Southern Italy autonomist movements

There are various regional Southern Italy autonomist movements, covering the political spectrum from socialist to Bourbon monarchist.

Since the fall of the Roman Empire, Southern Italy often experienced distinct historical developments when compared to Northern Italy. As a result, it has developed distinctive cultures and identities that persist to this day. After the Kingdom of Italy took control of the south in 1861, as well as the rest of Italy apart from present day Veneto, Friuli-Venezia Giulia and Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol, which were annexed later, it took many years before resistance died down and central authority was established. During World War II there were fresh attempts by Sicilians to achieve independence. Political groups continue to advocate greater autonomy, or sometimes even independence, for southern Italy.

However, the demand for autonomy or independence, with the exception of the island of Sardinia[1][2] which is often included as part of Southern Italy, is now weaker in the South than in the North.[3]

This article does not include Sardinia nor its own nationalist movement, being grounded on different historical and cultural reasons and backgrounds.

Historical background

After the disintegration of the Western Roman Empire in 476, Italy and Sicily came under the control of successive Germanic invaders such as the Ostrogoths,[4] Lombards[5] and Franks.[6] However, the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire continued to retain strong links with Venice, the south of Italy and Sicily. For long periods the southern territories were under Greek Byzantine control. Following the expansion of Islam, Sicily (as with Spain) was progressively conquered by the Arabs from the mid-9th to the mid-10th centuries, and Arab advances were introduced to Europe.[7]

In the 11th century Norman invaders took control of southern Italy, captured Messina in 1061, and after extended maneuvers and sporadic fighting took Syracuse in 1086.[8] The Normans adapted to the sophisticated oriental culture of the island, which for a while was the wealthiest country in Europe and the main channel for bringing advanced eastern knowledge and ideas to western Europe.[9] Various dynastic changes occurred in the ensuing centuries, with Sicily and Naples coming under control of the Swabian Hohenstaufen Dynasty, then the French Angevin Dynasty. In 1282 Peter III of Aragon, son-in-law of the last Hohenstaufen king, gained control of Sicily although the Angevins retained control of the Kingdom of Naples.

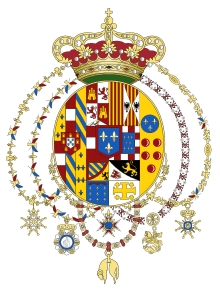

In 1442 King Alfonso V of Aragon reunified the Kingdom of Sicily and the Kingdom of Naples into the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. For most of its existence, the Kingdom of Two Sicilies was ruled directly by Aragon, then by Spain, or was a kingdom subordinate to Spain. In 1713 Spain and both Sicilies passed to Philip, Duke of Anjou, who founded the Spanish branch of the House of Bourbon. Apart from a short period of Napoleonic rule between 1805 and 1815, the kingdom was ruled by Bourbon princes until 1861 when it was annexed by the Kingdom of Italy after the Expedition of the Thousand led by Giuseppe Garibaldi.[10]

As a result of its colourful history and geography, Sicily has developed some distinctive qualities. Compared to the other regions of Italy, cultural similarities to the Greeks, Spaniards and Eastern Mediterranean people are more obvious. Unlike much of the other Italian regions, Sicilian cuisine has strong Greek, Arab and Spanish influences[11] and is more typical of the Mediterranean diet.

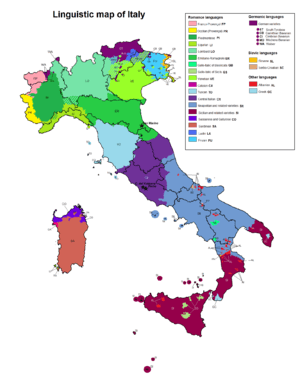

Languages

With the exception of Sardinian, most of the languages traditionally spoken in southern Italy are grouped as dialects of the Neapolitan and Sicilian languages. Like the Gallo-Romance languages spoken in the north, these dialects are different from standard Italian, though the Neapolitan variants are similar to the central language group which includes the Tuscan language on which standard Italian is based. Sicilian has a very strong Greek-Arab substratum, which give the languages many distinct sounds and flavors not typical of Italian.[12]

