List of National Treasures of Japan (writings: Japanese books)

The term "National Treasure" has been used in Japan to denote cultural properties since 1897,[1][2] although the definition and the criteria have changed since the introduction of the term. The written materials in the list adhere to the current definition, and have been designated National Treasures according to the Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties that came into effect on June 9, 1951. The items are selected by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology based on their "especially high historical or artistic value".[3][4]

Writing was introduced from Korea to Japan around 400 AD (in the form of Chinese books), with work done in Chinese by immigrant scribes from the mainland.[nb 1][5][6][7] Literacy remained at an extremely marginal level in the 5th and 6th centuries, but during the 7th century a small number of Japanese scholar-aristocrats such as Prince Shōtoku began to write in Chinese for official purposes and in order to promote Buddhism.[8][9] By the late 7th century, reading and writing had become an integral part of life of some sections of the ruling and intellectual classes, particularly in government and religion.[10] The earliest extant large-scale works compiled in Japan are the historical chronicles Kojiki (712) and Nihon Shoki (720).[9] Other early Japanese works from the Nara period include biographies of Prince Shōtoku, cultural and geographical records (fudoki) and the Man'yōshū, the first anthology of Japanese poetry. Necessarily all of these works were either written in Chinese or in a hybrid Japanese-Chinese style and were modeled on Chinese prototypes. The development of a distinct Japanese script (kana) in the 9th century was the starting point of the classical age of Japanese literature and led to a number of new, uniquely Japanese genres of literature, such as tales (monogatari) or diaries (nikki). Because of the strong interest and support in literature of the Heian court, writing activities flourished particularly in the 10th and 11th centuries.

This list contains books of various type that have been compiled in Classical and early Feudal Japan. More than half of the 68 designated treasures are works of poetry and prose. Another large segment consists of historical works such as manuscripts of Kojiki and Nihon Shoki; the rest are books of various type such as dictionaries, law books, biographies or music scores. The designated manuscripts date from 9th century Heian period to the Edo period with most dating to the Heian period. They are housed in temples, museums, libraries or archives, universities and in private collections.[4]

The objects in this list represent about one third of the 223 National Treasures in the category "writings". They are complemented by 56 Chinese book National Treasures and 99 other written National Treasures.[4]

Statistics

.png)

| Prefecture | City | National Treasures |

|---|---|---|

| Aichi | Nagoya | 1 |

| Fukuoka | Dazaifu | 1 |

| Kagawa | Takamatsu | 1 |

| Kōchi | Kōchi | 1 |

| Kyoto | Kyoto | 27 |

| Miyagi | Sendai | 1 |

| Nara | Nara | 2 |

| Tenri | 3 | |

| Osaka | Izumi | 1 |

| Kawachinagano | 2 | |

| Minoh | 1 | |

| Osaka | 2 | |

| Saga | Saga | 1 |

| Shiga | Ōtsu | 1 |

| Tokyo | Tokyo | 22 |

| Yamaguchi | Hōfu | 1 |

| Period[nb 2] | National Treasures |

|---|---|

| Heian period | 50 |

| Kamakura period | 16 |

| Nanboku-chō period | 2 |

Usage

The table's columns (except for Remarks and Image) are sortable by pressing the arrows symbols. The following gives an overview of what is included in the table and how the sorting works.

- Name: the name as registered in the Database of National Cultural Properties[4]

- Authors: name of the author(s)

- Remarks: information about the type of document and its content

- Date: period and year; the column entries sort by year. If only a period is known, they sort by the start year of that period.

- Format: principal type, technique and dimensions; the column entries sort by the main type: scroll (includes handscrolls and letters), books (includes albums, ordinary bound books and books bound by fukuro-toji)[nb 3] and other (includes hanging scrolls)

- Present location: "temple/museum/shrine-name town-name prefecture-name"; the column entries sort as "prefecture-name town-name".

- Image: picture of the manuscript or of a characteristic document in a group of manuscripts

Treasures

Japanese literature

The adaption of the Chinese script, introduced in Japan in the 5th or 6th century, followed by the 9th century development of a script more suitable to write in the Japanese language, is reflected in ancient and classical Japanese literature from the 7th to 13th century. This process also caused unique genres of Japanese literature to evolve from earlier works modelled on Chinese prototypes.[11][12] The earliest traces of Japanese literature date to the 7th century and consist of Japanese verse (waka) and poetry written in Chinese by Japanese poets (kanshi).[13][14][15] While the latter showed little literary merit compared to the large volume of poems composed in China, waka poetry made great progress in the Nara period culminating in the Man'yōshū, an anthology of more than 4,000 pieces of mainly tanka ("short poem") from the period up to the mid-8th century.[16][17][18] Until the 9th century, Japanese language texts were written in Chinese characters via the man'yōgana writing system, generally using the phonetic value of the characters. Since longer passages written in this system became unmanageably long, man'yōgana was used mainly for poetry while classical Chinese was reserved for prose.[19][20][21] Consequently, the prose passages in the Man'yōshū are in Chinese and the Kojiki (712), the oldest extant chronicle, uses man'yōgana only for the songs and poems.[19][20]

A revolutionary achievement was the development of kana, a true Japanese script, in the mid to late 9th century.[22] This new script enabled Japanese authors to write more easily in their own language and led to a variety of vernacular prose literature in the 10th century such as tales (monogatari) and poetic journals (nikki).[22][23][24] Japanese waka poetry and Japanese prose reached their highest developments around the 10th century, supported by the general revival of traditional values and the high status ascribed to literature by the Heian court.[21][25][26] The Heian period (794 to 1185) is therefore generally referred to as the classical age of Japanese literature.[27] Being the language of scholarship, government and religion, Chinese was still practiced by the male nobility of the 10th century while for the most part aristocratic women wrote diaries, memoirs, poetry and fiction in the new script.[28] The Tale of Genji written in the early 11th century by a noblewoman (Murasaki Shikibu) is according to Helen Craig McCullough the "single most impressive accomplishment of Heian civilization".[29]

Another literary genre called setsuwa ("informative narration") goes back to orally transmitted myths, legends, folktales, and anecdotes. Setsuwa comprise the oldest Japanese tales, were originally Buddhist influenced, and were meant to be educational.[30][31] The oldest setsuwa collection is the Nihon Ryōiki (early 9th century). With a widening religious and social interest of the aristocracy, setsuwa collections were compiled again in the late 11th century starting with the Konjaku Monogatarishū[32][33] The high quality of the Tale of Genji influenced the literature into the 11th and 12th centuries.[24][33] A large number of monogatari and some of the best poetic treatises were written in the early Kamakura period (around 1200).[34]

Waka

Waka (lit. "Japanese poem") or uta (song) is an important genre of Japanese literature. The term originated in the Heian period to distinguish Japanese-language poetry from kanshi, poetry written in Chinese by Japanese authors.[35][36] Waka began as an oral tradition, in tales, festivals and rituals,[nb 4] and began to be written in the 7th century.[14][37][38] In the Asuka and Nara periods, "waka" included a number of poetic forms such as tanka ("short poems"), chōka ("long poems"), bussokusekika, sedōka ("memorized poem") and katauta ("poem fragment"), but by the 10th century only the 31-syllable tanka survived.[35][39][40] The Man'yōshū, of the mid-8th century, is the primary record of early Japanese poetry and the first waka anthology.[16][41] It contains the three main forms of poetry at time of compilation: 4,200 tanka, 260 chōka and 60 sedōka; dating from 759 backwards more than one century.[nb 5][20][42]

The early 9th century, however, was a period of direct imitation of Chinese models making kanshi the major form of poetry at the time.[43][44] In the late 9th century, waka and the development of kana script rose simultaneously with the general revival of traditional values, culminating in the compilation of the first imperial waka anthology, the Kokinshū, in 905.[26][45] It was followed in 951 by the Gosen Wakashū; in all seven imperial anthologies were compiled in the Heian period.[46][47] The main poetic subjects were love and the four seasons; the standards of vocabulary, grammar and style, established in the Kokinshū, dominated waka composition into the 19th century.[45][48][49]

For aristocrats to succeed in private and public life during the Heian period, it was essential to be fluent in the composition and appreciation of waka, as well as having thorough knowledge of and ability in music, and calligraphy.[45][50][51] Poetry was used in witty conversations, in notes of invitation, thanks or condolence, and for correspondence between friends and lovers.[47][52][53] Some of the finest poetry of the Heian period came from the middle-class court society such as ladies in waiting or middle-rank officials.[47] Utaawase poetry contests, in which poets composed poetry on a given theme to be judged by an individual, were held from 885 onwards, and became a regular activity for Heian courtiers from the 10th century onward.[47][49][54] Contest judgments led to works about waka theory and critical studies. Poems from the contents were added to imperial anthologies.[47][55] Critical theories, and the poems in the anthologies (particularly the Kokinshū), became the basis for judgments in the contests.[56] Utaawase continued to be held through the late-11th century, as social rather than literary events. Held in opulence in a spirit of friendly rivalry, they included chanters, scribes, consultants, musicians, and an audience.[55][57] During the Heian period, waka were often collected in large anthologies, such as the Man'yōshū or Kokinshū, or smaller private collections of the works of a single poet.[45] Waka also featured highly in all kinds of literary prose works including monogatari, diaries and historical works.[28][47] The Tale of Genji alone contains 800 waka.[50]

At the end of the Heian period, the aristocracy lost political and economical power to warrior clans, but retained the prestige as custodians of high culture and literature.[34][58] Nostalgia for the Heian court past, considered then as classical Japanese past (as opposed to Chinese past), created a renaissance in the arts and led to a blossoming of waka in the early Kamakura period.[34][59][60] Poets of middle and lower rank, such as Fujiwara no Shunzei, Saigyō Hōshi and Fujiwara no Teika, analyzed earlier works, wrote critical commentaries, and added new aesthetic values such as yūgen to waka poetry.[61][62][63] Some of the best imperial anthologies and best poetic anthologies, such as Shunzei's Korai fūteishō, were created in the early Kamakura period.[34] The audience was extended from the aristocracy to high ranking warriors and priests, who began to compose waka. [64][65][66] By the 14th century, linked verse or renga superseded waka poetry in importance.[67][68]

