When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd

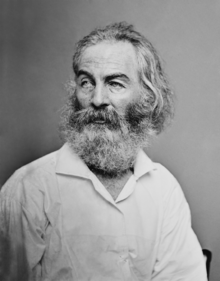

| by Walt Whitman | |

The poem's first page in the 1865 edition of Sequel to Drum-Taps | |

| Written | 1865 |

|---|---|

| First published in | Sequel to Drum-Taps (1865) |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Form | Pastoral elegy |

| Meter | Free verse |

| Publisher |

Gibson Brothers (Washington, DC) |

| Publication date | 1865 |

| Lines | 206 |

| Read online | When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd at Wikisource |

"When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd" is a long poem in the form of an elegy written by American poet Walt Whitman (1819–1892) in 1865.

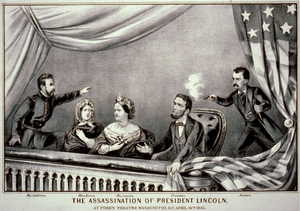

The poem, written in free verse in 206 lines, uses many of the literary techniques associated with the pastoral elegy. It was written in the summer of 1865 during a period of profound national mourning in the aftermath of the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln on April 14, 1865. Despite the poem being an elegy to the fallen president, Whitman neither mentions Lincoln by name nor discusses the circumstances of his death. Instead, Whitman uses a series of rural and natural imagery including the symbols of the lilacs, a drooping star in the western sky (Venus), and the hermit thrush, and employs the traditional progression of the pastoral elegy in moving from grief toward an acceptance and knowledge of death. The poem also addresses the pity of war through imagery vaguely referencing the American Civil War (1861–1865) which ended only days before the assassination.

"When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd" was written ten years after publishing the first edition of Leaves of Grass (1855) and it reflects a maturing of Whitman's poetic vision from a drama of identity and romantic exuberance that has been tempered by his emotional experience of the American Civil War. Whitman included the poem as part of a quickly-written sequel to a collection of poems addressing the war that was being printed at the time of Lincoln's death. These poems, collected under the title Drum-Taps and Sequel to Drum-Taps, range in emotional context from "excitement to woe, from distant observation to engagement, from belief to resignation" and "more concerned with history than the self, more aware of the precariousness of America's present and future than of its expansive promise."[1] First published in autumn 1865, "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd"—along with 42 other poems from Drum-Taps and Sequel to Drum-Taps—was absorbed into Leaves of Grass beginning with the fourth edition, published in 1867.

Although Whitman did not consider the poem to be among his best works, it is compared in both effect and quality to several acclaimed works of English literature, including elegies such as John Milton's Lycidas (1637) and Percy Bysshe Shelley's Adonaïs (1821).

Writing history and background

In the late 1850s and early 1860s, Whitman established his reputation as a poet with the release of Leaves of Grass. Whitman intended to write a distinctly American epic and developed a free verse style inspired by the cadences of the King James Bible.[2][3] The small volume, first released in 1855, was considered controversial by some, with critics attacking Whitman's verse as "obscene".[4] However, it attracted praise from American Transcendentalist essayist, lecturer, and poet Ralph Waldo Emerson, which contributed to fostering significant interest in Whitman's work.[5][6][7]

At the start of the American Civil War, Whitman moved from New York to Washington, D.C., where he obtained work in a series of government offices, first with the Army Paymaster's Office and later with the Bureau of Indian Affairs.[8][9] He volunteered in the army hospitals as a "hospital missionary."[10] His wartime experiences informed his poetry which matured into reflections on death and youth, the brutality of war, patriotism, and offered stark images and vignettes of the war.[11] Whitman's brother, George Washington Whitman, had been taken prisoner in Virginia on September 30, 1864 and was held for five months in Libby Prison, a Confederate prisoner-of-war camp near Richmond, Virginia.[12] On February 24, 1865, George was granted a furlough to return home because of his poor health, and Whitman had travelled to his mother's home in New York to visit his brother.[13] While visiting Brooklyn, Whitman contracted to have his collection of Civil War poems, Drum-Taps, published.[14]

The Civil War had ended and a few days later, on April 14, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln was shot by John Wilkes Booth while attending the performance of a play at Ford's Theatre. Lincoln died the following morning. Whitman was at his mother's home when he heard the news of the president's death; in his grief he stepped outside the door to the yard, where the lilacs were blooming.[14] Many years later, Whitman recalled the weather and conditions on the day that Lincoln died in Specimen Days where he wrote:

I remember where I was stopping at the time, the season being advanced, there were many lilacs in full bloom. By one of those caprices that enter and give tinge to events without being at all a part of them, I find myself always reminded of great tragedy of that day by the sight and odor of these blossoms. It never fails.[15]

Lincoln was the first American president to be assassinated and his death had a long-lasting emotional impact upon the United States. Over the three weeks after his death, millions of Americans participated in a nationwide public pageant of grief, including a state funeral, and the 1,700-mile (2,700 km) westward journey of the funeral train from Washington, through New York, to Springfield, Illinois.[16][17]

Lincoln's public funeral in Washington was held on April 19, 1865. Some biographies indicate that Whitman journeyed to Washington to attend the funeral and possibly observed Lincoln's body during the viewing held in the East Room of the White House. Whitman biographer Jerome Loving believes that Whitman did not attend the public ceremonies for Lincoln in Washington as he did not leave Brooklyn for the nation's capital until April 21. Likewise, Whitman could not have attended ceremonies held in New York after the arrival of the funeral train, as they were observed on April 24. Loving thus suggests that Whitman's descriptions of the funeral procession, public events and the long train journey may have been "based on second-hand information". He does accede that Whitman in his journey from New York to Washington may have passed the Lincoln funeral train on its way to New York—possibly in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.[18]

Publication history

On April 1, 1865, Whitman had signed a contract with Brooklyn printer Peter Eckler to publish Drum-Taps, a 72-page collection of 43 poems in which Whitman addressed the emotional experiences of the Civil War.[14] Drum-Taps was being printed at the time of Lincoln's assassination two weeks later. Upon learning of the president's death, Whitman delayed the printing to insert a quickly-written poem, "Hush'd Be the Camps To-Day", into the collection.[14][19] The poem's subtitle indicates it was written on April 19, 1865—four days after Lincoln's death. Whitman intended to supplement Drum-Taps with several additional Civil War poems and a handful of new poems mourning Lincoln's death that he had written between April and June 1865.

