Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site

|

White Haven; Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site | |

| |

| |

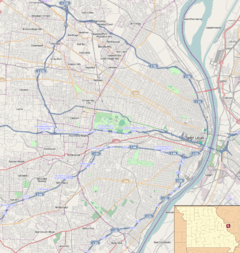

| Nearest city | Grantwood Village, Missouri |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 38°33′4″N 90°21′7″W / 38.55111°N 90.35194°WCoordinates: 38°33′4″N 90°21′7″W / 38.55111°N 90.35194°W |

| Area | 9.9 acres (4.0 ha) |

| Built | 1795 |

| Website | Ulsses S. Grant National Historic Site |

| NRHP Reference # | 79003205[1] |

| Added to NRHP | April 4, 1979 |

Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site is a 9.65-acre (39,100 m2) United States National Historic Site located 10 miles (16 km) southwest of Downtown St. Louis, Missouri within the municipality of Grantwood Village. The site, also known as White Haven, commemorates the life, military career, and Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant. Five historic structures are preserved at the site including the childhood home of Julia Dent Grant, wife of Ulysses S. Grant.

White Haven was a plantation worked by slaves at the time Grant was married to his wife in 1848 and remained so until the end of the American Civil War.

History

After his marriage to Julia, Grant was stationed in Michigan and New York. Julia traveled with him to these posts, returning to White Haven in 1850 for the birth of their first child, Fred, in 1850. When Ulysses was sent west in 1852, Julia was not able to go with him, being pregnant with their second child. She returned to her parents' home after stopping at Ulysses' parents' home in Ohio, where Ulysses Jr., was born. Grant's army pay was insufficient to bring his family out to the West Coast, and he tried several business ventures to supplement his income. Suffering from depression and loneliness after being separated for two years, Grant finally resigned from the army in 1854 and returned to White Haven.[2]

Grant farmed the White Haven property for his father-in-law, working with the slaves owned by Julia's father. Two more children were born, Ellen, born on July 4, 1855, and Jesse, in February 1858. Due to a financial panic in 1857, along with bad weather that destroyed many farmer's crops, Ulysses worked for a short time in the city of St. Louis in real estate and as an engineer. In 1860, Ulysses, Julia, and their four children moved to Galena, Illinois. Ulysses worked with his brothers selling leather goods made in their father's tannery.[2]

Slavery at White Haven

Many visitors to Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site are surprised to learn that slaves lived and worked on the nineteenth century farm known as White Haven. During the years 1854 to 1859 Grant lived here with his wife, Julia, and their children, managing the farm for his father-in-law, Colonel Dent. At that time no one suspected that Grant would rise from obscurity to achieve the success he gained during the Civil war. However, his experience working alongside the White Haven slaves may have influenced him in his later roles as the Union general who won the war which abolished that "peculiar institution," and as President of the United States. The interpretation of slavery at White Haven is therefore an important part of the mission of this historic site.[3]

The setting

Most slaveholders in Missouri owned few slaves; those who owned ten were considered wealthy. In the southeastern Bootheel area and along the fertile Missouri River valley known as "little Dixie," large, single-crop plantations predominated, with an intensive use of slave labor. Elsewhere in the state, large farms produced a variety of staples, including hemp, wheat, oats, hay, and corn. On many of these estates the owner worked alongside his slaves to harvest the greatest economic benefit from the land. Slavery was less entrenched in the city of St. Louis, where the African American population was 2% in 1860, down from 25% in 1830. Slaves were often "hired out" by their masters in return for an agreed upon wage. A portion of the wage was sometimes paid to slaves, allowing a measure of self-determination and in some cases the opportunity to purchase their freedom.[3]

Early farm residents and slavery

Each of the farm's early residents owned slaves during their tenure on the Gravois property. When Theodore and Anne Lucas Hunt purchased William Lindsay Long's home in 1818, there existed "several good log cabins" on the property—potential quarters for the five slaves purchased earlier by Hunt. The work of Walace, Andrew, Lydia, Loutette, and Adie would be an important part of the Hunts' farming venture. The Hunts sold the Gravois property to Frederick Dent in 1820, for the sum of $6,000. Naming the property "White Haven" after his family home in Maryland, Colonel Dent considered himself a Southern gentleman with slaves to do the manual labor of caring for the plantation. By the 1850s, eighteen slaves lived and worked at White Haven.[3]

Growing up as a slave

In 1830, half of the Dent slaves were under the age of ten. Henrietta, Sue, Ann, and Jeff, among others, played with the Dent children. Julia Dent recalled that they fished for minnows, climbed trees for bird nests, and gathered strawberries. However, the slave children also had chores such as feeding chickens and cows, and they mastered their assigned tasks as the white children went off to school. Returning home from boarding school, Julia noted the transition from playmate to servant. She noted that the slave girls had "attained the dignity of white aprons." These aprons symbolized slave servitude, a departure from the less structured days of childhood play.[3]