Revolutions and Rebellions 1806–1861

French Revolution, Empire, Reaction

The French Revolution (1789–1799) created a fundamental change in political thought in Europe, establishing the principle of rule by representatives of the people. During the wars to ensure the survival of the French republic, the French army led by the Corsican Napoleon Bonaparte occupied northern Italy and founded the Cisalpine Republic with its capital at Milan.[13] After seizing power from the republicans, Napoleon was crowned King of Italy with the Iron Crown of Lombardy in 1805. In 1806 Napoleon dispatched a French army to the south of Italy, installing his brother Joseph king of Naples and Sicily. Two years later Joseph was replaced as king by Joachim Murat who ruled until 1815.[14]

Ferdinand IV of Naples fled to Palermo in 1806 and managed to retain control of Sicily under British naval protection. He appointed his son Francis regent, and at the insistence of Lord William Bentinck, the British minister, allowed a reform of the constitution on English and French lines in 1812. However, following the defeat of Napoleon, Ferdinand violated his oath and in 1816 abolished the Sicilian constitution, imposing a reactionary system of aristocratic government.[15]

Rebellion of 1820

In July 1820 a military revolt broke out in Naples, the mutineers cheering for the king and the constitution. A simultaneous revolt in Sicily having been repressed, General Guglielmo Pepe, who had previously fought for Napoleon, was appointed inspector-general of the army. While Pepe hesitated as to what course he should follow Ferdinand promised a constitution on the model of the Spanish Constitution of 1812. The king, who had no intention of respecting the constitution, went to Laibach to confer with the sovereigns of the Holy Alliance assembled there, leaving his son as regent. While the regent dallied with the Liberals, Ferdinand obtained the loan of an Austrian army with which to restore absolute power. Pepe, who in parliament had declared in favour of deposing the king, took command of the army and marched north against the Austrians. He attacked them at Rieti in March, 1821 but his raw levies were repulsed.

After the revolt had disintegrated Ferdinand dismissed the parliament and inaugurated an era of savage persecution, supported by spies and informers, against the Liberals and Carbonari.[16]

Rebellion of 1848

In 1848 fresh tides of revolution swept over Europe. A revolt led by Sicilian nobles broke out in Palermo on 12 January 1848, the birthday of Ferdinand II of the Two Sicilies. The leaders reinstated the democratic constitution of 1812. On 3 September 1848 a naval flotilla shelled the city of Messina for eight hours after its defenders had already surrendered, killing many civilians and earning the King the nickname "Re' Bomba" ("King Bomb"). After a savage campaign, the Neapolitan army under the command of General Carlo Filangieri defeated the rebels, who capitulated on May 15, 1849.

The head of the state during this period was Ruggero Settimo (Ruggeru Sèttimu in Sicilianu), who escaped to Malta after the island capitulated. After the success of the Risorgimento movement during 1860 and 1861, he was offered the position of the President of the Senate of the newly created Parliament of the Kingdom of Italy but he declined for health reasons, dying two years later.[17]

Risorgimento

.jpg)

On May 11, 1860, Garibaldi and a cadre of about a thousand Italian volunteers landed near Marsala on the west coast of Sicily. Near Salemi, Garibaldi's army attracted scattered bands of rebels, and the combined forces defeated the opposing army at Calatafimi on May 13. Within three days, the invading force had swelled to 4,000 men. On May 14, Garibaldi proclaimed himself dictator of Sicily in the name of Victor Emmanuel II of Italy. After a series of hard-fought battles, Garibaldi advanced upon Palermo. On May 27, the force laid siege to the Porta Termini of Palermo, while a mass uprising of street and barricade fighting broke out within the city.

Neapolitan general Ferdinando Lanza, arriving in Sicily with some 25,000 troops, bombarded Palermo nearly to ruins. However, with the intervention of a British admiral, an armistice was declared. The Neapolitan troops departed and the town surrendered to Garibaldi and his much smaller army. Six weeks later, Garibaldi attacked Messina. Within a week its citadel surrendered.

Having conquered Sicily, Garibaldi crossed the Straits of Messina. The garrison at Reggio Calabria promptly surrendered. Progressing northward, the populace everywhere hailed him and military resistance faded. At the end of August Garibaldi was at Cosenza, and on September 5 at Eboli, near Salerno. Meanwhile, Naples had declared a state of siege, and on September 6 the king gathered the last 4,000 troops (with many mercenaries) still faithful to him and retreated over the Volturno river. The next day Garibaldi, with a few followers, entered Naples by train, whose people openly welcomed him as had happened before in Salerno and other southern cities[18]

