Early life and career of Abraham Lincoln

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

President of the United States First term Second term Assassination and legacy

|

||

Abraham Lincoln was born on February 12, 1809, in a one-room log cabin at Sinking Spring farm, south of Hodgenville, in Hardin County, Kentucky. After a land title dispute forced the family to leave, they relocated to Knob Creek farm, eight miles to the north. By 1814 Thomas Lincoln, Abraham's father, had lost most of his land in Kentucky in legal disputes over land titles. In 1816 Thomas and Nancy Lincoln, their nine-year-old daughter, Sarah, and seven-year-old Abraham moved to Indiana, where they settled in Hurricane Township, Perry County, Indiana. (Their land became part of Spencer County, Indiana, when it was formed in 1818.)

Abraham spent his formative years, from the age of 7 to 21, on the family farm in Southern Indiana. As was common on the frontier, Lincoln received a meager formal education, the aggregate of which may have been less than twelve months. However, Lincoln continued to learn on his own from life experiences and through reading and reciting what he had read or heard from others. In 1818, two years after their arrival in Indiana, nine-year-old Lincoln lost his birth mother, Nancy, who died after a brief illness. Thomas returned to Kentucky the following year and married Sarah Bush Johnson. Abraham's new step-mother and her three children joined the Lincoln family in Indiana in 1819. A second tragedy befell the family in 1828, when Abraham's sister, Sarah, died in childbirth.

In 1830 twenty-one-year-old Abraham joined his extended family in a move to Illinois. After helping his father establish a farm in Macon County, Illinois, Lincoln set out on his own. Lincoln worked as a boatman, store clerk, surveyor, militia soldier, and became a lawyer in Illinois. He was elected to the Illinois Legislature in 1834, and was reelected in 1836, 1838, 1840, and 1844. In 1842, Lincoln married Mary Todd; the couple had four sons. In addition to his law career, Lincoln continued his involvement in politics, serving in the United States House of Representatives from Illinois in 1846. He was elected president of the United States in 1860.

Ancestry

Lincoln's first known ancestor in America was Samuel Lincoln, who migrated from England to Hingham, Massachusetts, in 1638. Samuel's son, Mordecai, remained in Massachusetts, but Samuel's grandson, who was also named Mordecai, began the family's western migration. John Lincoln, Samuel's great-grandson, continued the westward journey. Born in New Jersey, John moved to Pennsylvania, then brought his family to Virginia.[1] John's son, Captain Abraham Lincoln, who earned that rank for his service in the Virginia militia, was the future president's paternal grandfather and namesake. Born in Pennsylvania, he moved with his father and other family members to Virginia's Shenandoah Valley around 1766. The family settled near Linville Creek, in Augusta County, now Rockingham County, Virginia. Captain Lincoln bought the Virginia property from his father in 1773.

Thomas Lincoln, the future president's father, was Captain Lincoln's son. Thomas was born in Virginia and moved west to Jefferson County, Kentucky, with his father, mother, and siblings in the 1780s, when he was about five years old.[2] In 1786, at the age of forty-two, Captain Abraham was killed in an Indian ambush while working his field in Kentucky. Eight-year-old Thomas witnessed his father's murder and may have ended up a victim if his brother, Mordecai, had not shot the attacker.[3] After Captain Lincoln's death, Thomas's mother moved to Washington County, Kentucky, while Thomas worked at odd jobs in several Kentucky locations. Thomas also spent a year working in Tennessee, before settling with members of his family in Hardin County, Kentucky, in the early 1800s.[4]

The identity of Lincoln's maternal grandfather is unclear. In a conversation with William Herndon, Lincoln's law partner and one of his biographers, the president implied that his grandfather was "a Virginia planter or large farmer", but did not identify him.[5] Lincoln felt that it was from this aristocratic grandfather that he had inherited "his power of analysis, his logic, his mental activity, his ambition, and all the qualities that distinguished him from the other members and descendants of the Hanks family."[6] Lincoln's maternal grandmother, Lucy Shipley Hanks, migrated to Kentucky, with her daughter, Nancy. The debate continues over whether Lincoln's mother, Nancy, was born out of wedlock. Lucy and Nancy resided with Lucy's older sister, Rachael Shipley Berry, and her husband, Richard Berry Sr., in Washington County, Kentucky. Nancy is believed to have remained with the Berry family after her mother's marriage to Henry Sparrow, which took place several years after the women arrived in Kentucky.[5][7] The Berry home was about a mile and a half from the home of Thomas Lincoln's mother; the families were neighbors for seventeen years. It was during this time when Thomas met Nancy.[8] Thomas Lincoln and Nancy Hanks were married on June 12, 1806, at the Beech Fork settlement in Washington County, Kentucky. The Lincolns moved to Elizabethtown, Kentucky, following their marriage.[9]

Unproven rumors

Biographers have rejected numerous rumors about Lincoln's paternity. According to historian William E. Barton, one of these rumors began circulating in 1861 "in various forms in several sections of the South" that Lincoln's biological father was Abraham Enloe, a resident of Rutherford County, North Carolina, who died in that same year. However, Barton dismissed the rumors as "false from beginning to end."[10] Enloe publicly denied his connection to Lincoln, but is reported to have privately confirmed it.[11] The Bostic Lincoln Center in Bostic, North Carolina, also claims that Abraham Lincoln was born in Rutherford County, North Carolina, and argues the case that Nancy Hanks had an illegitimate child while she was working for the Enlow family.[12]

Rumors of Lincoln's ethnic and racial heritage were also circulated, especially after he entered national politics. Citing Chauncey Burr's Catechism, which references a "pamphlet by a western author adducing evidence", David J. Jacobson has suggested Lincoln was "part Negro",[13] but the claim is unproven. Lincoln also received mail that called him "a negro"[14] and a "mulatto".[14]

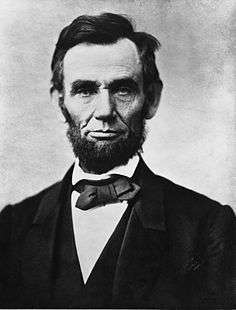

Lincoln's appearance

Lincoln was described as "ungainly" and "gawky" as a youth.[15] Tall for his age, Lincoln was strong and athletic as a teenager. He was a good wrestler, participated in jumping, throwing, and local footraces, and "was almost always victorious."[16] His stepmother remarked that he cared little for clothing.[17] Lincoln dressed as an ordinary boy from a poor, backwoods family, with a gap between his shoes, socks, and pants that often exposed six or more inches of his shin. His lack of interest in his personal attire continued as an adult. When Lincoln lived in New Salem, Illinois, he frequently appeared with a single suspender, and no vest or coat.[18]

In 1831, the year after he left Indiana, Lincoln was described as six feet three or four inches tall, weighing 210 pounds, and had a ruddy complexion.[15] Later descriptions included Lincoln's dark hair and dark complexion, which were also evident in photographs taken during his tenure as president of the United States. William H. Herndon described Lincoln as having "very dark skin";[19] his cheeks as "leathery and saffron-colored"; a "sallow" complexion;[19] and "his hair was dark, almost black".[19] Lincoln described himself around 1838–39 as "black"[20] and his complexion in 1859 as "dark"[21] Lincoln's detractors also remarked on his appearance. For example, during the American Civil War the Charleston, South Carolina Mercury described him as having "the dirtiest complexion" and asked "Faugh! After him what white man would be President?"[22]

Early years (1809–1831)

During his later years, Lincoln was reluctant to discuss his origins. He viewed himself as a self-made man, and may have also found it difficult to confront the untimely deaths of his mother and his sister.[23] However, around the time of his nomination as a candidate for president of the United States, Lincoln provided two brief biographical sketches in response to two inquiries that provide a glimpse of youth in Kentucky and Indiana. One request for a campaign biography came from his friend and fellow Illinois Republican, Jesse W. Fell, in 1859; the other request came from John Locke Scripps, a journalist for the Chicago Press and Tribune.[24] In Lincoln's response Scripps, he summed up his early life in a quote from Thomas Gray's Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard, as "the short and simple annals of the poor."[25] Additional details of Lincoln's early life appeared after his death in 1865, when William Herndon began collecting letters and interviews from Lincoln's friends, family, and acquaintances. Herndon published his collected materials in Herndon's Lincoln: The True Story of a Great Life (1889). Although Herndon's work is often challenged, historian David Herbert Donald argues that they "have largely shaped current beliefs" about Lincoln's early life in Kentucky, Indiana, and his early days in Illinois.[26][27]

Early life in Kentucky (1809–1816)