Upon returning to Washington, Whitman contracted with Gibson Brothers to publish a pamphlet of eighteen poems that included two works directly addressing the assassination—"When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd" and "O Captain! My Captain!". He intended to include the pamphlet with copies of Drum-Taps.[14] The 24-page collection was titled Sequel to Drum-Taps and bore the subtitle When Lilacs Last in the Door-Yard Bloom'd and other poems.[14] The title poem filled the first nine pages.[20] In October, after the pamphlet was printed, he returned to Brooklyn to have them integrated with Drum-Taps.[14]

Whitman added the poems from Drum-Taps and Sequel to Drum-Taps as a supplement to the fourth edition of Leaves of Grass printed in 1867 by William E. Chapin.[21][22] Whitman revised his collection Leaves of Grass throughout his life, and each additional edition included newer works, his previously published poems often with revisions or minor emendations, and reordering of the sequence of the poems. The first edition (1855) was a small pamphlet of twelve poems. At his death four decades later, the collection included over 400 poems. For the fourth edition (1867)—in which "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd" had first been included—Leaves of Grass had been expanded to a collection of 236 poems. However, University of Nebraska literature professor Kenneth Price and University of Iowa English professor Ed Folsom describe the 1867 edition as "the most carelessly printed and most chaotic of all the editions" citing errata and conflicts with typsetters.[23] Price and Folsom note that book had five different formats—some including the Drum-Taps poems; some without.[23]

"When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd" and his other three Lincoln Poems "O Captain! My Captain", "Hush'd be the Camps To-day", "This Dust Was Once the Man" (1871) were included in subsequent editions of Leaves of Grass, although in Whitman's 1871 and 1881 editions it was separated from Drum-Taps. In the 1871 edition, Whitman's four Lincoln poems were listed as a cluster titled "President Lincoln's Burial Hymn". In the 1881 edition, this cluster was renamed "Memories of President Lincoln".[24][25][26] Whitman considered the 1881 edition to be final—although the subsequent "Deathbed Edition" compiled 1891–1892 corrected grammatical errors from the 1881 edition and add three minor works.[27] Leaves of Grass has never been out of print since its first publication in 1855, and "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd" is among several poems from the collection that appear frequently in poetry anthologies.[28][29][30][31]

Analysis and interpretation

Structure

"When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd" is a first-person monologue written in free verse. It is a long poem, 206 lines in length (207 according to some sources), that is cited as a prominent example of the elegy form and of narrative poetry.[32] In its final form, published in 1881 and republished to the present, the poem is divided into sixteen sections referred to as cantos or strophes that range in length from 5 or 6 lines to as many as 53 lines.[33] The poem does not possess a consistent metrical pattern, and the length of each line varies from seven syllables to as many as twenty syllables. Literary scholar Kathy Rugoff says that "the poem... has a broad scope and incorporates a strongly characterized speaker, a complex narrative action and an array of highly lyrical images."[34]

The first version of "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd" that appeared in 1865 was arranged into 21 strophes.[35] It was included with this structure in the fourth edition of Leaves of Grass that was published in 1867.[21] By 1871, Whitman had combined the strophes numbered 19 and 20 into one, and the poem had 20 in total.[36] However, for the seventh edition (1881) of Leaves of Grass, Whitman rearranged the poem's final seven strophes of his original text were combined into the final three strophes of the 16-strophe poem that is familiar to readers today.[37] For the 1881 edition, the original strophes numbered 14, 15, and 16 were combined into the revised 14th strophe; strophes numbered 17 and 18 were combined into the revised 15th strophe. The material from the former strophes numbered 19, 20 and 21 in 1865 were combined for the revised 16th and final strophe in 1881.[35] According to literary critic and Harvard University professor Helen Vendler, the poem "builds up to its longest and most lyrical moment in canto 14, achieves its moral climax in canto 15, and ends with a coda of 'retrievements out of the night' in canto 16."[33]

Narrative

While Whitman's "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd" is an elegy to the fallen president, it does not mention him by name or the circumstances surrounding his death. This is not atypical; Whitman biographer Jerome Loving states that "traditionally elegies do not mention the name of the deceased in order to allow the lament to have universal application".[38] According to Rugoff, the poem's narrative is given by an unnamed speaker, adding:

The speaker expresses his sorrow over the death of 'him I love' and reveals his growing consciousness of his own sense of the meaning of death and the consolation he paradoxically finds in death itself. The narrative action depicts the journey of Lincoln's coffin without mentioning the president by name and portrays visions of 'the slain soldiers of war' without mentioning either the Civil War or its causes. The identifications are assumed to be superfluous, even tactless; no American could fail to understand what war was meant. Finally, in the 'carol of the bird,' the speaker recounts the song in which death is invoked, personified and celebrated."[39]

According to Vendler, the speaker's first act is to break off a sprig from the lilac bush (line 17) that he subsequently lays on Lincoln's coffin during the funeral procession—"Here, coffin that slowly passes, / I give you my sprig of lilac." (line 44–45).[33]