There are 29 National Treasures of 14 collections of waka and two works on waka style, compiled from between the 8th and the mid-13th century with most from the Heian period. The two works of waka theory are Wakatai jisshu (945) and Korai fūteishō (1197). The collections include the two first imperial waka anthologies: Kokinshū (905, ten treasures) and Gosen Wakashū (951); seven private anthologies: Man'yōshū (after 759, three treasures), Shinsō Hishō (1008), Nyūdō Udaijin-shū (before 1065), Sanjūrokunin Kashū (ca. 1112), Ruijū Koshū (before 1120), Shūi Gusō (1216), Myōe Shōnin Kashū (1248); and five utaawase contents: including one imaginary content (Kasen utaawase), the Konoe edition of the Poetry Match in Ten Scrolls (three treasures), Ruijū utaawase, the Poetry competition in 29 rounds at Hirota Shrine and the Record of Poetry Match in Fifteen Rounds. The designated manuscripts of these works found in this list date from the Heian and Kamakura periods.[4]

| Name | Authors | Remarks | Date | Format | Present location | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves (万葉集 Man'yōshū)[69][70] | possibly Fujiwara no Korefusa (藤原伊房), grandson of Fujiwara no Yukinari | Also called Aigami Edition (or Ranshi Edition) after the blue dyed paper; transcription is said to have been completed within 4 days only (according to postscript in first volume); written in a masculine style atypical for the period | late Heian period | Fragments of one handscroll (vol. 9), ink on aigami dyed paper, 26.6 cm × 1,133 cm (10.5 in × 446.1 in) | Kyoto National Museum, Kyoto |  |

| Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves (万葉集 Man'yōshū) or Kanazawa Manyō (金沢万葉) | unknown | Handed down in the Maeda clan which had its headquarters in Kanazawa | Heian period, 11th century | One bound book (fragments of vol. 3 (two sheets) and 6 (five sheets)), ink on decorative paper with five-colored design (彩牋 saisen), 21.8 cm × 13.6 cm (8.6 in × 5.4 in) | Maeda Ikutokukai, Tokyo |  |

| Anthology of Ten Thousand Leaves, Genryaku Edition (元暦校本万葉集 Genryaku kōbon Man'yōshū)[71] | various | Man'yōshū edition with the largest number of poems | Heian period, 11th century; vol. 6: Kamakura period, 12th century; postscript on vol. 20 from June 9, 1184 | 20 books bound by fukuro-toji,[nb 3] ink on decorated paper, 25.0 cm × 17.0 cm (9.8 in × 6.7 in) | Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo | |

| Collected Japanese Poems of Ancient and Modern Times (古今集 Kokinshū) | attributed to Fujiwara no Kiyosuke (藤原清輔) | — |

Heian period, 12th century | Two bound books | Maeda Ikutokukai, Tokyo |  |

| Collected Japanese Poems of Ancient and Modern Times (古今集 Kokinshū), Kōya edition | unknown | Oldest extant manuscript of the Kokin Wakashū | Heian period | Fragments of scroll 19 | Maeda Ikutokukai, Tokyo | .jpg) |

| Collected Japanese Poems of Ancient and Modern Times (古今和歌集 Kokin Wakashū), Gen'ei edition[72][73] | possibly Fujiwara no Sadazane, grandson of Fujiwara no Yukinari | Oldest complete manuscript of the Kokin Wakashū | Heian period, July 24, 1120 | Two bound books, ink on decorative paper, 21.1 cm × 15.5 cm (8.3 in × 6.1 in) | Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo |  |

| Collected Japanese Poems of Ancient and Modern Times (古今和歌集 Kokin Wakashū), Manshu-in edition | unknown | — |

Heian period, 11th century | One scroll, ink on colored paper | Manshu-in, Kyoto |  |

| Collected Japanese Poems of Ancient and Modern Times (古今和歌集 Kokin Wakashū) | transcription by Fujiwara no Teika | With attached imperial letters by Emperor Go-Tsuchimikado, Emperor Go-Nara and the draft of a letter by Emperor Go-Kashiwabara | Kamakura period, April 9, 1226 | One bound book | Reizei-ke Shiguretei Bunko (冷泉家時雨亭文庫), Kyoto |  |

| Collected Japanese Poems of Ancient and Modern Times (古今和歌集 Kokin Wakashū), Kōya edition | unknown | Oldest extant manuscript of the Kokin Wakashū | Heian period, 11th century | One handscroll (no. 5), ink on decorative paper, 26.4 cm × 573.6 cm (10.4 in × 225.8 in) | private, Tokyo |  |

| Collected Japanese Poems of Ancient and Modern Times (古今和歌集 Kokin Wakashū), Honami edition[74][75] | unknown | The name of the edition refers to the painter Honami Kōetsu who once owned this scroll; 49 waka from the twelfth volume ("Poems of Love, II); written on imported, Chinese paper with design of mica-imprinted bamboo and peach blossoms | late Heian period, 11th century | Fragments of one scroll (no 12), ink on decorated paper. 16.7 cm × 317.0 cm (6.6 in × 124.8 in) | Kyoto National Museum, Kyoto |  |

| Collected Japanese Poems of Ancient and Modern Times (古今和歌集 Kokin Wakashū), Kōya edition | unknown | Oldest extant manuscript of the Kokin Wakashū | Heian period, 11th century | One scroll (no. 20) | Tosa Yamauchi Family Treasury and Archives, Kōchi, Kōchi | |

| Collected Japanese Poems of Ancient and Modern Times (古今和歌集 Kokin Wakashū), Kōya edition[76] | possibly Fujiwara no Yukinari | Oldest extant manuscript of the Kokin Wakashū | Heian period, 11th century | One scroll (no. 8), ink on decorated paper | Mōri Museum, Hōfu, Yamaguchi |  |

| Preface to the Collected Japanese Poems of Ancient and Modern Times (古今和歌集序 Kokin Wakashū-jō) | attributed to Minamoto no Shunrai | — |

Heian period, 12th century | One handscroll, 33 sheets, ink on colored paper | Okura Museum of Art, Tokyo |  |

| Later Collection (後撰和歌集 Gosen Wakashū) | collated by Fujiwara no Teika | 1,425 poems, primarily those that were rejected for inclusion in the Kokin Wakashū | Kamakura period, March 2, 1234 | One bound book | Reizei-ke Shiguretei Bunko (冷泉家時雨亭文庫), Kyoto |  |

| Poetry Contest (歌合 utaawase), ten volume edition | purportedly Prince Munetaka | Handed down in the Konoe clan | Heian period, 11th century | Five scrolls (vol. 1, 2, 3, 8, 10), ink on paper | Maeda Ikutokukai, Tokyo | |

| Poetry Contest (歌合 utaawase), ten volume edition | purportedly Prince Munetaka | Handed down in the Konoe clan | Heian period, 11th century | One scroll (vol. 6), ink on paper, 28.8 cm × 284.1 cm (11.3 in × 111.9 in) | Yōmei Bunko, Kyoto |  |

| Poetry Contest of Great Poets (歌仙歌合 kasen utaawase)[77] | attributed to Fujiwara no Yukinari | Poems in two-column style of 30 famous poets including Kakinomoto no Hitomaro and Ki no Tsurayuki | Heian period, mid 11th century | One scroll, ink on paper | Kobuso Memorial Museum of Arts, Izumi (和泉市久保惣記念美術館), Izumi, Osaka | |

| Poems from the Poetry Match Held by the Empress in the Kanpyō era (寛平御時后宮歌合 kanpyō no ontoki kisai no miya utaawase)[78] | purportedly Prince Munetaka | This scroll was part of the fourth scroll of the ten scroll Poetry Match in Ten Scrolls which was handed down in the Konoe clan; contains 36 of the extant 43 poems from this collection | Heian period, 11th century | One scroll, ink on paper, 28.8 cm × 1,133.2 cm (11.3 in × 446.1 in) | Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo |  |

| Foolish Verses of the Court Chamberlain (拾遺愚草 Shūi gusō, lit.: Gleanings of Stupid Grass)[79] | Fujiwara no Teika | Private anthology of 2,885 poems by Fujiwara no Teika | Kamakura period, 1216 | Three bound books | Reizei-ke Shiguretei Bunko (冷泉家時雨亭文庫), Kyoto |  |

| Notes on Poetic Style Through the Ages (古来風躰抄 korai fūteishō) | Fujiwara no Shunzei | Original (first) edition | Kamakura period, 1197 | Two bound books | Reizei-ke Shiguretei Bunko (冷泉家時雨亭文庫), Kyoto |  |

| Record of Poetry Match in Fifteen Rounds (十五番歌合 Jūgoban utaawase) | Fujiwara no Korefusa (藤原伊房), grandson of Fujiwara no Yukinari | — |

Heian period, 11th century | One scroll, colored paper, 25.3 cm × 532.0 cm (10.0 in × 209.4 in) | Maeda Ikutokukai, Tokyo |  |

| Poetry competition in 29 rounds at Hirota Shrine (広田社二十九番歌合 Hirota-sha nijūkuban utaawase) | Fujiwara no Shunzei | — |