Thomas and Nancy Hanks Lincoln became the parents of three children during their years in Kentucky. Sarah was born on February 10, 1807; Abraham, on February 12, 1809; and another son, Thomas, who died in infancy.[28]

In 1808, Thomas, Nancy, and their daughter, Sarah, moved from Elizabethtown to the Sinking Spring farm, on Nolen Creek, the near Hodgen's Mill, in Hardin County, Kentucky. (The farm is part of the Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historic Site in present-day LaRue County, Kentucky.) Abraham was born at the farm in 1809. Due to a land title dispute, the family lived at the farm only two more years before they were forced to move. Thomas continued legal action in court, but lost the case in 1815. Kentucky's survey methods, which used a system of metes and bounds to identify and describe land descriptions, proved to be unreliable when the natural features of the land changed. This issue, compounded by confusion over previous land grants and purchase agreements, caused continual legal disputes over land ownership in Kentucky.[29][30] In 1811, the family relocated to Knob Creek farm, now a part of the Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historic Site, eight miles to the north.[31] Situated in a valley of the Rolling Fork River, it had some of the best farmland in the area. Lincoln's earliest recollections of his boyhood are from this farm.[32] In 1815 a claimant in another land dispute sought to eject the Lincoln family from the Knob Creek farm.[30]

Years later, after Lincoln became a national political figure, reporters and storytellers often exaggerated his family's poverty and the obscurity of his birth. Lincoln's family circumstances were not unusual for pioneer families at that time. Thomas Lincoln was a farmer, carpenter, and landowner in the Kentucky backcountry. He had purchased the Sinking Spring Farm, which comprised 348.5 acres, in December 1808 for $200, but lost his cash investment and the improvements he had made on the farm in a legal dispute over the land title. Thomas acquired title to the Knob Creek farm on 230 acres of land, but the family was forced to leave it after others claimed a prior title to the land.[30] Of the 816.5 acres that Thomas held in Kentucky, he lost all but 200 acres in land title disputes. By 1816 Thomas was frustrated over the lack of security provided by Kentucky courts. He sold the remaining land he held in Kentucky in 1814, and began planning a move to Indiana, where the land survey process was more reliable and the ability for an individual to retain land titles was more secure.[33]

In 1860 Lincoln stated that the family's move to Indiana in 1816 was "partly on account of slavery; but chiefly on account of the difficulty in land titles in Kentucky."[34] Historians support Lincoln's assertion that the two major reasons for the family's migration to Indiana were most likely due to the problem with securing land titles in Kentucky and the issue of slavery.[30] In the Indiana Territory, once a part of the Old Northwest Territory, the federal government owned the territorial land, which had been surveyed into sections to make it easier to describe in land claims. As a result, the survey method used in Indiana caused fewer ownership problems and helped Indiana attract new settlers. In addition, when Indiana became a state in 1816, the state constitution prohibited slavery as well as involuntary servitude. Although slaves with earlier indentures still resided within the state, illegal slavery ended within the first decade of statehood.[35]

Early religious beliefs

Lincoln never joined a religious congregation;[36] however, his father, mother, sister, and stepmother were all Baptists. Abraham's parents, Thomas and Nancy Lincoln, belonged to Little Mount Baptist Church, a Baptist congregation in Kentucky that had split from a larger church in 1808 because its members refused to support slavery.[37] Through their membership in this anti-slavery church, Thomas and Nancy exposed Abraham and Sarah to anti-slavery sentiment at a very young age. After settling in Indiana, Lincoln's parents continued their Baptist church membership, joining the Big Pigeon Baptist Church in 1823. When the Lincoln family left Indiana for Illinois in 1830, Thomas and his second wife, Sally, were members in good standing at the Little Pigeon Baptist Church.[38]

Sally Lincoln recalled in 1865 that her stepson, Abraham, "had no particular religion"[39] and did not talk about it much. She also remembered that he often read the Bible and occasionally attended church services.[39] Matilda Johnston Hall Moore, Lincoln's stepsister, explained in an 1865 interview how Lincoln would read the Bible to his siblings and join them in singing hymns after his parents had gone to church. Other family members and friends who knew Lincoln during his a youth in Indiana recalled that he would often get up on a stump, gather children, friends, and coworkers around him, and repeat a sermon he had heard the previous week to the amusement of the locals, especially the children.[40]

Indiana years (1816–1830)

Lincoln spent fourteen of his formative years, or roughly one-quarter of his life, from the age of seven to twenty-one in Indiana.[41] In 1816, Thomas and Nancy Lincoln, their nine-year-old daughter, Sarah, and seven-year-old Abraham moved to Indiana. They settled on land in an "unbroken forest"[42] in Hurricane Township, Perry County, Indiana. The Lincoln property lay on land ceded to the United States government as part of treaties with the Piankeshaw and Delaware people in 1804. In 1818 the Indiana General Assembly created Spencer County, Indiana, from portions of Warrick and Perry counties, which included the Lincoln farm.[43][44]

The move to Indiana had been planned for at least several months. Thomas visited Indiana Territory in 1816 to select a site and mark his claim, then returned to Kentucky and brought his family to Indiana sometime between November 11 and December 20, 1816, about the same time that Indiana became a state.[45][46] However, Thomas Lincoln did not begin the formal process to purchase 160 acres of land until October 15, 1817, when he filed a claim at the land office in Vincennes, Indiana, for property identified as "the southwest quarter of Section 32, Township 4 South, Range 5 West".[47][48]

More recent scholarship on Thomas Lincoln has revised previous characterizations of him as a "shiftless drifter".[49] Documentary evidence suggests he was a typical pioneer farmer of his time. The move to Indiana established his family in a state that prohibited slavery, and they lived in an area that yielded timber to construct a cabin, adequate soil to grow crops that fed the family, and water access to markets along the Ohio River.[50][51] Thomas owned horses and livestock, paid taxes, acquired farmland, served the county when was necessary, and maintained his standing in the local Baptist church. Despite some financial challenges, which involved relinquishing some acreage to pay for debts or to purchase other land, he obtained clear title to 80 acres of land in Spencer County, on June 5, 1827. By 1830, before the family moved to Illinois, Thomas had acquired twenty acres of land adjacent to his property.[52]

Abraham, who became skilled with an axe, helped his father clear their Indiana land. Recalling his boyhood in Indiana, Lincoln remarked that from the time of his arrival in 1816, he "was almost constantly handling that most useful instrument."[53] Once the land had been cleared, the family raised hogs and corn on their farm, which was typical for Indiana settlers at that time. Thomas Lincoln also continued to work as a cabinetmaker and carpenter.[54] Within a year of the family's arrival in Indiana, Thomas had claimed title to 160 acres of Indiana land and paid $80, a quarter of its total purchase price of $320. The Lincolns and others, many of whom came from Kentucky, settled in what became known the Little Pigeon Creek Community,[55] about one hundred miles from the Lincoln farm at Knob Creek in Kentucky. By the time Abraham had reached age thirteen, nine families with forty-nine children under the age of seventeen were living within a mile of the Lincoln homestead.[56]

Tragedy struck the family on October 5, 1818, when Nancy Lincoln died of milk sickness, an illness caused by drinking contaminated milk from cows who fed on Ageratina altissima (white snakeroot).[57] Abraham was nine years old; his sister, Sarah, was eleven. After Nancy's death the household consisted of Thomas, aged forty; Sarah, Abraham, and Dennis Friend Hanks, an orphaned nineteen-year-old cousin of Nancy Lincoln.[58][59] In 1819 Thomas left Sarah, Abraham, and Dennis Hanks at the farm in Indiana and returned to Kentucky. On December 2, 1819, Lincoln's father married Sarah "Sally" Bush Johnston. a widow with three children from Elizabethtown, Kentucky.[60][61] Ten-year-old Abe quickly bonded with his new stepmother, who raised her two young stepchildren as her own. Describing her in 1860, Lincoln remarked that she was "a good and kind mother" to him.[62]

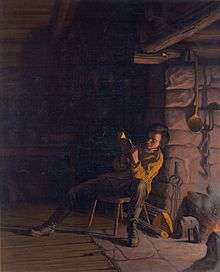

Sally encouraged Lincoln's eagerness to learn and desire to read, and shared her own collection of books with him.[47] Years later she compared Lincoln to her own son, John D. Johnston: "Both were good boys, but I must say — both now being dead that Abe was the best boy I ever saw or ever expect to see." In an interview with William Herndon following Lincoln's death in 1865, Sally Lincoln described her stepson as dutiful and kind, especially to animals and children, and cooperative and uncomplaining. She also remembered him as a "moderate" eater, who was not picky about what he ate, and enjoyed good health.[63] In pioneer-era Indiana, where hunting and fishing were typical pursuits, Thomas and Abraham did not appear to have enjoyed them. Abraham later admitted that he had shot and killed only a single wild turkey. Apparently, he opposed killing animals, even for food, but occasionally participated in bear hunts, when the bears threatened settlers' farms and communities.[64]

