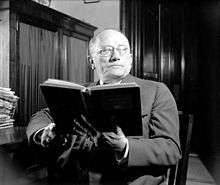

Theodore G. Bilbo

| Theodore G. Bilbo | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from Mississippi | |

|

In office January 3, 1935 – August 21, 1947 | |

| Preceded by | Hubert D. Stephens |

| Succeeded by | John C. Stennis |

| 43rd Governor of Mississippi | |

|

In office January 16, 1928 – January 19, 1932 | |

| Lieutenant | Cayton B. Adam |

| Preceded by | Dennis Murphree |

| Succeeded by | Martin Sennett Conner |

| 39th Governor of Mississippi | |

|

In office January 18, 1916 – January 18, 1920 | |

| Lieutenant | Lee M. Russell |

| Preceded by | Earl L. Brewer |

| Succeeded by | Lee M. Russell |

| 11th Lieutenant Governor of Mississippi | |

|

In office January 16, 1912 – January 18, 1916 | |

| Governor | Earl L. Brewer |

| Preceded by | Luther Manship |

| Succeeded by | Lee M. Russell |

| Member of the Mississippi Senate | |

|

In office 1908–1912 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Theodore Gilmore Bilbo October 13, 1877 Pearl River County, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Died |

August 21, 1947 (aged 69) New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Resting place | Juniper Grove Cemetery, Poplarville, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) |

(1) Lillian Selita Herrington (1898–1899, died) (2) Lida Ruth Gaddy[1] |

| Education | |

| Religion | Baptist; Freemason[2] |

Theodore Gilmore Bilbo (October 13, 1877 – August 21, 1947) was an American politician. Bilbo, a Democrat, twice served as governor of Mississippi (1916–20, 1928–32) and later was elected a U.S. Senator (1935–47). A master of filibuster and scathing rhetoric, a rough-and-tumble fighter in debate, he made his name a synonym for white supremacy. Like many Southern Democrats, Bilbo believed that black people were inferior; he defended segregation, and was a member of the Ku Klux Klan.[3][4]

Bilbo was educated in rural Hancock County (later Pearl River County). He attended Peabody Normal College in Nashville, Tennessee and Vanderbilt University Law School. After teaching school he attained admission to the bar in 1906, and practiced in Poplarville. A Democrat, he served in the Mississippi State Senate for four years, 1908 to 1912. He overcame accusations of accepting bribes and won election as lieutenant governor, a position he held from 1912 to 1916.

In 1915, Bilbo won election as governor, and he served from 1916 to 1920. During this term he earned accolades for enacting Progressive measures such as compulsory school attendance, as well as increased spending on public works projects. He was an unsuccessful candidate for the United States House of Representatives in 1920.

Bilbo won election to the governorship again in 1927, and served from 1928 to 1932. During this term Bilbo caused controversy by attempting to move the University of Mississippi from Oxford to Jackson. In another controversy, he aided Democratic nominee Al Smith in the 1928 presidential election by spreading the story that Republican nominee Herbert Hoover had socialized with a black woman; Southern voters, considering whether to maintain their allegiance to the Democratic Party in light of Smith's Catholicism and support for the repeal of Prohibition largely remained with Smith after Bilbo's appeal to racism.

In 1934 Bilbo won election to a seat in the United States Senate; he served from 1935 until his death. In the Senate, Bilbo maintained his support for segregation and white supremacy; he was also attracted to the ideas of the black separatist movement, considering it a potentially viable method of maintaining segregation. He died in a New Orleans hospital while undergoing treatment for cancer, and was buried at Juniper Grove Cemetery in Poplarville.