Household responsibilities

Adult slaves performed many household chores on the Dent plantation. Kitty and Rose served as nurses to Julia and Emma, while Mary Robinson became the family cook. The wide variety of foods prepared in her kitchen were highly praised by Julia: "Such loaves of beautiful snowy cake, such plates full of delicious Maryland biscuit, such exquisite custards and puddings, such omelettes, gumbo soup, and fritters." A male slave named "Old Bob," who traveled with the Dents from Maryland in 1816, had the responsibility to keep the fires going in White Haven's seven fireplaces. Julia thought Bob was careless to allow the embers to die out, as this forced him "to walk a mile to some neighbors and bring home a brand of fire from their backlog." Such "carelessness" provided Bob and many other slaves an opportunity to escape their masters' eyes.[3]

Tending the farm

Slave labor was used extensively in the farming and maintenance of the 850-acre plantation. Utilizing the "best improvements in farm machinery" owned by Colonel Dent, field hands plowed, sowed and reaped the wheat, oats, Irish potatoes, and Indian corn grown on the estate. Slaves also cared for the orchards and gardens, harvesting the fruits and vegetables for consumption by all who lived on the property. During Grant's management of the farm he worked side by side with Dan, one of the slaves given to Julia at birth. Grant, along with Dan and other slaves, felled trees and took firewood by wagon to sell to acquaintances in St. Louis. More than 75 horses, cattle, and pigs required daily attention, while grounds maintenance and numerous remodeling projects on the main house and outbuildings utilized the skills of those in servitude.[3]

Personal lives

Slaves claimed time for socializing amidst their chores. Corn shuckings provided one opportunity to come together as a community to eat, drink, sing, and visit, often including slaves from nearby plantations. Participation in religious activities, individually or as a group, also provided a sense of integrity. Julia remembered "Old Bob" going into the meadow to pray and sing. According to historian Lorenzo J. Greene, "St. Louis…was the only place in the state where the organized black church achieved any measure of success." Whether or not the Dent slaves were allowed to attend services is unknown.[3]

Freedom

In Mary Robinson's July 24, 1885, recollections, during an interview for the St. Louis Republican memorial to Grant following his death, she noted that "he always said he wanted to give his wife's slaves their freedom as soon as he was able." In 1859, Grant freed William Jones, the only slave he is known to have owned. During the Civil War, some slaves at White Haven simply walked off, as they did on many plantations in both Union and Confederate states. Missouri's constitutional convention abolished slavery in the state in January 1865, freeing any slaves still living at White Haven.

"I Ulysses S. Grant... do hereby manumit, emancipate and set free from Slavery my Negro man William, sometimes called William Jones... forever."[3]

In 1989, the site became a part of the National Park Service and is currently one of 413 sites managed by that agency. The current superintendent is Timothy S. Good.

See also

- General Grant National Memorial (Grant's Tomb)

- Grant Cottage State Historic Site, Mt. McGregor, New York

- Ulysses S. Grant Home, Galena, Illinois

- Grant Boyhood Home, Georgetown, Ohio

- Grant Birthplace, Point Pleasant, Ohio

- Grant's Farm

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service website http://www.nps.gov/ulsg/historyculture/ulysses-s-grant.htm (retrieved on November 3, 2014).

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service website http://www.nps.gov/ulsg/historyculture/ulysses-s-grant.htm (retrieved on November 3, 2014).

- ↑ National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 "Ulysses S. Grant". National Park Service.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Slavery at White Haven". National Park Service.

Other sources

- Casey, Emma Dent. "When Grant Went A-Courtin'." Unpublished manuscript, Ulysses S. Grant NHS collection.

- Grant, Julia Dent. The Personal Memoirs of Julia Dent Grant (Mrs. Ulysses S. Grant). Southern Illinois University Press, 1988.

- Greene, Lorenzo, et al. Missouri's Black Heritage. University of Missouri Press, 1993.

- Hurt, R. Douglas. Agriculture and Slavery in Missouri's Little Dixie. University of Missouri Press, 1992.

- Vlach, John Michael. Back of the Big House. University of North Carolina Press, 1993.

- Wade, Richard C. Slavery in the Cities: The South 1820-1860. Oxford University Press, 1964.

External links

![]() Media related to Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site at Wikimedia Commons

- National Park Service: Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site.

- St. Louis Convention and Visitors Commission web site

| This article or image contains material based on a work of a National Park Service employee, created as part of that person's official duties. As a work of the U.S. federal government, such work is in the public domain in the United States. See the NPS website and NPS copyright policy for more information. Note that not all images on NPS websites are in the public domain. Please be sure that this template is only used for images that are not attributed to a copyright holder. |  |