In 1828 another tragedy struck the Lincoln family. Lincoln's older sister, Sarah, who had married Aaron Grigsby on August 2, 1826, died in childbirth on January 20, 1828,[65] when she was twenty-one years old. Little is known about Nancy Hanks Lincoln or Abraham's sister. Neighbors who were interviewed by William Herndon agreed that they were intelligent, but gave contradictory descriptions of their physical appearances.[66] Lincoln spoke very little about either woman. Herndon had to rely on testimony from a cousin, Dennis Hanks, to get an adequate description of Sarah. Those who knew Lincoln as a teenager later recalled him being deeply distraught by his sister's death, and an active participant in a feud with the Grigsby family that erupted afterwards.[67]

First trip to New Orleans (1828)

Possibly looking for a diversion from the sorrow of his sister's death, nineteen-year-old Abraham made a flatboat trip to New Orleans in the spring of 1828.[68] Lincoln and Allen Gentry, the son of James Gentry, owner of a local store near the Lincoln family's homestead, began their trip along the Ohio River at Gentry's Landing, near Rockport, Indiana. En route to Louisiana, Lincoln and Gentry were attacked by several African American men who attempted to take their cargo, but the two successfully defended their boat and repelled their attackers.[69][70] Upon their arrival in New Orleans, they sold their cargo, which was owned by Gentry's father, then explored the city. With its considerable slave presence and active slave market, it is probable that Lincoln witnessed a slave auction, and it may have left an indelible impression on him. (Congress outlawed the importation of slaves in 1808, but the slave trade continued to flourish within the United States.[70]) How much of New Orleans Lincoln saw or experienced is open to speculation. Whether he actually witnessed a slave auction at that time, or on a later trip to New Orleans, his first visit to the Deep South exposed him to new experiences, including the cultural diversity of New Orleans and a return trip to Indiana aboard a steamboat.[70][71]

Education

In 1858, when responding to a questionnaire sent to former members of Congress, Lincoln described his education as "defective".[72] In 1860, shortly after his nomination for U.S. president, Lincoln apologized for and regretted his limited formal education. Lincoln was self-educated. His formal schooling intermittent, the aggregate of which may have amounted to less than twelve months. He never attended college, but Lincoln retained a lifelong interest in learning.[73][74] In a September 1865 interview with William Herndon, Lincoln's stepmother described Abraham as a studious boy who read constantly, listened intently to others, and had a deep interest in learning. Lincoln continued reading as a means of self improvement as an adult, studying English grammar in his early twenties and mastering Euclid after he became a member of Congress.[75]

Dennis Hanks, a cousin of Lincoln's mother, Nancy, claimed he gave Lincoln "his first lesson in spelling—reading and writing" and boasted, "I taught Abe to write with a buzzards quill which I killed with a rifle and having made a pen—put Abes hand in mind [sic] and moving his fingers by my hand to give him the idea of how to write."[76] Hanks, who was ten years older than Lincoln and "only marginally literate",[76] may have helped Lincoln with his studies when he was very young, but Lincoln soon advanced beyond Hanks's abilities as a teacher.[77]

Abraham, aged six, and his sister Sarah began their education in Kentucky, where they attended a subscription school about two miles north of their home on Knob Creek. Classes were held only a few months during the year.[78][79] In 1816, when they arrived in Indiana, there were no schools in the area, so Abraham and his sister continued their studies at home until the first school at Little Pigeon Creek was established around 1819, "about a mile and a quarter south of the Lincoln farm."[80] In the 1820s, educational opportunities for pioneer children, including Lincoln, were meager. The parents of school-aged children paid for the community's schools and its instructors. During Indiana's pioneer era, Lincoln's limited formal schooling was not unusual.[81] Lincoln was taught by itinerant teachers at blab schools, which were schools for younger students, and paid by the students' parents.[82] Because school resources were scarce, much of a child's education was informal and took place outside the confines of a classroom.[83]

Family, neighbors, and schoolmates of Lincoln's youth recalled that he was an avid reader. Lincoln read Aesop's Fables, the Bible, The Pilgrim's Progress, Robinson Crusoe, and Parson Weems's The Life of Washington, as well as newspapers, hymnals, songbooks, and math and spelling books, among others.[84][85] Later studies included Shakespeare's works, poetry, and British and American history. Although Lincoln was unusually tall (6 feet 3.75 inches (1.9241 m)) and strong, he spent so much time reading that some neighbors thought he was lazy for all his "reading, scribbling, writing, ciphering, writing Poetry, etc."[86] and must have done it to avoid strenuous manual labor. His stepmother also acknowledged he did not enjoy "physical labor", but loved to read.[39] "He (Lincoln) read so much—was so studious—too[k] so little physical exercise—was so laborious in his studies," that years later, when Lincoln lived in Illinois, Henry McHenry remembered, "that he became emaciated and his best friends were afraid that he would craze himself."[87]

In addition to reading, Lincoln cultivated other skills and interests during his youth in Kentucky and Indiana. He developed a plain, backwoods style of speaking, which he practiced during his youth by telling stories and sermons to his family, schoolmates, and members of the local community. By the time he was twenty-one, Lincoln had become "an able and eloquent orator";[88] however, some historians have argued his speaking style, figures of speech, and vocabulary remained unrefined, even as he entered national politics.[89]

Move to Illinois (1830)

In 1830, when Lincoln was twenty-one years of age, thirteen members of the extended Lincoln family moved to Illinois. Thomas, Sally, Abraham, and Sally's son, John D. Johnston, went as one family. Dennis Hanks and his wife Elizabeth, who was also Abraham's stepsister, and their four children joined the party. Hanks's half-brother, Squire Hall, along with his wife, Matilda Johnston, another of Lincoln's stepsisters, and their son formed the third family group. Historians disagree on who initiated the move, but it may have been Dennis Hanks rather than Thomas Lincoln.[90] Thomas had no obvious reason to leave Indiana. He owned land and was a respected member of his community, but Hanks had not fared as well. In addition, John Hanks, one of Dennis's cousins, lived in Macon County, Illinois. Dennis later remarked that Sally refused to part with her daughter, Elizabeth, so Sally may have persuaded Thomas to move to Illinois.[91][92]

The Lincoln-Hanks-Hall families departed Indiana in early March 1830. It is generally agreed they crossed the Wabash River at Vincennes, Indiana, into Illinois, and the family settled on a site selected in Macon County, Illinois,[93] 10 miles (16 km) west of Decatur. Lincoln, who was twenty-one years old at the time, helped his father build a log cabin and fences, clear 10 acres (40,000 m2) of land, and put in a crop of corn. That autumn the entire family fell ill with a fever, but all survived. The early winter of 1831 was especially brutal, with many locals calling it the worst they had ever experienced. (In Illinois it was known as the "Winter of Deep Snow".) In the spring, as the Lincoln family prepared to move to a homestead in Coles County, Illinois, Abraham was ready to strike out on his own.[94] Thomas and Sally moved to Coles County, and remained in Illinois for the rest of their lives.[95]

Although Sally Lincoln and his cousin, Dennis Hanks, maintained that Thomas loved and supported his son, the father-son relationship became strained after the family moved to Illinois.[96] Perhaps Thomas did not fully appreciate his son's ambition, while Abraham never knew of Thomas's early struggles.[66] In 1851, after the move to Illinois, Abraham refused to visit his dying father, and failed to take his own sons to visit their grandparents. Historian Rodney O. Davis has argued that the reason for the strain in their relationship was due to Lincoln's success as a lawyer and his marriage to Mary Todd Lincoln, who came from a wealthy, aristocratic family, and the two men no longer related to each other's circumstances in life.[96]

Another trip to New Orleans (1831)

Lincoln, along with John Johnson and John Hanks, accepted an offer from Denton Offutt to meet in Springfield, Illinois, and take a load of cargo to New Orleans in 1831. Departing from Springfield in late April or early May along the Sangamon River, their boat had difficulty getting past a mill dam 20 miles (32 km) northwest of Springfield, near the village of New Salem. Offutt, who was impressed by New Salem's location and believed that steamboats could navigate the river to the village, made arrangements to rent the mill and open a general store. Offutt hired Lincoln as his clerk and the two men returned to New Salem after they discharged their cargo in New Orleans.[97]