Bilbo was of short stature (5 ft 2 in or 1.57 m); he frequently wore bright, flashy clothing to draw attention to himself, and he was nicknamed "The Man" because he tended to refer to himself in the third person.[5]

Bilbo was the author of a pro-segregation work, Take Your Choice: Separation or Mongrelization.[6]

Education and family background

On October 13, 1877, Bilbo was born in the small town of Juniper Grove in Hancock (later Pearl River) County.[7] His parents, Obedience "Beedy" (née Wallis or Wallace) and James Oliver Bilbo were of Scotch-Irish descent, and James was a farmer and veteran of the Confederate States Army who rose from poverty during Theodore Bilbo's early years to become Vice President of the Poplarville National Bank.[7][8] Theodore Bilbo obtained a scholarship to attend Peabody Normal College in Nashville, Tennessee,[7] and later attended Vanderbilt University Law School, but did not graduate from either.[9] He also taught school and worked at a drug store during his legal studies,[10] was admitted to the bar in Tennessee in 1906, and began a law practice in Poplarville, Mississippi the following year.[1]

During his teaching career, Bilbo was accused of being overly familiar with a female student.[11] At Vanderbilt, though he had been admitted to the senior class, he left without graduating. He was accused of cheating on academics, but it appears more likely that he left school for financial reasons.[12] Though these accusations never rose to the level of formal charges, they helped create the perception that Bilbo was profligate and dishonest.[13]

State Senate

On November 5, 1907, Bilbo was elected to the Mississippi State Senate.[1] He served there from 1908 to 1912.

In 1909 he attended non-credit summer courses at the University of Michigan Law School during a period when the legislature was not in session.[14][15]

In 1910, Bilbo attracted national attention in a bribery scandal. After the death of U.S. Senator James Gordon, the legislature was deadlocked in choosing between LeRoy Percy or former Governor James K. Vardaman as Gordon's successor. After 58 ballots, on February 28 Bilbo was one of several candidates to break the stalemate by switching his vote to Percy, who won 87–82.[16] Bilbo told a grand jury the next day that he had accepted a 645 dollar bribe from L.C. Dulaney, but that he had done so as part of a private investigation.[17] The State Senate voted 28–10 to expel him from office, falling one vote short of the 3/4 majority needed.[18] The Senate passed a resolution calling him "unfit to sit with honest, upright men in a respectable legislative body."[19]

During his subsequent campaign for lieutenant governor, Bilbo made a comment to Washington Dorsey Gibbs, a state senator from Yazoo City.[20] Gibbs was insulted, and during the ensuing skirmish broke his cane over Bilbo's head. But Bilbo's campaign was successful, and he served as lieutenant governor from 1912 to 1916. One of his first acts as lieutenant governor was to remove from the records the resolution calling him "unfit to sit with honest men."

Governorship

After serving as Lieutenant Governor of Mississippi for four years, Bilbo was elected governor in 1915. Cresswell (2006) argues that in his first term (1916–20) Bilbo had "the most successful administration" of all the governors who served between 1877 and 1917, putting state finances in order and supporting Progressive measures such as compulsory school attendance, a new charity hospital, and a board of bank examiners.[21]

In his first term, his Progressive program was largely implemented. He was known as "Bilbo the Builder" because of his authorization of a state highway system, as well as lime-crushing plants, new dormitories at the Old Soldiers' Home, and a tuberculosis hospital. He pushed through a law eliminating public hangings and worked on eradication of the South American tick. The state constitution prohibited governors from having successive terms.

Bilbo chose to run for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1920. During the campaign, a bout of "Texas fever" broke out, and Bilbo supported a program to dip cattle in insecticide to kill the ticks carrying the fever. Mississippi farmers were generally not happy about the idea, and Bilbo was unable to win a seat.

Afterward, Bilbo caused controversy by hiding in a barn to avoid a subpoena in a case involving his friend, then-governor Lee M. Russell.[22] He had served as Bilbo's lieutenant governor, and was being sued by his former secretary, who accused Russell of breach of promise and of seducing and impregnating her. She had undergone an abortion that left her unable to have children.

Russell asked Bilbo to try to convince the secretary not to sue him. In this, Russell was unsuccessful, but his accuser was unsuccessful as well in her suit against him. Judge Edwin R. Holmes sentenced Bilbo to 30 days in prison for "contempt of court," and he served 10 days behind bars. He lost his run for re-election in 1923.

