Football pitch

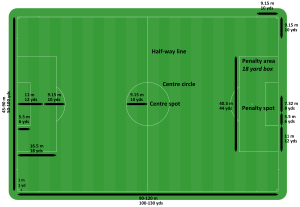

A football pitch (also known as a football field[1] or soccer field) is the playing surface for the game of association football. Made of turf (grass) or artificial turf, its dimensions and markings are defined by Law 1 of the Laws of the Game, "The Field of Play".[2]

All line markings on the pitch form part of the area which they define. For example, a ball on or above the touchline is still on the field of play, and a foul committed over the 16.5-metre (18-yard) line has occurred in the penalty area. Therefore, a ball must completely cross the touchline to be out of play, and a ball must wholly cross the goal line (between the goal posts) before a goal is scored; if any part of the ball is still on or above the line, the ball is still in play.

The field descriptions that apply to adult matches are described below. Note that due to the original formulation of the Laws in England and the early supremacy of the four British football associations within IFAB, the standard dimensions of a football pitch were originally expressed in imperial units. The Laws now express dimensions with approximate metric equivalents (followed by traditional units in brackets), but use of the imperial units remains common in some countries, especially in the United Kingdom.

Pitch boundary

The pitch is rectangular in shape. The longer sides are called touchlines. The other opposing sides are called the goal lines. The two goal lines must be between 45 and 90 m (50 and 100 yd) and be the same length.[3] The two touch lines must also be of the same length, and be between 90 and 120 m (100 and 130 yd) in length.[3] All lines must be equally wide, not to exceed 12 centimetres (5 in).[3] The corners of the pitch are marked by corner flags.[4]

For international matches the field dimensions are more tightly constrained; the goal lines must be between 64 and 75 m (70 and 80 yd) long and the touchlines must be between 100 and 110 m (110 and 120 yd).[3] In March 2008 the IFAB attempted to standardise the size of the football pitch for international matches and set the official dimensions of a pitch to 105 m long by 68 m wide.[5] However, at a special meeting of the IFAB on 8 May 2008, it was ruled that this change would be put on hold pending a review and the proposed change has not been implemented.[6]

Although the term goal line is often taken to mean only that part of the line between the goalposts, in fact it refers to the complete line at either end of the pitch, from one corner flag to the other. In contrast, the term byline (or by-line) is often used to refer to that portion of the goal line outside the goalposts. This term is commonly used in football commentaries and match descriptions, such as this example from a BBC match report; "Udeze gets to the left byline and his looping cross is cleared..."[7]

Goals

Goals are placed at the centre of each goal-line.[8] These consist of two upright posts placed equidistant from the corner flagposts, joined at the top by a horizontal crossbar. The inner edges of the posts must be 7.32 metres (8 yd) apart, and the lower edge of the crossbar must be 2.44 metres (8 ft) above the ground.[9] Nets are usually placed behind the goal, though are not required by the Laws.

Goalposts and crossbars must be white, and made of wood, metal or other approved material. Rules regarding the shape of goalposts and crossbars are somewhat more lenient, but they must conform to a shape that does not pose a threat to players. Since the beginning of the football there have always been goalposts, but the crossbar wasn't invented until 1875, where a string between the goalposts was used.[10]

A goal is scored when the ball crosses the goal line between the goal-posts, even if a defending player last touched the ball before it crossed the goal line (see own goal). A goal may, however, be ruled illegal (and void by the referee) if the player who scored or a member of his team commits an offence under any of the laws between the time the ball was previously out of play and the goal being scored. It is also deemed void if a player on the opposing team commits an offence before the ball has passed the line, as in the case of fouls being committed, a penalty awarded but the ball continued on a path that caused it to cross the goal line.

History of football goals and nets

Football goals were first described in England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. In 1584 and 1602 respectively, John Norden and Richard Carew referred to "goals" in Cornish hurling. Carew described how goals were made: "they pitch two bushes in the ground, some eight or ten foote asunder; and directly against them, ten or twelue [twelve] score off, other twayne in like distance, which they terme their Goales".[11] The first reference to scoring a goal is in John Day's play The Blind Beggar of Bethnal Green (performed circa 1600; published 1659). Similarly in a poem in 1613, Michael Drayton refers to "when the Ball to throw, And drive it to the Gole, in squadrons forth they goe". Solid crossbars were first introduced by the Sheffield Rules. Football nets were invented by Liverpool engineer John Brodie in 1891,[12] and they were a necessary help for discussions about whether or not a goal had been scored.[13]

Penalty and goal areas

Two rectangular boxes are marked out on the pitch in front of each goal.

