The Kampung Boy

.jpg) The Kampung Boy (1979), first print | |

| Author | Lat |

|---|---|

| Country | Malaysia |

| Language | Malglish, a pidgin form of English |

| Genre | Autobiographical comics |

| Publisher | Berita Publishing |

Publication date | 1979 |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 144 pp (first edition) |

| OCLC | 5960451 |

| 741.59595 | |

| LC Class | PZ7.L3298 |

| Followed by | Town Boy |

The Kampung Boy, also known as Lat, the Kampung Boy or simply Kampung Boy, is a graphic novel by Lat about a young boy's experience growing up in rural Perak in the 1950s. The book is an autobiographical account of the artist's life, telling of his adventures in the jungles and tin mines, his circumcision, family, and school life. It is also the basis for the eponymous animated series broadcast in 1999. First published in 1979 by Berita Publishing, The Kampung Boy was a commercial and critical success; its first printing (of at least 60,000 copies, 16 times) was sold out within four months of its release. Narrated in English with a smattering of Malay, the work has been translated into other languages, such as Japanese and French, and sold abroad.

The book made Lat an international figure and a highly regarded cartoonist in Malaysia. It won several awards when released as Kampung Boy in the United States, such as Outstanding International Book for 2007 and the Children's Book Council and Booklist Editor's Choice for 2006. The Kampung Boy became a franchise, with the characters of The Kampung Boy decorating calendars, stamps, and aeroplanes. A Malaysian theme park is scheduled to open in 2012 with the fictional characters as part of its attractions. The Kampung Boy is very popular in Southeast Asia and has gone through 16 reprints. A sequel, Town Boy, which followed the protagonist in his teenage years in the city, was published in 1981 and a spin-off, Kampung Boy: Yesterday and Today, in 1993. The latter reused the setting of The Kampung Boy to compare and contrast the differences between Malaysian childhood experiences in the 1950s and 1980s.

Plot

The Kampung Boy tells the story of a young boy, Lat, and his childhood in a kampung (village). A graphic novel, it illustrates the boy's life in pictures and words. Aside from being the protagonist, Lat is also the narrator. The story opens with his birth in a kampung in Perak, Malaysia, and the traditional rituals surrounding the event: the recitation of blessings, the singing of religious songs, and the observance of ceremonies. As Lat grows older, he explores the house, gradually shifting the story's focus to the comic activities of his family outside their abode.[1]

Lat starts the first stage of his formal education—reading the Qur'an. At these religious classes, he makes new friends and joins them in their adventures, swimming in the rivers and exploring the jungles. Lat's parents worry over his lack of interest in his studies; he acknowledges their concern but finds himself unmotivated to forgo play for academic pursuits. When he reaches his tenth year, he undergoes the bersunat, a ritual circumcision. The ceremonies that precede the operation are elaborate, with processions and baths in the river. The circumcision proves to be "just like an ant bite!"[2][3]

Sometime after recovering from the circumcision, Lat trespasses on a tin mine with his friends. They teach him how to gather the mud left in the wake of the mining dredges and pan for valuable ore. The activity is illegal but often overlooked by the miners. Lat brings the result of his labour back to his father, expecting praise. Instead, he is punished for neglecting his studies and future. After overhearing his parents' laments and being shown the family's rubber plantation, Lat finds the will to push himself to study. He is rewarded for his efforts, passing a "special examination" and qualifying for a "high-standard" boarding school in Ipoh, the state capital.[4]

Rushing home to inform his parents, Lat discovers his father in negotiations with a tin mining company, which is surveying the land. The company will offer a large sum of money for the family's properties if they discover tin on it. Other villagers are hoping for similar deals with the company. They plan to buy houses in Ipoh if their hopes are realised. The day for Lat to depart the village has arrived and he is excited, but as he is about to depart, sadness washes over him. He acknowledges the emotions as his love of the village and hopes that the place where he was born will remain unchanged when he returns and see it changed.[5]