New Salem (1831–1837)

Lincoln settles in

When Lincoln returned to New Salem in late July 1831, he found a promising community, but it probably never had a population that exceed a hundred residents. New Salem was a small commercial settlement that served several local communities. The village had a sawmill, grist mill, blacksmith shop, cooper's shop, wool carding shop, a hat maker, general store, and a tavern spread out over more than a dozen buildings. Offutt did not open his store until September, so Lincoln found temporary work in the interim and was quickly accepted by the townspeople as a hardworking and cooperative young man.[98] Once Lincoln began working in the store, he met a rougher crowd of settlers and workers from the surrounding communities, who came into New Salem to purchase supplies or have their corn ground. Lincoln's humor, storytelling abilities, and physical strength fit the young, raucous element that included the so-called Clary's Grove boys, and his place among them was cemented after a wrestling match with a local champion, Jack Armstrong. Although Lincoln lost the fight with Armstrong, he earned the respect of the locals.[99]

During his first winter in New Salem, Lincoln attended a meeting of the New Salem debating club. His performance in the club, along with his efficiency in managing the store, sawmill, and gristmill, in addition to his other efforts at self-improvement soon gained the attention of the town's leaders, such as Dr. John Allen, Mentor Graham, and James Rutledge.[100] The men encouraged Lincoln to enter politics, feeling that he was capable of supporting the interests of their community. In March 1832 Lincoln announced his candidacy in a written article that appeared in the Sangamo Journal, which was published in Springfield. While Lincoln admired Henry Clay and his American System, the national political climate was undergoing a change and local Illinois issues were the primary political concerns of the election. Lincoln opposed the development of a local railroad project, but supported improvements in the Sangamon River that would increase its navigability. Although the two-party political system that pitted Democrats against Whigs had not yet formed, Lincoln would become one of the leading Whigs in the state legislature within the next few years.[101]

By the spring of 1832, Offutt's business had failed and Lincoln was out of work. Around this time, the Black Hawk War erupted and Lincoln joined a group of volunteers from New Salem to repel Black Hawk, who was leading a group of 450 warriors along with 1,500 women and children to reclaim traditional tribal lands in Illinois. Lincoln was elected as captain of his unit, but he and his men never saw combat. Lincoln later commented In the late 1850s that the selection by his peers was "a success which gave me more pleasure than any I have had since." Lincoln returned to central Illinois after a few months of militia service to campaign in Sangamon County before the August 6 legislative election. When the votes were tallied, Lincoln finished eighth out of thirteen candidates. Only the top four candidates were elected, but Lincoln managed to secure 277 out of the 300 votes cast in the New Salem precinct.[102]

Without a job, Lincoln and William F. Berry, a member of Lincoln's militia company during the Black Hawk War, purchased one of the three general stores in New Salem. The two men signed personal notes to purchase the business and a later acquisition of another store's inventory, but their enterprise failed. By 1833 New Salem was no longer a growing community; the Sangamon River proved to be inadequate for commercial transportation and no roads or railroads allowed easy access to other markets. In January, Berry applied for a liquor license, but the added revenue was not enough to save the business.[103] With the closure of the Lincoln-Berry store, Lincoln was again unemployed and would soon have to leave New Salem. However, in May 1833, with the assistance of friends interested in keeping him in New Salem, Lincoln secured an appointment from President Andrew Jackson as the postmaster of New Salem, a position he kept for three years. During this time, Lincoln earned between $150 and $175 as postmaster, hardly enough to be considered a full-time source of income. Another friend helped Lincoln obtain an appointed as an assistant to county surveyor John Calhoun, a Democratic political appointee. Lincoln had no experience at surveying, but he relied on borrowed copies of two works and was able to teach himself the practical application of surveying techniques as well as the trigonometric basis of the process. His income proved sufficient to meet his day-to-day expenses, but the notes from his partnership with Berry were coming due.[104]

Politics and the law

In 1834 Lincoln's decision to run for the state legislature for a second time was strongly influenced by his need to satisfy his debts, what he jokingly referred to as his "national debt", and the additional income that would come from a legislative salary. By this time Lincoln was a member of the Whig party. His campaign strategy excluded a discussion of the national issues and concentrated on traveling throughout the district and greeting voters. The district's leading Whig candidate was Springfield attorney John Todd Stuart, whom Lincoln knew from his militia service during the Black Hawk War. Local Democrats, who feared Stuart more than Lincoln, offered to withdraw two of their candidates from the field of thirteen, where only the top four vote-getters would be elected, to support Lincoln. Stuart, who was confident of his own victory, told Lincoln to go ahead and accept the Democrats' endorsement. On August 4 Lincoln polled 1,376 votes, the second highest number of votes in the race, and won one of the four seats in the election, as did Stuart.[105] Lincoln was reelected to the state legislature in 1836, 1838, 1840, and 1844.

Stuart, a cousin of Lincoln's future wife, Mary Todd, was impressed with Lincoln and encouraged him to study law.[106] Lincoln was probably familiar with courtrooms from an early age. While the family was still in Kentucky, his father was frequently involved with filing land deeds, serving on juries, and attending sheriff's sales, and later, Lincoln may have been aware of his father's legal issues. When the family moved to Indiana, Lincoln lived within 15 miles (24 km) of three county courthouses. Attracted by the opportunity of hearing a good oral presentation, Lincoln, as did many others on the frontier, attended court sessions as a spectator. The practice continued when he moved to New Salem.[107] Noticing how often lawyers referred to them, Lincoln made a point of reading and studying the Revised Statutes of Indiana, the Declaration of Independence, and the United States Constitution.[108]

Using books borrowed from the law firm of Stuart and Judge Thomas Drummond, Lincoln began to study law in earnest during the first half of 1835.[109] Lincoln did not attend law school, and stated: "I studied with nobody."[87] As part of his training, he read copies of Blackstone's Commentaries, Chitty's Pleadings, Greenleaf's Evidence, and Joseph Story's Equity Jurisprudence.[110] In February 1836 Lincoln stopped working as a surveyor,[111] and in March 1836, took the first step to becoming a practicing attorney when he applied to the clerk of the Sangamon County Court to register as a man of good and moral character. After passing an oral examination by a panel of practicing attorneys, Lincoln received his law license on September 9, 1836. In April 1837 he was enrolled to practice before the Supreme Court of Illinois, and moved to Springfield where he went into partnership with Stuart.[112]

Illinois Legislature (1834–1842)

Lincoln's first session in the Illinois legislature ran from December 1, 1834, to February 13, 1835. In preparation for the session Lincoln borrowed $200 from Coleman Smoot, one of the richest men in Sangamon County, and spent $60 of it on his first suit of clothes. As the second youngest legislator in this term, and one of thirty-six first-time attendees, Lincoln was primarily an observer, but his colleagues soon recognized his mastery of "the technical language of the law" and asked him to draft bills for them.[113]

When Lincoln announced his bid for reelection in June 1836, he addressed the controversial issue of expanded suffrage. Democrats advocated universal suffrage for white males residing in the state for at least six months. They hoped to bring Irish immigrants, who were attracted to the state because of its canal projects, onto the voting rolls as Democrats. Lincoln supported the traditional Whig position that voting should be limited to property owners.[114]

Lincoln was reelected on August 1, 1836, as the top vote getter in the Sangamon delegation. This delegation of two senators and seven representatives was nicknamed the "Long Nine" because all of them were above average height. Despite being the second youngest of the group, Lincoln was viewed as the group's leader and the floor leader of the Whig minority. The Long Nine's primary agenda was the relocation of the state capital from Vandalia to Springfield and a vigorous program of internal improvements for the state.[115] Lincoln's influence within the legislature and within his party continued to grow with his reelection for two subsequent terms in 1838 and 1840. By the 1838–1839 legislative session, Lincoln served on at least fourteen committees and worked behind the scenes to manage the program of the Whig minority.[116]

While serving as a state legislator, Illinois Auditor James Shields challenged Lincoln to a duel. Lincoln had published an inflammatory letter in the Sangamon Journal, a Springfield newspaper, that poked fun at Shields. Lincoln's future wife, Mary Todd, and her close friend, continued writing letters about Shields without Lincoln's knowledge. Shields took offense to the articles and demanded "satisfaction". The incident escalated to the two parties meeting on Missouri's Sunflower Island, near Alton, Illinois, to participate in a duel, which was illegal in Illinois. Lincoln took responsibility for the articles and accepted. Lincoln choose cavalry broadswords as the duel's weapons because Shields was known as an excellent marksman. Just prior to engaging in combat, Lincoln demonstrated his physical advantage (his long arm reach) by easily cutting a branch above Shields's head. Their seconds intervened and convinced the men to cease hostilities on the grounds that Lincoln had not written the letters.[117][118][119][120]