In 1927, Bilbo was elected governor again after winning the Democratic primary in a runoff election over Governor Dennis Murphree, who had succeeded to the top position from the lieutenant governorship on the death of Governor Henry L. Whitfield.

The lieutenant governor in Bilbo's last term as governor was the lawyer Bidwell Adam, a strong party loyalist and a staunch segregationist from Pass Christian and later Gulfport, sometimes known as the "firebrand from the Coast".[23]

Bilbo criticized Murphree for calling out the National Guard to prevent a lynching in Jackson, declaring that no black person was worthy of protection by the Guard.[24]

His second term was filled with controversy involving his plan to move the University of Mississippi from Oxford to Jackson. That idea was eventually defeated. During the 1928 presidential election, Bilbo helped Al Smith to carry the state by a large margin; he spread stories that Republican Herbert Hoover had socialized with a black woman, so voters should vote against him.

Firing the professors

In 1930, Bilbo convened a meeting of the State Board of Universities and Colleges to approve his plans to dismiss 179 faculty members. Appearing before reporters after the meeting, he announced, "Boys, we've just hung up a new record. We've bounced three college presidents and made three new ones in the record time of two hours. And that's just the beginning of what's going to happen."[25] The presidents of the University of Mississippi ("Ole Miss"), Mississippi A & M (later Mississippi State University), and the Mississippi State College for Women were all fired and replaced, respectively, by a realtor, a press agent, and a recent B.A. degree-recipient.[25] The Dean of the Medical School at Ole Miss was replaced by "a man who once had a course in dentistry."[25]

The Association of American Universities and the Southern Association of College and Secondary Schools suspended recognition of degrees from all four of Mississippi's state colleges. The American Medical Association voted to cancel the accreditation of the state's college of medicine.[26] The Association of American University Professors (AAUP), meeting in Cleveland, passed a resolution that the remaining Mississippi professors would "be regarded as retired members of the profession," after finding that the dismissals of employees had been made "for political considerations and without concern for the welfare of the students."[27] During the crisis, Bilbo was burned in effigy by students at Ole Miss, but he was unconcerned about the state's image. He made national headlines by giving an interview while "sitting in a tub of hot water, soap in one hand, washrag in the other, and a cigar in his mouth."[28] The lack of recognition continued until "satisfactory evidence of improved conditions" was provided to the AAUP and the other institutions in 1932.[29]

In his final year of office, Bilbo and the legislature were at a stalemate, when he refused to sign the tax bills, and the legislature refused to approve his bills. At the end of his term, the State of Mississippi was broke. The state treasury had only $1,326.57 in its coffers, and the state was $11.5 million in debt.[24] Bilbo, whose actions had halted U.S. Department of Agriculture funding of the agricultural school at Mississippi State, was hired as a "consultant on public relations" for the USDA for a short time. He clipped newspaper articles for a high salary, a reward from Senator Pat Harrison for Bilbo's campaign support. Pundits dubbed him the "Pastemaster General."[22] Soon, Bilbo made plans to run for the U.S. Senate seat held by Hubert Stephens.

U.S. Senate

In 1934, Bilbo defeated Stephens to win a seat in the United States Senate. There he spoke against "farmer murderers," "poor-folks haters," "shooters of widows and orphans," "international well-poisoners," "charity hospital destroyers," "spitters on our heroic veterans," "rich enemies of our public schools," "private bankers 'who ought to come out in the open and let folks see what they're doing'," "European debt-cancelers," "unemployment makers," pacifists, Communists, munitions manufacturers, and "skunks who steal Gideon Bibles from hotel rooms."[24]

In Washington, Bilbo feuded with Mississippi senior Senator Pat Harrison. Bilbo, whose base was among tenant farmers, hated the upper-class Harrison, who represented the rich planters and merchants. The feud started in 1936 when Harrison nominated Judge Holmes for the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. Bilbo disliked Holmes, dating back to the Russell case, and spoke against him for five hours. Bilbo was the only Senator to vote "no," and Holmes was confirmed.