Heian period, 1172 | Three scrolls, ink on paper | Maeda Ikutokukai, Tokyo |  |

| Ten Varieties of Waka Style (和歌躰十種 Wakatai jisshu)[80] | Possibly Fujiwara no Tadaie[nb 6] | Discussion of the ten waka styles with five examples written in hiragana each; also named "Ten Styles of Tadamine" after the purported author of the 945 original work, Mibu no Tadamine; oldest extant manuscript of this work | Heian period, circa 1000 | One scroll, ink on decorative paper, 26.0 cm × 324.0 cm (10.2 in × 127.6 in); one hanging scroll (fragment of a book), ink on decorative paper, 26.0 cm × 13.4 cm (10.2 in × 5.3 in) | Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo |  |

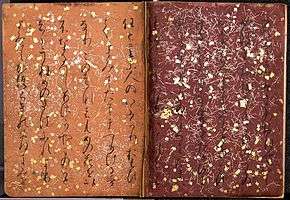

| Collection of 36 poets (三十六人家集 sanjūrokunin kashū), Nishi Hongan-ji edition[81] | unknown | Attached to the nomination is a letter by Emperor Go-Nara | Heian period, around 1100 (32 bound books); Kamakura period (one bound book), Edo period (four bound books) | 37 bound books | Nishi Honganji, Kyoto | |

| Poetry Match on Related Themes (類聚歌合 Ruijū utaawase), 20 volume edition | compiled by Minamoto Masazane and Fujiwara no Tadamichi | Large scale compilation of poetry contents until 1126; project started by Minamoto Masazane who was later joined by Fujiwara no Tadamichi | Heian period, 12th century | 19 scrolls, ink on paper, 26.8 cm × 2,406.4 cm (10.6 in × 947.4 in) (vol. 8) and 27.0 cm × 2,637.1 cm (10.6 in × 1,038.2 in) (vol. 11) | Yōmei Bunko, Kyoto |  |

| Ruijū Koshū (類聚古集, lit. Collection of similar ancient literature)[82][83] | Fujiwara no Atsutaka (藤原敦隆) | Re-edited version of the Man'yōshū; poems are categorized by themes such as: season, heaven and earth, and landscape; written in man'yōgana followed by hiragana. | Heian period, before 1120 | 16 bound books, ink on paper | Ryukoku University, Kyoto |  |

| Collection of Poems by Priest Myōe (明恵上人歌集 Myōe Shōnin Kashū)[84][85] | Kōshin (高信) | Collection of 112 poems by Myōe and 43 by other poets, compiled by Myōe's disciple Kōshin on the 17th anniversary of Myōe's death | Kamakura period, 1248 | One handscroll, ink on paper, 27.8 cm × 1,350 cm (10.9 in × 531.5 in) | Kyoto National Museum, Kyoto |  |

| Collection concealed behind a secluded window (深窓秘抄 Shinsō Hishō) | Fujiwara no Kintō | Collection of 101 poems | Heian period, 1008 | One scroll, ink on paper, 26.3 cm × 830 cm (10.4 in × 326.8 in) | Fujita Art Museum, Osaka |  |

| Nyūdō Udaijin-shū (入道右大臣集)[86] | Minamoto no Shunrai and Fujiwara no Teika (pages 6 and 7) | Transcription of poetry anthology by Fujiwara no Yorimune (藤原頼宗) | Heian period | One book bound of 31 pages by fukuro-toji,[nb 3] ink on decorative paper with five-colored design (彩牋 saisen) | Maeda Ikutokukai, Tokyo |  |

Monogatari, Japanese-Chinese poetry, setsuwa

There are ten National Treasures of six works of Japanese prose and mixed Chinese-Japanese poetry compiled from between the early 9th and the first half of the 13th century. The manuscripts in this list date from between the early 10th to the second half of the 13th century.[4] The three volume Nihon Ryōiki was compiled by the private[nb 7] priest Kyōkai around 822.[87][88][89] It is the oldest collection of Japanese anecdotes or folk stories (setsuwa) which probably came out of an oral tradition.[87][89] Combining Buddhism with local folk stories, this work demonstrates karmic causality and functioned as a handbook for preaching.[87][88][90] Two[nb 8] out of four[nb 9] extant distinct but incomplete manuscripts have been designated as a National Treasures.[91]

One of the earliest kana materials and one of the oldest extant works of Japanese prose fiction is the Tosa Diary written by Ki no Tsurayuki in 935.[92][93][94] It is also the oldest Japanese travel diary, giving an account of a return journey to Kyoto after a four-year term as prefect of Tosa Province.[95][96][97] The diary consists of close to 60 poems,[nb 10] connected by prose sections that detail the circumstances and the inspiration for the composition of the poems.[24][98][99] The work has been valued as a model for composition in the Japanese style.[100] The original manuscript by Ki no Tsurayuki had been stored at Rengeō-in palace library, and later was in the possession of Ashikaga Yoshimasa, after which its trace is lost.[6] All surviving manuscripts of the Tosa Diary are copies of this Rengeō-in manuscript.[101] The oldest extant of these, by Fujiwara no Teika, dates to 1235. One year later his son, Fujiwara no Tameie, produced another copy based on the original. Both transcriptions are complete facsimiles of the original, inclusive of the text, the layout, orthographical usages, and calligraphy.[nb 11][101] They have been designated as National Treasures.[4]

The 984 Sanbō Ekotoba ("The three jewels" or "Tale of the three brothers" or "Notes on the pictures of the three jewels"), was written by Minamoto no Tamenori in Chinese for the amusement of a young tonsured princess.[102][103][104] It is a collection of Buddhist tales and a guide to important Buddhist ceremonies and figures in Japanese Buddhist history.[105][106] The designated manuscript from 1273 is known as the Tōji Kanchiin[nb 12] manuscript and is the second oldest of the Sanbō Ekotoba. It is virtually complete unlike the late Heian period (Tōdaiji-gire) which is a scattered assortment of fragments.[107]

The cultural interaction between Japan and China is exemplified by the Wakan Rōeishū, a collection of 234 Chinese poems, 353 poems written in Chinese by Japanese poets (kanshi) and 216 waka, all arranged by topic.[108][109][110] Compiled in the early 11th century by Fujiwara no Kintō, it was the first and most successful work of this genre.[111][112][113] The English title, "Japanese-Chinese Recitation Collection" indicates that the poems in this collection were meant to be sung.[111][112][113] The Wakan Rōeishū has been valued as a source for poetry recitation, waka composition and for its calligraphy, as it displayed kana and kanji.[109][114] Three manuscripts of the Wakan Rōeishū written on decorated paper have been designated as National Treasures: the two scrolls at the Kyoto National Museum contain a complete transcription of the work and are a rare and fully developed example of calligraphy on an ashide-e[nb 13] ground;[115] the Konoe edition at Yōmei Bunko is a beautiful example of karakami[nb 14] with five-colored design (saisen);[116] and the Ōtagire is written on dyed paper decorated with gold drawings.[117][118]

The Konjaku Monogatarishū from ca. 1120 is the most important setsuwa compilation.[119][120] It is an anonymous collection of more than 1,000 anecdotes or tales.[121][122] About two-thirds of the tales are Buddhist, telling about the spread of Buddhism from India via China to Japan.[119][121] As such it is the first world history of Buddhism written in Japanese.[121] This National Treasure is also known as the Suzuka Manuscript and consists of nine volumes[nb 15] covering setsuwa from India (vols. 2 and 5), China (vols. 7, 9, 10) and Japan (vols. 12, 17, 27, 29).[4][121] It is considered to be the oldest extant manuscript of the Konjaku Monogatarishū and has served as a source for various later manuscripts.[123][124]

A commentary on the Genji Monogatari by Fujiwara no Teika, known as Okuiri ("Inside Notes" or "Endnotes") has been designated as a National Treasure.[125][126] Written around 1233 it is the second oldest Genji commentary, supplementing the oldest commentary, the Genji Shaku from 1160.[125][127][128]

| Name | Authors | Remarks | Date | Format | Present location | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nihon Ryōiki (日本霊異記) vol. 2, 3 | unknown | Japan's oldest collection of Buddhist setsuwa. Until its discovery in 1973 there was no complete text of the Nihon Ryōiki. A copy of the first volume housed at Kōfuku-ji, Nara is also a National Treasure. | late Heian period, 12th century | Two bound books (vol. 2, 3), ink on paper | Raigō-in (来迎院), Kyoto |  |

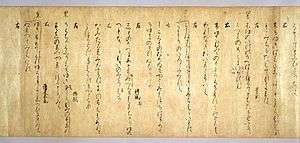

| Nihon Ryōiki (日本霊異記) vol. 1[129] | unknown | Japan's oldest collection of Buddhist setsuwa. A copy of the second volume housed at Raigō-in (来迎院), Kyoto is also a National Treasure. | Heian period, 904 | One handscroll (17 pages), ink on paper, 29.6 cm × 870 cm (11.7 in × 342.5 in) | Kōfuku-ji, Nara, Nara |  |

| Tosa Diary (土左日記 tosa no nikki)[130] | transcription by Fujiwara no Tameie | Faithful transcription of the 10th century original by Ki no Tsurayuki | Kamakura period, 1236 | One bound book, ink on paper, 16.8 cm × 15.3 cm (6.6 in × 6.0 in), 50 pages | Osaka Aoyama Junior College (大阪青山学園 Ōsaka Aoyama gakuen), Minoh, Osaka |  |

| Tosa Diary (土佐日記 tosa nikki) | transcription by Fujiwara no Teika | Faithful transcription of the 10th century original by Ki no Tsurayuki | Kamakura period, 1235 | One bound book, ink on paper | Maeda Ikutokukai, Tokyo | |

| Illustration of the Three Jewels (三宝絵詞 Sanbō Ekotoba)[131][132] | unknown | Illustrated interpretation of the three important concepts of Buddhism: Buddha, Dharma, Sangha; copy of an original by Minamoto no Tamenori (源為憲) (? – 1011) | Kamakura period, 1273 | Three books, ink on paper, 27.5 cm × 16.7 cm (10.8 in × 6.6 in) | Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo |  |