Internal improvements

The Illinois governor called for a special legislative session during the winter of 1835–1836 in order to finance what became known as the Illinois and Michigan Canal, which connected the Illinois and Chicago rivers and linked Lake Michigan to the Mississippi River. The proposal would allow the state government to finance the construction with a $500,000 loan. Lincoln voted in favor of the commitment, which passed 28–27.[121]

Lincoln had always supported Henry Clay's vision of the American System, which saw a prosperous America supported by a well-developed network of roads, canals, and, later, railroads. Lincoln favored raising the funds for these projects through the federal government's sale of public lands to eliminate interest expenses; otherwise, private capital should bear the cost alone. Fearing that Illinois would fall behind other states in economic development, Lincoln shifted his position to allow the state to provide the necessary support for private developers.[114]

In the next session a newly elected legislator, Stephen A. Douglas, went even further and proposed a comprehensive $10 million state loan program, which Lincoln supported. However, the Panic of 1837 effectively destroyed the possibility of more internal improvements in Illinois. The state became "littered with unfinished roads and partially dug canals"; the value of state bonds fell; and interest on the state's debts was eight times its total revenue. The state government took forty years to pay off this debt.[122]

Lincoln had a couple of ideas to salvage the internal improvements program. First, he proposed that the state buy public lands at a discount from the federal government and then sell them to new settlers at a profit, but the federal government rejected the idea. Next, he proposed a graduated land tax that would have passed more of the tax burden to the owners of the most valuable land, but the majority of the legislators were unwilling to commit any further state funds to internal improvement projects. The state's financial depression continued through 1839.[123]

Selection of Springfield as the state capital

In the 1830s Illinois welcomed more immigrants, many from New York and New England, who tended to move into the northern and central parts of the state. Vandalia, which was located in the more stagnant southern section, seemed less unsuitable as the state's seat of government. On the other hand, Springfield, in Sangamon County, was "strategically located in central Illinois" and was already growing "in population and refinement".[124]

Those who opposed the relocation of the state government to Springfield first attempted to weaken the Sangamon County delegation's influence by dividing the county into two new counties, but Lincoln was instrumental in first amending and then killing this proposal in his own committee. Throughout the lengthy debate "Lincoln's political skills were repeatedly tested". He finally succeeded when the legislature accepted his proposal that the chosen city would be required to contribute $50,000 and 2 acres (8,100 m2) of land for construction of a new state capitol building—only Springfield could comfortably meet this financial demand. The final action was tabled twice, but Lincoln resurrected it by finding acceptable amendments to draw additional support, including one that would have allowed reconsideration in the next session. As other locations were voted down, Springfield was selected by a 46 to 37 vote margin on February 28, 1837. Under Lincoln's leadership reconsideration efforts were defeated in the 1838–1839 sessions.[125] Orville Browning, who would later become a close Lincoln friend and confidant, guided the legislation through the Illinois Senate, and the move became effective in 1839.[126]

Illinois State Bank

Lincoln, like Henry Clay, favored federal control over the nation's banking system, but President Jackson had effectively killed the Bank of the United States by 1835. That same year Lincoln crossed party lines to vote with pro-bank Democrats in chartering the Illinois State Bank. As he did in the internal improvements debates, Lincoln searched for the best available alternative.[127] According to historian and Lincoln biographer Richard Carwardine, Lincoln felt:

A well-regulated bank would provide a sound, elastic currency, protecting the public against the extreme prescriptions of the hard-money men on one side and the paper inflationists on the other; it would be a safe depository for public funds and provide the credit mechanisms needed to sustain state improvements; it would bring an end to extortionate money-lending.[123]

Opponents of the state bank initiated an investigation designed to close the bank in the 1836–1837 legislative session. On January 11, 1837, Lincoln made his first major legislative speech supporting the bank and attacking its opponents. He condemned "that lawless and mobocratic spirit ... which is already abroad in the land, and is spreading with rapid and fearful impetuosity, to the ultimate overthrow of every institution, or even moral principle, in which persons and property have hitherto found security."[128] Blaming the opposition entirely on the political class, Lincoln called politicians "at least one long step removed from honest men,"[129] Lincoln commented:

I make the assertion boldly, and without fear of contradiction, that no man, who does not hold an office, or does not aspire to one, has ever found any fault of the Bank. It has doubled the prices of the products of their farms, and filled their pockets with a sound circulating medium, and they are all well pleased with its operations.[130]

Westerners in the Jacksonian Era were generally skeptical of all banks, and this was aggravated after the Panic of 1837, when the Illinois Bank suspended specie payments. Lincoln still defended the bank, but it was too strongly linked to a failing credit system that lead to devalued currency and loan foreclosures to generate much political support.[131]

In 1839 Democrats led another investigation of the state bank, with Lincoln as a Whig representative on the investigating committee. Lincoln was instrumental in the committee's conclusion that the suspension of specie payment was related to uncontrollable economic conditions rather than "any organic defects of the institutions themselves."[132] However, the legislation allowing the suspension of specie payments was set to expire at the end of December 1840, and Democrats wanted to adjourn without further extensions. In an attempt to avoid a quorum on adjournment, Lincoln and several others jumped out of a first story window, but the Speaker counted them as present and "the bank was killed."[132][133] By 1841 Lincoln was less supportive of the state bank, although he would continue to make speeches around the state supporting it. He concluded, "If there was to be this continual warfare against the Institutions of the State ... the sooner it was brought to an end the better."[134]

Abolitionism

In the 1830s the slaveholding states began to take notice of the growth of antislavery rhetoric in the North. Their anger focused on abolitionists, whom they accused of fomenting slave revolts by distributing "incendiary pamphlets" of the slaves. When southern legislatures passed resolutions calling for suppression of abolitionist societies, they often received a favorable response from their northern counterparts. In January 1837 the Illinois legislature passed a resolution declaring that they "highly disapprove of the formation of abolition societies", that "the right of property in slaves is sacred to the slave-holding States by the Federal Government, and that they cannot be deprived of that right without their consent", and that "the General Government cannot abolish slavery in the District of Columbia, against the will of the citizens of said District." The vote in the Illinois Senate was 18 to 0, and 77 to 6 in the House, with Lincoln and Dan Stone, who was also from Sangamon County, voting in opposition. Because relocation of the state capital was still the number one issue on the two men's agendas, they made no comment on their votes until the relocation was approved.[135]

On March 3, with his other legislative priorities behind him, Lincoln filed a formal written protest with the legislature that stated "the institution of slavery is founded on both injustice and bad policy."[136] Lincoln criticized abolitionists on practical grounds, arguing that "the promulgation of abolition doctrines tends rather to increase than to abate its [slavery's] evils."[137] He also addressed the issue of slavery in the nation's capital in a different manner from the resolutions, writing that "the Congress of the United States has the power, under the constitution, to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia; but that power ought not to be exercised unless at the request of the people of said District."[138] Lincoln biographer Benjamin P. Thomas commented on the significance of Lincoln's action:

Thus, at the age of twenty-eight, Lincoln made public avowal of his dislike of slavery, basing his position on moral grounds when he characterized the institution as an injustice with evils, while conceding the sanctity of Southern rights. In 1860, in his autobiography, he stated that the protest "briefly defined his position on the slavery question; and so far as it goes, it was then the same that it is now.[139]

Lincoln's Lyceum Address

Lincoln's address to the Young Men's Lyceum of Springfield, Illinois on January 27, 1838, was titled "The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions".[140][141] In this speech Lincoln described the dangers of slavery in the United States, an institution he believed would corrupt the federal government.[140]

Prairie Lawyer

Partnerships with Stuart and Logan

In 1837, from the start of the law partnership with Stuart, Lincoln handled most of the firms clients, while Stuart was primarily concerned with politics and election to the United States House of Representatives. The law practice had as many clients as it could handle. Most fees were five dollars, with the common fee ranging between two and a half dollars and ten dollars. Lincoln quickly realized that he was equal in ability and effectiveness to most other attorneys, whether they were self-taught like Lincoln or had studied with a more experienced lawyer. Following Stuart's elected to Congress in November 1839, Lincoln ran the practice on his own. Lincoln, like Stuart, considered his legal career as simply a catalyst to his political ambitions.[142]

