United States presidential election, 1792

| | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

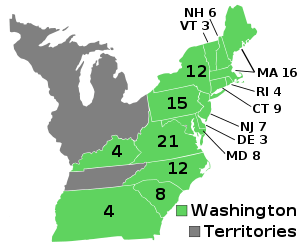

| Presidential election results map. Numbers indicate the number of electoral votes allotted to each state. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The United States presidential election of 1792 was the second quadrennial presidential election. It was held from Friday, November 2 to Wednesday, December 5, 1792. Incumbent President George Washington was elected to a second term by a unanimous vote in the electoral college. As in the first presidential election, Washington is considered to have run unopposed. Electoral rules of the time, however, required each presidential elector to cast two votes without distinguishing which was for president and which for vice president. The recipient of the most votes would then become president, and the runner-up vice president. Incumbent Vice President John Adams received 77 votes and was also re-elected (Washington received 132 votes, or one from each elector).

This election was the first in which each of the original 13 states appointed electors (in addition to the newly added states of Kentucky and Vermont). It was also the only presidential election that was not held exactly four years after the previous election, although part of the previous election was technically held four years prior. The second inauguration was on March 4, 1793 at the Senate Chamber of Congress Hall in Philadelphia.

Candidates

In 1792, presidential elections were still conducted according to the original method established under the U.S. Constitution. Under this system, each elector cast two votes: the candidate who received the greatest number of votes (so long as they won a majority) became president, while the runner-up became vice president. The Twelfth Amendment would eventually replace this system, requiring electors to cast one vote for president and one vote for vice president, but this change did not take effect until 1804. Because of this, it is difficult to use modern-day terminology to describe the relationship between the candidates in this election.

Washington is generally held by historians to have run unopposed. Indeed, the incumbent president enjoyed bipartisan support and received one vote from every elector. The choice for vice president was more divisive. The Federalist Party threw its support behind the incumbent vice president, John Adams of Massachusetts, while the Democratic-Republican Party backed the candidacy of New York Governor George Clinton. Because few doubted that Washington would receive the greatest number of votes, Adams and Clinton were effectively competing for the vice presidency; under the letter of the law, however, they were technically candidates for president competing against Washington.

Federalist nomination

- George Washington, President of the United States from Virginia

- John Adams, Vice President of the United States from Massachusetts

Democratic-Republican nomination

- George Washington, President of the United States from Virginia

- George Clinton, Governor of New York

Born out of the Anti-Federalist faction that had opposed the Constitution in 1788, the Democratic-Republican Party (sometimes simply called "Republicans", although there was no connection to the modern-day Republican Party) was the main opposition to the agenda of Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton. They had no chance of unseating Washington, but hoped to win the vice presidency by defeating the incumbent, Adams. The Republicans would have preferred to nominate Thomas Jefferson, their ideological leader and Washington's Secretary of State. However, this would have cost them the state of Virginia, as electors were not permitted to vote for two candidates from their home state and Washington was also a Virginian. Instead, they settled on Governor George Clinton, though Jefferson would receive the votes of four Kentucky electors.

-

Governor

George Clinton

of New York

Campaign

By 1792, a party division had emerged between Federalists led by Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton, who desired a stronger federal government with a leading role in the economy, and the Democratic-Republicans led by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and Representative James Madison of Virginia, who favored states' rights and opposed Hamilton's economic program. Madison was at first a Federalist until he opposed the establishment of Hamilton's First Bank of the United States in 1791. He formed the Democratic-Republican Party along with Anti-Federalist Thomas Jefferson in 1792.

The elections of 1792 were the first ones in the United States to be contested on anything resembling a partisan basis. In most states, the congressional elections were recognized in some sense as a "struggle between the Treasury department and the republican interest," to use the words of Jefferson strategist John Beckley. In New York, the race for governor was fought along these lines. The candidates were Chief Justice John Jay, a Hamiltonian, and incumbent George Clinton, who was allied with Jefferson and the Democratic-Republicans.