| Wakan rōeishū in ashide-e technique (芦手絵和漢朗詠抄 ashide-e wakan rōeishō)[118][133] | Fujiwara no Koreyuki (藤原伊行) | Combination of script and decorative motifs (ashide-e technique): reeds, water fowl, flying birds, rocks and wheels, in navy blue, greenish-blue, brownish-red and silver | late Heian period, 1160 | Two handscrolls, ink on paper, 27.9 cm × 367.9 cm (11.0 in × 144.8 in) and 27.9 cm × 422.9 cm (11.0 in × 166.5 in) | Kyoto National Museum, Kyoto |

|

| Wakanshō, second volume (倭漢抄下巻 wakanshō gekan), Konoe edition[134] | attributed to Fujiwara no Yukinari | Written on paper imprinted with motifs of plants, tortoise shells and phoenix in mica | Heian period, 11th century | Two handscrolls, ink on decorative paper with five-colored design (彩牋 saisen) | Yōmei Bunko, Kyoto |  |

| Wakan rōeishū (倭漢朗詠抄 wakan rōeishō), fragments of second volume or Ōtagire (太田切)[135][136] | attributed to Fujiwara no Yukinari | Handed down in the Ōta clan, daimyos of the Kakegawa Domain | Heian period, early 11th century | Two handscrolls, ink on decorated paper (gold drawings on paper printed and dyed), height: 25.7 cm (10.1 in), lengths: 337.3 cm (132.8 in) and 274.4 cm (108.0 in) | Seikadō Bunko Art Museum, Tokyo |  |

| Anthology of Tales from the Past (今昔物語集 Konjaku Monogatarishū)[137] | unknown | Collection of tales | late Heian period | Nine books bound by fukuro-toji[nb 3] (vol. 2, 5, 7, 9, 10, 12, 17, 27, 29) | Kyoto University, Kyoto |  |

| Commentary on The Tale of Genji (源氏物語奥入 Genji Monogatari okuiri) | Fujiwara no Teika | Oldest extant commentary on The Tale of Genji | Kamakura period, c. 1233 | One handscroll, ink on paper | private, Kyoto | .jpg) |

History books and historical tales

The oldest known[nb 16] Japanese[nb 17] large-scale works are historical books (Kojiki and Nihon Shoki) or regional cultural and geographical records (fudoki) compiled on imperial order in the early 8th century.[138][139][140] They were written with the aim of legitimizing the new centralized state under imperial rule by linking the origin of emperors to the Age of the Gods.[138][141][142] The oldest of these historical books is the Kojiki ("Record of ancient matters") dating from 712 and composed by Ō no Yasumaro at the request of Empress Gemmei.[9][143][144] Written in ancient Japanese style using Chinese ideographs, it presents the mythological origin of Japan and historical events up to the year 628.[143][144] Shortly after the completion of the Kojiki, the Nihon Shoki (or Nihongi) appeared in 720, probably originating to an order by Emperor Tenmu in 681.[140][145] It is a much more detailed version of the Kojiki, dating events and providing alternative versions of myths; it covers the time up to 697.[144][146][147] Compared to the Kojiki, it follows the model of Chinese dynastic histories more closely in style and language, using orthodox classical Chinese.[148][149] Both of these works provide the historical and spiritual basis for shinto.[144][150]

In 713, Empress Gemmei ordered provincial governors to compile official reports on the history, geography and local folk customs.[151][152][153] These provincial gazetteers are known as fudoki (lit. "Records of wind and earth") and provide valuable information about economic and ethnographic data, local culture and tales.[153][154] Of more than 60 provincial records compiled in the early 8th century only five survived: one, the Izumo Fudoki (733), in complete form and four, Bungo (730s), Harima (circa 715), Hitachi (714–718) and Hizen (730s) as fragments.[151][152][154] The Nihon Shoki is the first official history of Japan and the first of a set of six national histories (Rikkokushi) compiled over a 200-year period on Chinese models.[145][155][156] Based on these six histories, Sugawara no Michizane arranged historical events chronologically and thematically in the Ruijū Kokushi which was completed in 892.[157][158]

With the cessation of official missions to China and a general trend of turning away from Chinese-derived institutions and behavioral patterns in the latter part of the 9th century, the compilation of such national histories patterned on formal Chinese dynastic histories was abandoned.[159] With the development of kana script, new styles of uniquely Japanese literature such as the monogatari appeared around that time.[159] The newer style of historic writing that emerged during the Fujiwara regency, at the turning point of ancient imperial rule and the classical era, was called historic tale (rekishi monogatari) and became influenced by the fictional tale, especially by the Tale of Genji, with which it shared the scene-by-scene construction as fundamental difference to earlier historic writings.[nb 18][159][160][161] The oldest historical tale is the Eiga Monogatari ("A Tale of Flowering Fortunes"), giving a eulogistic chronological account of the Fujiwara from 946 to 1027, focusing particularly on Fujiwara Michinaga.[162][163][164] It was largely[nb 19] written by Akazome Emon, probably shortly after the death of Michinaga in 1027.[161][165]

There are eleven National Treasures in the category of historical books including one manuscript of the Kojiki, five manuscripts of the Nihon Shoki, the Harima and Hizen Fudoki, two manuscripts of the Ruijū Kokushi and one of the Eiga Monogatari. All of these treasures are later copies and with the exception of the Eiga Monogatari, the complete content of the works has to be assembled from several of these (and other) fragmentary manuscripts or be inferred from other sources. The Kojiki, long neglected by scholars until the 18th century, was not preserved as well as the Nihon Shoki which has been studied from soon after its compilation. While being the oldest text in this list, the extant manuscript dating to the 14th century is the earliest entry.[4][143]

| Name | Authors | Remarks | Date | Format | Present location | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Records of Ancient Matters (古事記 Kojiki), Shinpukuji manuscript (真福寺本) | transcription by the monk Ken'yu (賢瑜) | Oldest extant manuscript of the Kojiki | Nanboku-chō period, 1371–1372 | Three bound books | Ōsukannon (大須観音) Hōshō-in (宝生院), Nagoya, Aichi |  |

| The Chronicles of Japan (日本書紀 Nihon Shoki), Maeda edition | unknown | Part of the six national histories (Rikkokushi); handed down in the Maeda clan | Heian period, 11th century | Four handscrolls (volumes 11, 14, 17, 20), ink on paper | Maeda Ikutokukai, Tokyo |  |

| The Chronicles of Japan (日本書紀 Nihon Shoki), Iwasaki edition[166] | unknown | Part of the six national histories (Rikkokushi); handed down in the Iwasaki family | Heian period, around 1100 | Two handscrolls (volumes 22, 24: "Emperor Suiko", "Emperor Jomei"), ink on paper | Kyoto National Museum, Kyoto |  |

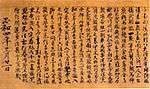

| Age of the Gods, chapters from The Chronicles of Japan (日本書紀神代巻 Nihon Shoki jindai-kan), Yoshida edition[167] | Urabe Kanekata (卜部兼方) | With a postscript by Urabe Kanekata; handed down in the Yoshida branch of the Urabe family; part of the six national histories (Rikkokushi) | Kamakura period, 1286 | Two handscrolls (volumes 1, 2), ink on paper, 29.7 cm × 3,012 cm (11.7 in × 1,185.8 in) and 30.3 cm × 3,386 cm (11.9 in × 1,333.1 in) | Kyoto National Museum, Kyoto | .jpg) |

| Age of the Gods, chapters from The Chronicles of Japan (日本書紀神代巻 Nihon Shoki jindai-kan), Yoshida edition | transcription and postscript by Urabe Kanekata (卜部兼方) | Handed down in the Yoshida branch of the Urabe family; part of the six national histories (Rikkokushi) | Kamakura period, 1303 | Two handscrolls (volumes 1, 2), ink on paper, 29 cm × 2,550 cm (11 in × 1,004 in) and 29 cm × 2,311 cm (11 in × 910 in) | Tenri University Library (天理大学附属天理図書館 Tenri daigaku fuzoku Tenri toshokan), Tenri, Nara |  |

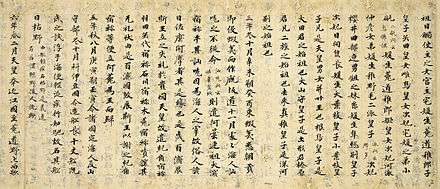

| The Chronicles of Japan (日本書紀 Nihon Shoki), Tanaka edition[168][169] | unknown | Oldest extant transcription of The Chronicles of Japan; considered to be stylistically close to the original from 720; contains a copy of the Collected Writings of Kūkai from the late Heian period on the back | Heian period, 9th century | Fragments (nine out of eleven sheets, first and last page missing) of one handscroll (vol. 10: "Emperor Ōjin"), ink on paper, 28.0 cm × 566.0 cm (11.0 in × 222.8 in) | Nara National Museum, Nara, Nara |  |

| Fudoki of Harima Province (播磨国風土記 Harima no kuni fudoki)[170] | unknown | Transcription of an ancient record of culture and geography from the early Nara period; oldest extant fudoki manuscript | end of Heian period | One handscroll, ink on paper, 28.0 cm × 886.0 cm (11.0 in × 348.8 in) | Tenri University Library (天理大学附属天理図書館 Tenri daigaku fuzoku Tenri toshokan), Tenri, Nara |  |

| Fudoki of Hizen Province (肥前国風土記 Hizen no kuni fudoki)[170] | unknown | Transcription of an ancient record of culture and geography from the early Nara period | Kamakura period | One bound book | Owner: private; Custody of: Kagawa Museum (香川県歴史博物館 Kagawa-ken Rekishi Hakubutsukan), Takamatsu, Kagawa Prefecture |  |

| Ruijū Kokushi (類聚国史)[171] | unknown | Collected by Maeda Tsunanori; one of the oldest extant manuscript of the Ruijū Kokushi | Heian period, 12th century | Four handscrolls (volumes 165, 171, 177, 179), ink on paper | Maeda Ikutokukai, Tokyo |  |

| Ruijū Kokushi (類聚国史)[172][173] | unknown | Formerly in the possession of Kanō Kōkichi (狩野亨吉), a doctor of literature at the Kyoto Imperial University; one of the oldest extant manuscript of the Ruijū Kokushi | late Heian period | One handscroll (vol. 25), 27.9 cm × 159.4 cm (11.0 in × 62.8 in) | Tohoku University, Sendai, Miyagi |  |

| Eiga Monogatari (栄花物語)[174][175] | unknown | Epic about the life of the courtier Fujiwara no Michinaga; oldest extant manuscript; handed down in the Sanjōnishi family | Kamakura period (Ōgata: mid-Kamakura, Masugata: early Kamakura) | 17 bound books: 10 from the Ōgata edition (until scroll 20), 7 from the Masugata edition (until scroll 40), ink on paper, 30.6 cm × 24.2 cm (12.0 in × 9.5 in) (Ōgata) and 16.3 cm × 14.9 cm (6.4 in × 5.9 in) (Masugata) | Kyushu National Museum, Dazaifu, Fukuoka |  |