Style and techniques

Whitman's biographers explain that Whitman's verse is influenced by the aesthetics, musicality and cadences of phrasing and passages in the King James Bible.[40][5] Whitman employs several techniques of parallelism—a device common to Biblical poetry.[41][42] While Whitman does not use end rhyme, he employs internal rhyme in passages throughout the poem. Although Whitman's free verse does not utilise a consistent pattern of meter or rhyme, the disciplined use of other poetic techniques and patterns to create a sense of structure. His poetry achieves a sense of cohesive structure and beauty through the internal patterns of sound, diction, specific word choice, and effect of association.[43]

The poem uses many of the literary techniques associated with the pastoral elegy; a meditative lyric genre derived from the poetic tradition of Greek and Roman antiquity.[44][45][46][47][48] Literary scholar Harold Bloom writes that "Elegies often have been used for political purposes, as a means of healing the nation".[49] A pastoral elegy uses rural imagery to address the poet's grief—a "poetic response to death" that seeks "to transmute the fact of death into an imaginatively acceptable form, to reaffirm what death has called into question—the integrity of the pastoral image of contentment." An elegy seeks, also, to "attempt to preserve the meaning of an individual's life as something of positive value when that life itself has ceased."[50][51] A typical pastoral elegy contains several features, including "a procession of mourners, the decoration of a hearse or grave, a list of flowers, the changing of the seasons, and the association of the dead person with a star or other permanent natural object."[52][53] This includes a discussion of the death, expressions of mourning, grief, anger, and consolation, and the poet's simultaneous acceptance of death's inevitability and hope for immortality.[54]

According to literary scholar James Perrin Warren, Whitman's long, musical lines rely on three important techniques—syntactic parallelism, repetition, and cataloguing.[55] Repetition is a device used by an orator or poet to lend persuasive emphasis to the sentiment, and "create a driving rhythm by the recurrence of the same sound, it can also intensify the emotion of the poem".[56] It is described as a form of parallelism that resembles a litany.[56] To achieve these techniques, Whitman employs many literary and rhetorical devices common to classical poetry and to the pastoral elegy to frame his emotional response. According to Warren, Whitman "uses anaphora, the repetition of a word or phrase at the beginning of lines; epistrophe, the repetition of the same words or phrase at the end of lines, and symploce (the combined use of anaphora and epistrophe), the repetition of both initial and terminal words.[57]

According to Raja Sharma, Whitman's use of anaphora forces the reader "to inhale several bits of text without pausing for breath, and this breathlessness contributes to the incantatory quality".[58] This sense of incantation in the poem and for the framework for the expansive lyricism that scholars have called "cataloguing".[59][60][61] Whitman's poetry features many examples of cataloguing where he both employs parallelism and repetition to build rhythm.[57] Scholar Betty Erkkila calls Whitman's cataloguing the "overarching figure of Leaves of Grass, and wrote:

His catalogues work by juxtaposition, image association, and by metonymy to suggest the interrelationship and identity of all things. By basing his verse in the single, end-stopped line at the same time that he fuses this line—through various linking devices—with the larger structure of the whole, Whitman weaves an overall pattern of unity in diversity.[62]

According to Daniel Hoffman, Whitman "is a poet whose hallmark is anaphora".[63] Hoffman describes the use of the anaphoric verse as "a poetry of beginnings" and that Whitman's use of its repetition and similarity at the inception of each line is "so necessary as the norm against which all variations and departures are measured...what follows is varied, the parallels and the ensuing words, phrases, and clauses lending the verse its delicacy, its charm, its power".[63] Further, the device allows Whitman "to vary the tempo or feeling, to build up climaxes or drop off in innuendoes"[63] Scholar Stanley Coffman analyzed Whitman's catalogue technique through the application of Ralph Waldo Emerson's comment that such lists are suggestive of the metamorphosis of "an imaginative and excited mind". According to Coffman, Emerson adds that because "the universe is the externalization of the soul, and its objects symbols, manifestations of the one reality behind them, Words which name objects also carry with them the whole sense of nature and are themselves to be understood as symbols. Thus a list of words (objects) will be effective in giving to the mind, under certain conditions, a heightened sense not only of reality but of the variety and abundance of its manifestations."[64]

Themes and symbolism

A trinity of symbols: "Lilac and star and bird twined"

Whitman's poem features three prominent motifs or images—the lilacs, a western star (Venus), and the hermit thrush—referred to as a "trinity". Biographer David S. Reynolds describes these three symbols as autobiographical.[65] Loving describes the trinity of symbols, the lilacs (the poet's perennial love for Lincoln), the fallen star (Lincoln), and the hermit thrush (death, or its chant), as brilliant.[66]

"Lilac blooming perennial"

.jpg)

According to Price and Folsom, Whitman's encounter with the lilacs in bloom in his mother's yard caused the flowers to become "viscerally bound to the memory of Lincoln's death".[14]

According to Gregory Eiselein:

Lilacs represent love, spring, life, the earthly realm, rebirth, cyclical time, a Christ figure (and thus consolation, redemption, and spiritual rebirth), a father figure, the cause of grief, and an instrument of sensual consolation. The lilacs can represent all of these meanings or none of them. They could just be lilacs.[67]

"Great star early droop'd in the western sky"

In the weeks before Lincoln's assassination, Whitman observed the planet Venus shining brightly in the evening sky. He later wrote of the observation, "Nor earth nor sky ever knew spectacles of superber beauty than some of the nights lately here. The western star, Venus, in the earlier hours of evening, has never been so large, so clear; it seems as if it told something, as if it held rapport indulgent with humanity, with us Americans"[68][69] In the poem, Whitman describes the disappearance of the star:

O powerful, western, fallen star!

O shades of night! O moody, tearful night!