Conception

The Kampung Boy is an autobiography. Its author, Lat, grew up in a kampung and moved to the city after graduating from high school. He worked there as a crime reporter and drew cartoons to supplement his income—a hobby he had started at the age of nine.[6] Lat became the column cartoonist for his newspaper after impressing his editors with his cartoons on the bersunat.[7][8] He was sent to London to study at St Martin's School of Art[9] and on returning to Malaysia in 1975, he reinvented his column, Scenes of Malaysian Life, into an editorial comic series.[10] It proved popular and as Lat's fame grew, he began questioning his city lifestyle and reminiscing about his life in the kampung. Lat felt he and his fellow citizens had all forgotten their village origins and wanted to remind them of that. He began working on The Kampung Boy in 1977, conceptualising and drawing the scenes when he was not drawing Scenes of Malaysian Life. His labour came to fruition in 1979 when Berita Publishing Sendirian Berhad released The Kampung Boy on the Malaysian market.[11]

Art style and presentation

The style of Kampung Boy does not follow that commonly found in Western graphic novels.[12] A page can be occupied fully by a single drawing, accompanied by text. The image either presents a scene that stands on its own or segues into the next, forming a story sequence that flows across two facing pages.[13] The story is told in a local dialect of English, simpler in its grammatical structure and sprinkled with Malay words and phrases.[14] Deborah Stevenson, editor of The Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books, found that the narration invokes a sense of camaraderie with the reader, and carries an "understated affection for family, neighbours and village life."[12] Mike Shuttleworth, reviewer for The Age, said that Lat often achieved humour in this book by illustrating the scene contrary to what was described.[15] Stevenson agreed, highlighting a scene in which Mat spoke of how his mother tenderly fed him porridge; the illustration, however, shows her irritation as the toddler spits the porridge back at her.[12]

Kevin Steinberger, reviewer for Magpies, found Lat's layout made Kampung Boy an "easy, inviting read." He said that Lat's pen-and-ink drawings relied on the "strong contrast between black and white to create space and suggest substance."[16] Lat drew the children of Kampung Boy as "mostly mop-topped, toothy, bare-bottomed or sarong-draped" kids,[2] who are often "exaggeratedly dwarfed" by items of the adult world.[12] He explained that the way the boys were drawn was partly due to the influence of comics he read in the 1950s; "naughty ones with ... bushy hair" were prominent male protagonists in those books.[17] The adult characters are easily distinguished by their exaggerated clothing and accessories such as puffed out pants and butterfly glasses.[2] "Short and round" shapes make the design of the characters distinctive.[18] These characters display exaggerated expressions, particularly when they are drawn to face the readers.[13]

Francisca Goldsmith, a librarian and comics reviewer, found Lat's scenes to be "scribbly", yet "wonderfully detailed".[2] Similarly, comics journalist Greg McElhatton commented that The Kampung Boy was "a strange mix of caricature and careful, fine detail."[13] These two views lend support to Muliyadi's assertion that Lat demonstrated his strength in The Kampung Boy; his eye for detail extended to his characters and, more importantly, the surroundings. Lat's characters look, dress, act, and talk like real Malaysians would, and they are placed in environments that are readily identifiable with local jungles, villages, and cities. The faithful details impart a sense of familiarity to Malaysian readers and make the scenes convincing to others.[19]

Adaptations

New Straits Times, the paper Lat was working for in the 1970s, was published in English; its directive was to serve a multi-racial readership. Redza commented that Lat understood Malaysian society and the need to engage all of its racial groups.[20] The Kampung Boy was thus written and published in English. At Lat's request, Berita Publishing hired his friend, Zainon Ahmad, to translate the graphic novel into Malay. This version was published under the title Budak Kampung.[21] By 2008, The Kampung Boy had been reprinted 16 times,[nb 1] and translated into various languages such as Portuguese, French, and Japanese. Countries that have printed localised versions of The Kampung Boy include Brazil,[22] Germany, Korea and the United States.[23]

United States adaptation

The United States adaptation, which dropped the definite article from the title, was published by First Second Books in 2006.[21] The book is in a smaller format (6 inches by 8 inches) and sported Matt Groening's testimonial—"one of the all-time great cartoon books"—on its cover.[24] According to Gina Gagliano, First Second's Marketing Associate, the publishers left the story mostly untouched; they had not altered the contents to be more befitting to American tastes. They did, however, change the grammar and spelling from British English (the standard followed by Malaysia) to the American version and lettered the text in a font based on Lat's handwriting.[25] First Second judged that the original book's sprinklings of Malay terms were not huge obstacles to their customers.[26] Most of the Malay words could be clearly understood from context, either through text or with the accompanying illustrations.[27] The clarity of the language left the publisher few terms to explain to North American readers; the few that remained were explained either by inserting definitions within parentheses or by replacing the Malay word with an English equivalent.[28]