Others

There are 18 Japanese book National Treasures that do not belong to any of the above categories. They cover 14 works of various types, including biographies, law or rulebooks, temple records, music scores, a medical book and dictionaries.[4] Two of the oldest works designated are biographies of the Asuka period regent Shōtoku Taishi. The Shitennō-ji Engi, alleged to have been an autobiography by Prince Shōtoku, described Shitennō-ji, and may have been created to promote the temple.[176] The Shitennō-ji Engi National Treasure consists of two manuscripts: the alleged original discovered in 1007 at Shitennō-ji and a later transcription by Emperor Go-Daigo.[176] Written by imperial order in the early 8th century, the Jōgū Shōtoku Hōō Teisetsu is the oldest extant biography of Shōtoku.[177][178][179] It consists of a collection of anecdotes, legendary and miraculous in nature, which emphasize Shōtoku's Buddhist activities for the sake of imperial legitimacy, and stands at the beginning of Buddhist setsuwa literature.[177][179] The oldest extant manuscript of the 803 Enryaku Kōtaishiki, a compendium of rules concerned with the change of provincial governors from 782 to 803, has been designated as a National Treasure.[180]

The oldest extant Japanese lexica date to the early Heian period.[181] Based on the Chinese Yupian, the Tenrei Banshō Meigi was compiled around 830 by Kūkai and is the oldest extant character dictionary made in Japan.[182][183] The Hifuryaku is a massive Chinese dictionary in 1000 fascicles listing the usage of words and characters in more than 1500 texts of diverse genres.[184] Compiled in 831 by Shigeno Sadanushi and others, it is the oldest extant Japanese proto-encyclopedia.[181][184] There are two National Treasures of the Ishinpō, the oldest extant medical treatise of Japanese authorship compiled in 984 by Tanba Yasuyori.[185][186][187] It is based on a large number of Chinese medical and pharmaceutical texts and contains knowledge about drug prescription, herbal lore, hygiene, acupuncture, moxibustion, alchemy and magic.[185] The two associated treasures consist of the oldest extant (partial) and the oldest extant complete manuscript respectively.[186][187]

Compiled between 905 and 927 by Tadahira, the Engishiki is the most respected legal compendium of the ritsuryō age and an important resource for the study of the Heian period court system.[188][189][190] Emperor Daigo commanded its compilation; the Engishiki is according to David Lu an "invaluable" resource and "one of the greatest compilations of laws and precedents".[189][190] The three designated National Treasures of the Engishiki represent the oldest extant manuscript (Kujō edition) and the oldest extant edition of certain date (Kongōji edition).[191] Two National Treasure manuscripts are related to music: the oldest extant kagura song book (Kagura wagon hifu) from around the 10th century and the oldest extant Saibara score (Saibara fu) which is traditionally attributed to Prince Munetaka but based on the calligraphy it appears to date to the mid-11th century.[192][193] The Hokuzanshō consists of writings by Fujiwara no Kintō on court customs and the function of the Daijō-kan. The designated Kyoto National Museum manuscript of the Hokuzanshō from about 1000 is noted for one of the few early extant examples of hiragana use and for the oldest extant letters in kana written on the reverse side of the scroll.[194][195] Around the early 12th century a Shingon Buddhist priest compiled a dictionary with a large number of variant form characters known as Ruiju Myōgishō. The designated Kanchiin edition is the oldest extant complete manuscript of this work.[196][197] Among the youngest items in this list are two temple records: the Omuro Sōjōki giving an account of priests of imperial lineage at Ninna-ji starting from the Kanpyō era, while the 1352 Tōhōki records treasures held at Tō-ji.[198][199][200] Kōbō Daishi's biography in an original manuscript penned by Emperor Go-Uda in 1315 has been designated as a National Treasure.[201]

| Name | Authors | Remarks | Date | Format | Present location | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Legendary history of Shitennō-ji (四天王寺縁起 Shitennō-ji engi)[176] | Prince Shōtoku (?) and Emperor Go-Daigo (transcription) | Document on the origin of Shitennō-ji and transcription | Heian period and Nanboku-chō period, 1335 | Two scrolls | Shitennō-ji, Osaka |  |

| Anecdotes of the sovereign dharma King Shōtoku of the Upper Palace (上宮聖徳法王帝説 Jōgū Shōtoku Hōō Teisetsu)[202] | unknown | Biography of Shōtoku Taishi | Heian period, 1050 (parts written by early 8th century) | One scroll, ink on paper, 26.7 cm × 228.8 cm (10.5 in × 90.1 in) | Chion-in, Kyoto |  |

| Enryaku regulations on the transfer of office (延暦交替式 Enryaku Kōtaishiki)[180] | unknown | Oldest extant copy of the original from 803 | Heian period, around 859–877 | One scroll, ink on paper | Ishiyama-dera, Ōtsu, Shiga |  |

| The myriad things, pronounced, defined, in seal script and clerical script (篆隷万象名義 Tenrei Banshō Meigi)[183] | unknown | Oldest extant Kanji dictionary. Transcription of the original by Kūkai from around 830–835 | Heian period, 1114 | Six bound books by fukuro-toji,[nb 3] ink on paper, 26.8 cm × 14.6 cm (10.6 in × 5.7 in) | Kōzan-ji, Kyoto |  |

| Hifuryaku (秘府略) | unknown | Part of the 1000 scrolls Hifuryaku, the oldest Japanese proto-encyclopedia from 831 | Heian period | One scroll, ink on paper: vol. 868 | Maeda Ikutokukai, Tokyo |  |

| Ishinpō (医心方), Nakarai edition[187][203] | unknown | Handed down in the Nakarai family; oldest extant transcription of this work | Heian period, 12th century[nb 20] | 30 scrolls, one bound book by fukuro-toji,[nb 3] ink on paper. Scroll 1: 27.7 cm × 248.0 cm (10.9 in × 97.6 in) | Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo |  |

| Ishinpō (医心方)[186] | unknown | Thought to be closer to the original as it contains fewer annotations than the Nakarai edition of the Ishinpō | Heian period | Five bound books, volumes 1, 5, 7, 9, fragments of 10 | Ninna-ji, Kyoto |  |

| Rules and regulations concerning ceremonies and other events (延喜式 Engishiki), Kujō edition[204][205] | unknown (more than one person) | Handed down in the Kujō family; the reverse side of 23 of these scrolls contain about 190 letters; oldest extant and most complete copy of Engishiki | Heian period, 11th century | 27 scrolls, ink on paper; vol. 2: 27.5 cm × 825.4 cm (10.8 in × 325.0 in), vol. 39: 28.7 cm × 1,080.2 cm (11.3 in × 425.3 in), vol. 42: 33.6 cm × 575.1 cm (13.2 in × 226.4 in) | Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo |  |

| Rules and regulations concerning ceremonies and other events (延喜式 Engishiki) Kongōji edition[191][206] | unknown | Oldest extant Engishiki manuscript of certain date | Heian period, 1127 | Three scrolls, ink on paper: vol. 12 fragments, vol. 14, vol. 16 | Kongō-ji (金剛寺), Kawachinagano, Osaka |  |

| Register of Shrines in Japan (延喜式神名帳 Engishiki Jinmyōchō)[207] | unknown | Volumes 9 and 10 of the Engishiki contain a register of Shinto shrines | Heian period, 1127 | One scroll, ink on paper: vol. 9 and 10 | Kongō-ji (金剛寺), Kawachinagano, Osaka |  |

| Secret kagura music for the six-stringed zither (神楽和琴秘譜 Kagura wagon hifu)[208] | attributed to Fujiwara no Michinaga | Oldest extant kagura song book | Heian period, 10th–11th century | One handscroll, ink on paper, 28.5 cm × 398.4 cm (11.2 in × 156.9 in) | Yōmei Bunko, Kyoto |  |

| Manual on Courtly Etiquette (北山抄 Hokuzanshō) | unknown | Transcription of the early 11th century original by Fujiwara no Kintō | Heian period | Twelve scrolls | Maeda Ikutokukai, Tokyo | |

| Manual on Courtly Etiquette, Volume 10 (稿本北山抄 kōhon Hokuzanshō)[195] | Fujiwara no Kintō | Draft to the Manual on Courtly Etiquette. Only extant volume of the original work in the author's own handwriting and oldest extant letters (on reverse side) in kana. Volume title: Guidance on Court Service. The paper used was taken from old letters and official documents. | Heian period, early 11th century, before 1012 | One handscroll, ink on paper, 30.3 cm × 1,279.0 cm (11.9 in × 503.5 in) | Kyoto National Museum, Kyoto |  |