The goal area (colloquially the "six-yard box"), consists of the area formed by the goal-line, two lines starting on the goal-line 6 yards (5 m) from the goalposts and extending 6 yards (5 m) into the pitch from the goal-line, and a line joining these. Goal kicks and any free kick by the defending team may be taken from anywhere in this area. Indirect free kicks awarded to the attacking team within the goal area must be taken from the point on the line parallel to the goal line nearest where an incident occurred; they can not be taken further within the goal-area. Similarly drop-balls that would otherwise occur in the goal area are taken on this line.

The penalty area (colloquially "The 18-yard box" or just "The box") is similarly formed by the goal-line and lines extending from it, however its lines commence 18 yards (16 m) from the goalposts and extend 18 yards (16 m) into the field. This area has a number of functions, the most prominent being to denote where the goalkeeper may handle the ball and where a foul by a defender, usually punished by a direct free kick, becomes punishable by a penalty kick. Both the goal and penalty area were formed as halfcircles until 1902.[13]

The penalty mark is 11 metres (12 yd) in front of the very centre of the goal; this is the point from where penalty kicks are taken. The penalty arc (colloquially "the D") is marked from the outside edge of the penalty area, 9.15 metres (10 yd) from the penalty mark; this, along with the penalty area, marks an exclusion zone for all players other than the attacking kicker and defending goalkeeper during a penalty kick.

Other markings

The centre circle is marked at 9.15 metres (10 yd) from the centre mark. Similar to the penalty arc, this indicates the minimum distance that opposing players must keep at kick-off; the ball itself is placed on the centre mark.[13] During penalty shootouts all players other than the two goalkeepers and the current kicker are required to remain within this circle.

The half-way line divides the pitch in two. The half which a team defends is commonly referred to as being their half. Players must be within their own half at a kick-off and may not be penalised as being offside in their own half. The intersections between the half-way line and the touchline can be indicated with flags like those marking the corners – the laws consider this as an optional feature.[4]

The arcs in the corners denote the area (within 1 yard of the corner) in which the ball has to be placed for corner kicks; opposition players have to be 9.15 m (10 yd) away during a corner, and there may be optional lines off-pitch 10 yards away from the corner arc on the goal- and touch-lines to help gauge these distances.[8]

Turf

Grass is the normal surface of play, although artificial turf may sometimes be used especially in locations where maintenance of grass may be difficult due to inclement weather. This may include areas where it is very wet, causing the grass to deteriorate rapidly; where it is very dry, causing the grass to die; and where the turf is under heavy use. Artificial turf pitches are also increasingly common on the Scandinavian Peninsula, due to the amount of snow during the winter months. The strain put on grass pitches by the cold climate and subsequent snow clearing has necessitated the installation of artificial turf in the stadia of many top-tier clubs in Norway, Sweden and Finland. The latest artificial surfaces use rubber crumbs, as opposed to the previous system of sand infill. Some leagues and football associations have specifically prohibited artificial surfaces due to injury concerns and require teams' home stadia to have grass pitches. All artificial turf must be green and also meet the requirements specified in the FIFA Quality Concept for Football Turf.[14][15][16]

References

- ↑ For example, George Cuming, Manager Project Future Referees (9 December 2009). "Evolution of football field markings". Asian Football Confederation.

- ↑ "Premiership football stadiums". TalkFootball. Retrieved 6 January 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 "Laws of the Game 2011/2012" (PDF). FIFA. p. 7. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- 1 2 "Laws of the Game 2011/2012" (PDF). FIFA. p. 8. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- ↑ "Goal-line technology put on ice". IFAB media release. FIFA. 8 March 2008. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- ↑ "FIFA Circular 1145" (PDF). FIFA media release. FIFA. 22 May 2008. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- ↑ Match report BBC

- 1 2 "Laws of the Game 2011/2012" (PDF). FIFA. p. 9. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- ↑ http://www.fifa.com/mm/document/footballdevelopment/refereeing/81/42/36/log2013en_neutral.pdf

- ↑ Hornby, Hugh (2000). Football. Dorling Kindersley Ltd. p. 12. ISBN 8778267633.

- ↑ Richard Carew. "EBook of The Survey of Cornwall". Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 3 October 2007.

- ↑ Herbert, Ian (7 July 2000). "Blue plaque for man who invented football goal net". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 6 April 2010. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- 1 2 3 Hornby, Hugh (2000). Football. Dorling Kindersley Ltd. p. 13. ISBN 8778267633.

- ↑ "Laws of the Game 2011/2012" (PDF). FIFA. p. 6. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- ↑ "FIFA Quality Concept for Football Turf" (PDF). FIFA. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ↑ "FIFA Quality Concept" (PDF). Retrieved 14 February 2012.