Animated television series

The success of The Kampung Boy led to its adaptation as an animated series. Started in 1995, production took four years to complete and was an international effort, involving companies in countries such as Malaysia, the Philippines, and the United States.[29][30] The series uses the characters of the graphic novel, casting them in stories that bear similarities to The Simpsons. Comprising 26 episodes,[31] Kampung Boy features themes that focus on the meshing of traditional ways of life with modern living, the balance between environmental conservation and urban development, and local superstitions.[32][29] One of its episodes, "Oh! Tok", featuring a spooky banyan tree, won a special Annecy Award for an animated episode of more than 13 minutes in 1999.[33] Although the pilot episode was shown on television in 1997, the series began broadcasting over the satellite television network Astro in 1999.[34] Aside from Malaysia, Kampung Boy was broadcast in other countries such as Germany and Canada.[31]

Reception and legacy

According to Lat, The Kampung Boy's first print—60,000 to 70,000 copies—was sold out in three to four months; by 1979, at least 100,000 had been sold.[35] The Kampung Boy is regarded as Lat's finest work and representative of his oeuvre.[36] After being published in the United States, Kampung Boy won the Children's Book Council and Booklist Editor's Choice award in 2006. It was also awarded the Outstanding International Book for 2007 by the United States Board of Books for Young People.[37]

The Kampung Boy was successful due to its realistic presentation of Malaysia's cultural past. Many Malaysians who grew up in the 1960s or earlier fondly remembered the laidback lives they had in the kampung upon reading the book.[31][34] Stevenson said that The Kampung Boy's portrayal of the past would resonate with everyone's fondness for a happy experience in his or her own past.[38] Those unfamiliar with the ways of the kampung could relate to the "universal themes of childhood, adolescence, and first-love".[39] According to Stevenson, the illustrations help to clarify any unfamiliar terms the reader might face and the narrative force of Lat's story depends more on the protagonist's experiences than on the details.[12] The book's appeal to both children and adults lies in Lat's success in recapturing the innocence of childhood.[15][16]

Malaysian art historian Redza Piyadasa said that "The Kampung Boy was a masterpiece that was clearly designed to be read as a novel."[40] He compared the graphical depiction of childhood experience to Camara Laye's novel The African Child and viewed The Kampung Boy as the "finest and most sensitive evocation of a rural Malay childhood ever attempted in [Malaysia], in any creative medium."[40] Steinberger had the same thoughts, but compared The Kampung Boy to Colin Thiele's autobiographical novel Sun on the Stubble, which expounds on the fun and mischief of early childhood.[16]

Lat's success with The Kampung Boy created new opportunities for him. He set up his own company—Kampung Boy Sendirian Berhad (Village Boy private limited)—to handle the merchandising of his cartoon characters and occasional publishing of his books.[41][42] Kampung Boy is partnering with Sanrio and Hit Entertainment in a project to open an indoor theme park in Malaysia by the end of 2012. One of the park's attractions is the showcasing of Lat's characters alongside those of Hello Kitty and Bob the Builder.[43][44] The distinctive characters of The Kampung Boy have become a common sight in Malaysia. They are immortalised on stamps,[45] financial guides,[46] and aeroplanes.[47]

Sequel and spinoff

Town Boy

Town Boy is the sequel to The Kampung Boy. Published in 1981, it continues Mat's story in the multicultural city of Ipoh, where he attends school, learns of American pop music, and makes new friends of various races, notably a Chinese boy named Frankie. Mat capers through town and gets into mischievous adventures with his friends. He and Frankie bond through their common love of rock-and-roll and playing air-guitar to Elvis Presley's tunes above the coffee shop run by Frankie's parents. As Mat grows into his teens, he dates Normah, "the hottest girl in Ipoh."[48][49] Town Boy's story is a collection of Lat's reminiscences about his teenage days in Ipoh, an account of "the days before [he] moved to the capital city to venture into life as an adult... and later a professional doodler."[50] The cartoonist wanted to publicise his knowledge of music and write a subtle story about friendship. Frankie is representative of the diverse friends Lat made in those days through a common love of music.[35]