Post-unification unrest and first social improvements

The newly united Kingdom of Italy of 1861 was very poor. The Borbons had left a southern Italy where there was little industry, bad roads, few railways, low literacy, and only a small percent of wealthy southern Italians had the right to vote. Most people in the Mezzogiorno (the former Two Sicilies) lived in extreme poverty.[3]

Because of the 'Garibaldini' war against the bands of Mafia criminals in the sicilian mountains, the economic situation in the island deteriorated in the mid-1860s and an anti-Savoy revolt pushing for Sicilian independence erupted in 1866 at Palermo. The city was soon bombed by the Italian navy. Fourteen battalions of Italian soldiers led by Raffaele Cadorna landed on 16 September, killing some civilian insurgents and quickly regaining possession of the island.[19] A limited, but long guerrilla campaign against the unionists (1861–1871) took place throughout southern Italy, and in Sicily, inducing the Italian governments to a severe military response. These insurrections were unorganized, and were considered by the Government as operated by "brigands" (brigantaggio): but some historians pinpoint that they were ruled by the Papal State in Rome, as a form of defense until its fall in 1870 (when Rome was conquered by Victor Emmanuel II, suddenly the brigantaggio disappeared). Ruled under martial law for several years, Sicily (and southern Italy) was the object of a harsh repression by the Italian army.

Many public works were initiated in southern Italy in order to build roads and railways that had been neglected by the Borbons. The schools were opened to all the poor, as well as a new sanitary health system with hospitals that boomed the population (infant mortality dwindled in 10 years from 1865 to 1875). The first steps toward the creation of a pension system for all the southern Italians were done, but its full implementation was completed only in the 1930s (while illiteracy disappeared gradually by the turn of the century).Some cities benefited of the early stages of industrialization, mainly shipbuilding in Naples and Taranto.

But faced with competition from northern industry, new forms of taxation and the new Kingdom's extensive military conscription, the economy of the Mezzogiorno partially collapsed, leading to an unprecedented wave of emigration related even to the demographic boom[20] The rise of leftist organisations of workers and peasants known as the Fasci Siciliani caused the Italian government to impose martial law again in 1894.[21][22]

An 1881 census found that over 1 million southern day-labourers were chronically under-employed and were very likely to become seasonal emigrants in order to economically sustain themselves. The 1910 Commission of Inquiry into the South indicated that the Italian government had failed to ameliorate the severe economic differences and the limitation of voting rights to those with sufficient property allowed rich landowners to exploit the poor.[23][24]

The Mafia, a loose confederation of organised crime networks, grew in influence in the late 19th century. The Fascist regime began suppressing them in the 1920s with huge success, although the Mafia regained power in the aftermath of World War II.[20]

The Southern Question

Many academics, politicians and other influential people have contributed to "Meridionalism" (meridionalismo), opinions, and research, analysis and policy proposals regarding the south of Italy. Historically concentrating only on the economic gap between the north and south of Italy, the southern problem is now seen in the broader context of Europe.

The historian Pasquale Villari (1827–1917), the politician Sidney Sonnino (1847–1922) and the publicist Leopoldo Franchetti ( 1847–1917) were among the first to study in depth the effect of annexation to the Kingdom of Italy. To some of them, the unification was a form of military and economic colonialism. The early Meridionalists, although conservative, did not hesitate to reveal the serious responsibility of the government and the ruling classes, especially landowners.[25]

The solutions the Meridionalists proposed varied considerably due to their different viewpoints and political affiliations. For example, the writer and politician Napoleone Colajanni (1847–1921), a positivist and socialist, supported state intervention in the south as the only way to develop the area.[26] On the other hand, Antonio De Viti De Marco (1858–1943), a liberal economist and radical deputy, accepted state regulation of "natural" monopolies, but believed in free trade and was hostile to state interventionism.[27]

Francesco Saverio Nitti, (1868–1953) was an economist and political figure. A Radical, he served as the prime minister of Italy between 1919 and 1920. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia ("Theories of Overpopulation"), Nitti (Population and the Social System, 1894) was a staunch critic of English economist Thomas Robert Malthus and his Principle of Population.

Gaetano Salvemini graduated in literature in Florence in 1896. He taught History at the universities of Messina (during the 1908 Messina earthquake he was the only survivor of his entire family), Pisa and Florence. From 1919 to 1921 he served in Italian Parliament. As member of the Italian Socialist Party he fought for Universal Suffrage for the moral and economic rebirth of Italy's Mezzogiorno (southern Italy), and against corruption in politics.

