Bradley County, Arkansas

| Bradley County, Arkansas | |

|---|---|

Bradley County Courthouse | |

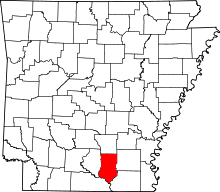

Location in the U.S. state of Arkansas | |

Arkansas's location in the U.S. | |

| Founded | December 18, 1840 |

| Named for | Hugh Bradley |

| Seat | Warren |

| Largest city | Warren |

| Area | |

| • Total | 653 sq mi (1,691 km2) |

| • Land | 649 sq mi (1,681 km2) |

| • Water | 3.7 sq mi (10 km2), 0.6% |

| Population (est.) | |

| • (2015) | 11,094 |

| • Density | 18/sq mi (7/km²) |

| Congressional district | 4th |

| Time zone | Central: UTC-6/-5 |

| Website |

www |

Bradley County is a county located in the U.S. state of Arkansas. As of the 2010 census, the population was 11,508.[1] The county seat is Warren.[2] It is Arkansas's 43rd county, formed on December 18, 1840, and named for Captain Hugh Bradley, who fought in the War of 1812. It is an alcohol prohibition or dry county, and is the home of the world-famous Bradley County Pink Tomato Festival.

History

Indigenous peoples of various cultures had lived along the rivers of Arkansas for thousands of years and created complex societies. Mississippian culture peoples built massive earthwork mounds along the Ouachita River beginning about 1000 CE.

Caddo Tribe

The Felsenthal refuge at the south end of Bradley County contains over 200 native American achaeological sites, primarily from the Caddo tribe that lived in the area as long as 5,000 years ago. These sites include the remains of seasonal fishing camps, ceremonial plazas, temple mounds and large villages containing as many as 200 structures.

French and Spanish control

After Hernando de Soto's exploration of the Mississippi Valley during the 1540s, there is little evidence of any European activity in the Ouachita River valley until the latter 17th century.

Mississippi Company

Louis XIV's long reign and wars had nearly bankrupted the French monarchy. Rather than reduce spending, the Regency of Louis XV of France endorsed the monetary theories of John Law a Scottish financier. In 1716, Law was given a charter for the Banque Royale under which the national debt was assigned to the bank in return for extraordinary privileges. The key to the Banque Royale agreement was that the national debt would be paid from revenues derived from opening the Mississippi Valley. The Bank was tied to other ventures of Law—the Company of the West and the Companies of the Indies. All were known as the Mississippi Company. The Mississippi Company had a monopoly on trade and mineral wealth. The Company boomed on paper. Law was given the title Duc d'Arkansas. Bernard de la Harpe and his party left New Orleans in 1719 to explore the Red River. In 1721, he explored the Arkansas River. At the Yazoo settlements in Mississippi he was joined by Jean Benjamin who became the scientist for the expedition.

In 1718, there were only 700 people in Louisiana. The Mississippi Company arranged ships to move hundred (800) people landed in Louisiana on one day in 1718, doubling the population.

John Law encouraged Germans, particularly Germans of the Alsatian region who had recently fallen under French rule, and the Swiss to emigrate.

Alsace was transformed into a mosaic of Catholic and Protestant territories. Alsace was sold to France within the greater context of the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648). Beset by enemies and to gain a free hand in Hungary, the Habsburgs sold their Sundgau territory (mostly in Upper Alsace) to France in 1646, which had occupied it, for the sum of 1.2 million Thalers.

Prisoners were set free in Paris in September 1719 and later, under the condition that they marry prostitutes and go with them to Louisiana. The newly married couples were chained together and taken to the port of embarkation. After complaints from the Mississippi Company and the concessioners about this class of French immigrants, in May, 1720, the French government prohibited such deportations. But, there was third shipment in 1721.

The Jesuit Charlevoix went from Canada to Louisiana. His letter said "these 9,000 Germans, who were raised in the Palatinate (Alsace part of France) were in Arkansas. The Germans left Arkansas en masse. They went to New Orleans and demanded passage to Europe. The Mississippi Company gave the Germans rich lands on the right bank of the Mississippi River about 25 miles above New Orleans. The area is now known as 'the German Coast'."[3]

Estonia

Sweden lost Swedish Livonia, Swedish Estonia and Ingria to Russia almost 100 years later, by the Capitulation of Estonia and Livonia in 1710 and the Treaty of Nystad in 1721. Charles Fred. D'Arensbourg emigrated to Louisiana in 1721 with thirty officers. They would rather move to Louisiana, instead living as Russians.

French

European interest in the region then came in three distinct waves. The French hunters, trappers, and traders appeared first and operated along the Ouachita River valley until the Natchez revolt of 1729, which frightened away any developers for a while. Next, in the 1740s and 1750s, French settlers meandered north from the Pointe Coupee Post in south French Louisiana and named many of bayous. These settlers returned south to Pointe Coupee before the Spaniards took possession of Louisiana in the late 1760s. The third wave of European settlers were actually descendants of the second wave, mostly true Louisiana Creoles born near the Point Coupee and Opelousas Posts. Additionally, a few Canadians came down the river from the Arkansas Post, and a few native French traders also operated along the river in the 1770s.