By 1840 Lincoln was drawing $1,000 annually from the law practice, along with his salary as a legislator. However, when Stuart was reelected to Congress, Lincoln was no longer content to carry the entire load. In April 1841 he entered into a new partnership with Stephen T. Logan. Logan was nine years older than Lincoln, the leading attorney in Sangamon County, and a former attorney in Kentucky before he moved to Illinois. Logan saw Lincoln as a complement to his practice, recognizing that Lincoln's effectiveness with juries was superior to his own in that area. Once again, clients were plentiful for the firm, although Lincoln received one-third of the firm's proceeds rather than the even split he had enjoyed with Stuart.[143]

Lincoln's association with Logan was a learning experience. He absorbed from Logan some of the finer points of law and the importance of proper and detailed case research and preparation. Logan's written pleadings were precise and on point, and Lincoln used them as his model. However, much of Lincoln's development was still self-taught. Historian David Herbert Donald wrote that Logan taught him that "there was more to law than common sense and simple equity" and Lincoln's study began to focus on "procedures and precedents."[144] During this time Lincoln did not study law books, but he did spend "night after night in the Supreme Court Library, searching out precedents that applied to the cases he was working on."[144] Lincoln stated, "I love to dig up the question by the roots and hold it up and dry it before the fires of the mind."[144] His written briefs, especially important in Illinois Supreme Court cases, were prepared in great detail with precedents noted that often went back to the origins of English common law. Lincoln's growing skills became evident as his appearances before the Supreme Court increased and would serve him well in his political career. By the time he went to Washington in 1861 Lincoln had appeared over three hundred times before this court.[145] Lincoln biographer Stephen B. Oates wrote, "It was here that he earned his reputation as a lawyer's lawyer, adept at meticulous preparation and cogent argument."[146]

Lincoln and Herndon

Lincoln's partnership with Logan was dissolved in the fall of 1844, when Logan entered into a partnership with his son. Lincoln, who probably could have had his choice of more established attorneys, was tired of being the junior partner and entered into partnership with William Herndon, who had been reading law in the offices of Logan and Lincoln. Herndon, like Lincoln, was an active Whig, but the party in Illinois at that time was split into two factions. Lincoln was connected to the older, "silk stocking" element of the party through his marriage to Mary Todd; Herndon was one of the leaders of the younger, more populist portion of the party. The Lincoln-Herndon partnership continued through Lincoln's presidential election, and Lincoln remained a partner of record until his death.[147]

Prior to his partnership with Herndon, Lincoln had not regularly attended court in neighboring communities. This changed as Lincoln became one of the most active regulars on the circuit through 1854, interrupted only by his two-year stint in Congress. The Eighth Circuit covered 11,000 square miles (28,000 km2). Each spring and fall Lincoln traveled the district for nine to ten weeks at a time, netting around $150 for each ten-week circuit. On the road, lawyers and judges lived in cheap hotels, with two lawyers to a bed; six or eight men to a room.[148]

Lincoln's reputation for integrity and fairness on the circuit led to him being in high demand both from clients and local attorneys who needed assistance. It was during his time riding the circuit that he picked up one of his lasting nicknames, "Honest Abe". The clients he represented, the men he rode the circuit with, and the lawyers he met along the way became some of Lincoln's most loyal political supporters.[149] One of these was David Davis, a fellow Whig who, like Lincoln, promoted nationalist economic programs and opposed slavery without actually becoming an abolitionist. Davis joined the circuit in 1848 as a judge and would occasionally appoint Lincoln to fill in for him. They traveled the circuit for eleven years, and Lincoln would eventually appoint him to the United States Supreme Court.[150] Another close associate was Ward Hill Lamon, an attorney in Danville, Illinois. Lamon, the only local attorney with whom Lincoln had a formal working agreement, accompanied Lincoln to Washington in 1861.[151]

Case load and income

Unlike other attorneys on the circuit, Lincoln did not supplement his income by engaging in real estate speculation or operating a business or a farm. His income was generally what he earned practicing law. In the 1840s this amounted to $1,500 to $2,500 a year, increasing to $3,000 in the early 1850s, and was $5,000 by the mid-1850s.[152]

Criminal law made up the smallest portion of Lincoln and Herndon's case work. In 1850 the firm was involved in eighteen percent of the cases on the Sangamon County Circuit; by 1853 it had grown to thirty-three percent. On his return from his single term in the U.S. House of Representatives, Lincoln turned down an offer of a partnership in a Chicago law firm.[153] Based strictly on the volume of cases, Lincoln was "undoubtedly one of the outstanding lawyers of central Illinois." Lincoln was also in demand on the federal courts. He received important retainers from cases in the United States Northern District Court in Chicago.[154]

Lincoln was involved in at least two cases involving slavery. In an 1841 Illinois Supreme Court case, Bailey v. Cromwell, Lincoln successfully prevented the sale of a woman who was alleged to be a slave, making the argument that in Illinois "the presumption of law was ... that every person was free, without regard to color." In 1847 Abraham Lincoln defended Robert Matson, a slave owner who was trying to retrieve his runaway slaves. Matson brought slaves from his Kentucky plantation to work on land he owned in Illinois.[155] The slaves were represented by Orlando Ficklin, Usher Linder, and Charles H. Constable.[156] The slaves ran away because they believed that once they were in Illinois they were free, since the Northwest Ordinance forbade slavery in the territory that included Illinois. In this case, Lincoln invoked the right of transit, which allowed slaveholders to take their slaves temporarily into free territory. Lincoln also stressed that Matson did not intend to have the slaves remain permanently in Illinois. Even with these arguments, judges in Coles County ruled against Lincoln and the slaves were set free.[157] Donald notes, "Neither the Matson case nor the Cromwell case should be taken as an indication of Lincoln's views on slavery; his business was law, not morality."[158] The right of transit was a legal theory recognized by some of the free states that a slaveowner could take slaves into a free state and retain ownership as long as the intent was not to permanently settle in the free state.

Railroads became an important economic force in Illinois in the 1850s. As they expanded they created myriad legal issues regarding "charters and franchises; problems relating to right-of-way; problems concerning evaluation and taxation; problems relating to the duties of common carriers and the rights of passengers; problems concerning merger, consolidation, and receivership." Lincoln and other attorneys would soon find that railroad litigation was a major source of income. Like the slave cases, sometimes Lincoln would represent the railroads and sometimes he would represent their adversaries. He had no legal or political agenda that was reflected in his choice of clients. Herndon referred to Lincoln as "purely and entirely a case lawyer."[159]

In one notable 1851 case, Lincoln represented the Alton and Sangamon Railroad in a dispute with James A. Barret, a shareholder. Barret refused to pay the balance on his pledge to the railroad on the grounds that it had changed its originally planned route. Lincoln argued that as a matter of law a corporation is not bound by its original charter when that charter can be amended in the public interest. Lincoln also argued that the newer route proposed by Alton and Sangamon was superior and less expensive, and accordingly, the corporation had a right to sue Barret for his delinquent payment. Lincoln won this case and the Illinois Supreme Court decision was eventually cited by other U.S. courts.[160]

The most important civil case for Lincoln was the landmark Hurd v. Rock Island Bridge Company, also known as the Effie Afton case. America's expansion west, which Lincoln strongly supported, was seen as an economic threat to the river trade, which ran north-to-south, primarily along the Mississippi River. In 1856 a steamboat collided with a bridge built by the Rock Island Railroad between Rock Island, Illinois, and Davenport, Iowa. It was the first railroad bridge to span the Mississippi River. The steamboat owner sued for damages, claiming the bridge was a hazard to navigation, but Lincoln argued in court for the railroad and won, removing a costly impediment to western expansion by establishing the right of land routes to bridge waterways.[161]

Possibly the most notable criminal trial of Lincoln's career as a lawyer came in 1858, when he defended the son of Lincoln's friend, Jack Armstrong. William "Duff" Armstrong had been charged with murder. The case became famous for Lincoln's use of judicial notice—a rare tactic at that time—to show that an eyewitness had lied on the stand. After the witness testified to having seen the crime by moonlight, Lincoln produced a Farmers' Almanac to show that the moon on that date was at such a low angle it could not have provided enough illumination to see anything clearly. Based almost entirely on this evidence, Armstrong was acquitted.[162]

Lincoln was involved in more than 5,100 cases in Illinois alone during his 23-year legal career. Though many of these cases involved little more than filing a writ, others were more substantial and quite involved. Lincoln and his partners appeared before the Illinois State Supreme Court more than 400 times.

