PDF), Board Games Studies, Leiden: CNWS Publications, 4: 33–52, ISBN 90-5789-075-5, ISSN 1566-1962

- Depaulis, Thierry (2001), "An Arab Game in the North Pole?" (PDF), Board Games Studies, Leiden: CNWS Publications, 4: 77–82, ISBN 90-5789-075-5, ISSN 1566-1962

- Michaelsen, Peter (2001), "Daldøs, an almost forgotten dice board game" (PDF), Board Games Studies, Leiden: CNWS Publications, 4: 19–31, ISBN 90-5789-075-5, ISSN 1566-1962

- Michaelsen, Peter (2003), "On some unusual types of stick dice.", Board Games Studies, Leiden: CNWS Publications, 6: 9–25

- Michaelsen, Peter (2010), "Dablo - A Sámi game.", Variant Chess, St. Leonards-on-the-Sea, East Sussex, 64: 218–221

- Walker, Damian (2011), Tablan, 43, Cynningstan. Traditional board game series

- Østergaard and Gaston, Eric and Anne (2001), "Daldøs — the rules" (PDF), Board Games Studies, Leiden: CNWS Publications, 4: 15–17, ISBN 90-5789-075-5, ISSN 1566-1962

French

- Cazaux, Jean-Louis (2012), Les jeux des parcours. A travers les siecles et les continentes., Toulouse: Pionissimo, pp. 87–90, ISBN 978-2-9541313-1-3

- Depaulis, Thierry (2001), "Jeux de parcours du monde arabo-musulman (Afrique du Nord et Proche-Orient)" (PDF), Board Games Studies, Leiden: CNWS Publications, 4: 53–76 (English summary p 149), ISBN 90-5789-075-5, ISSN 1566-1962