The book's layout is more varied than The Kampung Boy's,[49] featuring "short multi-panel sequences with giant double-page-spread-drawings."[51] Comics artist Seth commented that Lat's drawings are filled with "vigor and raw energy", "entirely based on eccentric stylizations but grounded with an eye capable of wonderfully accurate observation of the real world."[51] At certain points, crowd scenes spread across the pages of the book,[49] filled with "Lat's broadly humorous and humane" characters.[52] Comics journalist Tom Spurgeon said after readings such scenes: "There are times when reading Town Boy feels like watching through a street fair after it rains, everyday existence altered by an event just enough to make everything stand out. You can get lost in the cityscapes."[52]

The Asian characters occasionally speak in their native tongues, their words rendered in Chinese or Tamil glyphs without translations. Goldsmith and Ridzwan did not find the foreign words to be a hindrance in understanding and enjoying the work. Instead, they believed the non-English languages aided Lat's construction of his world as one different from a dominantly English-speaking world.[49][23] Lat's depiction of Mat's visit to Frankie's home transcends culture, portraying realistically the experiences most children feel when visiting the "foreign but familiar staleness" of their new friend's home.[51][52] Mat and Frankie's growing friendship is a central theme of the book,[53] and their bond as they enjoy rock-and-roll together in Frankie's house has become a notable scene for readers such as journalist Ridzwan A. Rahim.[23] Their friendship marks a shift in the story of Mat's life from a focus on his family in The Kampung Boy to a focus beyond.[49] As the book revolves around Mat's friendship with Frankie, it ends with the Chinese boy's departure to the United Kingdom from the Ipoh railway station.[51]

As of 2005, Town Boy had been reprinted 16 times.[nb 2] It has also been translated into French and Japanese.[54][55] Reviews of Town Boy were positive. Librarian George Galuschak liked the book for its detailed crowd scenes and its diverse cast of characters—both animal and human.[56] The "energy" in Lat's drawings reminded him of Sergio Aragonés and Matt Groening.[56] Laurel Maury, a reviewer for the Los Angeles Times, likened the book to a Peanuts cartoon, but without the melancholy typical of Charles M. Schulz's work. She said that Lat delivered a "rollicking" world and that his characters' interactions made the story unpretentious and heart-warming.[48] Although Spurgeon believed any single scene in Town Boy was superior to any book from a lesser cartoonist, he preferred the narrower scope of The Kampung Boy; he felt the tighter focus of Lat's first book gave a more personal and deeper insight into the author's growth as a young boy. Town Boy, with its quicker pace, felt to him like a loose collection of heady first-time experiences that failed to explore all possibilities of the encounters.[52]

Kampung Boy: Yesterday and Today

John Lent, a scholar of comics, described Kampung Boy: Yesterday and Today as Lat's "crowning achievement".[35] Published in 1993, Yesterday and Today returns to Lat's roots as a kampung child as described in The Kampung Boy. It explores in greater detail the games played by Lat and his friends and the lifestyle they had in the 1960s. However, Yesterday and Today also compares these past events to similar occurrences in the 1980s and '90s, contrasting the two in a humorous light;[57] the opposition of the two time frames is further enhanced by rendering the portrayals of contemporary scenes in watercolour while those of the past remain in black and white.[35][50] Lat's goal for this book was to "tell his own children how much better it was in the old days."[35]

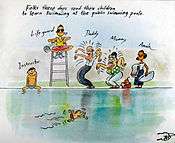

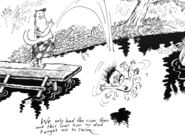

Like in The Kampung Boy, the scenes in Yesterday and Today are presented in great detail. Lat shows the children playing with items constructed from simple items found in the household and nature. He also illustrates the toys' schematics. He compares the games with their modern counterparts, lamenting the loss of creativity in modern youths.[35][34] Other comments on societal changes are in the book. A child is taking a swimming lesson in a pool, intently watched by his parents who have a maid in tow with various items in her hands. While the parents gesticulate wildly at their son, the lifeguard and instructor calmly sit by the pool, watching the boy's smooth progress. This scene is contrasted with Lat's own experience at the hands of his father, who casually tosses the terrified boy into a river, letting him either swim or flounder.[35] Such details, according to Muliyadi, invoke a yearning for the past and help readers "better appreciate [the] cartoons".[34]