O great star disappear'd! O the black murk that hides the star!(lines 7-9)

Literary scholar Patricia Lee Yongue identifies Lincoln as the falling star.[70] Further, she contrasts the dialectic of the "powerful western falling star" with a "nascent spring" and describes it as a metaphor for Lincoln's death meant to "evoke powerful, conflicting emotions in the poet which transport him back to that first and continuously remembered rebellion signaling the death of his own innocence."[70] Biographer Betsy Erkkila writes that Whitman's star is "the fallen star of America itself", and characterizes Whitman's association as "politicopoetic myth to counter Booth's cry on the night of the assassination—Sic Semper Tyrannis—and the increasingly popular image of Lincoln as a dictatorial leader bent on abrogating rather than preserving basic American liberties".[71] The star, seemingly immortal, is associated with Lincoln's vision for America—a vision of reconciliation and a national unity or identity that could only survive the president's death if Americans resolved to continue pursuing it.[72][73] However, Vendler says that the poem dismisses the idea of a personal immortality through the symbol of the star, saying: "the star sinks, and it is gone forever."[33]

"A shy and hidden bird"

In the summer of 1865, Whitman's friend, John Burroughs (1837–1921), an aspiring nature writer, had returned to Washington to his position at the Treasury department after a long vacation in the woods. Burroughs recalled that Whitman had been "deeply interested in what I tell him of the hermit thrush, and he says he largely used the information I have given him in one of his principal poems".[68] Burroughs described the song as "the finest sound in nature...perhaps more of an evening than a morning hymn...a voice of that calm, sweet solemnity one attains to in his best moments." Whitman took copious notes of his conversations with Burroughs on the subject, writing of the hermit thrush that it "sings oftener after sundown...is very secluded...likes shaded, dark places...His song is a hymn...in swamps—is very shy...never sings near the farm houses—never in the settlement—is the bird of the solemn primal woods & of Nature pure & holy."[74][75] Burroughs published an essay in May 1865 in which he described the hermit thrush as "quite a rare bird, of very shy and secluded habits" found "only in the deepest and most remote forests, usually in damp and swampy localities".[76] Loving notes that the hermit thrush was "a common bird on Whitman's native Long Island"[77] Biographer Justin Kaplan draws a connection between Whitman's notes and the lines in the poem:[75]

In the swamp in secluded recesses,

A shy and hidden bird is warbling a song.

Solitary the thrush

The hermit withdrawn to himself, avoiding the settlements,

Sings by himself a song. (lines 18–22)

According to Reynolds, Whitman's first-person narrator describes himself as "me powerless-O helpless soul of me" and identifies with the hermit thrush a "'shy and hidden bird' singing of death with a "bleeding throat'".[78] The hermit thrush is seen as an intentional alter ego for Whitman,[79] and its song as the "source of the poet's insight".[80] Miller writes that "The hermit thrush is an American bird, and Whitman made it his own in his Lincoln elegy. We might even take the 'dry grass singing' as an oblique allusion to Leaves of Grass".[81]

Scholar James Edwin Miller states that "Whitman's hermit thrush becomes the source of his reconciliation to Lincoln's death, to all death, as the "strong deliveress"[82] Killingsworth writes that "the poet retreats to the swamp to mourn the death of the beloved president to the strains of the solitary hermit thrush singing in the dark pines...the sacred places resonate with the mood of the poet, they offer renewal and revived inspiration, they return him to the rhythms of the earth with tides" and replaces the sense of time.[83]

Legacy

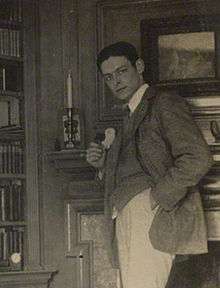

Influence on Eliot's The Waste Land

Scholars believe that T. S. Eliot (1888–1965) drew from Whitman's elegy in fashioning his poem The Waste Land (1922). In the poem, Eliot prominently mentions lilacs and April in its opening lines, and later passages about "dry grass singing" and "where the hermit-thrush sings in the pine trees."[84] Eliot told author Ford Madox Ford that Whitman and his own lines adorned by lilacs and the hermit thrush were the poems' only "good lines"[85] Cleo McNelly Kearns writes that "Whitman's poem gives us not only motifs and images of The Waste Land...but its very tone and pace, the steady andante which makes of both poems a walking meditation."[86]

While Eliot acknowledged that the passage in The Waste Land beginning "Who is the third who walks always beside you" was a reference to an early Antarctic expedition of explorer Ernest Shackleton,[87][88][89] scholars have seen connections to the appearance of Jesus to two of his disciples walking on the Road to Emmaus (Luke 24:13-35).[90][91][92] However, Alan Shucard indicates a possible link to Whitman, and a passage in the fourteenth strophe "with the knowledge of death as walking one side of me, / And the thought of death close-walking the other side of me, / And I in the middle with companions" (lines 121–123).[93]

Beginning in the 1950s, scholars and critics starting with John Peter began to question whether Eliot's poem were an elegy to "a male friend."[94] English poet and Eliot biographer Stephen Spender, who Eliot published for Faber & Faber in the 1920s, speculated it was an elegy,[95] perhaps to Jean Jules Verdenal (1890–1915), a French medical student with literary inclinations who died in 1915 during the Gallipoli Campaign, according to Miller. Eliot spent considerable amounts of time with Verdenal in exploring Paris and the surrounding area in 1910 and 1911, and the two corresponded for several years after their parting.[96] According to Miller, Eliot remembered Verdenal as "coming across the Luxembourg Garden in the late afternoon, waving a branch of lilacs,"[97] during a journey in April 1911 the two took to a garden on the outskirts of Paris. Both Eliot and Verdenal repeated the journey alone later in their lives during periods of melancholy—Verdenal in April 1912, Eliot in December 1920.[98]