Don Luigi Sturzo (1871–1959) was a Catholic priest and politician. Known in his lifetime as a "clerical socialist,"[28] Sturzo is considered one of the fathers of Christian democracy.[29] Sturzo was one of the founders of the Partito Popular Italiano in 1919, but was forced into exile in 1924 with the rise of Italian fascism. In exile in London (and later New York), Sturzo published over 400 articles (published posthumously under the title Miscellanea Londinese) critical of fascism, and later the post-war Christian Democrats in Italy.

Fascism

In 1922 the Fascists led by Benito Mussolini took power. The Fascist state undertook a serious program to develop the south. Through organizations such as the Istituto per la Ricostruzione Industriale (Institute for Industrial Reconstruction) and Istituto Mobiliare Italiano, the government sponsored numerous public works projects in the most deprived areas of the country, gave employment to many people, and promoted trade and investment.

The government improved the ports of Naples, Bari and Taranto, built new roads and railways, drained swamps and marshes, created canals and aqueducts in areas such as the Tavoliere delle Puglie, rationalized and mechanized the grape and olive agricultural enterprises in Sicily. After the Wall Street crash, the Fascist government further increased its financial commitment in the south, founding new factories (particularly for war production industries), purchased agricultural machinery and doubled the size of the civil service. Colonial wars in Africa opened new markets and new lands for settlers, and the growth of the army provided a livelihood for many young people.[30]

The Fascists seriously sought to eradicate the Mafia. Benito Mussolini launched a war without quarter against organized crime, often personally leading the operations. To do so he used harsh methods including torture, mass executions and special laws. He appointed Cesare Mori, called the "iron prefect" for his brutal methods, to the post of prefect of Palermo with extraordinary powers over the whole island. However, the Mafia was eradicated and only the top bosses survived escaping outside Italy, but the conflict with the Fascists led the Mafia (radicated in New York and Chicago) to ally with the Anglo-Americans during the Second World War.[31][32]

World War II and Sicilian Independence Movement

The Committee for the Independence of Sicily (Comitato per l'Indipendenza della Sicilia, CIS) was founded in September 1942 during the struggle between the Italian/German Axis and the US/Russian/British Allies.

The Allied forces successfully invaded Sicily in July 1943, and in general were warmly embraced by the Sicilian population influenced by Mafia gangster like Lucky Luciano.[20]

The CIS gained authority following the Armistice of Cassibile of 8 September 1943. In the spring of 1944, the CIS was disbanded and the Sicilian Independence Movement (Movimento Indipendentista Siciliano, MIS) was founded. Although the Allies prohibited any kind of political activity, they tolerated the existence of the MIS.

Italy became a Republic in 1946 and as part of the Constitution of Italy, Sicily was one of the five regions given special status as an autonomous region.[33] Both the partial Italian land reform and special funding from the Italian government's Cassa per il Mezzogiorno (Fund for the South) from 1950 to 1984, helped the Sicilian economy improve.[34][35]

However, the MIS remained active after the war.[36] One of the best-known members was Salvatore Giuliano, who formed a band variously described as freedom fighters or bandits, evading capture until he was killed in 1950.[37] Another early supporter was Calogero Vizzini, one of the most influential and legendary Mafia bosses of Sicily after World War II until his death in 1954, but Vizzini later shifted alliance to the Christian Democrat party.[38]

The political arm of the movement today calls itself the Sicilian National Front, (Italian: Fronte Nazionale Siciliano, Sicilian: Frunti Nazziunali Sicilianu) and is a socialist political party founded in 1964. Its Secretary General since 1976 is Giuseppe Naics. The movement is no longer a significant force. In the regional elections of 2006 the party obtained 679 votes in Palermo, or 0.2% of the vote.[39]

Current parties and groups

There continue to be various political parties and organizations who lobby for greater autonomy in the South, but they no longer claim widespread support.