University lecturer Zaini Ujang viewed Yesterday and Today's comparisons as criticisms of society, putting forth the question of whether people should accept "development" to simply mean discarding the old for the new without regards to its value.[58] Professor Fuziah of the National University of Malaysia interpreted the book's ending as a wakeup call to parents, questioning them if they should deny their children a more relaxed childhood.[59] Lent agreed, saying that Lat had asserted the theme from the start, showing him and his childhood friends "not in a hurry to grow up".[35] Redza hinted that Lat's other goal was to point out the "dehumanising environment" that Malaysian urban children are growing up in.[60] A Japanese edition of Yesterday and Today was published by Berita Publishing in 1998.[54]

Notes

References

- ↑ From the book, pp. 6–19.

- 1 2 3 4 Goldsmith 2006.

- ↑ From the book, pp. 20–107.

- ↑ From the book, pp. 108–132.

- ↑ From the book, pp. 133–144.

- ↑ Willmott 1989.

- ↑ Gopinath 2009.

- ↑ Crossings: Datuk Lat 2003, 27:05–27:23.

- ↑ Crossings: Datuk Lat 2003, 30:35–31:15.

- ↑ Muliyadi 2004, p. 214.

- ↑ Campbell 2007b.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Stevenson 2007, p. 201.

- 1 2 3 McElhatton 2006.

- ↑ Lockard 1998, pp. 240–241.

- 1 2 Shuttleworth 2010.

- 1 2 3 Steinberger 2009.

- ↑ Campbell 2007a.

- ↑ Rohani 2005, p. 391.

- ↑ Muliyadi 2004, pp. 161–162, 170–171.

- ↑ Redza 2003, pp. 88–91.

- 1 2 Haslina 2008, p. 538.

- ↑ Muhammad Husairy 2006.

- 1 2 3 Ridzwan 2008.

- ↑ Haslina 2008, p. 539.

- ↑ Haslina 2008, pp. 538, 548–549.

- ↑ Haslina 2008, p. 542.

- ↑ Haslina 2008, pp. 539–540, 549.

- ↑ Haslina 2008, pp. 541–542.

- 1 2 Jayasankaran 1999, p. 36.

- 1 2 3 More than a Cartoonist 2007, p. 257.

- ↑ Muliyadi 2001, p. 147.

- ↑ Haliza 1999.

- 1 2 3 4 Muliyadi 2001, p. 145.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Lent 1999.

- ↑ Rohani 2005, p. 390.

- ↑ Azura & Foo 2006.

- ↑ Stevenson 2007, p. 202.

- ↑ Cha 2007.

- 1 2 Redza 2003, p. 94.

- ↑ Lent 2003, p. 261.

- ↑ Chin 1998, p. 60.

- ↑ Satiman & Chuah 2009.

- ↑ Zazali 2009.

- ↑ Kampung Boy Graces 2008.

- ↑ Bank Negara Malaysia 2005.

- ↑ Pillay 2004.

- 1 2 Maury 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Goldsmith 2007.

- 1 2 Campbell 2007c.

- 1 2 3 4 Seth 2006, p. 20.

- 1 2 3 4 Spurgeon 2007.

- ↑ Redza 2003, p. 87.

- 1 2 Lat's Latest 1998.

- ↑ Top 10 Influential Celebrities 2009.

- 1 2 Galuschak 2008, p. 32.

- ↑ Fuziah 2007, pp. 5–6.

- ↑ Zaini 2009, pp. 205–206.

- ↑ Fuziah 2007, p. 6.

- ↑ Redza 2003, p. 96.

Bibliography

Interviews/self-introspectives

- Lat (11 January 2007). "Campbell Interviews Lat: Part 1". First Hand Books—Doodles and Dailies (Interview). Interview with Campbell, Eddie. New York, United States: First Second Books. Archived from the original on 23 June 2008. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- Lat (12 January 2007). "Campbell Interviews Lat: Part 2". First Hand Books—Doodles and Dailies (Interview). Interview with Eddie Campbell. New York, United States: First Second Books. Archived from the original on 23 June 2008. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- Lat (15 January 2007). "Campbell Interviews Lat: Part 3". First Hand Books—Doodles and Dailies (Interview). Interview with Eddie Campbell. New York, United States: First Second Books. Archived from the original on 23 June 2008. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

Books

- Chin, Phoebe, ed. (March 1998). "The Kampung Boy". S-Files, Stories Behind Their Success: 20 True Life Malaysian Stories to Inspire, Challenge, and Guide You to Greater Success. Selangor, Malaysia: Success Resources Slipguard. ISBN 983-99324-0-3.