Later that year, Harrison faced a primary challenge from former Governor Mike Conner. Bilbo supported Conner. Bilbo's former law partner Stewart C. "Sweep Clean" Broom, campaigned for Harrison.[30] Harrison won reelection.

When the Senate majority leader’s job opened up in 1937, Harrison ran and faced a close contest with Kentucky’s Alben Barkley. Harrison’s campaign manager asked Bilbo to consider voting for Harrison. Bilbo said he would vote for Harrison only if Harrison asked him personally. When asked if he would make the personal appeal to Bilbo, Harrison replied, "Tell the son of a bitch I wouldn’t speak to him even if it meant the presidency of the United States."[31] Harrison lost by one vote, 37-to-38, and his reputation as the Senator who wouldn’t speak to his home-state colleague remained intact. Bilbo had taken revenge by voting against his fellow Mississippian.

In the Senate, Bilbo supported Democratic President Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal. Bilbo's outspoken support of segregation and white supremacy was controversial in the Senate. Attracted by the ideas of black separatists such as Marcus Garvey, Bilbo proposed an amendment to the federal work-relief bill on June 6, 1938, which would have deported 12 million black Americans to Liberia at federal expense to relieve unemployment.[32] He wrote a book advocating the idea. Garvey praised him in return, saying that Bilbo had "done wonderfully well for the Negro."[33] But Thomas W. Harvey, a senior Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League leader in the US, distanced himself from Bilbo because of his racist speeches.[34]

The Democrats assigned Bilbo to what was considered the least important Senate committee, one on governance of the District of Columbia, to try to limit his influence. He used his position to advance his white supremacist views. Bilbo was against giving any vote to district residents, especially as the district's black population was increasing during the Great Migration. After re-election, he advanced to sufficient seniority to chair the committee, 1945–47. He also served on the Pensions Committee, chairing it 1942–45.[35]

Bilbo revealed his membership in the Ku Klux Klan in an interview on the radio program Meet the Press. He said, "No man can leave the Klan. He takes an oath not to do that. Once a Ku Klux, always a Ku Klux."[36]

Bilbo was outspoken in saying that blacks should not be allowed to vote anywhere in the United States, regardless of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments to the Constitution. Black World War II veterans complained of longstanding disfranchisement in the South, which Mississippi had achieved in 1890 by changes to its constitution related to electoral and voter registration rules. (Other Southern states followed with similar changes through 1910, which survived most court challenges.) Bilbo's campaign was accused of provoking violence related to voting. Critics accused Bilbo of giving war contracts out to his friends.

He was a prominent participant in the lengthy southern Democratic filibuster of the Costigan-Walker anti-lynching bill before the Senate in 1938. Bilbo said:

If you succeed in the passage of this bill, you will open the floodgates of hell in the South. Raping, mobbing, lynching, race riots, and crime will be increased a thousandfold; and upon your garments and the garments of those who are responsible for the passage of the measure will be the blood of the raped and outraged daughters of Dixie, as well as the blood of the perpetrators of these crimes that the red-blooded Anglo-Saxon White Southern men will not tolerate.[36]

Bilbo denounced Richard Wright's autobiography, Black Boy, on the Senate floor:

Its purpose is to plant the seeds of devilment and trouble-breeding in the days to come in the mind and heart of every American Negro.... It is the dirtiest, filthiest, lousiest, most obscene piece of writing that I have ever seen in print. I would hate to have a son or daughter of mine permitted to read it; it is so filthy and so dirty. But it comes from a Negro, and you cannot expect any better from a person of his type.[37]