Movement for the Autonomies

The Movement for the Autonomies (Movimento per le Autonomie, MpA) is a minor centrist regionalist political party in Italy. It demands economic development and greater autonomy primarily for Sicily, but also for other regions of Southern Italy. The party is led by Raffaele Lombardo, President of Sicily. In the 2008 general election, the party won 1.1% of the vote (7.4% in Sicily) and obtained 8 deputies and 2 senators through an alliance with The People of Freedom and Lega Nord parties. After the election the MpA joined the Berlusconi coalition.[40]

Sicilian Alliance

The Sicilian Alliance (Alleanza Siciliana) is a minor autonomist and national-conservative political party in Sicily, Italy. It was founded in 2005 and was led by Nello Musumeci, a MEP who was elected on the National Alliance's list. On 7 October 2007, the party joined to Francesco Storace's The Right, although maintaining some of its autonomy as a regional section of the party, named the "Sicilian Alliance – The Right", often shortened as "The Sicilian Right".[41]

Neo-Bourbon Cultural Association

The Associazione culturale Neoborbonica, or Neo-Bourbon Cultural Association is dedicated to restoring the history of the Bourbon kingdom, its glory, art, culture and identity, which they consider to have been maliciously falsified by the Piedmontese invaders. They aim to reconstruct the historical memory of the Two Sicilies, reconstruct their pride in being Southern Italian, and work towards the salvation of this ancient nation.[42] Passions are still high. When Prince Victor Emmanuel, head of the House of Savoy, returned to Italy in 2003 after a long exile he met hostility from both the neo-fascist Italian Social Movement and the Neo-Bourbon Movement in Naples in the form of posters, stickers and demonstrations.[43]

Two Sicilies Cultural Association

The Associazione Culturale Due Sicilie, or Two Sicilies Cultural Association is a website / blog that publishes commentary on the news as it affects the south of Italy. It is highly critical of government treatment of the south, and describes itself as a forum for discussing independence. It supports a Bourbon restoration on the grounds that a monarch would be more impartial than current politicians.[44]

Land and Liberation

Land and Liberation, or Terra e Liberazione is a pressure group founded in 1984 by a branch of the FNS that supports continued autonomy of Sicily with independent development of the economy. The group is politically far to the left, but has recently joined the Movement for Autonomy.[45]

Research Institutes

Several specialized research institutes today study the southern Italian economy in an attempt to better understand the problem and develop well-targeted economic policies. These include the Associazione nazionale per gli interessi del Mezzogiorno d'Italia (ANIMO) based in Rome,[46] the Associazione per lo sviluppo dell'industria nel Mezzogiorno (SVIMEZ) also based in Rome,[47] and the Associazione Studi e Ricerche per il Mezzogiorno (SRM) based in Naples.[48]

See also

Regionalist and independentist political parties

- For the South

- I the South

- Lega Sud Ausonia

- New Sicily

- Pact for Sicily

- Southern Action League

- Southern Democratic Party

- Social Christian Sicilian Union

Italian language Wikipedia

- Questione meridionale: article on the "Southern Question"

- Meridionalismo: article on "Meridionalism"

- Indipendentismo siciliano: article on "Sicilian independentism"

References

- ↑ L'indipendenza delle regioni - Demos & Pi

- ↑ Focus: La questione identitaria e indipendentista in Sardegna - UniCa, Ilenia Ruggiu

- 1 2 Smith, Dennis Mack (1997). Modern Italy; A Political History. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. pp. 95–96. ISBN 0-300-04342-2.

- ↑ Edward Gibbon, History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire Vol. IV, Chapters 41 & 43

- ↑ Wickham, Christopher (1998). "Aristocratic Power in Eighth-Century Lombard Italy". In Goffart, Walter A.; Murray, Alexander C. After Rome's Fall: Narrators and Sources of Early Medieval History, Essays presented to Walter Goffart. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 153–170. ISBN 0-8020-0779-1.

- ↑ McKitterick, Rosamond (1983). The Frankish Kingdoms under the Carolingians, 751–987. London: Longman. ISBN 0-582-49005-7.

- ↑ Smith, Denis Mack (1968). A History of Sicily: Medieval Sicily 800—1713. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 0-7011-1347-2.

- ↑ Norwich, John Julius (1967). The Normans in the South 1016–1130. London: Longmans. ISBN 0-14-015212-1.

- ↑ John Julius, Norwich. The Normans in Sicily: The Normans in the South 1016–1130 and the Kingdom in the Sun 1130–1194. Penguin Global. ISBN 978-0-14-015212-8.

- ↑ Colletta, Pietro (1858). History of the Kingdom of Naples (1858). University of Michigan.

- ↑ Tom Musco. "A History of Sicilian Cuisine". Retrieved 2009-04-14.

- ↑ "Arba Sicula". Arba Sicula. Retrieved 2009-04-14.

- ↑ François Mignet (1824). "History of the French Revolution from 1789 to 1814".

- ↑ Jeff Matthews. "Around Naples Encyclopedia". Retrieved 2009-04-18.