Miller observes that if "we follow out all the implications of Eliot's evocation of Whitman's "Lilacs" at this critical moment in The Waste Land we might assume it has its origins, too, in a death, in a death deeply felt, the death of a beloved friend"..."But unlike the Whitman poem, Eliot's Waste Land has no retreat on the 'shores of the water,' no hermit thrush to sing its joyful carol of death."[82] He further adds that "It seems unlikely that Eliot's long poem, in the form in which it was first conceived and written, would have been possible without the precedence of Whitman's own experiments in similar forms."[82]

Musical settings

Whitman's poetry has been set by a variety of composers in Europe and the United States although critics have ranged from calling his writings "unmusical" to noting that his expansive, lyrical style and repetition mimics "the process of musical composition".[99] Jack Sullivan writes that Whitman "had an early, intuitive appreciation of vocal music, one that, as he himself acknowledged, helped shape Leaves of Grass"[100] Sullivan claims that one of the first compositions setting Whitman's poem, Charles Villiers Stanford's Elegaic Ode, Op. 21 (1884), a four-movement work scored for baritone and soprano soloists, chorus and orchestra,[101] likely had reached a wider audience during Whitman's lifetime than his poems.[102]

After World War I, Gustav Holst turned to the last section of Whitman's elegy to mourn friends killed in the war in composing his Ode to Death (1919) for chorus and orchestra. Holst saw Whitman "as a New World prophet of tolerance and internationalism as well as a new breed of mystic whose transcendentalism offered an antidote to encrusted Victorianism."[103] According to Sullivan, "Holst invests Whitman's vision of "lovely and soothing death" with luminous open chords that suggest a sense of infinite space....Holst is interested here in indeterminacy, a feeling of the infinite, not in predictability and closure."[104]

In 1936, German composer Karl Amadeus Hartmann (1905–1963) began setting a German translation of an excerpt from Whitman's poem for an intended cantata scored for an alto soloist and orchestra that was given various titles including Lamento, Kantate (trans. "Cantata"), Symphonisches Fragment (trans. "Symphonic Fragment"), and Unser Leben (trans. "Our Life").[105] The cantata contained passages from Whitman's elegy, and from three other poems.[106] Hartmann stated in correspondence that he freely adapted the poem, which he thought embraced his "generally difficult, hopeless life, although no idea will be choked with death"[107][108][109] Hartmann later incorporated his setting of the poem as the second movement titled Frühling (trans. "Spring") of a work that he designated as his First Symphony Versuch eines Requiem (trans. "Attempt at a Requiem"). Hartmann withdrew his compositions from musical performance in Germany during the Nazi era and the work was not performed until May 1948, when it was premiered in Frankfurt am Main.[110] His first symphony is seen as a protest of the Nazi regime. Hartmann's setting is compared to the intentions of Igor Stravinsky's ballet The Rite of Spring where it was not "a representation of the natural phenomenon of the season, but an expression of ritualistic violence cast in sharp relief against the fleeting tenderness and beauty of the season."[111]

American conductor Robert Shaw and his choral ensemble, the Robert Shaw Chorale, commissioned German composer Paul Hindemith to set Whitman's text to music to mourn the death of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt on April 12, 1945. Hindemith had lived in the United States during World War II. The work was titled When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd: A Requiem for those we love. Hindemith set the poem in 11 sections, scored for mezzo-soprano and baritone soloists, mixed choir (SATB), and full orchestra. It premiered on April 20, 1946, conducted by Shaw. The composition is regarded by musicologist David Neumeyer as Hindemith's "only profoundly American work."[112] and Paul Hume described it as "a work of genius and the presence of the genius presiding over its performance brought us splendor and profound and moving glory."[113] It is noted that Hindemuth incorporated a Jewish melody, Gaza, in his composition.[114]

Whitman's poem appears in the Broadway musical Street Scene (1946) which was the collaboration of composer Kurt Weill, poet and lyricist Langston Hughes, and playwright Elmer Rice. Rice adapted his 1929 Pulitzer prize-winning play of the same name for the musical. In the play, which premiered in New York City in January 1947, the poem's third stanza is recited, followed by duet, "Don't Forget The Lilac Bush", inspired by Whitman's verse. Weill received the first Tony Award for Best Original Score for this work[115][116] African-American composer George T. Walker, Jr. (born 1922) set Whitman's poem in his composition Lilacs for voice and orchestra which was awarded the 1996 Pulitzer Prize for Music.[117][118][119] The work, described as "passionate, and very American," with "a beautiful and evocative lyrical quality" using Whitman's words, was premiered by the Boston Symphony Orchestra on February 1, 1996.[117][118][120] Composer George Crumb (born 1929) set the Death Carol in his 1979 work Apparition (1979), an eight-part song cycle for soprano and amplified piano.[121]

The University of California at Berkeley commissioned American neoclassical composer Roger Sessions (1896–1985) to set the poem as a cantata to commemorate their centennial anniversary in 1964. Sessions did not finish composing the work until the 1970s, dedicating it to the memories of civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. and political figure Robert F. Kennedy, both assassinated in 1968.[122][123] Sessions first became acquainted with Leaves of Grass in 1921 and began setting the poem as a reaction to the death of his friend, George Bartlett, although none of the sketches from that early attempt survive. He returned to the text almost fifty years later, composing a work scored for soprano, contralto, and baritone soloists, mixed chorus and orchestra. The music is described as responding "wonderfully both to the Biblical majesty and musical fluidity of Whitman's poetry, and here to, in the evocation of the gray-brown bird singing from the swamp and of the over-mastering scent of the lilacs, he gives us one of the century's great love letters to Nature."[124]

In 2004, working on a commission from the Brooklyn Philharmonic, the American composer Jennifer Higdon adapted the poem to music for solo baritone and orchestra titled Dooryard Bloom. The piece was first performed on April 16, 2005 by the baritone Nmon Ford and the Brooklyn Philharmonic under the conductor Michael Christie.[125][126]

See also

References

- ↑ Gutman 1998.