Lincoln the inventor

Abraham Lincoln is the only U.S. president to have been awarded a patent for an invention. As a young man, Lincoln took a boatload of merchandise down the Mississippi River from New Salem to New Orleans. At one point the boat slid onto a dam and was set free only after heroic efforts. In later years, while traveling on the Great Lakes, Lincoln's ship ran afoul of a sandbar. The resulting invention consists of a set of bellows attached to the hull of a ship just below the water line. On reaching a shallow place, the bellows are filled with air and the vessel, thus buoyed, is expected to float clear. The invention was never marketed, probably because the extra weight would have increased the probability of running onto sandbars more frequently. Lincoln whittled the model for his patent application with his own hands. It is on display at the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of American History.[163] Patent #6469 for "A Device for Buoying Vessels Over Shoals" was issued May 22, 1849.[164]

In 1858 Lincoln called the introduction of patent laws one of the three most important developments "in the world's history." His words, "The patent system added the fuel of interest to the fire of genius," are inscribed over the US Commerce Department's north entrance.[165]

Courtships, marriage, and family

Soon after he moved to New Salem, Lincoln met Ann Rutledge. Historians do not agree on the significance or nature of their relationship, but according to many she was his first and perhaps most passionate love. At first they were probably just close friends, but soon they had reached an understanding that they would be married as soon as Ann had completed her studies at the Female Academy in Jacksonville. Their plans were cut short in the summer of 1835, when what was probably typhoid fever hit New Salem. Ann died on August 25, 1835, and Lincoln went through a period of extreme melancholy that lasted for months.[166][167]

In either 1833 or 1834, Lincoln had met Mary Owens, the sister of his friend Elizabeth Abell, when she was visiting from her home in Kentucky. In 1836, in a conversation with Elizabeth, Lincoln agreed to court Mary if she ever returned to New Salem.[168] Mary returned in November 1836, and Lincoln courted her for a time, but they had second thoughts about their relationship. On August 16, 1837, Lincoln wrote Mary a letter from Springfield suggesting an end to the relationship. She never replied and the courtship was over.[169]

In 1839 Mary Todd moved from her family's home in Lexington, Kentucky, to Springfield and the home of her eldest sister, Elizabeth Porter (née Todd) Edwards, and Elizabeth's husband, Ninian W. Edwards, son of Ninian Edwards. Mary was popular in the Springfield social scene, but soon was attracted to Lincoln. Sometime in 1840 the two became engaged. They initially set a January 1, 1841, wedding date, but mutually called it off.[171] During the break in their courtship, Lincoln briefly courted Sarah Rickard, whom he had known since 1837. Lincoln proposed marriage to Sarah in 1841 but was rejected. Sarah later said that "his peculiar manner and his General deportment would not be likely to fascinate a young girl just entering the society world".[172]

Lincoln still had conflicted feelings concerning Mary Todd. In August 1841 he visited Joshua Speed, his close friend and former roommate, who had moved to Louisville, Kentucky. Lincoln met Speed's fiancee while there, and after his return to Springfield. Speed and Lincoln corresponded over Speed's own doubts about marriage. Lincoln advised Speed and helped convince him to proceed with the marriage. In turn, Speed urged Lincoln to do the same. Lincoln resumed his courtship of Mary, and on November 4, 1842, they were married at the Edwards's home. In a letter written a few days after the wedding, Lincoln wrote, "Nothing new here except my marrying, which to me, is matter of profound wonder."[173]

The couple had four sons. Robert Todd Lincoln was born in Springfield, Illinois, on August 1, 1843. He was their only child to survive into adulthood. Young Robert attended Phillips Exeter Academy and Harvard College. Robert died on July 26, 1926, in Manchester, Vermont. The other Lincoln sons were born in Springfield, Illinois, and died either during childhood or their teen years. Edward Baker Lincoln was born on March 10, 1846, and died on February 1, 1850, in Springfield. William Wallace Lincoln was born on December 21, 1850, and died on February 20, 1862, in Washington, D.C., during President Lincoln's first term. Thomas "Tad" Lincoln was born on April 4, 1853, and died on July 16, 1871, in Chicago, Illinois.

During the American Civil War, four of Mary Todd Lincoln's brothers fought for the Confederacy, with one wounded and another killed in action. Lieutenant David H. Todd, Mary's half-brother, served as commandant of the Libby Prison camp during the war.

State and National politics

Campaigning for Congress (1843)

In the winter of 1842–1843, with the strong encouragement of his wife, Lincoln decided to pursue election to the United States House of Representatives from the newly created Seventh Congressional District. His main rivals were his friends, Edward D. Baker and John J. Hardin. On February 14 Lincoln told a local Whig political leader, "if you should hear any one say that Lincoln don't want to go to Congress, I wish you as a personal friend of mine, would tell him you have reason to believe he is mistaken. The truth is, I would like to go very much."[174]

At the end of February the Whigs met in Springfield, where Lincoln wrote the party platform "opposing direct federal taxes and endorsing a protective tariff, a national bank, distribution to the states of proceeeds from federal land sales, and the convention system of choosing candidates."[175] Baker and Lincoln campaigned vigorously throughout March, but Lincoln, believing that Baker had an insurmountable lead, withdrew when the Sangamon County convention was held on March 20. Lincoln was selected as a delegate to the district convention which met on May 1 in Pekin. Although Lincoln worked hard for Baker, Hardin was selected as the Whig candidate, winning by a single vote. Lincoln then initiated a resolution that endorsed Baker for the nomination in two years. The resolution passed, which seemed to set a precedent for a single term with rotation among the party's leaders, and suggested that Lincoln would be next in line after Baker.[176]

Campaigning for Henry Clay (1844)

In 1844 Lincoln campaigned enthusiastically for Henry Clay, the Whig nominee for president and a personal hero of Lincoln. On the campaign trail Lincoln and the other Illinois Whigs emphasized tariff issues, while touting the economic success of the Tariff of 1842 that had been passed in Congress under Whig leadership. Part of the campaign pitted Lincoln in a series of debates against Democrat John Calhoun, a candidate for Congress. Campaigning in Illinois for most of 1844, Lincoln spoke out against the annexation of Texas (a potential slave territory), promoted national and state banks, and opposed a wave of nativism that would become a major political issue a decade later. On the last issue Lincoln declared that "the guarantee of the rights of conscience, as found in our Constitution, is most sacred and inviolable, and one that belongs no less to the Catholic, than to the Protestant; and that all attempts to abridge or interfere with these rights, either of Catholic or Protestant, directly or indirectly, have our decided disapprobation, and shall ever have our most effective opposition."[177]

Clay's opponent, James K. Polk, carried Illinois and also won the presidency. In Illinois and elsewhere Polk's support for the acquisition of Texas and Oregon seemed to carry the day. Lincoln and many other Whigs blamed the free soil Liberty Party for dividing the vote in New York, which allowed Polk to carry that state and achieve the majority in the electoral college. In responding to an antislavery Whig, who equated voting for Clay, a slaveholder, as "do[ing] evil", Lincoln asked, "If the fruit of electing Mr. Clay would have been to prevent the extension of slavery, could the act of electing him have been evil?"[178]

Campaigning for Congress (1846)

Hardin did not run for reelection in 1844; the Whig nomination, as previously agreed, went to Baker, who won election to the seat. Baker agreed not to run for reelection in 1846, but Hardin considered a run for his old seat. Much of the Seventh District was included within the judicial circuit that Lincoln rode, so beginning in September 1845, he began soliciting the support of Whig leaders and editors as he moved through the circuit. Lincoln emphasized that Hardin should be bound by the understanding reached at Pekin in 1843. The debate over what had actually been agreed on in 1843 became public and bitter. In the end Hardin withdrew and Lincoln secured the Whig nomination. The Democrats nominated Peter Cartwright, a circuit-riding Methodist preacher.[179]

Lincoln campaigned throughout the district, where he was already well known. Although he was presented with campaign funds $200, Lincoln returned most of the money after the election. Speaking of his actual campaign expenses, Lincoln noted, "I made the canvass on my own horse; my entertainment, being at the houses of friends, cost me nothing; and my only outlay was seventy-five cents for a barrel of cider which some farm-hands insisted I should treat them to." There were few newspaper accounts of the election, but the major political issues were the annexation of Texas, which Lincoln opposed as an expansion of slavery; the Mexican War, on which Lincoln was noncommittal; and the Oregon border dispute with Great Britain, which Lincoln avoided.[180]