- Lockard, Craig (1998). "Popular Music and Political Change in the 1980s". Dance of Life: Popular Music and Politics in Southeast Asia. Hawaii, United States: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 238–247. ISBN 0-8248-1918-7. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- Muliyadi Mahamood (2004). The History of Malay Editorial Cartoons (1930s–1993). Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Utusan Publications and Distributions. ISBN 967-61-1523-1.

- Redza Piyadasa (2003). "Lat the Cartoonist—An Appreciation". Pameran Retrospektif Lat [Retrospective Exhibition 1964–2003]. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: National Art Gallery. pp. 84–99. ISBN 983-9572-71-7.

- Seth (2006). Forty Cartoon Books of Interest: From the Collection of the Cartoonist "Seth". California, United States: Buenaventura Press.

- Zaini Ujang (2009). "Books Strengthen the Mind". The Elevation of Higher Learning. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Malaysian National Institute of Translation. pp. 201–208. ISBN 983-068-464-4. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

Academic sources

- Fuziah Kartini Hassan Basri (April–June 2007). "Walking with Lat in Kampung Boy—Yesterday and Today" (PDF). Resonance. Selangor, Malaysia: National University of Malaysia (15): 5–6. ISSN 1675-7270. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

- Galuschak, George (2008). "Lat. Town Boy.". Kliatt. Massachusetts, United States. 42 (2): 32. ISSN 1065-8602. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- Goldsmith, Francisca (15 September 2006). "Kampung Boy". Booklist. Vol. 103 no. 2. Illinois, United States: American Library Association. p. 61. ISSN 0006-7385. Proquest ID: 1134269391. Retrieved 17 April 2010. (subscription required (help)).

- Goldsmith, Francisca (1 September 2007). "Town Boy". Booklist. Vol. 104 no. 1. Illinois, United States: American Library Association. p. 109. ISSN 0006-7385. Proquest ID: 1334735641. Retrieved 17 April 2010. (subscription required (help)).

- Haslina Haroon (2008). "The Adaptation of Lat's The Kampung Boy for the American Market". Membina Kepustakaan Dalam Bahasa Melayu [Build a Library in the Malay language]. International Conference on Translation. 11. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Malaysian National Institute of Translation. pp. 537–549. ISBN 983-192-438-X. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- Lent, John (April 1999). "The Varied Drawing Lots of Lat, Malayasian Cartoonist". The Comics Journal. Washington, United States: Fantagraphics Books (211): 35–39. ISSN 0194-7869. Archived from the original on 15 February 2005. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- Lent, John (Spring 2003). "Cartooning in Malaysia and Singapore: The Same, but Different". International Journal of Comic Art. 5 (1): 256–289. ISSN 1531-6793.

- Muliyadi Mahamood (2001). "The History of Malaysian Animated Cartoons". In Lent, John. Animation in Asia and the Pacific. Indiana, United States: Indiana University Press. pp. 131–152. ISBN 0-253-34035-7.

- Rohani Hashim (2005). "Lat's Kampong Boy: Rural Malays in Tradition and Transition". In Palmer, Edwina. Asian Futures, Asian Traditions. Kent, United Kingdom: Global Oriental. pp. 389–400. ISBN 1-901903-16-8.

- Stevenson, Deborah (January 2007). "The Big Picture—Kampung Boy". The Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books. Maryland, United States: Johns Hopkins University Press. 60 (5): 201–202. doi:10.1353/bcc.2007.0046. ISSN 0008-9036. Proquest ID: 1190715481. Retrieved 17 April 2010. (subscription required (help)).

Journalistic sources

- Azura Abas; Foo, Heidi (16 December 2006). "Lat's "Kampung Boy" Makes It Big in US". New Straits Times. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: New Straits Times Press. p. 10. ProQuest ID: 1181979521. Retrieved 14 March 2010. (subscription required (help)).

- Cha, Kai-Ming (20 November 2007). "Lat's Malaysian Memories". PW Comics Week. New York, United States: Publishers Weekly. Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- Crossings: Datuk Lat (Television production). Singapore: Discovery Networks Asia. 21 September 2003.