During the 1946 Democratic Senate primary in Mississippi, his last race, Bilbo was the subject of a series of attacks by famed journalist Hodding Carter, Jr., in his paper, the Greenville Delta Democrat-Times. He won that primary against three other opponents with 51.0 percent of the vote; one of his rivals was Nelson Trimble Levings, who owned a Mississippi plantation and was an investment banker in New York City. As usual, Bilbo faced no Republican opposition in the 1946 general election. Based on a request by liberal Democratic Senator Glen H. Taylor of Idaho, the newly elected Republican majority in the United States Senate refused to seat Bilbo for the term to which he was elected because of his speeches. He was believed to have incited violence against blacks who wanted to vote in the South. In addition, a committee found that he had taken bribes. A filibuster by his supporters delayed the seating of the Senate for days. It was resolved when a supporter proposed that Bilbo's credentials remain on the table while he returned home to Mississippi to seek medical treatment for oral cancer.[38][39]

Death

Bilbo retired to his "Dream House" estate in Poplarville, Mississippi, where he wrote and published a summary of his racial ideas entitled Take Your Choice: Separation or Mongrelization (Dream House Publishing Company, 1947). His house, which served as the namesake and office of his publishing company, burned down in late fall that year, with the fire consuming many copies of the book.

Bilbo died at the age of 69 in New Orleans, Louisiana. On his deathbed he summoned Leon Louis, the editor of the black newspaper Negro South to make a statement:

I am honestly against the social intermingling of Negroes and Whites but I hold nothing personal against the Negroes as a race. They should be proud of their God-given heritage just as I am proud of mine. I believe Negroes should have the right [to indiscriminate use of the ballot], and in Mississippi too—when their main purpose is not to put me out of office and when they won't try to besmirch the reputation of my state.[40]

Bilbo was treated at the forerunner of New Orleans' Ochsner Medical Center called Ochsner Clinic. An orderly named Frank Wilderson, an African-American student at Xavier University (later a vice president at the University of Minnesota),[41] worked part-time at the Oschner Clinic at the time. After Bilbo died, the orderlies on duty left Bilbo's body in the room until Wilderson began work later that night, so that the African-American orderly could remove the body of the segregationist. Wilderson said in a 2004 newspaper article, "the moment was stark because alive he [Bilbo] would have resisted any attempt for me to touch him."[42][43]

His funeral at Juniper Grove Cemetery[44] in Poplarville was attended by five thousand mourners, including the governor and the junior senator. A bronze statue of Bilbo was placed in the rotunda of the Mississippi State Capitol building. It was relocated to another room, which is now frequently used by the Legislative Black Caucus. Some of the members use the statue's outstretched arm as a coat rack.[45]

In popular culture

Bilbo was satirized multiple times in popular culture.

- In 1946 he was the subject of Bob and Adrienne Claiborne's song, "Listen Mr. Bilbo" (1946);[46]

- Jack Webb devoted an episode of his crusading 1946 radio show One Out of Seven to attacking Bilbo's racial views. He dramatized extracts from Bilbo's speeches and letters attacking Negroes, "Dagoes" (Italians), and Jews, while asserting after each extract some variation of "...but Senator Bilbo is an honorable man. We do not intend to prove otherwise." (John Dunning, the author of On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio, says this was a deliberate reference to Marc Antony's funeral oration in Shakespeare's play Julius Caesar).[47]

- In 1947 he was the subject of blues song "Bilbo is Dead"[48] by Andrew Tibbs.

- He was also mentioned in the 1947 Gregory Peck film Gentleman's Agreement as an examplar of bigotry.

Books

- Take Your Choice: Separation or Mongrelization by Theodore G. Bilbo (1946). A compendium of segregationist arguments.

References

- 1 2 3 Rowland, Dunbar, ed. (1908). "Sketches of State Senators and Representatives". The Official and Statistical Register of the State of Mississippi (PDF). Nashville, Tennessee: Brandon Printing Company. pp. 998–999. Retrieved 20 Mar 2014.

- ↑ Lawrence Kestenbaum. "Index to Politicians: Bilandic to Billinghurst". The Political Graveyard. Retrieved 2016-08-10.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-01-22. Retrieved 2011-10-26.

- ↑ "Sen. Theodore G. Bilbo's Legacy of Hate | Common Dreams | Breaking News & Views for the Progressive Community". Common Dreams. 2007-07-17. Retrieved 2016-08-10.