Cartwright avoided joint appearances with Lincoln and initiated a "whispering campaign" that accused Lincoln of being an infidel and a religious skeptic. Lincoln responded by pointing out that the Illinois constitution had no religious qualifications for office. On July 31 he published a handbill that admitted he was not a member of a specific Christian church, but denied that he was an "open scoffer at Christianity" or had ever "denied the truth of the Scriptures." Cartwright's campaign was effective only in counties where Lincoln was not personally known. Lincoln won the election with 56 percent of the vote, topping the numbers of Hardin (53 percent) and Baker (52 percent) in their elections. Due to the timing of the elections, the Thirtieth Congress did not convene until December 1847.[181]

House of Representatives (1847–1849)

A Whig and an admirer of party leader Henry Clay, Lincoln was elected to a term in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1846. As a freshman House member, he was not a particularly powerful or influential figure. He spoke out against the Mexican–American War, which he attributed to President Polk's desire for "military glory—that attractive rainbow, that rises in showers of blood." He also challenged the President's claims regarding the Texas boundary and offered Spot Resolutions demanding to know the "spot" on U.S. soil where blood was first spilt.[182] In January 1848 Lincoln was among the eighty-two Whigs who defeated eighty-one Democrats in a procedural vote on an amendment to send a routine resolution back to committee with instructions to add the words "a war unnecessarily and unconstitutionally begun by the President of the United States." The amendment passed, but the bill never reemerged from committee and was never finally voted upon.[183]

Lincoln later damaged his political reputation with a speech in which he declared, "God of Heaven has forgotten to defend the weak and innocent, and permitted the strong band of murderers and demons from hell to kill men, women, and children, and lay waste and pillage the land of the just." Two weeks later, President Polk sent a peace treaty to Congress. While no one in Washington paid attention to Lincoln, the Democrats orchestrated angry outbursts from across his district, where the war was popular and many had volunteered. In Morgan County, Illinois, resolutions were adopted in fervent support of the war and in wrathful denunciation of the "treasonable assaults of guerrillas at home; party demagogues; slanderers of the President; defenders of the butchery at the Alamo; traducers of the heroism at San Jacinto".[184] Warned by his law partner, William Herndon, that the damage was mounting and irreparable, Lincoln decided not to run for reelection.

Campaigning for Zachary Taylor (1848)

In the 1848 presidential election, Lincoln supported war hero Zachary Taylor for the Whig nomination and for president in the general election. In abandoning Clay, Lincoln argued that Taylor was the only Whig that was electable. Lincoln attended the Whig National Convention in Philadelphia as a Taylor delegate. Following Taylor's successful nomination, Lincoln urged Taylor to run a campaign emphasizing his personal traits, while leaving the controversial issues to be resolved by Congress. While Congress was in session Lincoln spoke in favor of Taylor on the House floor, and when it adjourned in August, he remained in Washington to assist Whig Executive Committee of Congress in the campaign. In September Lincoln made campaign speeches in Boston and other New England locations. Remembering the election of 1844, Lincoln addressed potential Free Soil voters by saying that the Whigs were equally opposed to slavery and the only issue was how they could most effectively vote against the expansion of slavery. Lincoln argued that a vote for the Free Soil candidate, former President Martin Van Buren, would divide the antislavery vote and give the election to the Democratic candidate, Lewis Cass.[185]

With Taylor's victory, the incoming administration, perhaps remembering Lincoln's criticism of Taylor during the Mexican–American War, offered Lincoln only the governorship of remote Oregon Territory. Acceptance would end his career in the fast-growing state of Illinois, so he declined., and returned to Springfield, Illinois, where he turned most of his energies to his law practice.[186]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Louis A. Warren (1991). Lincoln's Youth: Indiana Years, Seven to Twenty-One, 1816–1830. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. pp. 3–4. ISBN 0-87195-063-4.

- ↑ Warren, p. 4.

- ↑ Michael Burlingame (2008). Abraham Lincoln: A Life. I. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-0-80188-993-6.

- ↑ Warren, p. 5.

- 1 2 William E. Bartelt (2008). There I Grew Up: Remembering Abraham Lincoln's Indiana Youth. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-87195-263-9.

- ↑ Burlingame, v. I, p. 2–3.

- ↑ Warren, p. 6.

- ↑ Warren, p. 6 and 8.

- ↑ Warren, p. 9.

- ↑ William E. Barton (1920). The Paternity of Abraham Lincoln: Was He the Son of Thomas Lincoln? An Essay on the Chastity of Nancy Hanks. George H. Doran Company. pp. 19, 203 and 319.

- ↑ Doug Wead (2005). The Raising of a President: The Mothers and Fathers of Our Nation's Leaders. Simon & Schuster. p. 101. ISBN 0-7434-9726-0.

- ↑ "Abraham Lincoln, A North Carolinian". Bostic Lincoln Center. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

- ↑ David J. Jacobson (1948). The Affairs of Dame Rumor. New York: Rinehart and Co. p. 191.

- 1 2 Carl Sandburg (1926). Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years. 2. New York: Harcourt Brace. p. 381.

- 1 2 Warren, p. 210.

- ↑ Warren, p. 134–35.

- ↑ Bartelt, p. 67–68.

- ↑ William Lee Miller (2002). Lincoln's Virtues: An Ethical Biography (Vintage Books ed.). New York: Random House/Vintage Books. p. 4. ISBN 0-375-40158-X.

- 1 2 3 Emanuel Hertz (1938). The Hidden Lincoln: From the Letters and Papers of William H. Herndon. New York: Viking Press. pp. 413–14.

- ↑ "Lincoln, Abraham, personal description of (To Josephus Hewett), Feb. 13, 1848", in Archer H. Shaw, compiler and ed. (1950). The Lincoln Encyclopedia: The Spoken and Written Words of A. Lincoln Arranged For Ready Reference. New York: Macmillan. p. 190. References "nearly ten years ago"—meaning 1838–39.

- ↑ "To F. W. Fell, Dec. 20, 1859", in Shaw, The Lincoln Encyclopedia, p. 288.

- ↑ Coley Taylor and Samuel Middlebrook (1936). The Eagle Screams. New York: Macaulay. p. 106 and 109.

- ↑ David Herbert Donald (1995). Lincoln. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 1 and 116–18.

- ↑ Bartelt, p. 1 and 9. Both of the Lincoln biographical sketches appeared in the newspapers, while Lincoln's response to Scripps also appeared as part of the reporter's biography of Lincoln, which was published in July 1860.

- ↑ Miller, p. 17.

- ↑ Bartelt, p. 60 and 61.

- ↑ David Herbert Donald (1948). Lincoln's Herndon. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 181.

- ↑ Warren, p. 9–10.

- ↑ Bartelt, p. 14.

- 1 2 3 4 Warren, p. 12.

- ↑ Warren, p. 10.

- ↑ Donald, Lincoln, p. 22 and 24.

- ↑ Warren, p. 13.

- ↑ Donald, Lincoln, p. 23–24.

- ↑ Bartelt, p. 12 and 14.

- ↑ Bartelt, p. 109.

- ↑ Bartelt, p. 12.

- ↑ Bartelt, p. 41 and 135.

- 1 2 3 Bartelt, p. 66.

- ↑ Bartelt, p. 68, 73–74, and 136.

- ↑ Warren, p. xvii and xx.

- ↑ Warren, p. 26.

- ↑ Warren, p. 16 and 43.

- ↑ Bartelt, p. 3, 5, and 16.

- ↑ Warren, p. 16 and 19.

- ↑ Bartelt, p. 11.

- 1 2 Bartelt, p. 24.

- ↑ Warren, p. 41.

- ↑ Bartelt, p. 69.

- ↑ Bartelt, p. 34.

- ↑ Warren, p. 42.

- ↑ Bartelt, p. 25 and 71.

- ↑ James H. Madison (2014). Hoosiers: A New History of Indiana. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press and Indiana Historical Society Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-253-01308-8.

- ↑ Bartelt, p. 34 and 156.

- ↑ Bartelt, p. 24 and 104.

- ↑ Warren, p. xxi and 16.

- ↑ Bartelt, p. 18 and 20.

- ↑ Bartelt, p. 22–23, and 77.

- ↑ Dennis Hanks was the ward and nephew of Nancy's aunt, Elizabeth Sparrow and her husband Thomas. He arrived in Indiana with the Sparrows in 1817 and lived with the Sparrows on the Lincoln farm. Hanks moved into the Lincoln home after both the Sparrows died of milk sickness the week before Nancy's death. In 1821 Dennis married Lincoln's stepsister, Elizabeth Johnston. See Bartelt, p. 77 and 97, and Warren, p. 51, 53, and 58.

- ↑ Bartelt, p. 23 and 83.