- Gopinath, Anandhi (8 June 2009). "Cover: Our Kampung Boy". The Edge. Selangor, Malaysia: The Edge Communications Sdn Bhd (758). Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- Haliza Ahmad (24 December 1999). "Annecy Awards '99 for Lat's Kampung Boy". The Malay Mail. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: New Straits Times Press. p. 15. Proquest ID: 47449038. Retrieved 24 July 2010. (subscription required (help)).

- Jayasankaran, S (22 July 1999). "Going Global". Far Eastern Economic Review. Hong Kong: Dow Jones & Company. 162 (29): 35–36. ISSN 0014-7591. Proquest ID: 43402018. Retrieved 12 March 2010. (registration required (help)).

- "Kampung Boy Graces Our Stamps". The Star. Selangor, Malaysia: Star Publications. 27 November 2008. Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- "Lat's Latest". New Straits Times. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: New Straits Times Press. 18 March 1998. p. 7. ProQuest ID: 27524668. Retrieved 14 March 2010. (subscription required (help)).

- Manavalan, Theresa (4 July 1999). "Kampung Boy Hits Big Time". New Sunday Times. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: New Straits Times Press. p. 10. Proquest ID: 42901498. Retrieved 18 May 2010.

- "More than a Cartoonist". Annual Business Economic and Political Review: Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Oxford Business Group. 2 (Emerging Malaysia 2007): 257–258. January 2007. ISSN 1755-232X. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

- Muhammad Husairy Othman (14 February 2006). "'Kampung Boy' arrives in Brazil". New Straits Times. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: New Straits Times Press. p. 13. Proquest ID: 986223671. Retrieved 24 July 2010. (subscription required (help)).

- Pillay, Suzanna (26 May 2004). "Airborne with the Kampung Boy". New Straits Times. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: New Straits Times Press. p. 5. Proquest ID: 642258141. Retrieved 4 July 2010. (subscription required (help)).

- Ridzwan A. Rahim (31 August 2008). "Here's the Lat-est". New Straits Times. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: New Straits Times Press. p. 2. ProQuest ID: 1545672011. Retrieved 25 June 2010. (subscription required (help)).

- Satiman Jamin; Chuah, Bee Kim (12 November 2009). "First Indoor Theme Park Set in Nusajaya". New Straits Times. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: New Straits Times Press. Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- Shuttleworth, Mike (15 January 2010). "Kampung Boy". The Age. Melbourne, Australia: Fairfax Media. Archived from the original on 27 August 2010. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- Steinberger, Kevin (November 2009). "Kampung Boy". Magpies. New South Wales, Australia: Magpies Magazine. 24 (5): 22. ISSN 0034-0375.

- Willmott, Jennifer Rodrigo (March 1989). "Malaysia's Favourite Son". Reader's Digest. Vol. 134 no. 803. New York, United States: The Reader's Digest Association. ISSN 0034-0375. Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- "Top 10 Influential Celebrities in Malaysia: Stars with the X-factor Sizzle". AsiaOne. Singapore: Singapore Press Holdings. New Straits Times. 7 September 2009. Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- Zazali Musa (10 November 2009). "Johor Not Competing with Singapore for Theme Park Visitors". The Star Online. Selangor, Malaysia: Star Publications. Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

Online sites

- "Bank Negara Malaysia Releases "Buku Wang Saku" and "Buku Perancangan dan Penyata Kewangan Keluarga" for 2006" (Press release). Bank Negara Malaysia. 29 December 2005. Archived from the original on 27 May 2006. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- Maury, Laurel (26 December 2007). "Lat's Rollicking Malaysian Childhood". Jacket Copy. Los Angeles, United States: Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- McElhatton, Greg (30 August 2006). "Kampung Boy". Read About Comics. Washington D.C., United States: Self-published. Archived from the original on 24 February 2008. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- Spurgeon, Tom (20 July 2007). "CR Review: Town Boy". The Comics Reporter. New Mexico, United States: Self-published. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

External links

- "Kampung Boy (with sample images)". Macmillan Academics. New York, United States: Macmillan Publishers. 2008. Retrieved 8 November 2010.

- "Town Boy (with sample images)". Macmillan Academics. New York, United States: Macmillan Publishers. 2008. Retrieved 8 November 2010.