Prior to 1782, with the exception of occasional failed colonization schemes, the Europeans ignored the vast Ouachita Valley, which extended from the area around Hot Springs, Arkansas southward towards the Mississippi River in Louisiana. This changed with the 1779–1782 war between England and Spain. After their defeat at the Battle of Baton Rouge in 1779, the English yielded control of Natchez to the Spaniards, and this led to several years of fighting as the English settlers resisted Spanish rule over them. After the ultimate English defeat, many settlers fled to the Ouachita Valley region, creating the threat of English/American rebel activity in the Ouachita Valley region. This prompted the Spanish governor, Don Bernardo, the Comte de Galvez, to establish a strong buffer zone between the independent American states and the Spanish province of Louisiana. In 1781 Galvez created the “Poste d'Ouachita” and named Jean-Baptist Filhiol (also known as Don Juan Filhiol) as the commandant. Filhiol served in this capacity between 1782 and 1804, and through his service helped to keep a firm Spanish grip on activities in the region.

Filhiol, his new wife, and a few others arrived in the Ouachita country in April 1782. He traveled up the river, past present-day Union Parish, to the old trading post called “Ecore a Fabri” (now Camden). For various reasons, after a few years Filhiol decided not to build his headquarters there and took his group back down river to the "Prairie des Canots".

Many Louisiana Creole people arrived in Louisiana following the Slave Uprising led by Toussaint Breda (later called L'Overture) in 1791 in Ste. Dominique, later called Haiti.

In 1801, Spanish Governor Don Juan Manuel de Salcedo took over for Governor Marquess of Casa Calvo, and the right to deposit goods from the United States was fully restored. Napoleon Bonaparte returned Louisiana to French control from Spain in 1800, under the Treaty of San Ildefonso (Louisiana had been a Spanish colony since 1762.) However, the treaty was kept secret, and Louisiana remained under Spanish control until a transfer of power to France on November 30, 1803, just three weeks before the cession to the United States.

James Monroe and Robert R. Livingston traveled to Paris to negotiate the purchase in 1802. Their interest was only in the port and its environs; they did not anticipate the much larger transfer of territory that would follow.

The Louisiana Purchase was the acquisition by the United States of America of 828,800 square miles (2,147,000 km2) of France's claim to the territory of Louisiana in 1803.

Name origins

- L'Aigles Creek, Aigle "Eagle Creek", Eagle Lake.

- Bogalusa. A place on the Saline River near the Ouachita River (a different place with the same name is Bogalusa, Louisiana).

- Charivari Creek, south of Hilo (a French folk custom in which the community gave a noisy, discordant mock serenade, also pounding on pots and pans, at the home of newlyweds. )

- Felsenthal a Germanic word meaning "hills and valleys" or "rocky valleys."

- Moreau Bayou de Moreau (or Moro Creek, Moro Bay) Moreau is a French surname.

- Pereogeethe Lake. Pereo (Latin: Disappearance, death, loss.) Geethe (Estonian: female name)

Early American period

During the period 1837–1861, settlers arrived from Mississippi, Alabama, Tennessee, and Georgia. Prior to 1860, to reach the available farmland of northwestern Louisiana and southwestern Arkansas, settlers from the Gulf Coast states most often crossed the Mississippi River at Natchez, then came up the Ouachita River.

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 653 square miles (1,690 km2), of which 649 square miles (1,680 km2) is land and 3.7 square miles (9.6 km2) (0.6%) is water.[4]

The Mississippi Embayment extends to the Saline River valley along the east and southeast edge of Bradley County. The Ouachita River runs along the southwest edge of the county. The Saline River (Ouachita River) flows along most of the east edge of the County. The L'Aigle Creek (Saline River of the Ouachita River) drains most of the area in the County.

Major highways

Adjacent counties

- Cleveland County (north)

- Drew County (east)

- Ashley County (southeast)

- Union County (southwest)

- Calhoun County (west)

National protected area

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 3,829 | — | |

| 1860 | 8,388 | 119.1% | |

| 1870 | 8,646 | 3.1% | |

| 1880 | 6,285 | −27.3% | |

| 1890 | 7,972 | 26.8% | |

| 1900 | 9,651 | 21.1% | |

| 1910 | 14,518 | 50.4% | |

| 1920 | 15,970 | 10.0% | |

| 1930 | 17,494 | 9.5% | |

| 1940 | 18,097 | 3.4% | |

| 1950 | 15,987 | −11.7% | |

| 1960 | 14,029 | −12.2% | |

| 1970 | 12,778 | −8.9% | |

| 1980 | 13,803 | 8.0% | |

| 1990 | 11,793 | −14.6% | |

| 2000 | 12,600 | 6.8% | |

| 2010 | 11,508 | −8.7% | |

| Est. 2015 | 11,094 | [5] | −3.6% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[6] 1790–1960[7] 1900–1990[8] 1990–2000[9] 2010–2015[1] | |||

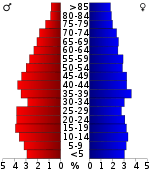

As of the 2010 United States Census, there were 11,508 people residing in the county. 60.3% were White, 27.6% Black or African American, 0.5% Native American, 0.2% Asian, 10.1% of some other race and 1.3% of two or more races. 13.2% were Hispanic or Latino (of any race).