- ↑ "FERDINAND I, king of the Two Sicilies". New York: Columbia University Press. 2007. Retrieved 2009-04-18.

- ↑ "Ferdinand IV of Naples". 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2009-04-18.

- ↑ Correnti, Santi (2002). A Short History of Sicily. Montreal: Les Éditions Musae. ISBN 2-922621-00-6.

- ↑ Holt, Edgar (1971). The Making of Italy 1815–1870.

- ↑ "Italy". The English Mail. 1866-10-05. Retrieved 2009-04-18.

- 1 2 3 "Italians around the World: Teaching Italian Migration from a Transnational Perspective". OAH.org. 7 October 2007.

- ↑ "Sicily". Capitol Hill. 7 October 2007. Archived from the original on October 18, 2007.

- ↑ "fascio siciliano". Encyclopædia Britannica. 7 October 2007.

- ↑ John Dickie (1999-11-01). Darkest Italy: The Nation and Stereotypes of the Mezzogiorno, 1860–1900. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-22168-3.

- ↑ Clark, Martin (1984). Modern Italy: 1871–1982. London and New York: Longman Group UK Limited. pp. 16–18. ISBN 0-582-48361-1.

- ↑ Nelson Moe (July 2002). "The View from Vesuvius: Italian Culture and the Southern Question". University of California. Retrieved 2009-04-18.

- ↑ "Napoleone Colajanni". LoveToKnow 1911. Retrieved 2009-04-18.

- ↑ Mosca, Manuela (2004). "The notion of market power in the Italian marginalist school De Viti de Marco and Pantaleoni". Servizi Informatici Bibliotecari di Ateneo: Università degli Studi di Lecce. Retrieved 2009-04-18.

- ↑ Living Age. 1922, May 13. "Clerical Socialist." Vol. 313, p. 374.

- ↑ Moos, Malcolm (1945). Don Luigi Sturzo--Christian Democrat. The American Political Science Review. pp. 269–292.

- ↑ Jeffrey Herbener (2005-10-13). "The Vampire Economy: Italy, Germany, and the US". Mises Institute. Retrieved 2009-04-18.

- ↑ Selwyn Raab (2005). Five Families: The Rise, Decline, and Resurgence of America's Most Powerful Mafia Empires. Thomas Dunne. ISBN 978-0-312-30094-4.

- ↑ John Dickie (2007). Cosa Nostra: A History of the Sicilian Mafia. Hodder. p. 176. ISBN 1-4039-7042-4.

- ↑ "Sicily autonomy". Grifasi-Sicilia.com. 7 October 2007.

- ↑ "Italy - Land Reforms". Encyclopædia Britannica. 7 October 2007.

- ↑ "North and South: The Tragedy of Equalization in Italy" (PDF). Frontier Center for Public Policy. 7 October 2007.

- ↑ "Movimento per l'Indipendenza della Sicilia website". Movimento per l'Indipendenza della Sicilia. Retrieved 2009-04-14.

- ↑ "Bandit's End". Time Magazine. 1950-07-17. Retrieved 2009-04-15.

- ↑ Judith Chubb (1989). "The Mafia and Politics: The Italian State Under Siege". Cornell Studies in International Affairs. Retrieved 2009-04-15.

- ↑ "Movimento per L'Indipendenza Della Sicilia". Retrieved 2009-04-15.

- ↑ "Lombardo si allea con Storace "Intesa per superare il 4%"". Corriere della Sera. 2009-04-03. Retrieved 2009-04-14.

- ↑ "La Destra - Alleanza Siciliana". Alleanza Siciliana. Retrieved 2009-04-14.

- ↑ "Associazione culturale Neoborbonica". Retrieved 2009-04-14.

- ↑ Bruce Johnston (2003-03-18). "Italy's exiled royal family shunned as they return". Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 2009-04-15.

- ↑ "Associazione Culturale Due Sicilie". Retrieved 2009-04-14.

- ↑ "Terra e Liberazione". Retrieved 2009-04-14.

- ↑ "ANIMO Home Page". Associazione nazionale per gli interessi del Mezzogiorno d'Italia. Retrieved 2009-04-17.

- ↑ "SVIMEZ Home Page". Associazione per lo sviluppo dell'industria nel Mezzogiorno. Retrieved 2009-04-17.

- ↑ "SRM - Associazione Studi e Ricerche per il Mezzogiorno Home Page". Associazione Studi e Ricerche per il Mezzogiorno. Retrieved 2009-04-17.