| Saibara Music Score (催馬楽譜 Saibara fu)[192][193] | attributed to Prince Munetaka | Oldest extant Saibara score | Heian period, mid 11th century | One bound book by fukuro-toji,[nb 3] ink on paper with flying cloud design, 25.5 cm × 16.7 cm (10.0 in × 6.6 in) | Nabeshima Hōkōkai (鍋島報效会), Saga, Saga |  |

| Classified dictionary of pronunciations and meanings, annotated (類聚名義抄 Ruiju Myōgishō), Kanchi-in edition | unknown | Oldest extant complete edition; expanded and revised edition of the 11th century original | mid-Kamakura period | Eleven bound books | Tenri University Library (天理大学附属天理図書館 Tenri daigaku fuzoku Tenri toshokan), Tenri, Nara |  |

| Omuro sōjōki (御室相承記)[198][199] | unknown | — |

early Kamakura period | Six scrolls | Ninna-ji, Kyoto | .jpg) |

| Go-Uda tennō shinkan Kōbō Daishi den (後宇多天皇宸翰弘法大師伝)[201] | Emperor Go-Uda | Biography of Kōbō-Daishi (Kūkai), original manuscript | Kamakura period, March 21, 1315 | One hanging scroll, ink on silk, 37.3 cm × 123.6 cm (14.7 in × 48.7 in) | Daikaku-ji, Kyoto |  |

| History of Tō-ji (東宝記 Tōhōki) | edited by Gōhō (杲宝) and Kenpō (賢宝) | Record of treasures at Tō-ji | Nanboku-chō period to Muromachi period | Twelve scrolls, one bound book by fukuro-toji[nb 3] | Tō-ji, Kyoto |  |

See also

- Nara Research Institute for Cultural Properties

- Tokyo Research Institute for Cultural Properties

- Independent Administrative Institution National Museum

Notes

- ↑ Korea and China.

- ↑ Only the oldest period is counted, if a National Treasure consists of items from more than one period.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 (袋とじ) binding folded uncut pages in a book, so that there are two blank pages between two pages outside.

- ↑ Traces of ancient poems of courtship and praise for the ruler survive in the Kojiki, Nihon Shoki and Man'yōshū.

- ↑ The Man'yōshū also consists of a small amount of Chinese poetry (kanshi) and prose (kanbun).

- ↑ The manuscript calligraphy is attributable to Fujiwara no Tadaie -- see Tokyo National Museum, "Courtly Art: Heian to Muromachi Periods (8c-16c)," 2007; curatorial note by Kohitsu Ryōsa (1572–1662) at the end of the scroll -- see National Institutes for Cultural Heritage, "Essay on Ten Styles of Japanese Poems" retrieved 2011-07-26.

- ↑ As opposed to a publicly recognized and certified priest ordained by the ritsuryō state.

- ↑ They are the so called Kōfuku-ji and Shinpuku-ji manuscripts covering the first volume and the second to third volume respectively.

- ↑ The other two manuscripts are the Maeda (vol. 3) and Kōya (fragments of vols. 1 to 3) manuscripts.

- ↑ Poetry is used to express personal feelings.

- ↑ Tameie's transcription contains fewer mistakes than Teika's.

- ↑ Named after the Kanchiin subtemple of Tō-ji.

- ↑ A decorative pictorialized style of calligraphy in which characters are disguised in the shape of reeds (ashi), streams, rocks, flowers, birds, etc.

- ↑ An earth-colored based paper imported from China.

- ↑ Originally the Konjaku Monogatarishū consisted of 31 volumes of which 28 volumes remain today.

- ↑ Older texts such as the Tennōki, Kokki, Kyūji or Teiki from the 7th century have been lost, while others such as the Sangyō Gisho or the Taihō Code are relatively short or only exist as fragments.

- ↑ Composed in Japan on Japanese topics; most notably, the Japanese language is not meant here.

- ↑ Other differences are: a realistic dialogue, the presentation of more than one viewpoint and the embellishment with a wealth of realistic detail.

- ↑ 30 out of 40 volumes.

- ↑ 27 scrolls from Heian period, one scroll from Kamakura period, two scrolls and one bound manuscript added in Edo period.

References

- ↑ Coaldrake, William Howard (2002) [1996]. Architecture and authority in Japan. London, New York: Routledge. p. 248. ISBN 0-415-05754-X. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- ↑ Enders & Gutschow 1998, p. 12

- ↑ "Cultural Properties for Future Generations" (PDF). Tokyo, Japan: Agency for Cultural Affairs, Cultural Properties Department. March 2011. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 国指定文化財 データベース [Database of National Cultural Properties] (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. 2008-11-01. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- ↑ Seeley 1991, p. 25

- 1 2 Kornicki 1998, p. 93

- ↑ Brown & Hall 1993, p. 454

- ↑ Totman 2000, p. 114

- 1 2 3 Seeley 1991, p. 41

- ↑ Seeley 1991, p. 40

- ↑ Seeley 1991, p. 6

- ↑ Keally, Charles T. (2009-06-14). "Historic Archaeological Periods in Japan". Japanese Archaeology. Charles T. Keally. Retrieved 2010-09-09.

- ↑ Katō & Sanderson 1997, p. 12

- 1 2 Brown & Hall 1993, p. 459

- ↑ Brown & Hall 1993, p. 471

- 1 2 Brown & Hall 1993, pp. 460, 472–473

- ↑ Aston 2001, pp. 33–35

- ↑ Kodansha International 2004, p. 119

- 1 2 Brown & Hall 1993, pp. 460–461

- 1 2 3 Brown & Hall 1993, p. 475

- 1 2 Mason & Caiger 1997, p. 81

- 1 2 Kodansha International 2004, p. 120

- ↑ Shirane 2008b, pp. 2, 113–114

- 1 2 3 Frédéric 2005, p. 594

- ↑ Keene 1955, p. 23

- 1 2 Shively & McCullough 1999, pp. 432–433

- ↑ Aston 2001, p. 54

- 1 2 Shirane 2008b, p. 114

- ↑ Shively & McCullough 1999, p. 444

- ↑ McCullough 1991, p. 7

- ↑ McCullough 1991, p. 8

- ↑ Shirane 2008b, p. 116

- 1 2 Frédéric 2005, p. 595

- 1 2 3 4 Shirane 2008b, p. 571

- 1 2 Frédéric 2005, p. 1024

- ↑ Katō & Sanderson 1997, p. 2

- ↑ Shirane 2008b, p. 20

- ↑ Brown & Hall 1993, p. 466

- ↑ Brown & Hall 1993, p. 476

- ↑ Shirane 2008b, pp. 2, 6

- ↑ Carter 1993, p. 18

- ↑ Brown & Hall 1993, p. 473

- ↑ Shively & McCullough 1999, p. 431

- ↑ Carter 1993, p. 73

- 1 2 3 4 Shirane 2008b, p. 113

- ↑ Shively & McCullough 1999, p. 438

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Carter 1993, p. 74

- ↑ Shively & McCullough 1999, p. 433

- 1 2 Katō & Sanderson 1997, pp. 58–59

- 1 2 Shirane 2008b, p. 2

- ↑ Katō & Sanderson 1997, p. 58

- ↑ Shively & McCullough 1999, p. 432

- ↑ Katō & Sanderson 1997, p. 57

- ↑ Shirane 2008b, pp. 592–593

- 1 2 Shirane 2008b, p. 593

- ↑ Katō & Sanderson 1997, p. 59

- ↑ Shively & McCullough 1999, p. 436

- ↑ Carter 1993, p. 145

- ↑ Yamamura 1990, p. 453

- ↑ Carter 1993, pp. 145–146

- ↑ Addiss, Groemer & Rimer (eds.) 2006, p. 96

- ↑ Katō & Sanderson 1997, pp. 91–92

- ↑ Yamamura 1990, p. 454

- ↑ Carter 1993, p. 146

- ↑ Shirane 2008b, p. 572

- ↑ Deal 2007, p. 249

- ↑ Carter 1993, p. 147

- ↑ Deal 2007, p. 251

- ↑ 万葉集巻第九残巻 [Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves, fragments of scroll no. 9]. KNM Gallery (in Japanese). Kyoto National Museum. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

- ↑ "Fragment from the Ranshi Edition of Man'yoshu (Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves), Volume 9". Emuseum. Tokyo National Museum. 2004. Retrieved 2010-09-19.

- ↑ "Anthology of Ten Thousand Leaves, Genryaku Edition". Emuseum. Tokyo National Museum. 2004. Retrieved 2011-03-10.

- ↑ "古今和歌集 元永本" [Collected Japanese Poems of Ancient and Modern Times, Gen'ei edition]. Tokyo National Museum. Retrieved 2010-09-19.

- ↑ "古今和歌集 元永本" [Collected Japanese Poems of Ancient and Modern Times, Gen'ei edition]. Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved 2010-09-19.

- ↑ "Fragment from the Hon'ami Edition of Kokin Wakashu (Collection of Ancient and Modern Japanese Poems)". Emuseum. Tokyo National Museum. 2004. Retrieved 2010-09-19.

- ↑ 古今和歌集第十二残巻(本阿弥切本) [Fragment from the Hon'ami Edition of Kokin Wakashu (Collection of Ancient and Modern Japanese Poems)]. Cultural Heritage Online (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved 2009-07-03.

- ↑ 博物館概要・収蔵品一覧/毛利博物館 [Museum summary: Collection at a glance/Mōri Museum] (in Japanese). Retrieved 2009-07-03.

- ↑ 歌仙歌合 [Poetry Contest of Great Poets] (in Japanese). Tokugawa Art Museum. Retrieved 2011-06-15.