- ↑ Current Biography 1943, pp. 47–50.

- ↑ "Full text of "Take Your Choice: Separation or Mongrelization"". Archive.org. Retrieved 2016-08-10.

- 1 2 3 Rowland, Dunbar (1908). The Official and Statistical Register of the State of Mississippi, Volume 2. Nashville, TN: Brandon Printing Company. pp. 998–999.

- ↑ Cutter, William Richard (1931). American Biography: A New Cyclopedia, Volume 46. New York, NY: American Historical Society. p. 10.

- ↑ Ryan, James Gilbert; Schlup, Leonard C. (2006). Historical Dictionary of the 1940s. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, Inc. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-7656-0440-8.

- ↑ Morgan, Chester M. (1985). Redneck Liberal: Theodore G. Bilbo and the New Deal. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press. pp. 27–28. ISBN 978-0-8071-2432-1.

- ↑ Hamilton, Charles Granville (1978). Progressive Mississippi. Jackson, MS: Charles G. Hamilton. p. 153.

- ↑ Mississippi State Senate (1910). Investigation by the Senate of the State of Mississippi of the Charges of Bribery in the Election of a United States Senator. Nashville, TN: Brandon Printing Company. pp. 93–94.

- ↑ Morgan, Chester M. (1985). Redneck Liberal: Theodore G. Bilbo and the New Deal. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-8071-2432-1.

- ↑ Chester M. Morgan, Redneck Liberal: Theodore G. Bilbo and the New Deal, 1985, page 31

- ↑ Larry Thomas Balsamo, Theodore G. Bilbo and Mississippi politics, 1877-1932, 1967, page 36

- ↑ "Vardaman Defeated," Fort Wayne News, February 23, 1910, p2

- ↑ "Mississippi Senate Takes Up Bilbo's Bribery Charge," Indianapolis Star, March 30, 1910, p2

- ↑ "Senator Bilbo Narrowly Escapes From Expulsion," The Anaconda Standard, April 15, 1910, p1

- ↑ Morgan, Chester. Redneck Liberal: Theodore G. Bilbo and the New Deal, pg. 33

- ↑ "Washington Dorsey Gibbs", from The Official and Statistical Register of the State of Mississippi. From Google Books. Retrieved February 23, 2013.

- ↑ Cresswell (2006) pp. 212—13

- 1 2 "Southern Statesman" Time (magazine), October 01, 1934.

- ↑ Billy Hathorn, "Challenging the Status Quo: Rubel Lex Phillips and the Mississippi Republican Party (1963-1967)", The Journal of Mississippi History XLVII, November 1985, No. 4, p. 255

- 1 2 3 Current Biography 1943, p49

- 1 2 3 The New Republic, September 17, 1930, quoted in the Decatur Evening Herald, 9/16/30 p6

- ↑ "Four Schools Facing Ouster," Salt Lake Tribune, December 29, 1930, p6

- ↑ "Educators Put Four Miss. Colleges on their Blacklist," The Clearfield Progress, December 30, 1930, p12

- ↑ AP Report, "Governor Bilbo Is Interviewed In His Bathtub," The Bee (Danville, Va.), December 20, 1930, p3

- ↑ "The AAUP's Censure List". AAUP. Retrieved 2016-08-10.

- ↑ "Broom or Bilbo". Time. August 24, 1936.

- ↑ "Mississippi Spurning". U.S. News & World Report. 120: 122. 1996. Retrieved 2011-09-21.

- ↑ Current Biography 1943, p50

- ↑ Ibrahim K. Sundiata, Brothers and Strangers: Black Zion, Black Slavery, 1914-1940, Duke University Press 2003. ISBN 0-8223-3247-7, p. 313

- ↑ Michael W. Fitzgerald, "'We Have Found a Moses': Theodore Bilbo, Black Nationalism, and the Greater Liberia Bill of 1939", The Journal of Southern History Vol. 63, No. 2 (May, 1997), pp. 293-320 Published by: Southern Historical Association, p 301

- ↑ "CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES : [Table 5-3] 1789 - present" (PDF). Senate.gov. Retrieved 2016-08-10.