At the 2006 United States Census estimate,[11] there were 18,873 people, 13,103 households and 9,346 families residing in the county. The population density was 19 per square mile (7/km²). There were 7,002 housing units at an average density of 9 per square mile (4/km²). The racial makeup of the county was 53.36% White, 39.63% Black or African American, 0.24% Native American, 0.06% Asian, 0.01% Pacific Islander, 4.91% from other races, and 0.75% from two or more races. 4.25% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 6,421 households of which 29.50% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 52.20% were married couples living together, 14.50% had a female householder with no husband present, and 29.90% were non-families. 27.60% of all households were made up of individuals and 13.90% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.45 and the average family size was 2.96.

23.60% of the population were under the age of 18, 9.70% from 18 to 24, 26.50% from 25 to 44, 22.80% from 45 to 64, and 17.50% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38 years. For every 100 females there were 97.70 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 95.80 males.

The median household income was $38,936, and the median family income was $47,094. Males had a median income of $32,779 versus $27,167 for females. The per capita income for the county was $42,346. About 20.60% of families and 26.30% of the population were below the poverty line, including 33.10% of those under age 18 and 20.80% of those age 65 or over.

Government

| Year | GOP | DNC | Others |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 59.2% 2,164 | 36.1% 1,317 | 4.7% 172 |

| 2012 | 58.3% 2,118 | 39.8% 1,447 | 1.9% 69 |

| 2008 | 56.0% 2,262 | 41.6% 1,680 | 2.4% 99 |

| 2004 | 47.3% 2,011 | 51.9% 2,206 | 0.8% 32 |

| 2000 | 45.1% 1,793 | 53.3% 2,122 | 1.6% 64 |

Communities

Cities

Town

Unincorporated communities

Townships

Townships in Arkansas are the divisions of a county. Each township includes unincorporated areas; some may have incorporated cities or towns within part of their boundaries. Arkansas townships have limited purposes in modern times. However, the United States Census does list Arkansas population based on townships (sometimes referred to as "county subdivisions" or "minor civil divisions"). Townships are also of value for historical purposes in terms of genealogical research. Each town or city is within one or more townships in an Arkansas county based on census maps and publications. The townships of Bradley County are listed below; listed in parentheses are the cities, towns, and/or census-designated places that are fully or partially inside the township. [13][14]

- Clay (Banks)

- Eagle

- Marion

- Moro

- Ouachita

- Palestine

- Pennington (Warren)

- River

- Sumpter

- Washington (Hermitage)

See also

- List of lakes in Bradley County, Arkansas

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Bradley County, Arkansas

References

- 1 2 "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 19, 2014.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on 2011-05-31. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=aTP8fxliBI4C&pg=PA11&lpg=PA11&dq=%22mississippi+company%22+%22john+law%22+ships+prostitutes&source=bl&ots=t_r34u7o2A&sig=tuEtbwiJIlZXa0--pwTxT6LRSM8&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0CDEQ6AEwA2oVChMIlv_wmc-YyAIVT3uSCh0AfQdi#v=onepage&q=%22mississippi%20company%22%20%22john%20law%22%20ships%20prostitutes&f=false Cat Island: The History of a Mississippi Gulf Coast Barrier Island, By John Cuevas

- ↑ "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- ↑ "County Totals Dataset: Population, Population Change and Estimated Components of Population Change: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- ↑ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- ↑ Forstall, Richard L., ed. (March 27, 1995). "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- ↑ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. April 2, 2001. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- ↑ Based on 2000 census data

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2013-09-11. Retrieved 2011-05-14.

- ↑ "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ↑ 2011 Boundary and Annexation Survey (BAS): Bradley County, AR (PDF) (Map). U. S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 2011-08-24.

- ↑ "Arkansas: 2010 Census Block Maps - County Subdivision". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 27, 2014.

External links

- Bradley County Pink Tomato Festival

- Bradley County Chamber of Commerce

- Bradley County Industrial Development Corporation

- Felsenthal Historical Topographic Map 1:62,500 1938

- Ingalls Historical Topographic Map 1:62,500 1936 (1.9MB)

- Ingalls Topographic Map 1986

- Moro Bay Historical Topographic Map 1:62,500 1937 (3.0MB)

- Bayou Bartholomew, Saline River, Henri Joutel

- Pre-European Exploration, Prehistory through 1540

- European Exploration and Settlement, 1541 through 1802

- Arkansas Territory 1819, a Journal of Travels

- Arkansas Territory map 1832 by Henry Schenck Tanner

|

Cleveland County |  | ||

| Calhoun County | |

Drew County | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Union County | Ashley County |

Coordinates: 33°29′39″N 92°08′42″W / 33.49417°N 92.14500°W