- ↑ "Poems from the Poetry Match Held by the Empress in the Kanpyō era". Emuseum. Tokyo National Museum. 2009. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ↑ 家祖 [Family founder]. The Reizei Family: Keepers of Classical Poetic Tradition (in Japanese). Asahi Shimbun. Retrieved 2011-05-20.

- ↑ "Essay on Ten Styles of Japanese Poems". Tokyo National Museum. 2011. Retrieved 2011-04-05.

- ↑ 三十六人家集 [Collection of 36 poets]. KNM Gallery (in Japanese). Nishi Hongan-ji. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ↑ 類聚古集 [Ruijūkoshū] (in Japanese). Ryukoku University. Retrieved 2009-07-04.

- ↑ "Ruijūkoshū". Ryukoku University Library. Retrieved 2009-07-04.

- ↑ 明恵上人歌集 [Collection of Poems by Priest Myōe]. KNM Gallery (in Japanese). Kyoto National Museum. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

- ↑ "Collection of Poems by Priest Myōe". Emuseum. Tokyo National Museum. 2004. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

- ↑ 前田家の名宝 [Famous Treasures of the Maeda Clan] (in Japanese). Ishikawa Prefectural Museum of Art. Retrieved 2011-05-20.

- 1 2 3 Shirane 2008b, p. 118

- 1 2 Shirane 2008b, p. 117

- 1 2 Keikai & Nakamura 1996, p. 3

- ↑ Keikai & Nakamura 1996, p. 33

- ↑ Keikai & Nakamura 1996, p. 9

- ↑ Tsurayuki & Porter 2005, pp. 5, 7

- ↑ Miner 1969, p. 20

- ↑ Frellesvig 2010, p. 175

- ↑ Tsurayuki & Porter 2005, p. 5

- ↑ Mason & Caiger 1997, p. 85

- ↑ Frédéric 2005, p. 516

- ↑ McCullough 1991, pp. 16, 70

- ↑ Varley 2000, p. 62

- ↑ Aston 2001, pp. 75–76

- 1 2 Kornicki 1998, p. 94

- ↑ Shively & McCullough 1999, p. 348

- ↑ Frédéric 2005, p. 815

- ↑ The work's title is variously translated as

- "Tale of the three brothers": Frédéric 2005, p. 815

- "The three jewels": Stone & Walter 2008, p. 105

- "Notes on the pictures of the three jewels": Iyengar 2006, p. 348

- ↑ Stone & Walter 2008, p. 105

- ↑ Groner 2002, p. 274

- ↑ Kamens & Minamoto 1988, p. 24

- ↑ Carter 1993, p. 125

- 1 2 Shirane 2008b, p. 286

- ↑ Smits, Ivo (2000). "Song as Cultural History: Reading Wakan Roeishu (Interpretations)". Monumenta Nipponica. 55 (3): 399–427. JSTOR 2668298.

- 1 2 Katō & Sanderson 1997, p. 61

- 1 2 Shirane 2008b, p. 285

- 1 2 Shively & McCullough 1999, p. 428

- ↑ Shirane 2008b, p. 287

- ↑ "Ashide". Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System. Retrieved 2011-05-04.

- ↑ "Karakami". Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System. Retrieved 2011-05-04.

- ↑ Nakata, Yūjirō (May 1973). The art of Japanese calligraphy. Weatherhill. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-8348-1013-6. Retrieved 2011-05-04.

- 1 2 "Wakan Roeishu Anthology". Kyoto National Museum. 2009. Retrieved 2009-07-01.

- 1 2 Totman 2000, p. 133

- ↑ Shively & McCullough 1999, p. 446

- 1 2 3 4 Shirane 2008b, p. 529

- ↑ Shively & McCullough 1999, p. 447

- ↑ 御挨拶 [Greeting]. 「今昔物語集」への招待 (Invitation to the Konjaku Monogatarishū) (in Japanese). Kyoto University. 1996. Retrieved 2011-05-02.

- ↑ Kelsey 1982, p. 14

- 1 2 Bowring 2004, p. 85

- ↑ Shirane 2008a, p. 24

- ↑ Caddeau 2006, p. 51

- ↑ Shirane 2008a, pp. 24, 138, 150

- ↑ "日本霊異記" [Nihon Ryōiki]. Kōfuku-ji. 2009. Retrieved 2010-09-17.

- ↑ "土左日記" [Tosa Diary]. Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved 2010-09-18.

- ↑ "Sanpo Ekotoba". Tokyo National Museum. 2009. Retrieved 2009-07-01.

- ↑ "Illustrated Tales of the Three Buddhist Jewels". Emuseum. Tokyo National Museum. Retrieved 2011-05-02.

- ↑ "Poems from Wakan Roeishu (Collection of Japanese and Chinese Verses) on Paper with Design of Reeds". Emuseum. Tokyo National Museum. Retrieved 2011-05-02.

- ↑ 陽明文庫創立70周年記念特別展「宮廷のみやび―近衞家1000年の名宝」 [Special Exhibition Courtly Millennium - Art Treasures from the Konoe Family Collection] (in Japanese). Tokyo National Museum. 2009. Retrieved 2010-09-18.

- ↑ 倭漢朗詠抄 [Wakan rōeishū] (in Japanese). Seikadō Bunko Art Museum. 2010. Retrieved 2011-04-15.

- ↑ "Wakan Roei-sho, known as Ota-gire". Seikadō Bunko Art Museum. 2010. Retrieved 2011-04-15.

- ↑ 今昔物語集への招待 [Invitation to the Anthology of Tales from the Past] (in Japanese). Kyoto University Library. Retrieved 2009-07-01.

- 1 2 Shirane 2008b, p. 1

- ↑ Brown & Hall 1993, pp. 470, 481

- 1 2 Sakamoto 1991, p. xi

- ↑ Brown & Hall 1993, p. 352

- ↑ Sakamoto 1991, p. xiii

- 1 2 3 Frédéric 2005, p. 545

- 1 2 3 4 Ono & Woodard 2004, p. 10

- 1 2 Shirane 2008b, p. 44

- ↑ Sakamoto 1991, pp. xi, xiv

- ↑ Seeley 1991, pp. 46–47

- ↑ Sakamoto 1991, p. xiv

- ↑ Breen & Teeuwen 2010, p. 29

- ↑ Brown & Hall 1993, p. 322

- 1 2 Brown & Hall 1993, p. 469

- 1 2 Frellesvig 2010, p. 25

- 1 2 Lewin 1994, p. 85

- 1 2 Shirane 2008b, p. 53

- ↑ Shirane 2008b, p. 45

- ↑ Varley 2000, pp. 67–68

- ↑ Burns 2003, p. 246

- ↑ Piggott 1997, p. 300

- 1 2 3 Varley 2000, p. 68

- ↑ Brownlee 1991, p. 42

- 1 2 Perkins 1998, p. 13

- ↑ McCullough 1991, pp. 11, 200

- ↑ Perkins 1998, pp. 13, 23

- ↑ Brownlee 1991, p. 46

- ↑ McCullough 1991, p. 11

- ↑ "The Iwasaki Edition of Nihon Shoki (Nihongi), Volumes 22 and 24". Emuseum. Tokyo National Museum. 2004. Retrieved 2010-09-17.

- ↑ "Postscript from the Yoshida Edition of Nihon Shoki (Nihongi)". Emuseum. Tokyo National Museum. 2004. Retrieved 2010-09-17.

- ↑ 日本書紀 [The Chronicles of Japan] (in Japanese). Nara National Museum. Retrieved 2010-09-17.

- ↑ "Chronicles of Japan, Volume 10". Emuseum. Tokyo National Museum. 2004. Retrieved 2009-07-01.

- 1 2 Shūhei, Aoki (2007-03-28). "Fudoki". Encyclopedia of Shinto (β1.3 ed.). Tokyo: Kokugakuin University. Retrieved 2010-09-17.

- ↑ 国宝 天神さま [The spirit of Sugawara no Michizane] (in Japanese). Kyushu National Museum. Retrieved 2010-09-17.

- ↑ 類聚国史 [Ruijū Kokushi] (in Japanese). Sendai, Miyagi. Retrieved 2010-09-17.

- ↑ 類聚国史 [Ruijū Kokushi] (in Japanese). Tohoku University. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

- ↑ 収蔵品ギャラリー『国宝・重要文化財』 [Gallery of collected items: National Treasures, Important Cultural Properties] (in Japanese). Kyushu National Museum. Retrieved 2010-09-17.

- ↑ 栄花物語 [Eiga Monogatari] (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved 2010-09-17.

- 1 2 3 Lee 2007, pp. 40–42

- 1 2 Lee 2007, p. 72

- ↑ Lee 2007, p. 141

- 1 2 Brown & Hall 1993, p. 482

- 1 2 延暦交替式 [Enryaku regulations on the transfer of office] (in Japanese). Otsu City Museum of History. Retrieved 2009-07-01.

- 1 2 Lewin 1994, p. 248

- ↑ Hausmann, Franz Josef (1991). Wörterbücher: ein internationales Handbuch zur Lexikographie. Walter de Gruyter. p. 2618. ISBN 978-3-11-012421-7. Retrieved 2011-05-15.

- 1 2 国宝 重要文化財 [National Treasures and Important Cultural Properties] (in Japanese). Kōzan-ji. Retrieved 2011-05-11.

- 1 2 Adolphson, Kamens & Matsumoto (eds.) 2007, p. 182

- 1 2 Leslie, Charles M. (1976). Asian medical systems: a comparative study. University of California Press. p. 327. ISBN 978-0-520-03511-9. Retrieved 2011-05-15.

- 1 2 3 , Ninna-ji edition"医心方" [Ishinpō]. Ninna-ji. Retrieved 2010-09-14.