- ↑ Miller 1962, p. 155.

- ↑ Kaplan 1980, p. 187.

- ↑ Loving 1999, p. 414.

- 1 2 Kaplan 1980.

- ↑ Callow 1992, p. 232.

- ↑ Reynolds 1995, p. 340.

- ↑ Loving 1999, p. 283.

- ↑ Callow 1992, p. 293.

- ↑ Peck 2015, p. 64.

- ↑ Whitman 1961, p. 1:68–70.

- ↑ Loving 1975.

- ↑ Loving 1999, p. 281–283.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Price, Kenneth & Folsom 2005, p. 91.

- ↑ Whitman 1882, p. 310.

- ↑ Swanson 2006, p. 213.

- ↑ Sandburg 1936, p. 394.

- ↑ Loving 1999, p. 289.

- ↑ Whitman & Eckler 1865, p. 69.

- ↑ Whitman 1865, p. 3–11.

- 1 2 Whitman 1867.

- ↑ Whitman 1980, p. xvii.

- 1 2 Price, Kenneth & Folsom 2005, p. 98.

- ↑ Whitman 1980, p. lxii,lxvii.

- ↑ Whitman 1871–1872, p. 32–40.

- ↑ Whitman 1881.

- ↑ Whitman 1891–1892, p. 255–262.

- ↑ Harvard.

- ↑ Norton.

- ↑ Parini 2006, p. 187–194.

- ↑ Parini 1995, p. 217–224.

- ↑ Greene 2012, p. 398,911.

- 1 2 3 4 Vendler 2006, p. 191–206.

- ↑ Rowe 1997, p. 134–135.

- 1 2 Rowe 1997, p. 149,n.7.

- ↑ Whitman 1871–1872.

- ↑ Whitman 1881, p. 255–262.

- ↑ Loving 1999, p. 100.

- ↑ Rugoff 2000, p. 134–135.

- ↑ Miller 1962.

- ↑ Drum 1911.

- ↑ Casanowicz 1901–1906.

- ↑ Boulton 1953.

- ↑ Parini 2006, p. 129–130.

- ↑ Hinz 1972, p. 35–54.

- ↑ Chase 1955, p. 140-145.

- ↑ Adams 1957, p. 479-487.

- ↑ Ramazani 1994.

- ↑ Bloom 1999, p. 91.

- ↑ Shore 1985, p. 86–87.

- ↑ Hamilton 1990, p. 618.

- ↑ Zeiger 2006, p. 243.

- ↑ Cuddon 2012.

- ↑ Zeiger 2006.

- ↑ Warren 2009, p. 377–392, at 383.

- 1 2 Anaphora.

- 1 2 Warren 2009, p. 377–392.

- ↑ Sharma.

- ↑ Sharma, p. 40–41.

- ↑ Magnus 1989, p. 137ff.

- ↑ Hollander 2006, p. 183.

- ↑ Erkkila 1989, p. 88.

- 1 2 3 Hoffmann 1994, p. 11-12.

- ↑ Coffman 1954, p. 225–232.

- ↑ Reynolds 1995.

- ↑ Loving 1999, p. 288.

- ↑ Eiselein.

- 1 2 Reynolds 1995, p. 445.

- ↑ Whitman 1882–1883, p. 65–66.

- 1 2 Yongue 1984, p. 12–20.

- ↑ Erkkila 1989, p. 228–229.

- ↑ Rowe 1997, p. 159.

- ↑ Mack 2002, p. 125.

- ↑ Whitman (Notebooks 2:766)

- 1 2 Kaplan 1980, p. 307–310.

- ↑ Burroughs 1895, p. 1:223.

- ↑ Loving 1999, p. 289,n.85.

- ↑ Reynolds 1995, p. 444.

- ↑ Aspiz 1985, p. 216–233,227.

- ↑ Rugoff 1985, p. 257–271.

- ↑ Miller 2005, p. 418.

- 1 2 3 Miller 2005, p. 419.

- ↑ Killingsworth, M. Jimmie in Kummings, 311-325, 322

- ↑ Eliot 1922, p. 355,357.

- ↑ Eliot 1971, p. 129.

- ↑ Kearns 1986, p. 150.

- ↑ Eliot 1922, lines 360–366.

- ↑ Ackerley 1984, p. 514.

- ↑ Rainey 2005, p. 117–118.

- ↑ Eliot 1974, p. 147–148.

- ↑ Miller 1977, p. 113.

- ↑ Bentley 1990, p. 179,183.

- ↑ Shucard 1998, p. 203.

- ↑ Peter 1952, p. 242–66.

- ↑ Miller 2005, p. 135.

- ↑ Miller 2005, p. 130–135.

- ↑ Miller 2005, p. 133.

- ↑ Miller 2005, p. 7–8,133.

- ↑ Sullivan 1999, p. 95ff.

- ↑ Sullivan 1999, p. 97.

- ↑ Town 2003, p. 73–102, at 78.

- ↑ Sullivan 1999, p. 98.

- ↑ Sullivan 1999, p. 116.

- ↑ Sullivan 1999, p. 118.

- ↑ Chapman 2006.

- ↑ Chapman 2006, p. 47.

- ↑ Chapman 2006, p. 36–37.

- ↑ McCredie 1982, p. 57.

- ↑ Kater 2000, p. 90.

- ↑ Chapman 2006, p. 45.

- ↑ Chapman 2006, p. 3.

- ↑ Sullivan 1999, p. 122.

- ↑ Noss 1989, p. 188.

- ↑ Chapman 2006, p. 40,fn.10.

- ↑ Sullivan 1999, p. 119–122.

- ↑ Hinton 2012, p. 381–385.