- 1 2 Robert L. Fleegler, "Theodore G. Bilbo and the Decline of Public Racism, 1938-1947", The Journal of Mississippi History, Spring 2006

- ↑ Pierre Tristam. "Theodore G. Bilbo on Richard Wright's "Black Boy" / Congressional Record, 1945 [Candide's Notebooks]". Pierretristam.com. Retrieved 2016-08-10.

- ↑ "1941: Member's Death Ends a Senate Predicament - August 21, 1947". Senate.gov. Retrieved 2016-08-10.

- ↑ "THE CONGRESS: That Man - Printout". TIME. 1947-01-13. Retrieved 2016-08-10.

- ↑ "He Died a Martyr", Time, September 1, 1947

- ↑ "SJU Names New Board of Regents Members â€" CSB/SJU". Csbsju.edu. 1997-05-05. Retrieved 2016-08-10.

- ↑ The News Examiner, March 18, 2004, pg. 2

- ↑ "The Italicized Life of Frank B. Wilderson III '78.", Dartmouthalumnimagazine.com. Retrieved February 23, 2013.

- ↑ "Theodore Gilmore Bilbo". Usgwarchives.net. 1947-08-21. Retrieved 2016-08-10.

- ↑ "South in new disputes over heritage". Washington Times. Retrieved 2016-08-10.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-10-15. Retrieved 2009-01-20.

- ↑ John Dunning. On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio. Books.google.com. p. 522. Retrieved 2016-08-10.

- ↑ "Bilbo Is Dead - Andrew Tibbs (1947)". YouTube. 1976-10-29. Retrieved 2016-08-10.

Further reading

- Boulard, Garry, "'The Man' vs. 'The Quisling': Theodore Bilbo, Hodding Carter and the 1946 Democratic Parimary," Journal of Mississippi History,1989, 51, 201-17.

- Cresswell, Stephen. Rednecks, Redeemers, And Race: Mississippi After Reconstruction, 1877-1917], 2006 - excerpt and text search]

- Gehrke, Pat J. "The Southern Association of Teachers of Speech v. Senator Theodore Bilbo: Restraint and Indirection as Rhetorical Strategies." Southern Communication Journal 2007, 72, 95-104.

- Giroux, Vincent A., Jr. "The Rise of Theodore G. Bilbo (1908–1932)," Journal of Mississippi History 1981 43(3): 180-209,

- Morgan, Chester M. Redneck Liberal: Theodore G. Bilbo and the New Deal, Louisiana State U. Press, 1985. 274 pp.

- United States Congress. "Theodore G. Bilbo (id: b000460)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Theodore G. Bilbo, Take Your Choice: Separation or Mongrelization, Internet Archive (PDF; 600 KB)

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Theodore G. Bilbo |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Theodore G. Bilbo. |

- Theodore G. Bilbo at Find a Grave

- "Robert L. Fleeger, "Theodore G. Bilbo and the Decline of Public Racism, 1938-1947"" (PDF)., Mississippi Department of Archives and History (76.8 KB). Details Senate efforts to prevent Bilbo from resuming his seat in 1947.

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Luther Manship |

Lieutenant Governor of Mississippi 1912–1916 |

Succeeded by Lee M. Russell |

| Preceded by Earl L. Brewer |

Governor of Mississippi 1916–1920 |

Succeeded by Lee M. Russell |

| Preceded by Dennis Murphree |

Governor of Mississippi 1928–1932 |

Succeeded by Martin Sennett Conner |

| United States Senate | ||

| Preceded by Hubert D. Stephens |

U.S. Senator (Class 1) from Mississippi 1935–1947 Served alongside: Pat Harrison, James O. Eastland, Wall Doxey |

Succeeded by John C. Stennis |

.svg.png)