- 1 2 3 "Prescriptions from the Heart of Medicine (Ishinpō)". Emuseum. Tokyo National Museum. Retrieved 2011-05-10.

- ↑ Totman 2000, p. 119

- 1 2 Lu, David John (1997). Japan: a documentary history. M.E. Sharpe. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-56324-906-8. Retrieved 2011-05-15.

- 1 2 Adolphson, Kamens & Matsumoto (eds.) 2007, p. 43

- 1 2 Seeley 1991, p. 55

- 1 2 "催馬楽譜" [Saibara Music Sheet]. Saga Prefecture. 2004. Retrieved 2009-07-01.

- 1 2 "催馬楽譜" [Saibara Music Sheet]. Nabeshima Hōkōkai. Retrieved 2011-05-12.

- ↑ Seeley 1991, p. 74

- 1 2 "Manual on Courtly Etiquette". Emuseum. Tokyo National Museum. 2004. Retrieved 2010-09-15.

- ↑ Kindaichi, Haruhiko; Hirano, Umeyo (1989-12-15). The Japanese language. Tuttle Publishing. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-8048-1579-6. Retrieved 2011-05-12.

- ↑ Seeley 1991, p. 126

- 1 2 "御室相承記" [Omuro sōjōki]. Nihon Kokugo Daijiten (in Japanese) (online ed.). Shogakukan. Retrieved 2011-05-16.

- 1 2 "御室相承記" [Omuro sōjōki]. Kokushi Daijiten (in Japanese) (online ed.). Yoshikawa Kobunkan. Retrieved 2011-05-16.

- ↑ Christine Guth Kanda (1985). Shinzō: Hachiman imagery and its development. Harvard Univ Asia Center. p. 54. ISBN 0-674-80650-6. Retrieved 2011-05-14.

- 1 2 後宇多天皇宸翰弘法大師伝 [Go-Uda tennō shinkan Kōbō Daishi den] (in Japanese). Daikaku-ji. Retrieved 2009-07-01.

- ↑ 上宮聖徳法王帝説 [Jōgū Shōtoku Hōō Teisetsu] (in Japanese). Chion-in. Retrieved 2010-09-12.

- ↑ "Ishinbo". Tokyo National Museum. Retrieved 2009-07-01.

- ↑ "Engishiki". Tokyo National Museum. Retrieved 2009-07-01.

- ↑ "Rule of the Engi era for the implementation of the penal code and administrative law". Emuseum. Tokyo National Museum. Retrieved 2011-05-10.

- ↑ "Engishiki". Kawachinagano, Osaka. Retrieved 2010-09-15.

- ↑ "Engishiki". Kawachinagano, Osaka. Retrieved 2010-09-15.

- ↑ Yōmei Bunko; Tokyo National Museum; NHK; NHK Promotion (2008). 宮廷のみやび: 近衛家1000年の名宝 : 陽明文庫創立70周年記念特別展 [Courtly Millennium - Art Treasures from the Konoe Family Collection]. NHK. p. 4.

Bibliography

- Addiss, Stephen; Groemer, Gerald; Rimer, J. Thomas, eds. (2006). Traditional Japanese Arts and Culture: An Illustrated Sourcebook. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2878-3. Retrieved 2011-06-12.

- Adolphson, Mikael S.; Kamens, Edward; Matsumoto, Stacie, eds. (2007). Heian Japan, Centers and Peripheries. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3013-7. Retrieved 2011-05-15.

- Aston, William George (2001). A History of Japanese Literature. Simon Publications LLC. ISBN 978-1-931313-94-0. Retrieved 2011-04-07.

- Bowring, Richard John (2004) [1988]. Murasaki Shikibu: the Tale of Genji (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-53975-3. Retrieved 2011-04-21.

- Breen, John; Teeuwen, Mark (2010). A New History of Shinto. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-1-4051-5515-1. Retrieved 2011-03-27.

- Brown, Delmer M.; Hall, John Whitney (1993). The Cambridge History of Japan: Ancient Japan. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-22352-2. Retrieved 2011-03-24.

- Brownlee, John S. (1991). Political Thought in Japanese Historical Writing: From Kojiki (712) to Tokushi Yoron (1712). Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press. ISBN 0-88920-997-9. Retrieved 2011-03-29.

- Burns, Susan L. (2003). Before the Nation: Kokugaku and the Imagining of Community in Early Modern Japan. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-3172-8. Retrieved 2011-03-24.

- Caddeau, Patrick W. (2006). Appraising Genji: Literary Criticism and Cultural Anxiety in the Age of the Last Samurai. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-6673-5. Retrieved 2011-04-28.

- Carter, Steven D. (1993). Traditional Japanese Poetry: An Anthology. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2212-4. Retrieved 2011-04-27.

- Deal, William E. (2007) [1973]. Handbook to Life in Medieval and Early Modern Japan (revised and illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-533126-5. Retrieved 2009-11-10.

- Enders, Siegfried R. C. T.; Gutschow, Niels (1998). Hozon: Architectural and Urban Conservation in Japan (illustrated ed.). Edition Axel Menges. ISBN 3-930698-98-6. Retrieved 2011-07-20.

- Frédéric, Louis (2005). Japan Encyclopedia (illustrated ed.). Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01753-6. Retrieved 2010-03-19.

- Frellesvig, Bjarke (2010). A History of the Japanese Language. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-65320-6. Retrieved 2011-03-22.

- Groner, Paul (2002). Ryōgen and Mount Hiei: Japanese Tendai in the Tenth Century. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2260-6. Retrieved 2011-04-17.

- Iyengar, Kodaganallur Ramaswami Srinivasa (2006). Asian Variations in Ramayana. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 978-81-260-1809-3. Retrieved 2011-04-17.

- Kamens, Edward; Minamoto, Tamenori (1988). The Three Jewels: A Study and Translation of Minamoto Tamenori's Sanbōe. Center for Japanese Studies, University of Michigan. ISBN 978-0-939512-34-8. Retrieved 2011-05-03.

- Katō, Shūichi; Sanderson, Don (1997). A History of Japanese Literature: From the Man'yōshū to Modern Times. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-1-873410-48-6. Retrieved 2011-04-06.

- Keene, Donald (1955). Anthology of Japanese Literature, from the Earliest Era to the Mid-nineteenth Century. Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-5058-5. Retrieved 2011-04-07.

- Keene, Donald (1993). The Pleasures of Japanese Literature. Columbia University Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-231-06737-9. Retrieved 2011-04-25.

- Keikai; Nakamura, Kyōko Motomochi (1996). Miraculous Stories from the Japanese Buddhist Tradition: he Nihon Ryōiki of the Monk Kyōkai (annotated and reprinted ed.). Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-7007-0449-1. Retrieved 2011-04-24.

- Kelsey, W. Michael (1982). Konjaku Monogatari-shū. Twayne Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8057-6463-5. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- The Japan Book: A Comprehensive Pocket Guide. Kodansha International. 2004. ISBN 978-4-7700-2847-1. Retrieved 2011-04-06.

- Kornicki, Peter Francis (1998). The Book in Japan: A Cultural History from the Beginnings to the Nineteenth Century. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-10195-1. Retrieved 2011-02-28.

- Lee, Kenneth Doo (2007). The Prince and the Monk: Shōtoku Worship in Shinran's Buddhism. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-7021-3. Retrieved 2011-05-13.

- Lewin, Bruno (1994). Kleines Lexikon der Japanologie: zur Kulturgeschichte Japans (in German). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-03668-9. Retrieved 2011-01-22.

- Mason, R. H. P.; Caiger, John Godwin (1997). A History of Japan. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8048-2097-4. Retrieved 2011-04-06.

- McCullough, Helen Craig (1991). Classical Japanese Prose: An Anthology. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-1960-5. Retrieved 2011-03-29.

- Miner, Earl (1969). Japanese Poetic Diaries. University of California Press. Retrieved 2011-04-25.

- Ono, Sokyo; Woodard, William P. (2004). Shinto the Kami Way. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8048-3557-2. Retrieved 2011-03-26.

- Perkins, George W. (1998). The Clear Mirror: a Chronicle of the Japanese Court During the Kamakura Period (1185-1333). Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2953-6. Retrieved 2011-03-29.

- Piggott, Joan R. (1997). The Emergence of Japanese Kingship. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2832-4. Retrieved 2011-03-24.

- Sakamoto, Tarō (1991). The Six National Histories of Japan. UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-0379-3. Retrieved 2011-03-27.

- Seeley, Christopher (1991). A History of Writing in Japan. Brill's Japanese studies library. 3 (illustrated ed.). BRILL. ISBN 90-04-09081-9. Retrieved 2011-07-20.

- Shirane, Haruo (2008a). Envisioning the Tale of Genji: Media, Gender, and Cultural Production. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-14237-3. Retrieved 2011-04-21.

- Shirane, Haruo (2008b). Traditional Japanese Literature: An Anthology, Beginnings to 1600. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13697-6. Retrieved 2011-03-24.

- Shively, Donald H.; McCullough, William H. (1999). The Cambridge History of Japan: Heian Japan. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-22353-9. Retrieved 2011-03-27.

- Stone, Jacqueline Ilyse; Walter, Mariko Namba (2008). Death and the Afterlife in Japanese Buddhism. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3204-9. Retrieved 2011-04-17.

- Totman, Conrad D. (2000). A History of Japan. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-21447-2. Retrieved 2011-04-22.

- Tsurayuki, Ki no; Porter, William N. (2005). The Tosa Diary. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8048-3695-1. Retrieved 2011-04-25.

- Varley, H. Paul (2000). Japanese Culture. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2152-4. Retrieved 2011-03-07.

- Yamamura, Kozo (1990). The Cambridge History of Japan: Medieval Japan. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-22354-6. Retrieved 2011-06-12.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to National Treasure writings. |