- 1 2 Fischer & Fischer 2001, p. xlvi.

- 1 2 Fischer 1988, p. 278.

- ↑ Walker 2009, p. 228.

- ↑ Brennan & Clarage 1999, p. 451.

- ↑ Clifton 2008, p. 40.

- ↑ Steinberg 2005, p. 252–255.

- ↑ Rugoff 1985, p. 257–271, at 270.

- ↑ Steinberg 2005, p. 346–347.

- ↑ Higdon, Jennifer (January 15, 2006). "Jennifer Higdon's 'Dooryard Bloom'". NPR. Retrieved August 14, 2015.

- ↑ Kozinn, Allan (April 18, 2005). "A Celebration of Brooklyn, via Whitman". The New York Times. Retrieved August 14, 2015.

Bibliography

Books

- Aspiz, Harold (1985). LeMaster, J. R.; Kummings, Donald D. Kummings, eds. "Science and Pseudoscience" in Walt Whitman: An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge.

- Bentley, Joseph (1990). Reading "The Waste Land": Modernism and the Limits of Interpretation. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

- Bloom, Harold, ed. (1999). Walt Whitman. Broomall, PA: Chelsea House Publishers.

- Boulton, Marjories (1953). Anatomy of Poetry. London: Routledge & Kegan.

- Brennan, Elizabeth A.; Clarage, Elizabeth C. (1999). Who's Who of Pulitzer Prize Winners. ISBN 978-1-57356-111-2.

- Burroughs, John (1895). "The Return of the Birds" in The Writings of John Burroughs. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Callow, Philip (1992). From Noon to Starry Night: A Life of Walt Whitman. Chikago: Ivan R. Dee.

- Casanowicz, I.M. (1901–1906). "Parallelism in Hebrew Poetry" in The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk and Wagnalls.

- Chapman, David Allen (2006). "Ich Sitze und Schaue" from Genesis, Evolution, and Interpretation of K. A. Hartmann's First Symphony (PDF). Athens, GA: University of Georgia (thesis).

- Chase, Richard (1955). Walt Whitman Reconsidered. New York: William Sloan.

- Clifton, Keith E. (2008). Recent American Art Song: A Guide. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press.

- Coffman, Stanley K. (1954). "'Crossing Brooklyn Ferry': A Note on the Catalogue Technique in Whitman's Poetry", Modern Philology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cuddon, J. A. (2012). Kastan, David Scott, ed. "Elegy" in Dictionary of Literary Terms and Literary Theory. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

- Drum, Walter (1911). "Parallelism" in The Catholic Encyclopedia. 11. New York: Robert Appleton.

- Eiselein, Gregory. Literature and Humanitarian Reform in the Civil War Era.

- Eliot, T(homas) S(tearns) (1922). The Waste Land. New York: Horace Liveright.

- Eliot, T(homas) S(tearns) (1971). Eliot, Valerie, ed. The Waste Land: A Facsimile and Transcript of the Original Drafts. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- Eliot, T(homas) S(tearns) (1974). Eliot, Valerie, ed. The Waste Land: A Facsimile and Transcript of the Original Drafts, Including the Annotations of Ezra Pound. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Erkkila, Betty (1989). Whitman the Political Poet. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press.

- Fischer, Heinz Dietrich (1988). The Pulitzer Prize archive. ISBN 978-3-598-30170-4.

- Fischer, Heinz Dietrich; Fischer, Erika J. (2001). Musical Composition Awards 1943-1999. ISBN 978-3-598-30185-8.

- Greene, Roland, ed. (2012). "Elegy" and "Narrative Poetry" in The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics (4 ed.). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Gutman, Huck (1998). LeMaster, J. R.; Kummings, Donald D. Kummings, eds. Commentary – Selected Criticism: "Drum-Taps" (1865) on Walt Whitman: An Encyclopedia. New York: Garland Publishing.

- Hamilton, A. C. (1990). The Spencer Encyclopedia. Toronto/Buffalo: University of Toronto Press.

- Hinton, Stephen (2012). Weill's Musical Theater: Stages of Reform. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Hoffmann, Daniel (1994). Sill, Geoffrey M., ed. "Hankering, Gross, Mystical, Nude": Whitman's "Self" and the American Tradition" in Walt Whitman of Mickle Street: A Centennial Collection. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press.

- Hollander, John (2006). Bloom, Harold, ed. "Whitman's Difficult Availability" in Bloom's Modern Critical Views: Walt Whitman. New York: Chelsea House.

- Kaplan, Justin (1980). Walt Whitman: A Life. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Kater, Michael H. (2000). Composers of the Nazi Era: Eight Portraits. New York: Oxford University.

- Kearns, Cleo McNelly (1986). Bloom, Harold, ed. Realism, Politics, and Literary Persona in The Waste Land. New York: Chelsea House.

- Loving, Jerome (1999). Walt Whitman: The Song of Himself. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Loving, Jerome M. (1975). Civil War Letters of George Washington Whitman. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Mack, Stephen John (2002). The Pragmatic Whitman: Reimagining American Democracy. Iowa City: Iowa: University of Iowa Press.

- Magnus, Laury (1989). The Track of the Repetend: Syntactic and Lexical Repetition in Modern Poetry. Brooklyn: AMS Press.

- McCredie, Andres (1982). Karl Amadeus Hartmann: Thematic Catalogue of His Works. New York: C.F. Peters.

- Miller, James E. (1962). Walt Whitman. New York: Twayne Publishers.

- Miller, James E. (1977). T. S. Eliot's Personal Waste Land: Exorcism of the Demons. State College, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Miller, James Edwin (2005). T.S. Eliot: The Making of an American poet, 1888-1922. State College, Pennsylvania: Penn State Press.