Although Washington had been considering retiring, both sides encouraged him to remain in office to bridge factional differences. Washington was supported by practically all sides throughout his presidency and gained more popularity with the passage of the Bill of Rights. However, the Democratic-Republicans and the Federalists contested the vice-presidency, with incumbent John Adams as the Federalist nominee and George Clinton as the Democratic-Republican nominee. With some Democratic-Republican electors voting against their nominee George Clinton – voting instead for Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr – Adams easily secured re-election.

Results

At the time, there were 15 states in the United States: the 13 original states and the two recently admitted states of Vermont (March 1791) and Kentucky (June 1792). The Electoral College consisted of 132 electors, with each elector having two votes.

The Electoral College chose Washington unanimously. John Adams was again elected vice-president as the runner-up, this time getting the vote of a majority of electors. George Clinton won the votes of only Georgia, North Carolina, Virginia, his native New York, and a single elector in Pennsylvania. Thomas Jefferson won the votes of Kentucky, newly separated from Jefferson's home state of Virginia. A single South Carolina elector voted for Aaron Burr. All five of these candidates would eventually win election to the offices of president or vice president.

Only two states, Pennsylvania and Maryland, cast popular votes. Overall there were 28,579 popular votes cast for presidential electors, a record low turnout for a United States presidential election.

Popular vote

| Slate | Popular Vote(a), (b), (c) | |

|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | |

| Federalist electors | 26,088 | 91.28% |

| Democratic-Republican electors | 2,491 | 8.72% |

| Total | 28,579 | 100.0% |

Source: U.S. President National Vote. Our Campaigns. (February 11, 2006). Source (Popular Vote): A New Nation Votes: American Election Returns 1787-1825[1]

(a) Only 6 of the 15 states chose electors by any form of popular vote.

(c) Those states that did choose electors by popular vote had widely varying restrictions on suffrage via property requirements.

Electoral vote

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote(a) | Electoral vote(b) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | ||||

| George Washington (Incumbent) | None | Virginia | 28,579 | 100.0% | 132 |

| John Adams | Federalist | Massachusetts | — | — | 77 |

| George Clinton | Democratic-Republican | New York | — | — | 50 |

| Thomas Jefferson | Democratic-Republican | Virginia | — | — | 4 |

| Aaron Burr | Democratic-Republican | New York | — | — | 1 |

| Total | 28,579 | 100.0% | 264 | ||

| Needed to win | 67 | ||||

Source: "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 30, 2005.

(a) (1) only 6 of the 15 states chose electors by any form of popular vote, (2) pre-Twelfth Amendment electoral vote rules obscure the intentions of the voters, and (3) those states that did choose electors by popular vote restricted the vote via property requirements.

(b) Two electors from Maryland and one elector from Vermont did not cast votes.

Electoral college selection

The Constitution, in Article II, Section 1, provided that the state legislatures should decide the manner in which their Electors were chosen. Different state legislatures chose different methods:[2]

| Method of choosing electors | State(s) |

|---|---|

| state is divided into electoral districts, with one elector chosen per district by the voters of that district | Kentucky Virginia |

| each elector chosen by voters statewide | Maryland Pennsylvania |

|

Massachusetts |

|

New Hampshire |

| each elector appointed by the state legislature | (all other states) |

See also

- First Party System

- History of the United States (1789–1849)

- United States House of Representatives elections, 1792

- United States Senate elections, 1792 and 1793

References

- ↑ http://elections.lib.tufts.edu/catalog?commit=Limit&f%5Belection_type_sim%5D%5B%5D=General&f%5Boffice_id_ssim%5D%5B%5D=ON056&page=2&q=1820&range%5Bdate_sim%5D%5Bbegin%5D=1820&range%5Bdate_sim%5D%5Bend%5D=1820&search_field=all_fields&utf8=%E2%9C%93

- ↑ "The Electoral Count for the Presidential Election of 1789". The Papers of George Washington. Archived from the original on 14 Sep 2013. Retrieved May 4, 2005.

Bibliography

- Berg-Andersson, Richard (September 17, 2000). "A Historical Analysis of the Electoral College". The Green Papers. Retrieved March 20, 2005.

- Elkins, Stanley; McKitrick, Eric (1995). The Age of Federalism. Oxford University Press.

- A New Nation Votes: American Election Returns, 1787-1825

External links

- Presidential Election of 1792: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- Election of 1792 in Counting the Votes

.jpg)