- Noss, Luther (1989). Paul Hindemuth in the United States. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

- Olmstead, Andrew (2008). Roger Sessions: A Biography. New York: Routledge.

- Parini, Jay, ed. (1995). The Columbia Anthology of American Poetry. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Parini, Jay, ed. (2006). The Wadsworth Anthology of Poetry. Boston: Thompson Wadsworth.

- Peck, Garrett (2015). Walt Whitman in Washington, D.C.: The Civil War and America's Great Poet. Charleston, SC: The History Press. ISBN 9781626199736.

- Price, Kenneth; Folsom, Ed, eds. (2005). Re-Scripting Walt Whitman: An Introduction to His Life and Work. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Rainey, Lawrence S., ed. (2005). The Annotated Waste Land with Eliot's Contemporary Prose. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Ramazani, Jahan (1994). Poetry of Mourning: The Modern Elegy from Hardy to Heaney. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Reynolds, David S. (1995). Walt Whitman's America: A Cultural Biography. New York: Vintage Books.

- Rowe, John Carlos (1997). At Emerson's Tomb: The Politics of Classic American Literature. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Rugoff, Kathy (2000). Kramer, Lawrence, ed. "Three American Requiems: Contemplating 'When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd'" in Walt Whitman and Modern Music: War, Desire and the Trials of Nationhood. 1. New York: Garland Press.

- Rugoff, Kathy (1985). LeMaster, J. R.; Kummings, Donald D. Kummings, eds. "Opera and Other Kinds of Music" in Walt Whitman: An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge.

- Sandburg, Carl (1936). Abraham Lincoln: The War Years IV. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

- Sharma, Raja. Walt Whitman's Poetry-An Analytical Approach.

- Shore, David R. (1985). Spenser and the Poetics of Pastoral: A Study of the World of Colin Clout. Montreal: McGill University Press.

- Shucard, Alan (1985). LeMaster, J. R.; Kummings, Donald D. Kummings, eds. "Eliot, T.S. (1888-1965)" in Walt Whitman: An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge.

- Steinberg, Michael (2005). Choral Masterworks: A Listener's Guide. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press.

- Sullivan, Jack (1999). Manhunt: New World Symphonies: How American Culture Changed European Music. ISBN 978-0-300-07231-0.

- Swanson, James (2006). Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln's Killer. New York: HarperCollins.

- Town, Stephen (2003). Adams, Byron; Wells, Robin, eds. "'Full of fresh thoughts: Vaughn Williams, Whitman, and the Genesis of A Sea Symphony", in Adams, Byron, and Wells, Robin (editors), Vaughan Williams Essays. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing.

- Vendler, Helen (2006). "Poetry and the Meditation of Value: Whitman on Lincoln", in Bloom, Harold. Bloom's Modern Critical Views: Walt Whitman. New York: Chelsea House.

- Walker, George (2009). Reminiscences of an American Composer and Pianist. ISBN 978-0-8108-6940-0.

- Warren, James Perrin (2009). Kummings, Donald D., ed. "Style" in A Companion to Walt Whitman. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

- Whitman, Walt (1865). "Hush'd Be the Camps To-Day" in Drum-Taps. Brooklyn: Peter Eckler.

- Whitman, Walt (1865). Sequel to Drum-Taps. When Lilacs Last in the Door-Yard Bloom'd and other poems. Washington: Gibson Brothers.

- Whitman, Walt (1867). Price, Kenneth; Folsom, Ed, eds. "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd" in Leaves of Grass. New York: William E. Chapin.

- Whitman, Walt (1871–1872). "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd" in Leaves of Grass. New York: J.S. Redfield.

- Whitman, Walt (1881). "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd" in Leaves of Grass.

- Whitman, Walt (1881). "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd" in Leaves of Grass (7 ed.). Boston: James R. Osgood.

- Whitman, Walt (1882–1883). "The Weather.—Does it sympathize with these times?" from Specimen Days and Collect.

- Whitman, Walt (1882). Death of Abraham Lincoln. Lecture deliver'd in New York, April 14, 1879—in Philadelphia, '80—in Boston, '81 in Specimen Days & Collect. Philadelphia: Rees Welsh & Company.

- Whitman, Walt (1891–1892). Leaves of Grass. Philadelphia: David McKay.

- Whitman, Walt (1961). Miller, Edwin Haviland, ed. The Correspondence. 1. New York: New York University Press.

- Whitman, Walt (1980). Bradley; Scully, eds. Leaves of Grass: A Textual Variorum of the Printed Poems. 1. New York: New York University Press.

- Zeiger, Melissa (2006). Kastan, David Scott, ed. "Elegy" in The Oxford Encyclopedia of British Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- The Harvard Classics. 3. 1909–1914.

- English Poetry from Tennyson to Whitman in The Norton Anthology of American Literature. New York: W. W. Norton & Co.

Journals

- Ackerley, C. J. (1984). "Eliot's The Waste Land and Shackleton's South". Notes & Queries.

- Adams, Richard P. (1957). "Whitman's 'Lilacs' and the Tradition of Pastoral Elegy". Bucknell Review.

- Hinz, Evelyn J. (1972). "Whitman's 'Lilacs': The Power of Elegy". Bucknell Review.

- Peter, John (1952). "A New Interpretation of The Waste Land". Essays in Criticism.

- Yongue, Patricia Lee (1984). "Violence in Whitman's 'When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd'". Walt Whitman Quarterly Review.

Online sources

- "Poetic Technique: Anaphora". American Academy of Poets.

Further reading

- Max Cavitch, American Elegy: The Poetry of Mourning from the Puritans to Whitman (University of Minnesota Press, 2007). ISBN 0-8166-4893-X

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- The Walt Whitman Archive

- "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd" at the Poetry Foundation website

- "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd" from The Harvard Classics on Bartleby.com